| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. |

| Eewilson/Spilosum | |

|---|---|

| |

| S. pilosum var. pilosum | |

| |

| S. pilosum var. pringlei | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Symphyotrichum |

| Species: | S. pilosum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Symphyotrichum pilosum | |

| Varieties[2] | |

| |

| |

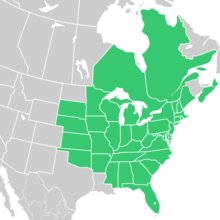

| Native distribution of both varieties of S. pilosum.[3][4] See text for varietal maps. | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Basionym

Species

Variety pringlei

| |

Symphyotrichum pilosum (formerly Aster pilosus) is a perennial, herbaceous, flowering plant in the Asteraceae family native to central and eastern North America. It is commonly called hairy white oldfield aster, frost aster, white heath aster, heath aster, hairy aster, common old field aster, old field aster, awl aster, nailrod, and steelweed. There are two varieties: Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pilosum, known by the common names previously listed, and Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei, known as Pringle's aster. Both varieties are conservationally secure globally and in most provinces and states where they are native.

The varieties differ in morphology, distribution, and habitat; S. pilosum var. pilosum is hairy, and S. pilosum var. pringlei is hairless, or nearly so. S. pilosum var. pilosum is the more widespread of the two and grows in various dry habitats, often with weeds. S. pilosum var. pringlei grows in higher-quality calcium-rich ecosystems, often with many non-weedy companion flora. S. pilosum has been introduced to several European and Asian countries.

The species usually reaches heights between 20 centimeters (8 inches) and 120 cm (4 feet). It blooms late summer to late fall with composite flowers that are 13 to 19 millimeters (0.5 to 0.75 in) wide and have white ray florets and yellow disk florets. S. pilosum var. pilosum and the rare endemic Symphyotrichum kentuckiense breed and produce a hybrid that has been named Symphyotrichum × priceae. S. pilosum also hybridizes with other Symphyotrichum species. S. pilosum var. pringlei has been used in the cultivar industry, and it and its cultivar 'Ochtendgloren' have won the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.

Description edit

Symphyotrichum pilosum is a perennial, herbaceous, flowering plant that reaches heights between 20 cm (8 in) and 120 cm (4 ft); some plants can be as short as 5 cm (2 in) and others up to or taller than 150 cm (5 ft).[5] It flowers late summer to late fall, in the north ending in October and farther south in December.[6]

There are two varieties: Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pilosum and S. pilosum var. pringlei. They differ in morphology, chromosome count, distribution, and habitat.[5][3][4] S. pilosum var. pilosum is the autonym, with hairy stems and leaves. It is widespread and often weedy.[3] S. pilosum var. pringlei is hairless, less common, and often grows in high-quality habitats.[7]

Roots and stems edit

The roots of S. pilosum have bulky and branched caudices that sometimes have long rhizomes[5] which store nutrients for the next year's flowering.[6] The plant is cespitose with one to five straight stems.[5] The two varieties have different stem surfaces: S. pilosum var. pilosum has hairy stems (pilose to densely hirsute),[3] and S. pilosum var. pringlei has stems with no hair (glabrous)[4] or at most, they are hairy in vertical lines.[5]

Leaves edit

S. pilosum has thin,[5] alternate, and simple leaves.[8] Those of S. pilosum var. pilosum are hairy,[3] and those of S. pilosum var. pringlei are hairless or nearly hairless.[4] Leaves grow at the base, on the stem, and in the inflorescence branches. The ground leaves (basal leaves) are either sessile or have very short leafstalks with sheathing wings fringed with hairs on the margins (edges), meaning they are ciliate. They are oblanceolate or obovate to spatulate with obtuse to rounded tips, and their bases are attenuate.[a] Their margins are slightly wavy or saw-toothed, mostly near the tips. Basal leaves range in lengths from 10 to 60 mm (0.4 to 2 in) and widths from 5 to 15 mm (0.2 to 0.6 in). They grow in a rosette and develop prior to flowering, then wither or die during plant growth. At the time of flowering, another rosette of basal leaves forms.[5]

Lower stem leaves usually wither by flowering, and they often have small leaves in clusters at the stem nodes. These stem leaves are entire (smooth on the margins) to saw-toothed and have soft cilia. Their tips are attenuate, and the leaves are elliptic-oblanceolate, elliptic-oblong, linear-lanceolate, or linear-oblanceolate. The leaf bases can be petiolate or subpetiolate to subsessile, and they clasp the stem with attenuate to cuneate bases[b] with wings. Lengths are from 40 to 102 mm (1.6 to 4.0 in) and widths from 5 to 25 mm (0.2 to 1 in), getting progressively smaller as they approach the upper portion of the stem.[5]

Distal leaves, higher on the stem and on the branches with the flower heads, are lance-oblong, linear-lanceolate, linear, linear-oblanceolate, or linear-subulate. Their margins are entire or saw-toothed, and they are sessile with cuneate bases. Lengths range from 10 to 100 mm (0.4 to 4 in) and widths are 1 to 8 mm (0.04 to 0.3 in). The leaves get progressively smaller near the inflorescences; closest to the flower heads, their sizes are abruptly reduced.[5]

Flowers edit

The flower heads of Symphyotrichum pilosum are 13 to 19 mm (0.5 to 0.75 in) wide[8] and grow on branches that are 100 mm (4 in) or less at wide angles off the stem (divaricate). They also may be ascending and arching. They are open, generally not crowded, and have many small leaves. Each flower head is on a peduncle that is usually 5 to 30 mm (0.20 to 1.2 in), sometimes as long as 50 mm (2 in). They get shorter the farther up the branch they grow which then causes the inflorescence to look like a pyramid. The peduncles of S. pilosum var. pilosum have dense and bristly hairs (hispid), and those of S. p. var. pringlei are hairless (glabrous). Both varieties have from 7 to 25 or more bracts that are glabrous and may have cilia.[5]

Involucres and phyllaries edit

Flower heads of all members of the Asteraceae family have phyllaries which are small, specialized leaves that look like scales. Together they form the involucre that protects the individual flowers in the head before they open.[c][9] The involucres of Symphyotrichum pilosum are campanulate to cylindro-campanulate in shape (bell to cylinder-bell) and usually 3.5 to 5.1 mm (0.14 to 0.20 in) in length, although they can be as short as 2.5 mm (0.1 in) and as long as 6.5 mm (0.26 in).[5]

The phyllaries of S. pilosum var. pilosum have small and sparse hairs, meaning they are hirsutulous, and those of variety pringlei are glabrous. Both varieties have phyllaries in 4 to 6 rows that are unequally aligned, and rarely subequally aligned. The phyllaries are appressed or slightly spreading, and the outer ones are oblong-lanceolate in shape, while the inner are linear. They have green chlorophyllous zones that are lanceolate to lance-rhombic with apices (tips) that have either short and sharp points (acute) or taper to long points (acuminate). Their margins appear white or light green, but they are actually translucent and may appear nibbled or worn away (in botanical terms, they are scarious and erose). They are inrolled at the tips.[5]

Florets edit

Each flower head is made up of ray florets and disk florets. The 16 to 28[d] ray florets grow in one series and are usually white, rarely pinkish or bluish. They are usually between 5.4 and 7.5 mm (0.21 and 0.30 in) in length, but can be as short as 4 mm (0.16 in) and as long as 11 mm (0.43 in). They are 0.4 to 1.7 mm (0.016 to 0.067 in) wide[5] and they make up about 45% of the total number of florets on a flower head.[10]

