| Geometry |

|---|

|

| Geometers |

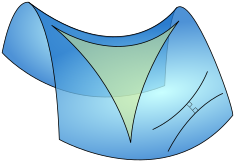

Differential geometry is a mathematical discipline that studies the geometry of smooth shapes and smooth spaces, otherwise known as smooth manifolds. It uses the techniques of differential calculus, integral calculus, linear algebra and multilinear algebra. The field has its origins in the study of spherical geometry as far back as antiquity. It also relates to astronomy, the geodesy of the Earth, and later the study of hyperbolic geometry by Lobachevsky. The simplest examples of smooth spaces are the plane and space curves and surfaces in the three-dimensional Euclidean space, and the study of these shapes formed the basis for development of modern differential geometry during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Since the late 19th century, differential geometry has grown into a field concerned more generally with geometric structures on differentiable manifolds. A geometric structure is one which defines some notion of size, distance, shape, volume, or other rigidifying structure. For example, in Riemannian geometry distances and angles are specified, in symplectic geometry volumes may be computed, in conformal geometry only angles are specified, and in gauge theory certain fields are given over the space. Differential geometry is closely related to, and is sometimes taken to include, differential topology, which concerns itself with properties of differentiable manifolds which do not rely on any additional geometric structure (see that article for more discussion on the distinction between the two subjects). Differential geometry is also related to the geometric aspects of the theory of differential equations, otherwise known as geometric analysis.

Differential geometry finds applications throughout mathematics and the natural sciences. Most prominently the language of differential geometry was used by Albert Einstein in his theory of general relativity, and subsequently by physicists in the development of quantum field theory and the standard model of particle physics. Outside of physics, differential geometry finds applications in chemistry, economics, engineering, control theory, computer graphics and computer vision, and recently in machine learning where it is hypothesized to be the correct language to explain the effectiveness of certain algorithms (in an approach known as geometric deep learning[1])..

History and development

editThe history and development of differential geometry as a subject begins at least as far back as classical antiquity. It is intimately linked to the development of geometry more generally, of the notion of space and shape, and of topology, especially the study of manifolds. In this section we focus primarily on the history of the application of infinitesimal methods to geometry, and later to the ideas of tangent spaces, and eventually the development of the modern formalism of the subject in terms of tensors and tensor fields.

Classical antiquity until the Renaissance (300 BC – 1600 AD)

editThe study of differential geometry, or at least the study of the geometry of smooth shapes, can be traced back at least to classical antiquity. In particular, much was known about the geometry of the Earth, a spherical geometry, in the time of the ancient Greek mathematicians. Famously, Eratosthenes calculated the circumference of the Earth around 200 BC, and around 150 AD Ptolemy in his Geography introduced the stereographic projection for the purposes of mapping the shape of the Earth.[2] Implicitly throughout this time principles that form the foundation of differential geometry and calculus were used in geodesy, although in a much simplified form. Namely, as far back as Euclid's Elements it was understood that a straight line could be defined by its property of providing the shortest distance between two points, and applying this same principle to the surface of the Earth leads to the conclusion that great circles, which are only locally similar to straight lines in a flat plane, provide the shortest path between two points on the Earth's surface. Indeed the measurements of distance along such geodesic paths by Eratosthenes and others can be considered a rudimentary measure of arclength of curves, a concept which did not see a rigorous definition in terms of calculus until the 1600s.

Around this time there were only minimal overt applications of the theory of infinitesimals to the study of geometry, a precursor to the modern calculus-based study of the subject. In Euclid's Elements the notion of tangency of a line to a circle is discussed, and Archimedes applied the method of exhaustion to compute the areas of smooth shapes such as the circle, and the volumes of smooth three-dimensional solids such as the sphere, cones, and cylinders.[2]

There was little development in the theory of differential geometry between antiquity and the beginning of the Renaissance. Before the development of calculus by Newton and Leibniz, the most significant development in the understanding of differential geometry came from Gerardus Mercator's development of the Mercator projection as a way of mapping the Earth. Mercator had an understanding of the advantages and pitfalls of his map design, and in particular was aware of the conformal nature of his projection, as well as the difference between praga, the lines of shortest distance on the Earth, and the directio, the straight line paths on his map. Mercator noted that the praga were oblique curvatur in this projection.[2] This fact reflects the lack of a metric-preserving map of the Earth's surface onto a flat plane, a consequence of the later Theorema Egregium of Gauss.

