This article duplicates the scope of other articles, specifically Schools of Islamic theology. (June 2016) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2015) |

- See Islamic theology for Islamic schools of divinity; see Aqidah for the concept of the different "creeds" in Islam; see Ilm al-Kalam for the concept of theological discourse.

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

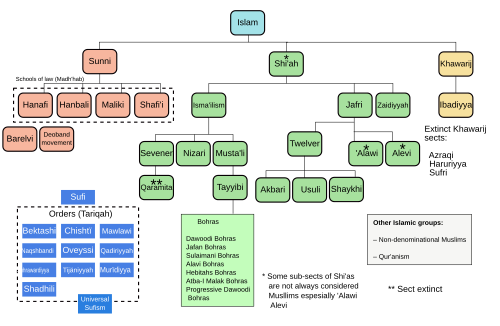

This article summarizes the different branches and various types of schools in Islam. There are three types of schools in Islam: Schools of Islamic jurisprudence, Islamic schools of Sufism better known as Tasawwufī-tārīqat and Aqidah schools of Islamic divinity. While all branches recognize the Qur'an, they differ in which other authorities they acknowledge.

This article also summarizes Islamism – the view that Islam is also a political system – and Liberal movements within Islam based on Ijtihad or interpretation of the scriptures.

Islamic denominations edit

In the beginning Islam was divided into three major sects. These political divisions are well known as Sunni, Shi'a and Kharijites. Each sect developed several distinct jurisprudence system reflecting their own understanding of the Islamic law during the course of the History of Islam. For instance, Sunnis are separated into five sub-sects, namely, Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanbalites and Ẓāhirī. Shi'a, on the other hand, was first developed Kaysanites and in turn divided into three major branches known as Fivers, Seveners and Twelvers. Qarmatians, Ismailis, Fatimids, Assassins of Alamut and Druses were all emerged from the Seveners.[2] Isma'ilism later split into Nizari Ismaili and Musta’li Ismaili, and then Mustaali was divided into Hafizi and Taiyabi Ismailis.[3] Moreover, Imami-Shi'a later brought into existence Ja'fari jurisprudence. Akhbarism, Usulism, Shaykism, Alawites[4] and Alevism[5] were all developed from Ithna'asharis.[6] Similarly, Khawarij was initially divided into five major branches as Sufris, Azariqa, Najdat, Adjarites and Ibadis. Among these numerous branches, only Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanbali, Imamiyyah-Ja'fari-Usuli, Nizārī Ismā'īlī, Alevi,[7] Zaydi, Ibadi, Zahiri, Alawite,[8] Druze and Taiyabi communities have survived. In addition, some new schools of thought and movements like Quranist Muslims, Ahmadi Muslims and African American Muslims were later emerged independently.[9]

Sunni Islam edit

| Part of a series on Sunni Islam |

|---|

| Islam portal |

Sunni Muslims are the largest denomination of Islam and are known as Ahl as-Sunnah wa’l-Jamā‘h or simply as Ahl as-Sunnah. The word Sunni comes from the word sunnah, which means the teachings and actions or examples of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad. Therefore, the term "Sunni" refers to those who follow or maintain the sunnah of Muhammad. In many countries, overwhelming majorities of Muslims are Sunnis, so that they simply refer to themselves as "Muslims" and do not use the Sunni label.

The Sunnis believe that Muhammad did not specifically appoint a successor to lead the Muslim ummah (community) before his death, and after an initial period of confusion, a group of his most prominent companions gathered and elected Abu Bakr Siddique, Muhammad's close friend and a father-in-law, as the first caliph of Islam. Sunni Muslims regard the first four caliphs (Abu Bakr, `Umar ibn al-Khattāb, Uthman Ibn Affan and Ali ibn Abu Talib) as "al-Khulafā’ur-Rāshidūn" or "The Rightly Guided Caliphs." Sunnis also believe that the position of caliph may be attained democratically, on gaining a majority of the votes, but after the Rashidun, the position turned into a hereditary dynastic rule because of the divisions started by the Umayyads and others. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1923, there has never been another caliph as widely recognized in the Muslim world.

Schools of Sunni jurisprudence edit

Madhhab is an Islamic term that refers to a school of thought or religious jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. Several of the Sahaba had a unique school of jurisprudence, but these schools were gradually consolidated or discarded so that there are currently four recognized schools. The differences between these schools of thought manifest in some practical and philosophical differences. Sunnis generally do not identify themselves with a particular school of thought, simply calling themselves "Muslims" or "Sunnis," but the populations in certain regions will often - whether intentionally or unintentionally - follow the views of one school while respecting others.

Hanafi edit

The Hanafi school was founded by Abu Hanifa an-Nu‘man. It is followed by Muslims in the Levant, Central Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Western Lower Egypt, Iraq, Turkey, the Balkans and by most of Russia's Muslim community. There are movements within this school such as Barelvis and Deobandi. They are concentrated in South Asia and in most parts of India.

Maliki edit

The Maliki school was founded by Malik ibn Anas. It is followed by Muslims in North Africa, Western Africa, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, in parts of Saudi Arabia and in Upper Egypt. The Murabitun World Movement follows this school as well. In the past, it was also followed in parts of Europe under Islamic rule, particularly Islamic Spain and the Emirate of Sicily.

Shafiʿi edit

The Shafiʿi school was founded by Muhammad ibn Idris ash-Shafiʿi. It is followed by Muslims in Saudi Arabia, Eastern Lower Egypt, Indonesia, Jordan, Palestine, the Philippines, Singapore, Somalia, Thailand, Yemen, Kurdistan, and the Mappilas of Kerala and Konkani Muslims of India. It is the official school followed by the governments of Brunei and Malaysia.

Hanbali edit

The Hanbali school was founded by Ahmad ibn Hanbal. It is followed by Muslims in Qatar, most of Saudi Arabia and minority communities in Syria and Iraq. The majority of the Salafist movement claims to follow this school.