The disks have 17 to 39[e] florets that start out as yellow and after opening, turn reddish purple or brown after pollination. Each disk floret is 3.4 to 4.1 mm (0.13 to 0.16 in) in depth, sometimes up to 5.5 mm (0.22 in), and is made up of 5 petals, collectively a corolla, which open into 5 lanceolate lobes comprising 0.4 to 1 mm (0.02 to 0.04 in) of the depth of the floret.[5]

Fruit edit

The fruits of Symphyotrichum pilosum are not true achenes but are cypselae, resembling an achene and surrounded by a calyx sheath. This is true for all members of the Asteraceae family.[11] After pollination, they become off-white or gray with an oblong-obovoid shape, 1 to 1.5 mm (0.04 to 0.06 in) in length, and 0.5 to 0.7 mm (0.02 to 0.03 in) in width. They have 4 to 6 nerves and a few stiff, slender bristles on their surfaces (strigillose). Their pappi (tufts of hairs) are white and 3.5 to 4 mm (0.14 to 0.16 in) in length.[5] The seeds mature late in the season but cannot germinate at low temperatures. They are dispersed by the fall and winter winds and germinate when temperatures become warm in the spring.[6]

Chromosomes edit

S. pilosum has a monoploid number (also called base number) of eight chromosomes (x = 8).[12] There are plants of S. pilosum var. pilosum with four and six sets of the chromosomes, tetraploid with 32 total and hexaploid with 48 total, respectively. These cytotypes occur regularly, with occasional pentaploids (five sets) that have 40 in total.[13] S. pilosum var. pringlei is hexaploid with a total chromosome count of 48.[4]

Differences in morphology have been found between tetraploids and hexaploids of S. pilosum var. pilosum in southwestern Ontario, including involucre and floret sizes,[13] branch length, leaf sizes, and others; they are consistently smaller on tetraploids than on hexaploids. Additionally, the leaf hair on tetraploids is denser than on hexaploids.[14]

Similar species edit

Several Symphyotrichum species can be confused with S. pilosum.[15]

S. depauperatum edit

S. pilosum var. pringlei and Symphyotrichum depauperatum are superficially similar; at a detailed level, a difference can be seen in the involucres and phyllaries.[15] S. pilosum var. pringlei has bell to cylinder-bell shaped involucres,[5] whereas S. depauperatum has only cylinder-bell shaped involucres.[16] S. pilosum var. pringlei has spreading phyllaries with chlorophyllous tips and inrolled margins. S. depauperatum always has tightly appressed phyllaries.[15]

S. pilosum var. pringlei and S. depauperatum flower heads

-

S. pilosum var. pringlei

S. ericoides edit

Symphyotrichum ericoides is a species often confused with S. pilosum but can be differentiated by its flower heads and phyllaries. S. ericoides has smaller flower heads than S. pilosum,[5] and whereas the phyllaries of S. pilosum are inrolled at the tips, the tips of S. ericoides are spinulose.[15] The name Aster ericoides has been used incorrectly to represent Symphyotrichum pilosum (and Aster pilosus) in published floras and the horticultural industry.[5]

S. pilosum var. pilosum and S. ericoides phyllaries

-

S. pilosum var. pilosum

S. kentuckiense edit

S. pilosum and S. kentuckiense flower heads

S. lanceolatum edit

S. pilosum var. pringlei and S. lanceolatum flower heads

-

S. pilosum var. pringlei

S. parviceps edit

S. pilosum var. pilosum and S. parviceps flower heads

-

S. pilosum var. pilosum

S. porteri edit

S. pilosum var. pringlei and S. porteri inflorescences

-

S. pilosum var. pringlei

Taxonomy edit

Etymology edit

The specific epithet, second part of the scientific name, pilosum is from Latin pilosus meaning "with long soft hairs".[17] The species has the common names of hairy white oldfield aster,[18] frost aster, white heath aster, heath aster, hairy aster, common old field aster, old field aster,[19] awl aster,[20] nailrod,[21] and steelweed.[19] Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei is commonly known as Pringle's aster[4] and was named for American botanist Cyrus Guernsey Pringle.[7]

Varieties edit

Two varieties were accepted by Plants of the World Online (POWO) as of November 2022[update].[2] S. pilosum var. pilosum, the autonym, has hairy stems and leaves. It is widespread and often weedy.[3] S. pilosum var. pringlei is hairless, or nearly so,[4] and grows in calcium-rich ecosystems[7] with many companion flora.[22]

History edit

Symphyotrichum pilosum

- basionym: Aster pilosus

- botanists

- specimen collector: French botanist Louis Claude Marie Richard; source specimen & IPNI

- collected date(s): not on sheet

- authority: German botanist Carl Ludwig Willdenow Willd.

- Sp. Pl., ed. 4 [Willdenow] 3(3): 2025 (1803)

- protologue: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/667414/

- citation: [23]

- date/year: April–December 1803

- called it "Weisshaarige Sternblume" ("White-haired Starflower")

- "Habitat in America boreali in regione Illinoensium" ("He lives in North America in the Illinois region")

- synonym(s): Aster villosus Michx. which was illegal and could not be used even though it was published 19 March 1803

- subsequent classifications (do this in chronological order)

- Aster chrysogonii Sennen: French botanist Frère Sennen

- Aster ericoides var. pilosus (Willd.) Porter: American botanist Thomas Conrad Porter

- Aster ericoides var. platyphyllus Torr. & A.Gray: American botanists John Torrey and Asa Gray

- Aster ericoides f. villosus (Torr. & A.Gray) Voss: German botanist Andreas Voss

- Aster ericoides var. villosus Torr. & A.Gray

- Aster juniperinus E.S.Burgess: American botanist Edward Sandford Burgess

- Aster pilosus var. demotus S.F.Blake: American botanist Sidney Fay Blake

- Aster pilosus var. platyphyllus S.F.Blake

- Aster pilosus f. pulchellus Benke: ("German-born American botanist": best source I found for this is https://www.manitowoccountyhistory.org/stories/benke, the Manitowoc County, Wisconsin Historical Society) Hermann Conrad Benke

- Aster villosus Michx., nom. illeg.: French botanist André Michaux

- Symphyotrichum pilosum (Willd.) G.L.Nesom: American botanist Guy L. Nesom

Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei

- basionym: Aster ericoides var. pringlei

- botanists

- specimen collector: American botanist Cyrus Guernsey Pringle (for whom it was named); source specimen

- collected date(s): 3 September 1879, 24 September 1880; source specimen

- authority: Asa Gray A.Gray

- Syn. Fl. N. Amer. 1, pt. 2: 184 (1884) – pp. 184–185

- protologue: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/11296202/

- year: 1884

- citation: [24]

- subsequent classifications (do this in chronological order)

- Aster faxonii Porter: Thomas Conrad Porter

- Aster pilosus var. pringlei S.F.Blake

- Aster polyphyllus Willd., nom. illeg.