After calculus (1600–1800)

editThe first systematic or rigorous treatment of geometry using the theory of infinitesimals and notions from calculus began around the 1600s when calculus was first developed by Gottfried Leibniz and Isaac Newton. At this time, the recent work of René Descartes introducing analytic coordinates to geometry allowed geometric shapes of increasing complexity to be described rigorously. In particular around this time Pierre de Fermat, Newton, and Leibniz began the study of plane curves and the investigation of concepts such as points of inflection and circles of osculation, which aid in the measurement of curvature. Indeed already in his first paper on the foundations of calculus, Leibniz notes that the infinitesimal condition indicates the existence of an inflection point. Shortly after this time the Bernoulli brothers, Jacob and Johann made important early contributions to the use of infinitesimals to study geometry. In lectures by Johann Bernoulli at the time, later collated by L'Hopital into the first textbook on differential calculus, the tangents to plane curves of various types are computed using the condition , and similarly points of inflection are calculated.[2] At this same time the orthogonality between the osculating circles of a plane curve and the tangent directions is realised, and the first analytical formula for the radius of an osculating circle, essentially the first analytical formula for the notion of curvature, is written down.

In the wake of the development of analytic geometry and plane curves, Alexis Clairaut began the study of space curves at just the age of 16.[3][2] In his book Clairaut introduced the notion of tangent and subtangent directions to space curves in relation to the directions which lie along a surface on which the space curve lies. Thus Clairaut demonstrated an implicit understanding of the tangent space of a surface and studied this idea using calculus for the first time. Importantly Clairaut introduced the terminology of curvature and double curvature, essentially the notion of principal curvatures later studied by Gauss and others.

Around this same time, Leonhard Euler, originally a student of Johann Bernoulli, provided many significant contributions not just to the development of geometry, but to mathematics more broadly.[4] In regards to differential geometry, Euler studied the notion of a geodesic on a surface deriving the first analytical geodesic equation, and later introduced the first set of intrinsic coordinate systems on a surface, beginning the theory of intrinsic geometry upon which modern geometric ideas are based.[2] Around this time Euler's study of mechanics in the Mechanica lead to the realization that a mass traveling along a surface not under the effect of any force would traverse a geodesic path, an early precursor to the important foundational ideas of Einstein's general relativity. Euler also introduced the Euler–Lagrange equations and the first theory of the calculus of variations, which underpins in modern differential geometry many techniques in symplectic geometry and geometric analysis. This theory was used by Lagrange, a co-developer of the calculus of variations, to derive the first differential equation describing a minimal surface in terms of the Euler–Lagrange equation. In 1760 Euler proved a theorem expressing the curvature of a space curve on a surface in terms of the principal curvatures, known as Euler's theorem.

Later in the 1700s, the new French school lead by Gaspard Monge began to make contributions to differential geometry. Monge made important contributions to the theory of plane curves, surfaces, and studied surfaces of revolution and envelopes of plane curves and space curves. Several students of Monge made contributions to this same theory, and for example Charles Dupin provided a new interpretation of Euler's theorem in terms of the principle curvatures, which is the modern form of the equation.[2]

Intrinsic geometry and non-Euclidean geometry (1800–1900)

editThe field of differential geometry became an area of study considered in its own right, distinct from the more broad idea of analytic geometry, in the 1800s, primarily through the foundational work of Carl Friedrich Gauss and Bernhard Riemann, and also in the important contributions of Nikolai Lobachevsky on hyperbolic geometry and non-Euclidean geometry and throughout the same period the development of projective geometry.

Dubbed the single most important work in the history of differential geometry,[5] in 1827 Gauss produced the Disquisitiones generales circa superficies curvas detailing the general theory of curved surfaces.[6][5][7] In this work and his subsequent papers and unpublished notes on the theory of surfaces, Gauss has been dubbed the inventor of non-Euclidean geometry and the inventor of intrinsic differential geometry.[7] In his fundamental paper Gauss introduced the Gauss map, Gaussian curvature, first and second fundamental forms, proved the Theorema Egregium showing the intrinsic nature of the Gaussian curvature, and studied geodesics, computing the area of a geodesic triangle in various non-Euclidean geometries on surfaces.

At this time Gauss was already of the opinion that the standard paradigm of Euclidean geometry should be discarded, and was in possession of private manuscripts on non-Euclidean geometry which informed his study of geodesic triangles.[7][8] Around this same time János Bolyai and Lobachevsky independently discovered hyperbolic geometry and thus demonstrated the existence of consistent geometries outside Euclid's paradigm. Concrete models of hyperbolic geometry were produced by Eugenio Beltrami later in the 1860s, and Felix Klein coined the term non-Euclidean geometry in 1871, and through the Erlangen program put Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries on the same footing.[9] Implicitly, the spherical geometry of the Earth that had been studied since antiquity was a non-Euclidean geometry, an elliptic geometry.