Ẓāhirī edit

The Ẓāhirī school was founded by Dawud al-Zahiri. It is followed by minority communities in Morocco and Pakistan. In the past, it was also followed by the majority of Muslims in Mesopotamia, Portugal, the Balearic Islands, North Africa and parts of Spain.

Shia Islam edit

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

|---|

| Shia Islam portal |

Shia Islam (شيعة Shia, sometimes Shi'a; adjective "Shia"/Shi'ite), is the second-largest denomination of Islam, comprising 10-13%[10][11][12] of the total Muslim population in the world.[13] Shia Muslims, though a minority in the Muslim world, constitute the majority of the populations in Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Iran, and Iraq, as well as a plurality in Lebanon.

In addition to believing in the authority of the Qur'an and teachings of Muhammad, Shia believe that Muhammad's family, the Ahl al-Bayt (the "People of the House"), including his descendants known as Imams, have special spiritual and political authority over the community[14] and believe that Ali ibn Abi Talib, Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law, was the first of these Imams and was the rightful successor to Muhammad, and thus reject the legitimacy of the first three Rashidun caliphs.[15]

The Shia Islamic faith is broad and includes many different groups. There are various Shia theological beliefs, schools of jurisprudence, philosophical beliefs, and spiritual movements. The Shia identity emerged soon after the martyrdom of Hussain son of Ali (the grandson of Muhammad) and Shia theology developed as a result of a shift from the political to the ideological in second century Shi'ism[16] and the first Shia governments and societies were established by the end of the ninth century.

Significant Shia communities exist in the coastal regions of West Sumatra and in Aceh in Indonesia (see Tabuik). The Shia presence is negligible elsewhere in Southeast Asia, where Muslims are predominantly Shafi'i Sunnis.

A significant syncretic Shia minority is present in Nigeria, centered in the state of Kaduna (see Shia in Nigeria). East Africa holds several populations of Ismaili Shia, primarily descendants of immigrants from South Asia during the colonial period, such as the [Khoja].

According to the Shia Muslim community,[17] one of the lingering problems in estimating the Shia population is that unless the Shia form a significant minority in a Muslim country, the entire population is often listed as Sunni.[17] The reverse, however, has not held true, which may contribute to imprecise estimates of the size of each sect. For example, the 1926 rise of the House of Saud in Arabia brought official discrimination against Shia.[18] Similarly, after the forced conversion of Sunnis to Shias during the Safavids' rule, anti-Sunni sentiments and persecution have remained in Iran where they are often not allowed to pray or build mosques.[19]

Schools of Shia jurisprudence edit

Shia Islam is divided into three branches. The largest and best known are the Twelver (اثنا عشرية iṯnāʿašariyya), named after their adherence to the Twelve Imams. They form a majority of the population in Iran, Azerbaijan, Bahrain and Iraq. Other smaller branches include the Ismaili and Zaidi, who dispute the Twelver lineage of Imams and beliefs.[20]

The Twelver Shia faith is predominantly found in Iran (90%), Azerbaijan (85%), Bahrain (70%), Iraq (65%), Lebanon (40%),[21] Kuwait (25%), Albania (20%), Pakistan (25%), Afghanistan (20%).

The Zaidi dispute the succession of the fifth Twelver Imam, Muhammad al-Baqir, because he did not stage a revolution against the corrupt government, unlike Zaid ibn Ali. They do not believe in a normal lineage, but rather that any descendant of Hasan ibn Ali or Husayn ibn Ali who stages a revolution against a corrupt government is an imam. The Zaidi are mainly found in Yemen.

The Ismaili dispute the succession of the seventh Twelver Imam, Musa al-Kadhim, believing his older brother Isma'il ibn Jafar actually succeeded their father Ja'far al-Sadiq, and did not predecease him like Twelver Shia believe. Ismaili form small communities in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, India, Syria, United Kingdom, Canada, Uganda, Portugal, Yemen, China, Bangladesh and Saudi Arabia[22] and have several sub-branches.

Twelver edit

Twelvers believe in twelve Imams. The twelfth Imam is believed to be in occultation, and will appear again just before the Qiyamah (Islamic view of the Last Judgment). The Shia hadiths include the sayings of the Imams. Many Sunni Muslims criticize the Shia for certain beliefs and practices, including practices such as the Mourning of Muharram (Mätam). They are the largest Shia school of thought (93%), predominant in Azerbaijan, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon and Bahrain and have a significant population in Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, Kuwait, and the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia. The Twelver Shia are followers of either the Jaf'ari or Batiniyyah madh'habs.

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

| Twelver Shi'ism |

|---|

| Shia Islam portal |

Ja'fari jurisprudence edit

Followers of the Jaf'ari madh'hab are divided into the following sub-divisions, although these are not considered different sects:

- Usulism – The Usuli form the overwhelming majority within the Twelver Shia denomination. They follow a Marja-i Taqlid on the subject of taqlid and fiqh. They are concentrated in Iran, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, India, Iraq, and Lebanon.

- Akhbarism – Akhbari, similar to Usulis, however reject ijtihad in favor of hadith. Concentrated in Bahrain.

- Shaykhism – Shaykhism is an Islamic religious movement founded by Shaykh Ahmad in the early 19th century Qajar dynasty, Iran, now retaining a minority following in Iran and Iraq. It began from a combination of Sufi and Shia and Akhbari doctrines. In the mid 19th-century many Shaykhis converted to the Bábí and Bahá'í religions, which regard Shaykh Ahmad highly.

Batini jurisprudence edit

On the other hand, the followers of the Batiniyyah madh'hab consist of Alevis and Nusayris, who developed their own fiqh system and do not pursue the Ja'fari jurisprudence.