- Aster pringlei Britton: American botanist Nathaniel Lord Britton

- Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei (A.Gray) G.L.Nesom: Guy L. Nesom

Type specimens edit

As of November 2022[update], the holotype of Aster pilosus Willd. was stored at the Herbarium Berolinense, Berlin Botanical Garden and Botanical Museum, Germany,[25] and the Aster ericoides var. pringlei A.Gray holotype was stored at the United States National Herbarium, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[26] Images of both specimen sheets are shown in this section and are available for more detailed viewing at the virtual online collection websites of their respective herbaria.[25][26]

-

Aster ericoides var. pringlei A.Gray

holotype stored at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution[26]

Classification edit

Symphyotrichum pilosum is classified in subgenus Symphyotrichum section Symphyotrichum subsection Porteriani. This subsection contains four species in addition to S. pilosum: S. depauperatum (serpentine aster), S. kentuckiense (Kentucky aster), S. parviceps (smallhead aster), and S. porteri (Porter's aster). Two commonalities among the five species are their inrolled phyllaries and their summer- and fall-forming basal leaf rosettes.[12]

-

Symphyotrichum

subg. Symphyotrichumsect. Conyzopsis[ref 2]: 271sect. Occidentales[ref 2]: 271sect. Turbinelli[ref 1]: 133sect. Symphyotrichum[ref 2]: 268Cladogram references

- ^ a b c d e Semple, J.C.; Heard, S.B.; Brouillet, L. (2002). "Cultivated and Native Asters of Ontario (Compositae: Astereae)". University of Waterloo Biology Series. 41. Ontario: University of Waterloo: 1–134.

- ^ a b c d e Nesom, G.L. (September 1994). "Review of the Taxonomy of Aster sensu lato (Asteraceae: Astereae), Emphasizing the New World Species". Phytologia. 77 (3) (published 31 January 1995): 141–297. ISSN 0031-9430. Retrieved 23 August 2021 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Distribution edit

Native edit

Both varieties of Symphyotrichum pilosum are native to central and eastern Canada and the United States, with the more common being S. pilosum var. pilosum.[3][4]

Variety pilosum edit

Sources differ slightly on the distribution of S. pilosum var. pilosum. According to Flora of North America (FNA), it is native from west starting in Minnesota, then east to Maine, including Ontario and Québec; south along the Atlantic Seaboard including most southern and eastern states; the entire Midwest; the states bordering the Mississippi River except Louisiana; then with a northwest border to Arkansas; and, four Great Plains states, from south to north, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, and South Dakota. States on the Atlantic Seaboard with no reported presence are Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Rhode Island, and Vermont, plus West Virginia. FNA reports that it has been introduced to the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.[3]

POWO and NatureServe provide slightly different distribution information on this variety. According to POWO, it also is present in and native to Maryland, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. Like FNA, however, POWO reports that it is an introduced species in British Columbia.[27] NatureServe's map for S. pilosum var. pilosum differs from FNA's with an additional introduced presence on Prince Edward Island; no presence in New Hampshire, Nebraska, or South Dakota; and, a presence in Connecticut, Delaware, Louisiana, Maryland, Rhode Island, and Washington, D.C.[28]

Variety pringlei edit

S. pilosum var. pringlei is an east-central and northeastern North American variety, and according to FNA and POWO, it is native to the area encompassing Minnesota in the northwest then east to Québec and Nova Scotia, in the United States on the Atlantic Seaboard south to North Carolina, then northwest to Kentucky, Illinois, and then north to Wisconsin.[4][29] NatureServe differs and includes a presence for this variety in Arkansas, Georgia, South Carolina, and Tennessee.[30]

as reported in Flora of North America (FNA)

Introduced edit

As of November 2022[update], S. pilosum var. pilosum was reported by NatureServe as an introduced species in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island;[28] and, by POWO in the countries of Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain, India, Italy, Korea, Netherlands, and Spain.[27] As of August 2022[update], it was not on the European Union's List of invasive alien species of Union concern.[31]

Habitat edit

Variety pilosum habitat edit

S. pilosum var. pilosum is tolerant of harsh growing conditions.[22] It usually is found at elevations between sea level and 1,000 meters (3,300 feet)[3] in disturbed areas such as fallowed land,[22] old fields, roadsides,[3] salted roadsides, railroads, pastures,[17] landfills, and quarries. It occurs less frequently[22] in natural prairies, open deciduous woods,[3] limestone outcrops,[32] and, very uncommonly, wetlands.[22] Hexaploids of this variety are usually founds in habitats that were once covered in glaciers.[14]

Variety pringlei habitat edit

The presence of S. pilosum var. pringlei can be indicative of a high-quality remnant natural area.[34] It is common in calcium-rich ecosystems such as calcareous grasslands and fens,[7] limestone alvars,[35] shale outcrops,[22] and marly pannes.[f][7] It also has been found in various partially-sandy or sandy areas,[22] on moraine cliffs along lakes in woodland openings, and in environments similar to these.[7] It can be found in habitats attractive to S. pilosum var. pilosum almost as equally as in the higher-quality ones previously mentioned.[22] Elevations of occurrences are from sea level to 1,100 meters (3,600 feet), sometimes higher.[4]

Habitat ratings edit

Wetland indicator statuses edit

Symphyotrichum pilosum is categorized on the United States National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) with the wetland indicator status rating of Facultative (FAC) in the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain (AGCP) and the Eastern Mountains and Piedmont (EMP) regions. The FAC rating means that S. pilosum is likely to occur either in wetlands or non-wetlands. It is categorized Facultative Upland (FACU) in the Arid West (AW), Great Plains (GP), Midwest (MW), Northcentral and Northeast (NCNE), and Western Mountains, Valleys, and Coast (WMVC) regions. Rating FACU means that it usually occurs in non-wetlands within its range, but can occasionally be found in wetlands.[36]

Coefficients of conservatism edit

Symphyotrichum kentuckiense has coefficients of conservatism (C-values) in the Floristic Quality Assessment (FQA)[37][38] of 7 and 8 depending on evaluation region.[39] The higher the C-value, the lower tolerance the species has for disturbance and the greater the likelihood that it is growing in a presettlement natural community.[40] When it grows in the Appalachian Mountain EPA Ecoregions of 67 and 68, S. kentuckiense has a C-value of 7. In the Interior Plateau EPA Ecoregions of 71 and 72, its C-value is 8.[39] Both of these C-values mean that its populations are found in high-quality remnant natural areas with little environmental degradation but can tolerate some periodic disturbance.[40]

For example, in the Atlantic coastal pine barrens of Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island, S. lateriflorum has been given a C-value of 1, meaning its presence in locations of that ecoregion provides little or no confidence of a remnant habitat.[41] In contrast, in the Dakotas, S. lateriflorum has a C-value of 10, meaning its populations there are not weedy and are restricted to only remnant habitats which have a very low tolerance for environmental degradation.[42]

- Indiana 2004 Rothrock, P.E. 2004. Floristic quality assessment in Indiana: The concept, use, and development of coefficients of conservatism. Final Report for ARN A305-4-53, EPA Wetland Program Development Grant CD975586-01. native Asteraceae Symphyotrichum pilosum v. pringlei smooth white aster 5

- Indiana 2019 Update of 2004 Indiana database native Asteraceae Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei smooth white aster SYMPIP 5 3 forb perennial

- Delaware 2013 McAvoy, W.A. 2013. The Flora of Delaware Online Database. Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife, Species Conservation and Research Program, Smyrna, Delaware. http://www.wra.udel.edu/de-flora/Introduction/ native Asteraceae Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei; aster pilosus var. demotus hairy heath aster 2 5 forb perennial

- Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain 2012 Mid-Atlantic Wetland Workgroup (MAWWG). 2012. Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) calculator. native Asteraceae Symphyotrichum pilosum var pringlei SYPIP2 1 0 forb perennial

- Mid-Atlantic Piedmont Region 2012 Mid-Atlantic Wetland Workgroup (MAWWG). 2012. Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) calculator. native Asteraceae Symphyotrichum pilosum var pringlei SYPIP2 1 0 forb perennial