The development of intrinsic differential geometry in the language of Gauss was spurred on by his student, Bernhard Riemann in his Habilitationsschrift, On the hypotheses which lie at the foundation of geometry.[10] In this work Riemann introduced the notion of a Riemannian metric and the Riemannian curvature tensor for the first time, and began the systematic study of differential geometry in higher dimensions. This intrinsic point of view in terms of the Riemannian metric, denoted by by Riemann, was the development of an idea of Gauss' about the linear element of a surface. At this time Riemann began to introduce the systematic use of linear algebra and multilinear algebra into the subject, making great use of the theory of quadratic forms in his investigation of metrics and curvature. At this time Riemann did not yet develop the modern notion of a manifold, as even the notion of a topological space had not been encountered, but he did propose that it might be possible to investigate or measure the properties of the metric of spacetime through the analysis of masses within spacetime, linking with the earlier observation of Euler that masses under the effect of no forces would travel along geodesics on surfaces, and predicting Einstein's fundamental observation of the equivalence principle a full 60 years before it appeared in the scientific literature.[7][5]

In the wake of Riemann's new description, the focus of techniques used to study differential geometry shifted from the ad hoc and extrinsic methods of the study of curves and surfaces to a more systematic approach in terms of tensor calculus and Klein's Erlangen program, and progress increased in the field. The notion of groups of transformations was developed by Sophus Lie and Jean Gaston Darboux, leading to important results in the theory of Lie groups and symplectic geometry. The notion of differential calculus on curved spaces was studied by Elwin Christoffel, who introduced the Christoffel symbols which describe the covariant derivative in 1868, and by others including Eugenio Beltrami who studied many analytic questions on manifolds.[11] In 1899 Luigi Bianchi produced his Lectures on differential geometry which studied differential geometry from Riemann's perspective, and a year later Tullio Levi-Civita and Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro produced their textbook systematically developing the theory of absolute differential calculus and tensor calculus.[12][5] It was in this language that differential geometry was used by Einstein in the development of general relativity and pseudo-Riemannian geometry.

Modern differential geometry (1900–2000)

editThe subject of modern differential geometry emerged out of the early 1900s in response to the foundational contributions of many mathematicians, including importantly the work of Henri Poincaré on the foundations of topology.[13] At the start of the 1900s there was a major movement within mathematics to formalise the foundational aspects of the subject to avoid crises of rigour and accuracy, known as Hilbert's program. As part of this broader movement, the notion of a topological space was distilled in by Felix Hausdorff in 1914, and by 1942 there were many different notions of manifold of a combinatorial and differential-geometric nature.[13]

Interest in the subject was also focused by the emergence of Einstein's theory of general relativity and the importance of the Einstein Field equations. Einstein's theory popularised the tensor calculus of Ricci and Levi-Civita and introduced the notation for a Riemannian metric, and for the Christoffel symbols, both coming from G in Gravitation. Élie Cartan helped reformulate the foundations of the differential geometry of smooth manifolds in terms of exterior calculus and the theory of moving frames, leading in the world of physics to Einstein–Cartan theory.[14][5]

Following this early development, many mathematicians contributed to the development of the modern theory, including Jean-Louis Koszul who introduced connections on vector bundles, Shiing-Shen Chern who introduced characteristic classes to the subject and began the study of complex manifolds, Sir William Vallance Douglas Hodge and Georges de Rham who expanded understanding of differential forms, Charles Ehresmann who introduced the theory fibre bundles and Ehresmann connections, and others.[14][5] Of particular important was Hermann Weyl who made important contributions to the foundations of general relativity, introduced the Weyl tensor providing insight into conformal geometry, and first defined the notion of a gauge leading to the development of gauge theory in physics and mathematics.