- Alawism

‘Alawi – Alawites are also called Nusayris, Nusairis, Namiriya or Ansariyya.[23] Their madh'hab is established by Ibn Nusayr,[24] and their aqidah is developed by Al-Khaṣībī.[25] They follow Cillī aqidah of "Maymūn ibn Abu’l-Qāsim Sulaiman ibn Ahmad ibn at-Tabarānī fiqh" of the ‘Alawis.[4][26] Slightly over one million of them live in Syria and Lebanon.[8]

- Alevism

Alevi – Alevis are sometimes categorized as part of Twelver Shia Islam, and sometimes as its own religious tradition, as it has markedly different philosophy, customs, and rituals. They have many Tasawwufī characteristics and express belief in the Qur'an and The Twelve Imams, but reject polygamy and accept religious traditions predating Islam, like Turkish shamanism. They are significant in East-Central Turkey. They are sometimes considered a Sufi sect, and have an untraditional form of religious leadership that is not scholarship oriented like other Sunni and Shia groups. They number around 24 million worldwide, of which 17 million are in Turkey, with the rest in the Balkans, Albania, Azerbaijan, Iran and Syria.

- Anatolian Qizilbashism and Alevi Islamic School of Theology

In Turkey, Shia Muslim people belong to the Ja'fari jurisprudence Madhhab, which tracks back to the sixth Shia Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq (also known as Imam Jafar-i Sadiq), are called as the Ja'faris, who belong to Twelver Shia. Although the Alevi Turks are considered a part of Twelver Shia Islam, their belief is different from the Ja'fari jurisprudence in conviction.

- "The Alevi-Turks" has a unique and perplex conviction tracing back to Kaysanites Shia and Khurramites which are considered as Ghulat Shia. According to Turkish scholar Abdülbaki Gölpinarli, the Qizilbash ("Red-Heads") of the 16th century - a religious and political movement in Azerbaijan that helped to establish the Safavid dynasty - were "spiritual descendants of the Khurramites".[27]

- Among the members of the "Qizilbash-Tariqah" who are considered as a sub-sect of the Alevis, two figures firstly Abu Muslim Khorasani who assisted Abbasid Caliphate to beat Umayyad Caliphate, but later eliminated and murdered by Caliph Al-Mansur, and secondly Babak Khorramdin who incited a rebellion against the Abbasid Caliphate and consequently was killed by Caliph al-Mu'tasim are highly respected. This belief provides strong clues about their Kaysanites Shia and Khurramites origins. In addition, the "Safaviyya Tariqah" leader Ismail I is a highly regarded individual in the belief of "Alevi-Qizilbash-Tariqah" associating them with the Imamah (Shia Twelver doctrine) conviction of the "Twelver Shi'a Islam".

- Their aqidah (theological conviction) is based upon a syncretic fiqh system called as "Batiniyya-Sufism"[2] which incorporates some Qarmatian sentiments, originally introduced by "Abu’l-Khāttāb Muhammad ibn Abu Zaynab al-Asadī",[28][29] and later developed by "Maymun al-Qāddāh" and his son "ʿAbd Allāh ibn Maymun",[30] and "Mu'tazila" with a strong belief in The Twelve Imams.

- Not all of the members believe that the fasting in Ramadan is obligatory although some Alevi-Turks performs their fasting duties partially in Ramadan.

- Some beliefs of Shamanism still are common amongst the Qizilbash Alevi-Turkish people in villages.

- On the other hand, the members of Bektashi Order have a conviction of "Batiniyya Isma'ilism"[2] and "Hurufism" with a strong belief in the The Twelve Imams.

- In conclusion, Qizilbash-Alevis are not a part of Ja'fari jurisprudence fiqh, even though they can be considered as members of different Tariqa of Shia Islam all looks like sub-classes of Twelver. Their conviction includes "Batiniyya-Hurufism" and "Sevener-Qarmatians-Ismailism" sentiments.[2][31]

- They all may be considered as special groups not following the Ja'fari jurisprudence, like Alawites who are in the class of Ghulat Twelver Shia Islam, but a special Batiniyya belief somewhat similar to Isma'ilism in their conviction.

- In conclusion, Twelver branch of Shia Islam Muslim population of Turkey is composed of Mu'tazila aqidah of Ja'fari jurisprudence madhhab, Batiniyya-Sufism aqidah of Maymūn’al-Qāddāhī fiqh of the Alevīs, and Cillī aqidah of Maymūn ibn Abu’l-Qāsim Sulaiman ibn Ahmad ibn at-Tabarānī fiqh of the Alawites,[4][32] who altogether constitutes nearly one third of the whole population of the country. (An estimate for the Turkish Alevi population varies between Seven and Eleven Millions.[33][34] Over 85% of the population, on the other hand, overwhelmingly constitute Maturidi aqidah of the Hanafi fiqh and Ash'ari aqidah of the Shafi'i fiqh of the Sunni followers.)

- The Alevi ʿaqīdah

|

Part of a series on Nizari-Ismāʿīli Batiniyya, Hurufiyya, Kaysanites and Twelver Shī‘ism |

|---|

| Islam portal |

- Some of their members (or sub-groups) claim that God takes abode in the bodies of the human-beings (ḥulūl), believe in metempsychosis (tanāsukh), and consider Islamic law to be not obligatory (ibāḥa), similar to antinomianism.[6]

- Some of the Alevis criticizes the course of Islam as it is being practiced overwhelmingly by more than 99% of Sunni and Shia population.

- They believe that major additions had been implemented during the time of Ummayads, and easily refuse some basic principles on the grounds that they believe it contradicts with the holy book of Islam, namely the Qu'ran.

- Regular daily salat and fasting in the holy month of Ramadan are officially not accepted by all members of Alevism.

- Furthermore, some of the sub-groups like Ishikists and Bektashis, who portrayed themselves as Alevis, neither comprehend the essence of the regular daily salat (prayers) and fasting in the holy month of Ramadan that is frequently accentuated at many times in Quran, nor admit that these principles constitute the ineluctable foundations of the Dīn of Islam as they had been laid down by Allah and they had been practised in an uninterruptible manner during the period of Muhammad.