- https://universalfqa.org/view_database/25

- Mid-Atlantic Ridge and Valley Region 2012 Mid-Atlantic Wetland Workgroup (MAWWG). 2012. Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) calculator. native Asteraceae Symphyotrichum pilosum var pringlei SYPIP2 1 0 forb perennial

- Mid-Atlantic Allegheny Plateau (non-glaciated) 2012 Mid-Atlantic Wetland Workgroup (MAWWG). 2012. Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) calculator. native Asteraceae Symphyotrichum pilosum var pringlei SYPIP2 1 0 forb perennial

- Mid-Atlantic Allegheny Plateau (glaciated) 2012 Mid-Atlantic Wetland Workgroup (MAWWG). 2012. Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) calculator. native Asteraceae Symphyotrichum pilosum var pringlei SYPIP2 1 0 forb perennial

- Interior Plateau (EPA Ecoregions 70,71,72), of KY, TN, and AL 2013 Gianopulos, K. 2014. Coefficient of Conservatism Database Development for Wetland Plants Occurring in the Southeast United States. NC Dept. of Envir. Quality, Div. of Water Resources: Wetlands Branch. Report to the EPA. developed with 15 expert botanists native Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei pringles aster SYPIP2 9 forb perennial

- Flora of the Chicago Region 2017 Flora of the Chicago Region UFQA Database. 2018. Kenneth Johnson. [As per Flora of the Chicago Region: A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis. 2017. Gerould Wilhelm and Laura Rericha. Indiana Academy of Science. Indianapolis, IN.] native Asteraceae Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei pringles aster SYMPVP 9 -1 forb perennial

- Chicago Region USACE 2017 https://www.lrc.usace.army.mil/Missions/Regulatory/FQA.aspx native Asteraceae Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei white oldfield american-aster SYMPILP 9 1 forb perennial

Associate species with S. pilosum have similar C-values. For example, where it and its varieties are native, Salix myricoides, an associate of S. pilosum var. pringlei, has C-values of 5 through 10, mostly 7 and above,[43] meaning it is also a species indicative of high-quality remnant habitats.[40]

Ecology edit

Reproduction edit

S. pilosum's primary means of reproduction is through pollination, which occurs with the help of short or mid-length tongued insects from dawn to dusk. These insects are able to manipulate the small flower heads successfully and transfer pollen from one plant to another. The use of pollen from one plant to fertilize another is called allogamy (or cross-pollination) and is required by this species. Any occasional self-pollination produces only a few viable seeds. The seeds mature late in the season but cannot germinate at low temperatures. They are dispersed by the fall and winter winds and germinate in the spring.[6] The ray florets of S. lateriflorum bloom earlier and are likely receptive to pollen longer than the disk florets.[44]

When the disk floret of S. lateriflorum is blooming, the corolla lobes separate to about 50–75% the length of the corolla.[45]

When pollination is complete, the seeds become ripe in 3–4 weeks, hardening and developing pappi. They are then wind dispersed. Usually, the seeds will have their dried corollas attached as they depart.[46]

Hybridization edit

S. pilosum produces hybrids with other Symphyotrichum species that can survive and reproduce beyond the first generation (beyond F1 hybridization). These surviving hybrid populations are called hybrid swarms,[47] variable groups of hybrids that, rather than being sterile, can reproduce with its parent species or each other.[48] S. pilosum hybrids can interbreed with other hybrid individuals and backcross with their parent species. Its ability to do this has made S. pilosum valuable to the cut flower and cultivar industries.[47]

S. pilosum var. pilosum and the rare endemic Symphyotrichum kentuckiense[49] breed and produce an F1 hybrid that has been named Symphyotrichum × priceae.[50] The parent plants are both within subsection Porteriani[12] and have similar characteristics. However, S. kentuckiense is glabrous rather than pilose, and its flower heads are larger than those of S. pilosum, at about 25 mm (1 in) wide,[51] compared to those of S. pilosum, which are 13 to 19 mm (0.5 to 0.75 in) wide.[8] The heads of S. kentuckiense have blue,[52] blue-violet,[53] pink, or purple ray florets.[51] The hybrid is a somewhat hairy plant rather than a hairless one, and its characteristics are intermediate between its parents.[52]

S. × priceae, and S. pilosum var. pilosum

Putative F1 hybrids of Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pilosum with twelve other species of the genus have been reported: S. cordifolium (common blue wood aster[54]), S. drummondii (Drummond's aster[55]), S. dumosum (bushy aster[56]), S. laeve (smooth aster[57]), S. lanceolatum (panicled aster[58]), S. novi-belgii (New York aster[59]), S. oolentangiense (skyblue aster[60]),[47] S. parviceps (smallhead aster[61]), S. praealtum (willowleaf aster[62]), S. racemosum (small white aster[63]),[64] S. tradescantii (shore aster[65]), and S. urophyllum (arrowleaf aster[66]).[47] Additionally, based on the discovery of pentaploids of S. pilosum var. pilosum, it has been determined that intraspecific hybridization has occurred between varieties pilosum and pringlei or between the tetraploid and hexaploid cytotypes of variety pilosum.[67]

Fungal associates edit

When growing in disturbed communities, S. pilosum has been found to contain beneficial arbuscular mycorrhizae in its roots.[6] Four species of rust fungus have been recorded on the leaves of Symphyotrichum pilosum. Coleosporium asterum infects the abaxial surfaces with small yellow to orange pustules.[68] The rust Puccinia cnici-oleracei (formerly named Puccinia asteris) infects the leaves with dark spores on their abaxial sides.[69] Puccinia dioicae produces pale spots with pustules of similar color or darker in the center.[70] Mildew on S. pilosum occurs but has not been found to do lasting damage to the plant.[71]

Plant associates edit

Variety pilosum plant associates edit

Variety pilosum grows in plant communities with native and non-native grasses and flowering plants.

Grasses edit

S. pilosum var. pilosum can be found growing among grasses that have been introduced to North America, including Bromus inermis (smooth bromegrass), Poa compressa (Canada bluegrass), Poa pratensis (Kentucky bluegrass), and Schedonorus arundinaceus (tall fescue).[17]

Flowering plants edit

S. pilosum var. pilosum can be seen growing among North American native flowering plants such as Solidago canadensis (Canada goldenrod), Solidago altissima (tall goldenrod),[72] Achillea millefolium (common yarrow), Asclepias syriaca (common milkweed), Erigeron annuus (daisy fleabane), Ambrosia artemisiifolia (common ragweed), and Ambrosia trifida (giant ragweed).[17] On salted roadsides, it can occur with Symphyotrichum subulatum (eastern annual saltmarsh aster).[73]

Variety pilosum also co-occurs with weedy flowering plants that have been introduced to North America, including Cirsium arvense (creeping thistle), Chenopodium album (lamb's quarters), Rumex crispus (curly dock), Daucus carota (Queen Anne's lace), Securigera varia (crownvetch), Lactuca serriola (prickly lettuce), Melilotus albus (white sweetclover), Melilotus officinalis (sweet yellow clover), and Pastinaca sativa (parsnip).[17]

Variety pringlei plant associates edit

Pringle's aster has been found among 120 associate species in southwestern Ontario, with 13 to 45 individual species counted in different populations.[22] American botanist and lichenologist Gerould Wilhelm and American biologist Laura Rericha, in their 2017 Flora of the Chicago Region: a Floristic and Ecological Synthesis, list many companion flora. These depend upon the environment in which S. pilosum var. pringlei is growing.[7]