In the middle and late 20th century differential geometry as a subject expanded in scope and developed links to other areas of mathematics and physics. The development of gauge theory and Yang–Mills theory in physics brought bundles and connections into focus, leading to developments in gauge theory. Many analytical results were investigated including the proof of the Atiyah–Singer index theorem. The development of complex geometry was spurred on by parallel results in algebraic geometry, and results in the geometry and global analysis of complex manifolds were proven by Shing-Tung Yau and others. In the latter half of the 20th century new analytic techniques were developed in regards to curvature flows such as the Ricci flow, which culminated in Grigori Perelman's proof of the Poincaré conjecture. The development of geometric analysis at this time also lead to a deeper understanding of variational techniques harkening back to Euler and Lagrange's calculus of variations, and of harmonic maps. In particular work of F. Reese Harvey and H. Blaine Lawson as well as Karen Uhlenbeck set geometric analysis on a new footing and provided many tools which would become critically important in the proceeding decades, and for example provided deeper understanding of minimal submanifolds and calibrated geometry. During this same period primarily due to the influence of Michael Atiyah, new links between theoretical physics and differential geometry were formed. Techniques from the study of the Yang–Mills equations and gauge theory were used by mathematicians to develop new invariants of smooth manifolds. Physicists such as Edward Witten, the only physicist to be awarded a Fields medal, made new impacts in mathematics by using topological quantum field theory and string theory to make predictions and provide frameworks for new rigorous mathematics, which has resulted for example in the conjectural mirror symmetry and the Seiberg–Witten invariants.

Extrinsic and intrinsic perspectives

editFrom the beginning and through the middle of the 19th century, differential geometry was studied from the extrinsic point of view: curves and surfaces were considered as lying in a Euclidean space of higher dimension (for example a surface in an ambient space of three dimensions). The simplest results are those in the differential geometry of curves and differential geometry of surfaces. Beginning with the work of Euler on intrinsic coordinate systems, this extraneous assumption, that the geometric shape of interest must necessarily be embedded in some ambient space, began to be removed. In particular Gauss' Theorema Egregium showed that certain geometric properties of a shape can be deduced independently of which ambient space it is embedded inside, in particular the Gaussian curvature of a surface. This was explained by his student Riemann, who produced an invariant definition of geometry in the form of a Riemannian metric, a concept which does not need an ambient space to be defined, but still allows one to encode many basic geometric properties such as distance, area, volume, and curvature.

The subsequent developments in geometry and topology, as well as the notion of spacetime developed in general relativity, lead to a shift in focus, which is typified by the shift in terminology from shape to space in the 20th century to describe geometric objects of interest. This new intrinsic viewpoint is more flexible, and aligns closely with the formalisation of mathematics in light of Hilbert's program, but comes at the cost of a more sophisticated and complicated theory which does not obviously align with the visual intuition of curves and surfaces in low dimensions. Nevertheless these two points of view can be reconciled, i.e. the extrinsic geometry can be considered as a structure additional to the intrinsic one. (See the Nash embedding theorem.) In the formalism of geometric calculus both extrinsic and intrinsic geometry of a manifold can be characterized by a single bivector-valued one-form called the shape operator.[15]

Fundamental notions

editModern differential geometry, following the intrinsic approach, takes the perspective of beginning with a space, typically a topological manifold, and adding geometric structures to it. In order to apply techniques of differential and integral calculus, this manifold always comes with some kind of smooth structure, although allowing singularities of various kinds is often important (for example by studying orbifolds, manifolds with corners, or singular analytic varieties). Which geometric structure is added changes the properties of the manifold, and typically makes it "more rigid" in the sense that there are less degrees of freedom in varying that structure. Examples of such geometric structures and how they restrict degrees of freedom are the following:

- A smooth structure on a topological manifold, where every smooth diffeomorphism is also a homeomorphism.

- A Riemannian metric on a smooth manifold, where every isometry is also a diffeomorphism.

- A symplectic form on a smooth manifold, where every symplectomorphism is a diffeomorphism.

- A complex structure or algebraic structure, where every biholomorphism or algebraic isomorphism (also known as a biregular map) is a smooth, and even real analytic idffeomorphism.

Each geometric structure leads to a different branch of differential geometry, and a detailed list of such branches appears below.

The interactions between various geometric structures and the way that rigidity restricts or characterises the properties of the underlying space are major topics of interest in geometry. For example in low dimensions it actually manifests that smooth manifolds are no more rigid than topological manifolds, since two smooth manifolds of dimensions one, two, or three which are homeomorphic are actually diffeomorphic. This fails beginning in dimension four, where the Euclidean space admits uncountably many non-diffeomorphic smooth structures. Other circumstances where the extra rigidity of a smooth structure actually reduce to a more flexible setting are studied in differential topology where many geometric constructions reveal information about the topology of the underlying manifold.

The following are the most fundamental notions which appear in the study of differential geometry.

Manifolds

editDifferential geometry is studied, excepting few circumstances, on smooth manifolds. The notion of a smooth manifold was distilled in the early-mid 20th century as an appropriate space upon which techniques of calculus can be applied, especially the definition of the derivative and integral of a function. Manifolds enable this by looking locally similar to the standard Euclidean space where calculus is well-understood. Since differentiation only depends on local behavior of the function and the underlying space it is defined upon, and by the change of variables formula that integration is invariant under a diffeomorphism, if these local pieces of Euclidean space are glued using diffeomorphic maps then both the derivative and integral can be defined.