Ismā'īlīsm edit

| Part of a series on Islam Isma'ilism |

|---|

| Islam portal |

The Ismailis and Twelvers both accept the same initial Imams from the descendants of Muhammad through his daughter Fatima Zahra and therefore share much of their early history. However, a dispute arose on the succession to the Sixth Imam, Ja'far al-Sadiq, who died in 765 CE. The Ismailis accepted Ja'far's eldest son Ismā'īl (ca. 719- ca.755) as the next Imam, whereas the Twelvers accepted a younger son, Musa al-Kazim. As of 2015[update], Ismā'īlīs are concentrated in Pakistan and other parts of South Asia. The Nizārī Ismā'īlīs, however, are also concentrated in Badakhshan (mainly, Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region of Tajikistan),[35][36] Central Asia, Russia, China, New Zealand, Afghanistan, Papua New Guinea, Syria, Australia, North America (including Canada), the United Kingdom, Bangladesh and in Africa as well.[citation needed] Their total population is around 13 to 16 million (excluding the Druze population) - nearly 1% of the overall world Muslim population - and gets closer to a total of 20 million Ismā'īlīs with the inclusion of the Druzes.

Tāiyebī Mustā'līyyah edit

Mustaali – The Mustaali group of Ismaili Muslims differ from the Nizāriyya in that they believe that the successor-Imām to the Fatimid caliph, al-Mustansir, was his younger son al-Mustaʻlī, who was made Caliph by the Fatimad Regent Al-Afdal Shahanshah. In contrast to the Nizaris, they accept the younger brother al-Mustaʻlī over Nizār as their Imam. The Bohras are an offshoot of the Taiyabi, which itself was an offshoot of the Mustaali. The Taiyabi, supporting another offshoot of the Mustaali, the Hafizi branch, split with the Mustaali Fatimid, who recognized Al-Amir as their last Imam. The split was due to the Taiyabi believing that At-Tayyib Abi l-Qasim was the next rightful Imam after Al-Amir. The Hafizi themselves however considered Al-Hafiz as the next rightful Imam after Al-Amir. The Bohras believe that their 21st Imam, Taiyab abi al-Qasim, went into seclusion and established the offices of the Da'i al-Mutlaq (الداعي المطلق), Ma'zoon (مأذون) and Mukasir (مكاسر). The Bohras are the only surviving branch of the Mustaali and themselves have split into the Dawoodi Bohra, Sulaimani Bohra, and Alavi Bohra.

- Dawoodi Bohra – The Dawoodi Bohras are a denomination of the Bohras. After offshooting from the Taiyabi the Bohras split into two, the Dawoodi Bohra and the Sulaimani Bohra, over who would be the correct dai of the community. Concentrated mainly in Pakistan and India.

- Sulaimani Bohra – The Sulaimani Bohra named after their 27th Da'i al-Mutlaq, Sulayman ibn Hassan, are a denomination of the Bohras. After offshooting from the Taiyabi the Bohras split into two, the Sulaimani Bohra and the Dawoodi Bohra, over who would be the correct dai of the community. Concentrated mainly in Yemen.

- Alavi Bohra – Split from the Dawoodi Bohra over who would be the correct dai of the community. The smallest branch of the Bohras.

- Hebtiahs Bohra – The Hebtiahs Bohra are a branch of Mustaali Ismaili Shia Islam that broke off from the mainstream Dawoodi Bohra after the death of the 39th Da'i al-Mutlaq in 1754.[citation needed]

- Atba-i-Malak – The Abta-i Malak jamaat (community) are a branch of Mustaali Ismaili Shia Islam that broke off from the mainstream Dawoodi Bohra after the death of the 46th Da'i al-Mutlaq, under the leadership of Abdul Hussain Jivaji. They have further split into two more branches, the Atba-i-Malak Badra and Atba-i-Malak Vakil.[37]

Nīzār'īyyah edit

Nizārī – The Nīzār’īyyah are the largest branch (95%) of Ismā'īlī, they are the only Shia group to have their absolute temporal leader in the rank of Imamate, which is currently invested in Aga Khan IV. Their present living Imam is Mawlānā Shah Karim Al-Husayni who is the 49th Imam. Nizārī Ismā'īlīs believe that the successor-Imām to the Fatimid caliph Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah was his elder son al-Nizār. While Nizārī belong to the "Imami jurisprudence" or Ja'fāriyya Madhab (school of Jurisprudence), believed by Shias to be founded by Imam Ja'far as-Sadiq they adhere to sumpremacy of "Kalam", in the interpretation of scripture, and believe in the temporal relativism of understanding, as opposed to fiqh (traditional legalism), which adheres to an absolutism approach to revelation.

Durziyyah edit

Druze – The Druze are a small distinct traditional religion that developed in the 11th century. It began as an offshoot of the Ismaili sect of Islam, but is unique in its incorporation of Gnostic, neo-Platonic and other philosophies. Druze are considered heretical and non-Muslims by most other Muslims because they are believed to address prayers to the Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, the third Fatimid caliph of Egypt, whom they regard as "a manifestation of God in His unity." The Druze believe that he had been hidden away by God and will return as the Mahdi on Judgement Day. Like Alawis, most Druze keep the tenets of their Faith secret, and very few details are known. They neither accept converts nor recognize conversion from their religion to another. They are located primarily in the Levant. Druze in different states can have radically different lifestyles. Some claim to be Muslim, some do not, though the Druze faith itself abides by Islamic principles.[citation needed]

Zaidiyyah edit

Zaidiyyahs historically come from the followers of Zayd ibn Ali, the great-Grandson of 'Ali b. Abi Talib. They follow any knowledgeable and upright descendant of al-Hasan and al-Husayn, and are less esoteric in focus than Twelvers and Ismailis. Zaidis are the most akin sect to Sunni Islam amongst the Shi'ite madh'habs. A great majority of them, more than Seven Million people who constitutes less than 1% of the World overall Muslim population, lives in Yemen.[38]

Ghulāt movements in history edit

Muslim groups who either ascribe divine characteristics to some figures of Islamic history (usually a member of Muhammad's family (Ahl al-Bayt)) or hold beliefs deemed deviant by mainstream Shi'i theology were called as Ghulāt.