Shrubs edit

Growing near to variety pringlei can be the naturally occurring native North American shrubs Dasiphora fruticosa (shrubby cinquefoil), Prunus pumila (sand cherry), and Salix myricoides (bayberry willow).[7]

Sedges and grasses edit

Pringle's aster grows among many North American native sedges and grasses. Associate sedges include the Carex species C. aurea (golden sedge), C. buxbaumii (Buxbaum's sedge), C. richardsonii (Richardson's sedge[74]), C. sterilis (dioecious sedge), C. stricta (upright sedge), C. tetanica (rigid sedge[75]), and C. viridula (little green sedge). Other sedges include Cladium mariscoides (smooth sawgrass), Eleocharis elliptica (elliptic spikerush[76]), Eleocharis rostellata (beaked spikerush), Rhynchospora capillacea (needle beaksedge), and Scleria verticillata (low nutrush).[7]

Flowering plants edit

S. pilosum var. pringlei can be with or near fellow native taxa of the tribe Astereae, including the goldenrods Solidago nemoralis subsp. decemflora (gray goldenrod),[g] S. ohioensis (Ohio goldenrod),[h] S. patula (roundleaf goldenrod), S. ptarmicoides (prairie goldenrod),[i] S. riddellii (Riddell's goldenrod),[j] as well as fellow American asters Doellingeria umbellata (tall flat-topped white aster) and Symphyotrichum dumosum (bushy aster).[7]

Other companion flowering plants native to North America include Argentina anserina (silverweed), Artemisia campestris subsp. caudata (field sagewort[81]), Cirsium muticum (swamp thistle), Coreopsis lanceolata (lance-leaved coreopsis), Euphorbia corollata (flowering spurge), Eutrochium maculatum (spotted joe-pyeweed), Helianthus giganteus (giant sunflower), Helianthus occidentalis (fewleaf sunflower), Hypericum kalmianum (Kalm's St. Johns wort), Liatris aspera (rough blazing star),[k] Liatris cylindracea (barrelhead blazing star), Liatris pycnostachya (prairie blazing star), Lithospermum caroliniense var. croceum (hairy puccoon),[l] Lithospermum incisum (fringed puccoon), Oenothera clelandii (Cleland's evening primrose[84]), Oxypolis rigidior (cowbane), Pedicularis lanceolata (swamp lousewort), Polygonum tenue (slender knotweed), Rudbeckia hirta var. pulcherrima (black-eyed Susan), Sabatia angularis (rosepink), and Zizia aurea (golden alexanders).[7]

Animal associates edit

Mammals edit

Birds edit

During the cold months, seeds from plants in the Symphyotrichum genus are food to small, seed-eating, native North American birds such as American goldfinches (Spinus tristis), American tree sparrows (Spizelloides arborea), black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus), house finches (Haemorhous mexicanus), pine siskins (Spinus pinus), and song sparrows (Melospiza melodia). The American tree sparrow and the American goldfinch will grasp the upper branches and shake them by strongly fluttering their wings so that the seeds will fall to the ground.[85]

Bees edit

The flower heads of S. pilosum are visited by many bee species during daylight hours.[6] Females of Melissodes druriella (Drury's long-horned bee[86]) and the mining bee Pseudopanurgus compositarum are oligoleges (specialized bee pollinators) of the short florets of late-season blooming species in the Asteraceae family and can be found frequenting this plant.[87] Symphyotrichum species flowers are attractive to other specialized bees, including Andrena asteris (aster miner[88]), Andrena asteroides, Andrena hirticincta (hairy-banded andrena[89]), Andrena nubecula (cloudy-winged miner bee[90]), Andrena placata (peaceful miner bee[91]), Andrena simplex (simple miner bee[91]), and Colletes simulans (spine-shouldered cellophane bee[92]).[8]

Flower visitors of S. pilosum also include the introduced Apis mellifera (western honey bee[93]) and many bees native to North America, including Augochlorella aurata (golden green sweat bee[94]); Bombus impatiens (common eastern bumblebee[95]); small carpenter bees of genus Ceratina,[96] including C. calcarata, C. dupla, and C. strenua; the sweat bees Halictus ligatus (ligated furrow bee[97]) and Lasioglossum ephialtum (nightmarish metallic-sweat bee[98]); and, the large Xylocopa virginica (eastern carpenter bee[99]). Visitations by the wasp Polistes fuscatus (northern paper wasp[100]) occur but not regularly.[6]

- see GLoBi spreadsheet which includes Lasioglossum cressonii; this file Lasioglossum cressonii 77145399.jpg is that insect on one of the white Symphyotrichums, but I can't tell which one

- same with Lasioglossum zephyrus 164067925.jpg

Flies edit

Many fly species visit the flower heads of S. pilosum during the day,[6] including the North American natives Eristalis dimidiata (black-shouldered drone fly[101]), Helophilus fasciatus (narrow-headed marsh fly[102]), and Toxomerus marginatus (margined calligrapher fly[103]); and, the introduced Eristalis arbustorum (European drone fly[104]) and Eristalis tenax (common drone fly[104]).[7]

isn't there something about nectar??

******NEED MUCH MORE TEXT HERE; HOPE I CAN FIND SOMETHING on Hover flies and Symphyotrichum or better yet, S. pilosum******

******NEED MUCH MORE TEXT HERE; HOPE I CAN FIND SOMETHING on Tachinid flies and Blow flies and Symphyotrichum or better yet, S. pilosum******

-

Cylindromyia species

-

Phasia species

-

Lucilia species

Butterflies edit

Pearl crescent: gets nectar from asters too [111] Nectarivory

(common checkered-skipper[112]) on flowers of S. pilosum

From HOSTS: pearl crescent butterfly Phyciodes tharos

- https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/data/hostplants/search/list.dsml?searchPageURL=index.dsml&Familyqtype=starts+with&Family=&PFamilyqtype=starts+with&PFamily=&Genusqtype=starts+with&Genus=&PGenusqtype=starts+with&PGenus=Aster&PSpeciesqtype=starts+with&PSpecies=pilosus

- archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20221110080742/https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/data/hostplants/search/list.dsml?searchPageURL=index.dsml&Familyqtype=starts+with&Family=&PFamilyqtype=starts+with&PFamily=&Genusqtype=starts+with&Genus=&PGenusqtype=starts+with&PGenus=Aster&PSpeciesqtype=starts+with&PSpecies=pilosus

- https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/data/hostplants/index.html

- Robinson, G. S., P. R. Ackery, I. J. Kitching, G. W. Beccaloni & L. M. Hernández, 2010. HOSTS - A Database of the World's Lepidopteran Hostplants. Natural History Museum, London. http://www.nhm.ac.uk/hosts.