A smooth manifold consists of the following data: A topological space which is Hausdorff and paracompact (or second-countable, the two notions being equivalent for connected manifolds), such that:

- For every point there exists an open neighbourhood of and a homeomorphism (called a chart) onto an open subset of some Euclidean space.

- For any two overlapping charts and , on the intersection the transition function is a diffeomorphism of open subsets of .

A covering of M by charts with transition functions that are diffeomorphisms is called a smooth atlas or smooth structure. The number (which is independent of the chart, since it is preserved under diffeomorphism) is called the dimension of the smooth manifold. The study of smooth manifolds without any further geometric structure is known as differential topology.

Tangent vectors, tensors, and tensor fields

editThe smooth structure on a manifold allows certain infinitesimal constructions to be performed. Namely, just as the derivative of a smooth function represents the best linear approximation of that function at a point, a smooth manifold admits a linear approximation at each point , the tangent space consisting of tangent directions to the manifold at that point (note that "normal directions" cannot be defined as there is no ambient space in which the manifold sits). This vector space is isomorphic the local model Euclidean space where is the dimension of , and the derivative of a function at is naturally a linear functional on this space (a one-form), which takes as input a tangent direction and produces the derivative of the function along that direction.

Constructions from linear algebra and multilinear algebra can be transferred to the tangent space of a manifold at a point . In particular one may consider tensors at the point (typically a tensor on a manifold refers specifically to a tensor constructed out of the tangent bundle

Curvature

editTools and techniques

editVector bundles and principal bundles

editThe apparatus of vector bundles, principal bundles, and connections on bundles plays an extraordinarily important role in modern differential geometry. A smooth manifold always carries a natural vector bundle, the tangent bundle. Loosely speaking, this structure by itself is sufficient only for developing analysis on the manifold, while doing geometry requires, in addition, some way to relate the tangent spaces at different points, i.e. a notion of parallel transport. An important example is provided by affine connections. For a surface in R3, tangent planes at different points can be identified using a natural path-wise parallelism induced by the ambient Euclidean space, which has a well-known standard definition of metric and parallelism. In Riemannian geometry, the Levi-Civita connection serves a similar purpose. More generally, differential geometers consider spaces with a vector bundle and an arbitrary affine connection which is not defined in terms of a metric. In physics, the manifold may be spacetime and the bundles and connections are related to various physical fields.

Connections

editDifferential equations

editBranches

editRiemannian geometry

editRiemannian geometry studies Riemannian manifolds, smooth manifolds with a Riemannian metric. This is a concept of distance expressed by means of a smooth positive definite symmetric bilinear form defined on the tangent space at each point. Riemannian geometry generalizes Euclidean geometry to spaces that are not necessarily flat, though they still resemble Euclidean space at each point infinitesimally, i.e. in the first order of approximation. Various concepts based on length, such as the arc length of curves, area of plane regions, and volume of solids all possess natural analogues in Riemannian geometry. The notion of a directional derivative of a function from multivariable calculus is extended to the notion of a covariant derivative of a tensor. Many concepts of analysis and differential equations have been generalized to the setting of Riemannian manifolds.

A distance-preserving diffeomorphism between Riemannian manifolds is called an isometry. This notion can also be defined locally, i.e. for small neighborhoods of points. Any two regular curves are locally isometric. However, the Theorema Egregium of Carl Friedrich Gauss showed that for surfaces, the existence of a local isometry imposes that the Gaussian curvatures at the corresponding points must be the same. In higher dimensions, the Riemann curvature tensor is an important pointwise invariant associated with a Riemannian manifold that measures how close it is to being flat. An important class of Riemannian manifolds is the Riemannian symmetric spaces, whose curvature is not necessarily constant. These are the closest analogues to the "ordinary" plane and space considered in Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry.

Pseudo-Riemannian geometry

editPseudo-Riemannian geometry generalizes Riemannian geometry to the case in which the metric tensor need not be positive-definite. A special case of this is a Lorentzian manifold, which is the mathematical basis of Einstein's general relativity theory of gravity.

Finsler geometry

editFinsler geometry has Finsler manifolds as the main object of study. This is a differential manifold with a Finsler metric, that is, a Banach norm defined on each tangent space. Riemannian manifolds are special cases of the more general Finsler manifolds. A Finsler structure on a manifold M is a function F : TM → [0, ∞) such that:

- F(x, my) = m F(x, y) for all (x, y) in TM and all m≥0,

- F is infinitely differentiable in TM ∖ {0},

- The vertical Hessian of F2 is positive definite.