Kharijite Islam edit

Kharijite (literally, "those who seceded") is a general term embracing a variety of Muslim sects which, while originally supporting the Caliphate of Ali, later on fought against him and eventually succeeded in his martyrdom while he was praying in the mosque of Kufa. While there are few remaining Kharijite or Kharijite-related groups, the term is sometimes used to denote Muslims who refuse to compromise with those with whom they disagree.

Ibadi edit

The major Kharijite sub-sect today is the Ibadi. The sect developed out of the 7th century Islamic sect of the Kharijites. Historians and a majority of Muslims believe that the denomination is a reformed sect of the Khawārij. Nonetheless, Ibadis see themselves as quite different from the Kharijites. Believed to be one of the earliest schools, it is said to have been founded less than 50 years after the death of Muhammad.

It is the dominant form of Islam in Oman, but small numbers of Ibadi followers may also be found in countries in Northern and Eastern Africa. The early medieval Rustamid dynasty in Algeria was Ibadi.

Ibadis usually consider non-Ibadi Muslims as unbelievers, though nowadays this attitude has highly relaxed.[citation needed] They approve of the caliphates of Abū Bakr and Umar ibn al-Khattab, whom they regard as the "Two Rightly Guided Caliphs". Specific beliefs include: walāyah, friendship and unity with the practicing true believers and the Ibadi Imams; barā'ah, dissociation and hostility towards unbelievers and sinners; and wuqūf, reservation towards those whose status is unclear. While Ibadi Muslims maintain most of the beliefs of the original Kharijites, they have rejected the more aggressive methods.[citation needed]

Extinct groups edit

The Sufris (Arabic: سفريين) were a sect of Islam in the 7th and 8th centuries, and a part of the Kharijites. They believed Sura 12 (Yusuf) of the Qur'an is not an authentic Sura. Their most important branches were the Qurrīyya and Nukkarīyya.

The Harūrīs (Arabic: الحرورية) were an early Muslim sect from the period of the Four Rightly-Guided Caliphs (632-661 CE), named for their first leader, Habīb ibn-Yazīd al-Harūrī.

The other extinct branches of the Khawarij were Azariqa, Najdat, and Adjarites.

Sufism edit

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

| Islam portal |

Sufism in Islam is represented by schools known as Tasawwufī-Ṭarīqah. Sufism is a mystical-ascetic form of Islam. It is not a sect, rather it is considered as the branch of Islamic teaching that deals with the purification of inner self. By focusing on the more spiritual aspects of religion, Sufis strive to obtain direct experience of God by making use of "intuitive and emotional faculties" that one must be trained to use.[39] Tasawwuf is regarded as a science of Islam that has always been an integral part of Orthodox Islam. In his Al-Risala al-safadiyya, Shaykh Ibn Taymiyya describes the Sufis as those who belong to the path of the Sunna and represent it in their teachings and writings.

Jurist and Hadith master Ibn Taymiyya's Sufi inclinations and his reverence for Sufis like 'Abd al-Qadir Gilani can also be seen in his hundred-page commentary on Futuh al-ghayb, covering only five of the seventy-eight sermons of the book, but showing that he considered tasawwuf essential within the life of the Islamic community.

In his commentary, Ibn Taymiyya stresses that the primacy of the Shari`a forms the soundest tradition in tasawwuf, and to argue this point he lists over a dozen early masters, as well as more contemporary shaykhs like his fellow Hanbalis, al-Ansari al-Harawi and `Abd al-Qadir, and the latter's own shaykh, Hammad al-Dabbas: The upright among the followers of the Path—like the majority of the early shaykhs (shuyukh al-salaf) such as Fudayl ibn `Iyad, Ibrahim ibn Adham, Ma`ruf al-Karkhi, al-Sari al-Saqati, al-Junayd ibn Muhammad, and others of the early teachers, as well as Shaykh Abd al-Qadir, Shaykh Hammad, Shaykh Abu al-Bayan and others of the later masters—do not permit the followers of the Sufi path to depart from the divinely legislated command and prohibition

Imam Ghazali narrates in Al-Munqidh min-al-dalal:

The vicissitudes of life, family affairs and financial constraints engulfed my life and deprived me of the congenial solitude. The heavy odds confronted me and provided me with few moments for my pursuits. This state of affairs lasted for ten years but wherever I had some spare and congenial moments I resorted to my intrinsic proclivity. During these turbulent years, numerous astonishing and indescribable secrets of life were unveiled to me. I was convinced that the group of Aulia (holy mystics) is the only truthful group who follow the right path, display best conduct and surpass all sages in their wisdom and insight. They derive all their overt or covert behaviour from the illumining guidance of the holy Prophet, the only guidance worth quest and pursuit.

Ba 'Alawiyya edit

The Ba'Alawi order was founded in 13th century in Hadramaut, Yemen by al-Faqih Muqaddam Muhammad bin Ali Ba'Alawi al-Husaini. He received his ijazah from Abu Madyan in Morocco via two of his students. This sufi order is an offshoot of Qadiriyyah. The members of this Sufi way are mainly sayyids whose ancestors hail from the valley of Hadramaut,

Bektashi edit

The Bektashi Order was founded in the 13th century by the Islamic saint Haji Bektash Veli, and greatly influenced during its fomulative period by the Hurufi Ali al-'Ala in the 15th century and reorganized by Balım Sultan in the 16th century. Because of its adherence to the Twelve Imams it is classified under Twelver Shia Islam. Bektashi are concentrated in Turkey and Albania and their headquarters are in Albania[citation needed].