Beetles and true bugs edit

Nectarivory W&R p. 1095 beetles from Symphyotrichum:[85] nectar:

- Chauliognathus pensylvanicus (goldenrod soldier beetle[116])

- Diabrotica cristata (black diabrotica[117])

- Epicauta pennsylvanica (black blister beetle[118])

- Olibrus semistriatus (a shining flower beetle[119])

- Myochrous denticollis (southern corn leaf beetle[121])

- page 341: Symphyotrichum pilosum (Willd.) Nesom (Asteraceae) ----------- Myochrous denticollis (Say)

- in Clark, S.M., D.G. LeDoux, T.N. Seeno, E.G. Riley, A.J. Gilbert & J.M. Sullivan. 2004. Host plants of leaf beetle species occurring in the United States and Canada (Coleoptera: Megalopodidae, Orsodacnidae, Chrysomelidae exclusive of Bruchinae). Coleopterists Society, Special Publication no. 2

- url = https://www.coleopsoc.org/publications/special-publications/special-publication-no-2/

- archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20221208080258/https://www.coleopsoc.org/publications/special-publications/special-publication-no-2/

- url-status = live

- archive-date = 8 December 2022

- access-date = 8 December 2022

- title = Host plants of leaf beetle species occurring in the United States and Canada (Coleoptera: Megalopodidae, Orsodacnidae, Chrysomelidae, excluding Bruchinae)

- Shawn M. Clark, Douglas G. LeDoux, Terry N. Seeno, Edward G. Riley, Arthur L. Gilbert, and James M. Sullivan; Special Publication No. 2; Chris Carlton, Editor; The Coleopterists Society; 3294 Meadowview Road, Sacramento, CA 95832-1448; 2004

Ants edit

W&R p. 1095 ants from Symphyotrichum treatment:[85] nectar:

- Formica incerta - ant (no common name) - nectar

- Formica pallidefulva - ant (no common name) - nectar

- Formica subsericea - ant (black field ant, but need a source for that) - nectar

Monomorium minimum (little black ant[124])

Midges edit

midge nesting causes damage to the plant [but I don't think it's recurrent each season unless the midges are... find that out]

Insectivores edit

Allelopathy edit

find stuff here (cite journal already in reference section):

- Jackson, J.R.; Willemsen, R.W. (1 August 1976). "Allelopathy in the first stage of secondary succession on the piedmont of New Jersey". American Journal of Botany. St. Louis, Missouri: Botanical Society of America. 63 (7): 1015–1023. doi:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1976.tb13184.x.

Economic importance edit

Conservation edit

NatureServe lists the species and its varieties with various conservation statuses, and some states and provinces within range do not have statuses. As of November 2022[update], S. pilosum was listed as Globally Secure (G5); and, State Secure (S5) in Ontario, Delaware, Georgia, Iowa, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia.[1]

S. pilosum var. pilosum was listed as a Globally Secure Variety (T5); Secure (S5) in Ontario, Delaware, Georgia, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, and West Virginia; and, Vulnerable (S3) in Québec and Minnesota.[28] S. pilosum var. pringlei also was listed as a Globally Secure Variety (T5); Secure (S5) in Delaware, New Jersey, and Virginia; Apparently Secure (S4) in Ontario and New York; Vulnerable (S3) in Minnesota; Imperiled (S2) in Québec and West Virginia; and, Critically Imperiled (S1) in Arkansas.[30] The global statuses were last reviewed in 2016.[1][28][30]

Uses edit

Medicinal edit

NOTHING LISTED IN THE NAEB DB; TRY AGAIN

I ALSO HAVE A BOOK

Cut flower industry edit

Because of its ability to produce hybrid swarms, S. pilosum can produce hybrids that then may interbreed with other hybrid individuals and backcross with their parent species. This has made it valuable to the cut flower industry.[47]

Gardening edit

The name Aster ericoides has been used incorrectly to represent Symphyotrichum pilosum (and Aster pilosus) in published floras and the horticultural industry.[5]

Picton may, check RHS of course...

Cultivars edit

Because of its ability to produce hybrid swarms, S. pilosum breeding can produce hybrids that can interbreed with other hybrid individuals and backcross with their parent species. This has made it valuable to the cultivar industry.[47] There are several S. pilosum cultivars available ..............

Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei[125] and its cultivar 'Ochtendgloren'[126] have both won the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[127]

NEED TO PERUSE RHS and any other places; INCLUDE Ch&S discussion of cultivation as well as check in S&H&B 2002; may be something in Picton 1999. Picton p. 99–100 as Aster pringlei: 'Monte Cassino' (most frequently grown, p. 99),[128] 'Phoebe' and 'Pink Cushion'[129]

also of pringlei: 'October Glory' RHS; and there are pages for the others on RHS (if they will all ever load)

- https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/340709/symphyotrichum-pilosum-var-pringlei/details

- https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/368446/symphyotrichum-pilosum-var-pringlei-double-flowered-(d)/details

- https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/340829/symphyotrichum-ochtendgloren-(pilosum-var-pringlei-hybrid)/details

- https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/340787/symphyotrichum-pilosum-var-pringlei-october-glory/details

- https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/340788/symphyotrichum-pilosum-var-pringlei-phoebe/details

- https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/340789/symphyotrichum-pilosum-var-pringlei-pink-cushion/details

Notes edit

- ^ Attenuate base is defined as "[h]aving leaf tissue taper down the petiole to a narrow base, always having some leaf material on each side of the petiole". (Copied definiton from Glossary of leaf morphology; see that page's history for attribution.)

- ^ Cuneate base is defined as "[t]riangular, wedge-shaped" where the leaf attaches to the stem. (Part of this definiton was copied from Glossary of leaf morphology; see that page's history for attribution.)

- ^ See Asteraceae § Flowers for more detail.

- ^ Outside range 10 to 38[5]

- ^ Outside range 13 to 67[5]

- ^ Marl is "carbonate-rich mud or mudstone which contains variable amounts of clays and silt". (Copied definition from Marl; see that page's history for attribution.) A panne is a "wetland consisting of a small depression, with or without standing water". (Copied definition from the Wiktionary English noun ecology entry for panne; see that page's history for attribution.)

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017) list the taxon as Solidago decemflora[7] which POWO synonymizes to Solidago nemoralis subsp. decemflora.[77]

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017) list the taxon as Oligoneuron ohioense[7] which POWO synonymizes to Solidago ohioensis.[78]

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017) list the taxon as Oligoneuron album[7] which POWO synonymizes to Solidago ptarmicoides.[79]

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017) list the taxon as Oligoneuron riddellii[7] which POWO synonymizes to Solidago riddellii.[80]

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017) list the taxon as Liatris aspera var. intermedia.[7] which POWO synonymizes to Liatris aspera.[82]

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017) list the taxon as Lithospermum croceum[7] which POWO synonymizes to Lithospermum caroliniense var. croceum.[83]

Citations edit

- ^ a b c NatureServe (2022).

- ^ a b c d POWO (2022).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Brouillet et al. (2006a).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Brouillet et al. (2006b).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Brouillet et al. (2006).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 858.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Wilhelm & Rericha (2017), p. 1105.

- ^ a b c d NC State Extension (n.d.).

- ^ Morhardt & Morhardt (2004), p. 29.

- ^ Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 859.

- ^ Barkley, Brouillet & Strother (2006).

- ^ a b c Semple (2014c).

- ^ a b Semple (2014a).

- ^ a b Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 856.

- ^ a b c d Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 855.

- ^ Brouillet et al. 2006q.

- ^ a b c d e Wilhelm & Rericha (2017), p. 1104.

- ^ USDA (2014).

- ^ a b Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 851.

- ^ Awl aster – Minnesota Wildflowers

- ^ White-Heath Aster (Symphyotrichum pilosum) – Ohio Perennial and Biennial Weed Guide

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 857.

- ^ Willdenow (1803), p. 2025.

- ^ Gray (1884), pp. 184–185.

- ^ a b c Curators Herbarium B (2022).

- ^ a b c United States National Herbarium (2016).

- ^ a b POWO (2022a).

- ^ a b c d NatureServe (2022a).

- ^ POWO (2022b).

- ^ a b c NatureServe (2022b).

- ^ European Commission (2022).

- ^ Semple (2014).

- ^ DCNR (2022).