Symplectic geometry

editSymplectic geometry is the study of symplectic manifolds. An almost symplectic manifold is a differentiable manifold equipped with a smoothly varying non-degenerate skew-symmetric bilinear form on each tangent space, i.e., a nondegenerate 2-form ω, called the symplectic form. A symplectic manifold is an almost symplectic manifold for which the symplectic form ω is closed: dω = 0.

A diffeomorphism between two symplectic manifolds which preserves the symplectic form is called a symplectomorphism. Non-degenerate skew-symmetric bilinear forms can only exist on even-dimensional vector spaces, so symplectic manifolds necessarily have even dimension. In dimension 2, a symplectic manifold is just a surface endowed with an area form and a symplectomorphism is an area-preserving diffeomorphism. The phase space of a mechanical system is a symplectic manifold and they made an implicit appearance already in the work of Joseph Louis Lagrange on analytical mechanics and later in Carl Gustav Jacobi's and William Rowan Hamilton's formulations of classical mechanics.

By contrast with Riemannian geometry, where the curvature provides a local invariant of Riemannian manifolds, Darboux's theorem states that all symplectic manifolds are locally isomorphic. The only invariants of a symplectic manifold are global in nature and topological aspects play a prominent role in symplectic geometry. The first result in symplectic topology is probably the Poincaré–Birkhoff theorem, conjectured by Henri Poincaré and then proved by G.D. Birkhoff in 1912. It claims that if an area preserving map of an annulus twists each boundary component in opposite directions, then the map has at least two fixed points.[16]

Contact geometry

editContact geometry deals with certain manifolds of odd dimension. It is close to symplectic geometry and like the latter, it originated in questions of classical mechanics. A contact structure on a (2n + 1)-dimensional manifold M is given by a smooth hyperplane field H in the tangent bundle that is as far as possible from being associated with the level sets of a differentiable function on M (the technical term is "completely nonintegrable tangent hyperplane distribution"). Near each point p, a hyperplane distribution is determined by a nowhere vanishing 1-form , which is unique up to multiplication by a nowhere vanishing function:

A local 1-form on M is a contact form if the restriction of its exterior derivative to H is a non-degenerate two-form and thus induces a symplectic structure on Hp at each point. If the distribution H can be defined by a global one-form then this form is contact if and only if the top-dimensional form

is a volume form on M, i.e. does not vanish anywhere. A contact analogue of the Darboux theorem holds: all contact structures on an odd-dimensional manifold are locally isomorphic and can be brought to a certain local normal form by a suitable choice of the coordinate system.

Complex and Kähler geometry

editComplex differential geometry is the study of complex manifolds. An almost complex manifold is a real manifold , endowed with a tensor of type (1, 1), i.e. a vector bundle endomorphism (called an almost complex structure)

- , such that

It follows from this definition that an almost complex manifold is even-dimensional.

An almost complex manifold is called complex if , where is a tensor of type (2, 1) related to , called the Nijenhuis tensor (or sometimes the torsion). An almost complex manifold is complex if and only if it admits a holomorphic coordinate atlas. An almost Hermitian structure is given by an almost complex structure J, along with a Riemannian metric g, satisfying the compatibility condition

- .

An almost Hermitian structure defines naturally a differential two-form

- .

The following two conditions are equivalent:

where is the Levi-Civita connection of . In this case, is called a Kähler structure, and a Kähler manifold is a manifold endowed with a Kähler structure. In particular, a Kähler manifold is both a complex and a symplectic manifold. A large class of Kähler manifolds (the class of Hodge manifolds) is given by all the smooth complex projective varieties.

CR geometry

editCR geometry is the study of the intrinsic geometry of boundaries of domains in complex manifolds.

Conformal geometry

editConformal geometry is the study of the set of angle-preserving (conformal) transformations on a space.

Differential topology

editDifferential topology is the study of global geometric invariants without a metric or symplectic form.

Differential topology starts from the natural operations such as Lie derivative of natural vector bundles and de Rham differential of forms. Beside Lie algebroids, also Courant algebroids start playing a more important role.

Lie groups

editA Lie group is a group in the category of smooth manifolds. Beside the algebraic properties this enjoys also differential geometric properties. The most obvious construction is that of a Lie algebra which is the tangent space at the unit endowed with the Lie bracket between left-invariant vector fields. Beside the structure theory there is also the wide field of representation theory.