Chishti edit

The Chishti Order (Persian: چشتیہ) was founded by (Khawaja) Abu Ishaq Shami ("the Syrian"; died 941) who brought Sufism to the town of Chisht, some 95 miles east of Herat in present-day Afghanistan. Before returning to the Levant, Shami initiated, trained and deputized the son of the local Emir (Khwaja) Abu Ahmad Abdal (died 966). Under the leadership of Abu Ahmad’s descendants, the Chishtiyya as they are also known, flourished as a regional mystical order. The founder of the Chishti Order in South Asia was Moinuddin Chishti.

Kubrawiya edit

The Kubrawiya order is a Sufi order ("tariqa") named after its 13th-century founder Najmuddin Kubra. The Kubrawiya Sufi order was founded in the 13th century by Najmuddin Kubra in Bukhara in modern Uzbekistan.[40] The Mongols had captured Bukhara in 1221, they committed genocide and killed nearly the whole population. Sheikh Nadjm ed-Din Kubra was among those killed by the Mongols.

Mawlawiyya edit

The Mevlevi Order is better known in the West as the "whirling dervishes".

Muridiyya edit

Mouride is a large Islamic Sufi order most prominent in Senegal and The Gambia, with headquarters in the holy city of Touba, Senegal.[41]

Naqshbandīyyā edit

The Naqshbandi order is one of the major Sufi orders of Islam. Formed in 1380, the order is considered by some to be a "sober" order known for its silent dhikr (remembrance of God) rather than the vocalized forms of dhikr common in other orders. The word "Naqshbandi" (نقشبندی) is Persian, taken from the name of the founder of the order, Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari. Some have said that the translation means "related to the image-maker", some also consider it to mean "Pattern Maker" rather than "image maker", and interpret "Naqshbandi" to mean "Reformer of Patterns", and others consider it to mean "Way of the Chain" or "Golden Chain".

The conception of Naqshbandi may require more elaboration and clarity as the explanation to this effect creating ambiguity and complicity with in it. The meanings of "Naqshbandi" is to follow the pattern of head of the former. In other words, "Naqshbandi" may be taken as "followup or like a flow chart" of practices exercised by the head of this school of thought.

Khālidīyyā edit

Khālidīyyā Sufi Order is a branch of the Naqshbandiyya Sufi Silsilat al-dhahab. It begins from the time of Khalid al-Baghdadi and continues until the time of Shaykh Ismail ash-Shirwani. Nowadays İsmailağa and İskenderpaşa jamias are the most active branches of Khālidī Ṭarīqah in Turkey.

Sülaymānīyyā edit

Sülaymānī Ṭarīqah is an offshoot of Naqshbandi Islamic Ṭarīqah founded by Sülaymān Hilmi Silistrevī in Turkey.[42] It was estimated that there were more than two million followers in Turkey in the early 1990s.[43] They are the most active branch in the private Hāfīz education in Turkey.

Haqqānīyyā edit

Haqqānīyyā Ṭarīqah is an offshoot of Naqshbandi Islamic Ṭarīqah founded by Shaykh Nazim al-Qubrusi in order to spread the Sufi teachings and the Unity of belief in God that is present in all religions and spiritual paths as announced by its official website.

Ni'matullāhī edit

The Ni'matullāhī order is the most widespread Sufi order of Persia today. It was founded by Shah Ni'matullah Wali (d. 1367), established and transformed from his inheritance of the Ma'rufiyyah circle.[44] There are several suborders in existence today, the most known and influential in the West following the lineage of Dr. Javad Nurbakhsh who brought the order to the West following the 1979 Revolution in Iran.

"Naqshbandi" does not meant for images or patterns followed by the followers of this school of thoughts. "Naqshbandi" manes the "flow chart" OR to follow the sayings and doings of former.

Nurbakshi edit

The "Noorbakshia"[45] (Arabic: ش) also called Nubakshia is an Islamic sect and the Sufi order[46][47] and way that claims to trace its direct spiritual lineage and chain (silsilah) to the Islamic prophet Muhammad, through Ali, by way of Imam Ali Al-Ridha. This order became famous as Nurbakshi after Shah Syed Muhammad Nurbakhsh Qahistani who was attached with Kubrawiya order Sufi order ("tariqa") .

Oveyssi (Uwaiysi) edit

The Oveysi (or Uwaiysi) order claim to be founded 1,400 years ago by Uwais al-Qarni from Yemen. Uways received the teachings of Islam inwardly through his heart and lived by the principles taught by him, although he had never physically met Muhammad. At times Muhammad would say of him, "I feel the breath of the Merciful, coming to me from Yemen." Shortly before Muhammad died, he directed Umar (second Caliph) and Ali (the first Imam of the Shia) to take his cloak to Uwais. "According to Ali Hujwiri, Farid ad-Din Attar of Nishapur and Sheikh Muhammad Ghader Bagheri, the first recipient of Muhammad's cloak was Uwais al-Qarni. The 'Original Cloak' as it is known is thought to have passed down the generations from the prophet Abraham to Muhammad, to Uwais al-Qarni, and so on."[48]

The Oveyssi order exists today in various forms and in different countries. According to Dr. Alan Godlas of the University of Georgia's Department of Religion, a Sufi Order or tariqa known as the Uwaysi is "very active", having been introduced in the West by the 20th century Sufi, Shah Maghsoud Angha. The Uwaysi Order is a Shi'i branch of the Kubrawiya.

Godlas writes that there are two recent and distinct contemporary branches of the Uwaysi Order in the West:

Uwaiysi Tarighat, led by Shah Maghsoud Sadegh Angha's daughter, Seyyedeh Dr. Nahid Angha, and her husband Shah Nazar Seyed Ali Kianfar. Dr. Angha and Dr. Kianfar went on to found another the International Association of Sufism (IAS) which operates in California and organizes international Sufi symposia.