- ^ ******FQA source(s)******

- ^ Semple (2014b).

- ^ a b CRREL (2020), p. 158.

- ^ Freyman, Master & Packard (2016).

- ^ Freyman (2022).

- ^ a b Gianopulos (2014).

- ^ a b c Rothrock (2004), p. 3.

- ^ Metzler, Ring & Faber-Langendoen (2018).

- ^ Northern Great Plains FQA Panel (2017).

- ^ Freyman (2022), Search for Salix myricoides.

- ^ Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 842.

- ^ Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 837.

- ^ Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 842–843.

- ^ a b c d e f Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 860.

- ^ Cockayne & Allan (1926).

- ^ Weakley (2022).

- ^ POWO (2022i).

- ^ a b Britton (1901), p. 960.

- ^ a b Medley (2021), p. 2.

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006d).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006e).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006f).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006g).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006h).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006i).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006j).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006k).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006l).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006m).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006n).

- ^ Yatskievych (2009).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006o).

- ^ Brouillet et al. (2006p).

- ^ Semple, Heard & Brouillet (2002), p. 84.

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017), p. 1105,1060.

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017), p. 1105,1099.

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017), p. 1105,1098.

- ^ Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 863.

- ^ Chmielewski & Semple (2001), p. 862.

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017), p. 1108.

- ^ USDA (2014a).

- ^ USDA (2014b).

- ^ USDA (2014c).

- ^ POWO (2022e).

- ^ POWO (2022f).

- ^ POWO (2022c).

- ^ POWO (2022d).

- ^ USDA (2014e).

- ^ POWO (2022g).

- ^ POWO (2022h).

- ^ USDA (2014f).

- ^ a b c d Wilhelm & Rericha (2017), p. 1095.

- ^ a b VanDyk (2021), Melissodes druriellus.

- ^ Wilhelm & Rericha (2017), p. 1104,1105.

- ^ a b VanDyk (2021), Andrena asteris.

- ^ a b VanDyk (2021), Andrena hirticincta.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Andrena nubecula.

- ^ a b National General Status Working Group (2022).

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Colletes simulans.

- ^ a b VanDyk (2021), Apis mellifera.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Augochlorella aurata.

- ^ a b VanDyk (2021), Bombus impatiens.

- ^ cirrusimage Ceratina

- ^ a b VanDyk (2021), Halictus ligatus.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Lasioglossum ephialtum.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Xylocopa virginica.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Polistes fuscatus.

- ^ a b Skevington et al. (2019), p. 112.

- ^ a b Skevington et al. (2019), p. 60.

- ^ a b VanDyk (2021), Toxomerus marginatus.

- ^ a b c Skevington et al. (2019), p. 29.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Sphaerophoria contigua.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Spilomyia longicornis.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Syritta pipiens.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Genus Gymnosoma.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Trichopoda pennipes.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Cochliomyia macellaria.

- ^ a b VanDyk (2021), Phyciodes tharos.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Burnsius communis.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Panoquina ocola.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Pieris rapae.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Hylephila phyleus.

- ^ a b VanDyk (2021), Chauliognathus pensylvanicus.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Diabrotica cristata.

- ^ a b VanDyk (2021), Epicauta pensylvanica.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Olibrus semistriatus.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Lygus lineolaris.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Myochrous denticollis.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Alydus eurinus.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Diabrotica barberi.

- ^ VanDyk (2021), Monomorium minimum.

- ^ Royal Horticultural Society (n.d.a).

- ^ Royal Horticultural Society (n.d.b).

- ^ Royal Horticultural Society (2017).

- ^ Picton (1999), p. 99.

- ^ Picton (1999), p. 100.

References edit

- Awl aster – Minnesota Wildflowers

- White-Heath Aster (Symphyotrichum pilosum) – Ohio Perennial and Biennial Weed Guide

- ******FQA source(s)******

- FNA author Ertter IPNI

- FNA author Reveal IPNI

- Dasiphora fruticosa FNA

- FNA author J.R.Rohrer IPNI

- Prunus pumila var. pumila FNA

- Prunus pumila var. susquehanae FNA

- Prunus pumila var. depressa FNA

- Prunus pumila var. besseyi FNA

- FNA author Argus IPNI

- Salix myricoides FNA

- FNA author P.W.Ball IPNI

- FNA author Reznicek IPNI

- Carex aurea FNA

- Carex buxbaumii FNA

- Carex richardsonii FNA

- Carex sterilis FNA

- Carex stricta FNA

- Carex tetanica FNA

- Carex viridula var. viridula FNA

- cirrusimage Ceratina

- Barkley, T.M.; Brouillet, L.; Strother, J.L. (2006). "Asteraceae". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 19. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 10 January 2021 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Britton, N.L. (October 1901). Manual of the Flora of the Northern States and Canada. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 960. Retrieved 1 October 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006). "Symphyotrichum pilosum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 November 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006a). "Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pilosum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 November 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006b). "Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 November 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006c). "Symphyotrichum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 November 2020 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006d). "Symphyotrichum priceae". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 October 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006e). "Symphyotrichum cordifolium". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006f). "Symphyotrichum drummondii". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006g). "Symphyotrichum dumosum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006h). "Symphyotrichum laeve". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006i). "Symphyotrichum lanceolatum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006j). "Symphyotrichum novi-belgii". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006k). "Symphyotrichum oolentangiense". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006l). "Symphyotrichum parviceps". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006m). "Symphyotrichum praealtum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006n). "Symphyotrichum racemosum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006o). "Symphyotrichum tradescantii". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006p). "Symphyotrichum urophyllum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006q). "Symphyotrichum depauperatum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 20. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 18 December 2022 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Chmielewski, J.G.; Semple, J.C. (2001). "The biology of Canadian weeds. 114. Symphyotrichum pilosum (Willd.) Nesom (Aster pilosus Willd.)". Canadian Journal of Plant Science. 81 (4): 851–865. doi:10.4141/P00-074.

- Cockayne, L.; Allan, H.H. (30 October 1926). "The naming of wild hybrid swarms". Nature. 118 (2974). London, UK: Springer Nature: 623–624. doi:10.1038/118623a0.

- CRREL (2020). "2020 National Wetland Plant List, version 3.5" (PDF). wetland-plants.usace.army.mil. Hanover, New Hampshire: US Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory. pp. 158, 331. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- Curators Herbarium B (2022). "Aster pilosus Willd. digital herbarium specimen (barcode BW15857010; image ID 391574) (Aster pilosus Willd., Sp. Pl., ed. 4 [Willdenow] 3(3): 2025 (1803))". Digital specimen images at the Herbarium Berolinense [Dataset] (ww2.bgbm.org). Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) (2022). "Rothrock State Forest Wild and Natural Areas". Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- European Commission (2 August 2022). "List of Invasive Alien Species of Union concern". ec.europa.eu. European Union. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- Freyman, W.A. (2022). "Universal FQA: Compare species coefficients". universalfqa.org. Chicago: Openlands. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

Choose 'FQA Databases', then 'Compare Species Coefficients', then enter the desired search term (usually a species name).

- Freyman, W.A.; Master, L.A.; Packard, S. (2016). "The Universal Floristic Quality Assessment (FQA) Calculator: an online tool for ecological assessment and monitoring". Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 7 (3): 380–383. doi:10.1111/2041-210X.12491.

- Gianopulos, K. (2014). Coefficient of Conservatism Database Development for Wetland Plants Occurring in the Southeast United States (Report). NC Dept. of Envir. Quality, Div. of Water Resources: Wetlands Branch. Report to the EPA. developed with 15 expert botanists. Retrieved 8 November 2022 – via Floristic Quality Assessment.