Geometric analysis

editGeometric analysis is a mathematical discipline where tools from differential equations, especially elliptic partial differential equations are used to establish new results in differential geometry and differential topology.

Gauge theory

editGauge theory is the study of connections on vector bundles and principal bundles, and arises out of problems in mathematical physics and physical gauge theories which underpin the standard model of particle physics. Gauge theory is concerned with the study of differential equations for connections on bundles, and the resulting geometric moduli spaces of solutions to these equations as well as the invariants that may be derived from them. These equations often arise as the Euler–Lagrange equations describing the equations of motion of certain physical systems in quantum field theory, and so their study is of considerable interest in physics.

Applications

edit| Part of a series on |

| Spacetime |

|---|

Below are some examples of how differential geometry is applied to other fields of science and mathematics.

- In physics, differential geometry has many applications, including:

- Differential geometry is the language in which Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity is expressed. According to the theory, the universe is a smooth manifold equipped with a pseudo-Riemannian metric, which describes the curvature of spacetime. Understanding this curvature is essential for the positioning of satellites into orbit around the earth. Differential geometry is also indispensable in the study of gravitational lensing and black holes.

- Differential forms are used in the study of electromagnetism.

- Differential geometry has applications to both Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics. Symplectic manifolds in particular can be used to study Hamiltonian systems.

- Riemannian geometry and contact geometry have been used to construct the formalism of geometrothermodynamics which has found applications in classical equilibrium thermodynamics.

- In chemistry and biophysics when modelling cell membrane structure under varying pressure.

- In economics, differential geometry has applications to the field of econometrics.[17]

- Geometric modeling (including computer graphics) and computer-aided geometric design draw on ideas from differential geometry.

- In engineering, differential geometry can be applied to solve problems in digital signal processing.[18]

- In control theory, differential geometry can be used to analyze nonlinear controllers, particularly geometric control[19]

- In probability, statistics, and information theory, one can interpret various structures as Riemannian manifolds, which yields the field of information geometry, particularly via the Fisher information metric.

- In structural geology, differential geometry is used to analyze and describe geologic structures.

- In computer vision, differential geometry is used to analyze shapes.[20]

- In image processing, differential geometry is used to process and analyse data on non-flat surfaces.[21]

- Grigori Perelman's proof of the Poincaré conjecture using the techniques of Ricci flows demonstrated the power of the differential-geometric approach to questions in topology and it highlighted the important role played by its analytic methods.

- In wireless communications, Grassmannian manifolds are used for beamforming techniques in multiple antenna systems.[22]

See also

edit- Abstract differential geometry

- Affine differential geometry

- Analysis on fractals

- Basic introduction to the mathematics of curved spacetime

- Discrete differential geometry

- Gauss

- Glossary of differential geometry and topology

- Important publications in differential geometry

- Important publications in differential topology

- Integral geometry

- List of differential geometry topics

- Noncommutative geometry

- Projective differential geometry

- Synthetic differential geometry

- Systolic geometry

- Gauge theory (mathematics)

References

edit- ^ Bronstein, M.M., Bruna, J., Cohen, T. and Veličković, P., 2021. Geometric deep learning: Grids, groups, graphs, geodesics, and gauges. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.13478.

- ^ a b c d e f g Struik, D. J. “Outline of a History of Differential Geometry: I.” Isis, vol. 19, no. 1, 1933, pp. 92–120. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/225188.

- ^ Clairaut, A.C., 1731. Recherches sur les courbes à double courbure. Nyon.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Leonhard Euler", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ a b c d e f Spivak, M., 1975. A comprehensive introduction to differential geometry (Vol. 2). Publish or Perish, Incorporated.

- ^ Gauss, C.F., 1828. Disquisitiones generales circa superficies curvas (Vol. 1). Typis Dieterichianis.

- ^ a b c d Struik, D.J. “Outline of a History of Differential Geometry (II).” Isis, vol. 20, no. 1, 1933, pp. 161–191. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/224886

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Non-Euclidean Geometry", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Milnor, John W., (1982) Hyperbolic geometry: The first 150 years, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) Volume 6, Number 1, pp. 9–24.

- ^ 1868 On the hypotheses which lie at the foundation of geometry, translated by W.K.Clifford, Nature 8 1873 183 – reprinted in Clifford's Collected Mathematical Papers, London 1882 (MacMillan); New York 1968 (Chelsea) http://www.emis.de/classics/Riemann/. Also in Ewald, William B., ed., 1996 “From Kant to Hilbert: A Source Book in the Foundations of Mathematics”, 2 vols. Oxford Uni. Press: 652–61.