Now developed into an international non-profit organization, the Oveyssi order has over five-hundred thousand students with centers spanning five continents. With the use of modern technology and reach of the internet, weekly webcasts of the order's lecture and zekr sessions are broadcast live through the order's official website.[49]

Qadiri edit

The Qadiri Order is one of the oldest Sufi Orders. It derives its name from Abdul-Qadir Gilani (1077-1166), a native of the Iranian province of Gīlān. The order is one of the most widespread of the Sufi orders in the Islamic world, and can be found in Central Asia, Turkey, Balkans and much of East and West Africa. The Qadiriyyah have not developed any distinctive doctrines or teachings outside of mainstream Islam. They believe in the fundamental principles of Islam, but interpreted through mystical experience.

Senussi edit

Senussi is a religious-political Sufi order established by Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi. Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi founded this movement due to his criticism of the Egyptian ulema. Originally from Mecca, as-Senussi left due to pressure from Wahhabis to leave and settled in Cyrenaica where he was well received.[50] Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi was later recognized as Emir of Cyrenaica[51] and eventually became King of Libya. The monarchy was abolished by Muammar Gaddafi but, a third of Libyan still claim to be Senussi.

Shadhiliyyah edit

The Shadhili is a Sufi order founded by Abu-l-Hassan ash-Shadhili. Followers (murids Arabic: seekers) of the Shadhiliyya are often known as Shadhilis.[52][53]

Suhrawardiyya edit

The Suhrawardiyya order (Arabic: سهروردية) is a Sufi order founded by Abu al-Najib al-Suhrawardi (1097–1168).

Tijaniyya edit

The Tijaniyyah order attach a large importance to culture and education, and emphasize the individual adhesion of the disciple (murīd).

Ahmadiyya Islam edit

| Part of a series on

Ahmadiyya |

|---|

The Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam was founded in India in 1889 by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who claimed to be the promised Messiah ("Second Coming of Christ") the Mahdi awaited by the Muslims and a 'subordinate' prophet to Muhammad whose job was to restore the Sharia given to Muhammad by guiding or rallying disenchanted Ummah back to Islam and thwart attacks on Islam by its opponents. The followers are divided into two groups, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community and the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for the Propagation of Islam, the former believing that Ghulam Ahmad was a non-law bearing prophet and the latter believing that he was only a religious reformer though a prophet in an allegorical sense. Ahmadis consider themselves Muslims and claim to practice the pristine form of Islam as re-established with the teachings of Ghulam Ahmad.

In many Islamic countries the Ahmadis have been defined as heretics and non-Muslim and subjected to persecution and often systematic oppression.[54]

Ahmadiyya Muslim Community edit

It originated with the life and teachings of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908), who claimed to have fulfilled the prophecies of the world's reformer during the end times, who was to herald the Eschaton as predicted in the traditions of various world religions and bring about the final triumph of Islam as per Islamic prophecy. He claimed that he was the Mujaddid (divine reformer) of the 14th Islamic century, the promised Messiah and Mahdi awaited by Muslims.[55][56][57] The adherents of the Ahmadiyya movement are referred to as Ahmadis or Ahmadi Muslims.

Ahmadis thought emphasizes the belief that Islam is the final dispensation for humanity as revealed to Muhammad and the necessity of restoring to it its true essence and pristine form, which had been lost through the centuries. Thus, Ahmadis view themselves as leading the revival and peaceful propagation of Islam.[58] The Ahmadis were among the earliest Muslim communities to arrive in Britain and other Western countries.[58]

Ahmadiyya adherents believe that God sent Ghulam Ahmad, in the likeness of Jesus, to end religious wars, condemn bloodshed and reinstitute morality, justice and peace. They believe that he divested Islam of fanatical beliefs and practices by championing what is in their view, Islam’s true and essential teachings as practised by Muhammad.[59] The Ahmadiyya Community is the larger community of the two arising from the Ahmadiyya movement and is guided by the Khalifa (Caliph), currently Khalifatul Masih V, who is the spiritual leader of Ahmadis and the successor to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. He is called the Khalifatul Masih(successor of the Messiah). .

Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement edit

The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement also known as the Lahoris, formed as a result of ideological differences within the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, after the demise of Maulana Hakim Noor-ud-Din in 1914, the first Khalifa after its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. The main dispute was based on differing interpretations of a verse [Quran 33:40] related to the finality of prophethood. Other issues of contention were the Kalima, funeral prayers, and the suitability of the elected Khalifa (2nd successor) Mirza Basheer-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad (the son of the Founder). The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement is led by a President or Emir.

New American denominations edit

African American denominations edit

Moorish Science edit

The Moorish Science Temple of America is an American organization founded in 1913 AD by Prophet Noble Drew Ali, whose name at birth was Timothy Drew. He claimed it was a sect of Islam but he also drew inspiration from Buddhism, Christianity, Gnosticism and Taoism. Its significant divergences from mainstream Islam and strong African-American ethnic character[60] make its classification as an Islamic denomination a matter of debate among Muslims and scholars of religion.

Its primary tenet was the belief that they are the ancient Moabites who inhabited the Northwestern and Southwestern shores of Africa. The organization also believes that their descendents after being conquered in Spain are slaves who were captured and held in slavery from 1779–1865 by their slaveholders.

Although often criticised as lacking scientific merit, adherents of the Moorish Science Temple of America believe that the Negroid Asiatic was the first human inhabitant of the Western Hemisphere. In their religious texts, adherents refer to themselves as "Asiatics",[61] presumably referring to the non-Mongoloid Paleoamericans (see Luzia Woman). These adherents also call themselves "indigenous Moors", "American Moors" or "Moorish Americans" in contradistinction to "African Moors" or "African Americans".

File:Nation of Islam Symbol.png Nation of Islam flag.