- Gray, A. (1884). Synoptical Flora of North America. Caprifoliaceae – Compositae. Vol. 1, part 2. New York: American Book Company. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.10847. LCCN 12032677. OCLC 7049357. Retrieved 20 November 2022 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Jackson, J.R.; Willemsen, R.W. (1 August 1976). "Allelopathy in the first stage of secondary succession on the piedmont of New Jersey". American Journal of Botany. 63 (7). St. Louis, Missouri: Botanical Society of America: 1015–1023. doi:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1976.tb13184.x.

- Medley, M.E. (20 April 2021). "Aster priceae and A. kentuckiensis (Asteraceae): Nomenclatural history and a new binomial for Price's aster" (PDF). Phytoneuron. 2021 (18): 1–3. ISSN 2153-733X. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- Metzler, K.; Ring, R.; Faber-Langendoen, D. (2018). "Database of coefficients of conservatism for Omernik Level 3 Ecoregion 84". www.universalfqa.org. Chicago: Openlands. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Morhardt, S.; Morhardt, E. (2004). California Desert Flowers: An Introduction to Families, Genera, and Species. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24003-0.

- National General Status Working Group (April 2022). "Standardized Common Names for Wild Species in Canada". www.wildspecies.ca (Microsoft Excel) (in English and French). Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- NatureServe (3 November 2022). "Symphyotrichum pilosum". explorer.natureserve.org. Arlington, Virginia. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- NatureServe (3 November 2022a). "Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pilosum". explorer.natureserve.org. Arlington, Virginia. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- NatureServe (3 November 2022b). "Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei". explorer.natureserve.org. Arlington, Virginia. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- NC State Extension (n.d.). "Symphyotrichum pilosum". North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox (plants.ces.ncsu.edu). Raleigh: North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Nesom, G.L. (September 1994). "Review of the taxonomy of Aster sensu lato (Asteraceae: Astereae), emphasizing the New World species". Phytologia. 77 (3). Huntsville, Texas: Michael J. Warnock (published 31 January 1995): 141–297. ISSN 0031-9430. Retrieved 24 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Northern Great Plains Floristic Quality Assessment Panel (2017). "Dakotas, 2017 [updated from Coefficients of conservatism for the vascular flora of the Dakotas and adjacent grasslands; U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Information and Technology Report USGS/BRD/ITR-2001-0001]". www.universalfqa.org. Chicago: Openlands. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

Updated the nomenclature by comparing to ITIS on the 2001 list and removed duplicates.

- Picton, P. (1999). The Gardener's Guide to Growing Asters. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc. ISBN 0-88192-473-3. OCLC 715820196.

- POWO (2022). "Symphyotrichum pilosum (Willd.) G.L.Nesom". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- POWO (2022a). "Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pilosum". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- POWO (2022b). "Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- POWO (2022c). "Oligoneuron album (Nutt.) G.L.Nesom". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- POWO (2022d). "Oligoneuron riddellii (Frank) Rydb". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- POWO (2022e). "Solidago decemflora DC". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- POWO (2022f). "Oligoneuron ohioense (Riddell) G.N.Jones". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- POWO (2022g). "Liatris aspera var. intermedia (Lunell) Gaiser". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- POWO (2022h). "Lithospermum croceum Fernald". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- POWO (2022i). "Symphyotrichum × priceae (Britton) G.L.Nesom". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- Rothrock, P.E. (June 2004). Floristic quality assessment in Indiana: the concept, use, and development of coefficients of conservatism. Final report for ARN A305-4-53, EPA Wetland Program Development Grant CD975586-01 (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- Royal Horticultural Society (n.d.a). "RHS Plant Finder - Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei". www.rhs.org.uk. London: Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Royal Horticultural Society (n.d.b). "RHS Plant Finder - Symphyotrichum 'Ochtendgloren' (pilosum var. pringlei hybrid)". www.rhs.org.uk. London: Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Royal Horticultural Society (n.d.c). "RHS Plant Finder - Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei double flowered". www.rhs.org.uk. London: Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Royal Horticultural Society (n.d.d). "RHS Plant Finder - Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei 'Monte Cassino'". www.rhs.org.uk. London: Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Royal Horticultural Society (n.d.e). "RHS Plant Finder - Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei 'October Glory'". www.rhs.org.uk. London: Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Royal Horticultural Society (n.d.f). "RHS Plant Finder - Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei 'Phoebe'". www.rhs.org.uk. London: Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Royal Horticultural Society (n.d.g). "RHS Plant Finder - Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei 'Pink Cushion'". www.rhs.org.uk. London: Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Royal Horticultural Society (July 2017). "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). www.rhs.org.uk. London: Royal Horticultural Society. p. 95. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- Semple, J.C. (29 January 2014). "Symphyotrichum pilosum". www.uwaterloo.ca. Ontario. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- Semple, J.C. (29 January 2014a). "Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pilosum". www.uwaterloo.ca. Ontario. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- Semple, J.C. (29 January 2014b). "Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pringlei". www.uwaterloo.ca. Ontario. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- Semple, J.C. (30 January 2014c). "Symphyotrichum subsect. Porteriani". www.uwaterloo.ca. Ontario. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- Semple, J.C.; Heard, S.B.; Brouillet, L. (2002). "Cultivated and Native Asters of Ontario (Compositae: Astereae)". University of Waterloo Biology Series. 41. Ontario: Department of Biology, University of Waterloo: 1–134. ISSN 0317-3348.

- Skevington, J.H.; Locke, M.M.; Young, A.D.; Moran, K.; Crins, W.J.; Marshall, S.A. (2019). Field Guide to the Flower Flies of Northeastern North America. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691189406.

- United States National Herbarium (29 August 2016). "Aster ericoides var. pringlei A.Gray digital herbarium specimen (barcode 00145617) (Gray, A. 1884. Syn. Fl. N. Amer. 1: 184)". www.si.edu. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- USDA, NRCS (2014). "Symphyotrichum pilosum". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- USDA, NRCS (2014a). "Carex richardsonii". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- USDA, NRCS (2014b). "Carex tetanica". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- USDA, NRCS (2014c). "Eleocharis elliptica". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- USDA, NRCS (2014d). "Oenothera clelandii". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- USDA, NRCS (2014e). "Artemisia campestris subsp. caudata". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- USDA, NRCS (2014f). "Oenothera clelandii". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- VanDyk, J., ed. (2021). BugGuide.Net: Identification, Images, and Information for Insects, Spiders and their Kin for the United States and Canada. Ames: Iowa State University.

- Weakley, A.S. (2022). "Symphyotrichum kentuckiense (Britton) Medley". Flora of the Southeastern United States (fsus.ncbg.unc.edu). North Carolina Botanical Garden. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- Wilhelm, G.; Rericha, L. (2017). Flora of the Chicago Region: A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis. Illustrated by Lowther, M.M. Indianapolis: Indiana Academy of Science. ISBN 978-1883362157. OCLC 983207050.

- Willdenow, C.L. (1803). Species Plantarum, 4th edition (in Latin). Vol. 3, part 3. Berlin: G.C. Nauk. pp. [1477]–2409. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.37657. LCCN ca07002380. OCLC 5251202. Retrieved 20 November 2022 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Yatskievych, G., ed. (9 July 2009). "Symphyotrichum pilosum". Flora of Missouri. Missouri Botanical Garden. Archived from the original on 6 November 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2022 – via Tropicos.org.