- ^ Christoffel, E.B. (1869). "Ueber die Transformation der homogenen Differentialausdrücke zweiten Grades". Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik. 70.

- ^ Ricci, Gregorio; Levi-Civita, Tullio (March 1900). "Méthodes de calcul différentiel absolu et leurs applications" [Methods of the absolute differential calculus and their applications]. Mathematische Annalen (in French). 54 (1–2). Springer: 125–201. doi:10.1007/BF01454201. S2CID 120009332.

- ^ a b Dieudonné, J., 2009. A history of algebraic and differential topology, 1900-1960. Springer Science & Business Media.

- ^ a b Fré, P.G., 2018. A Conceptual History of Space and Symmetry. Springer, Cham.

- ^ Hestenes, David (2011). "The Shape of Differential Geometry in Geometric Calculus" (PDF). In Dorst, L.; Lasenby, J. (eds.). Guide to Geometric Algebra in Practice. Springer Verlag. pp. 393–410. There is also a pdf[permanent dead link] available of a scientific talk on the subject

- ^ The area preserving condition (or the twisting condition) cannot be removed. If one tries to extend such a theorem to higher dimensions, one would probably guess that a volume preserving map of a certain type must have fixed points. This is false in dimensions greater than 3.

- ^ Marriott, Paul; Salmon, Mark, eds. (2000). Applications of Differential Geometry to Econometrics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65116-5.

- ^ Manton, Jonathan H. (2005). "On the role of differential geometry in signal processing". Proceedings. (ICASSP '05). IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 2005. Vol. 5. pp. 1021–1024. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.2005.1416480. ISBN 978-0-7803-8874-1. S2CID 12265584.

- ^ Bullo, Francesco; Lewis, Andrew (2010). Geometric Control of Mechanical Systems : Modeling, Analysis, and Design for Simple Mechanical Control Systems. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-1-4419-1968-7.

- ^ Micheli, Mario (May 2008). The Differential Geometry of Landmark Shape Manifolds: Metrics, Geodesics, and Curvature (PDF) (Ph.D.). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2011.

- ^ Joshi, Anand A. (August 2008). Geometric Methods for Image Processing and Signal Analysis (PDF) (Ph.D.).

- ^ Love, David J.; Heath, Robert W., Jr. (October 2003). "Grassmannian Beamforming for Multiple-Input Multiple-Output Wireless Systems" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 49 (10): 2735–2747. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.106.4187. doi:10.1109/TIT.2003.817466. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-02.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

edit- Ethan D. Bloch (27 June 2011). A First Course in Geometric Topology and Differential Geometry. Boston: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-8176-8122-7. OCLC 811474509.

- Burke, William L. (1997). Applied differential geometry. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26929-6. OCLC 53249854.

- do Carmo, Manfredo Perdigão (1976). Differential geometry of curves and surfaces. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-212589-5. OCLC 1529515.

- Frankel, Theodore (2004). The geometry of physics : an introduction (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53927-2. OCLC 51855212.

- Elsa Abbena; Simon Salamon; Alfred Gray (2017). Modern Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces with Mathematica (3rd ed.). Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC. ISBN 978-1-351-99220-6. OCLC 1048919510.

- Kreyszig, Erwin (1991). Differential Geometry. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-66721-8. OCLC 23384584.

- Kühnel, Wolfgang (2002). Differential Geometry: Curves – Surfaces – Manifolds (2nd ed.). Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-3988-1. OCLC 61500086.

- McCleary, John (1994). Geometry from a differentiable viewpoint. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-13311-4. OCLC 915912917.

- Spivak, Michael (1999). A Comprehensive Introduction to Differential Geometry (5 Volumes) (3rd ed.). Publish or Perish. ISBN 0-914098-72-1. OCLC 179192286.

- ter Haar Romeny, Bart M. (2003). Front-end vision and multi-scale image analysis : multi-scale computer vision theory and applications, written in Mathematica. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. ISBN 978-1-4020-1507-6. OCLC 52806205.

External links

edit- "Differential geometry", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- B. Conrad. Differential Geometry handouts, Stanford University

- Michael Murray's online differential geometry course, 1996 Archived 2013-08-01 at the Wayback Machine

- A Modern Course on Curves and Surfaces, Richard S Palais, 2003 Archived 2019-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Richard Palais's 3DXM Surfaces Gallery Archived 2019-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Balázs Csikós's Notes on Differential Geometry

- N. J. Hicks, Notes on Differential Geometry, Van Nostrand.

- MIT OpenCourseWare: Differential Geometry, Fall 2008