Nation of Islam edit

| Part of a series on the |

| Nation of Islam |

|---|

| Islam portal Politics portal |

The Nation of Islam was founded by Wallace Fard Muhammad in Detroit in 1930,[62] with a declared aim of "resurrecting" the spiritual, mental, social and economic condition of the black man and woman of America and the world. The group believes Fard Muhammad was God on earth,[62][63] a belief viewed as shirk by mainstream Muslims. It does not see Muhammad as the final prophet, but Elijah Muhammad as the "Messenger of Truth" and only allows people of black ethnicity and believes they are the original race on earth.

In 1975, the teachings were abandoned and the group was renamed the American Society of Muslims by Warith Deen Mohammed, the son of Elijah Muhammad.[64] He brought the group into mainstream Sunni Islam, establishing mosques instead of temples and promoting the Five pillars of Islam.[65][66] Thousands (estimated 2 million) of African Americans joined Imam Muhammad in mainstream Islam.[67] Some members were dissatisfied, including Louis Farrakhan, who revived the group again in 1978 with the same teachings of the previous leaders. It currently has from 30,000 to 70,000 members.[68]

Five Percenter edit

The Five-Percent Nation was founded in 1964 in the United States.

United Nation of Islam edit

United Nation of Islam was founded in 1978 by Royall Jenkins, who remained as a member of Nation of Islam until after the death of Elijah Muhammad but later split from the organization in 1978.

Aqidah schools of Islamic divinity edit

Aqidah is an Islamic term meaning "creed" or "belief". Any religious belief system, or creed, can be considered an example of aqidah. However, this term has taken a significant technical usage in Muslim history and theology, denoting those matters over which Muslims hold conviction. The term is usually translated as "theology". Such traditions are divisions orthogonal to sectarian divisions of Islam, and a Mu'tazili may for example, belong to Jafari, Zaidi or even Hanafi school of jurisprudence.

| Part of a series on Aqidah |

|---|

|

Including:

|

Kalām edit

Kalām is the Islamic philosophy of seeking theological principles through dialectic. In Arabic, the word literally means "speech/words". A scholar of kalām is referred to as a mutakallim (Muslim theologian; plural mutakallimūn). There are many schools of Kalam, the main ones being the Ash'ari and Maturidi schools in Sunni Islam.

Ash'ari edit

Ash'ari is a school of early Islamic philosophy founded in the 10th century by Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari. The Asharite view was that comprehension of the unique nature and characteristics of God were beyond human capability.

Maturidi edit

A Maturidi is one who follows Abu Mansur Al Maturidi's theology, which is a close variant of the Ash'ari school. Points which differ are the nature of belief and the place of human reason. The Maturidis state that belief (iman) does not increase nor decrease but remains static; it is piety (taqwa) which increases and decreases. The Ash'aris say that belief does in fact increase and decrease. The Maturidis say that the unaided human mind is able to find out that some of the more major sins such as alcohol or murder are evil without the help of revelation. The Ash'aris say that the unaided human mind is unable to know if something is good or evil, lawful or unlawful, without divine revelation.

Traditionalist Theology edit

Traditionalist theology, sometimes referred to as the Athari school, derives its name from the word "tradition" as a translation of the Arabic word hadith or from the Arabic word athar, meaning "narrations". The traditionalist creed is to avoid delving into extensive theological speculation. They rely on the Qur'an, the Sunnah, and sayings of the Sahaba, seeing this as the middle path where the attributes of Allah are accepted without questioning their nature (bi la kayf). Ahmad bin Hanbal is regarded as the leader of the traditionalist school of creed. The term athari has been historically synonymous with Salafi. The central aspect of traditionalist theology is its definition of Tawhid, meaning literally unification or asserting the oneness of Allah.[69][70][71][72]

Murji'ah edit

Murji'ah (Arabic: المرجئة) is an early Islamic school whose followers are known in English as "Murjites" or "Murji'ites" (المرجئون). During the early centuries of Islam, Muslim thought encountered a multitude of influences from various ethnic and philosophical groups that it absorbed. Murji'ah emerged as a theological school that was opposed to the Kharijites on questions related to early controversies regarding sin and definitions of what is a true Muslim.

They advocated the idea of "delayed judgement". Only God can judge who is a true Muslim and who is not, and no one else can judge another as an infidel (kafir). Therefore, all Muslims should consider all other Muslims as true and faithful believers, and look to Allah to judge everyone during the last judgment. This theology promoted tolerance of Umayyads and converts to Islam who appeared half-hearted in their obedience. The Murjite opinion would eventually dominate that of the Kharijites.

The Murjites exited the way of the Sunnis when they declared that no Muslim would enter the hellfire, no matter what his sins. This contradicts the traditional Sunni belief that some Muslims will enter the hellfire temporarily. Therefore, the Murjites are classified as Ahlul Bid'ah or "People of Innovation" by Sunnis, particularly Salafis.

Qadar’iyyah edit

The idea of Qadariyah, i.e. the Doctrine of Free-Will, came from a Persian named Sinbuya Asvari and his follower Ma'bad al-Juhani, both was put to death by the Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan.

Mu'tazili edit

Mu'tazili theology originated in the 8th century in al-Basrah when Wasil ibn Ata left the teaching lessons of Hasan al-Basri after a theological dispute. He and his followers expanded on the logic and rationalism of Greek philosophy, seeking to combine them with Islamic doctrines and show that the two were inherently compatible. The Mu'tazili debated philosophical questions such as whether the Qur'an was created or eternal, whether evil was created by God, the issue of predestination versus free will, whether God's attributes in the Qur'an were to be interpreted allegorically or literally, and whether sinning believers would have eternal punishment in hell.

Jabr’iyyah edit

Jahmis were the followers of the Islamic theologian Jahm bin Safwan who associate himself with Al-Harith ibn Surayj. He was an exponent of extreme determinism according to which a man acts only metaphorically in the same way in which the sun acts or does something when it sets.[73]

Bāṭen’iyyah edit

The Bāṭen’iyyah theology, was originally introduced by Abu’l-Khāttāb Muhammad ibn Abu Zaynab al-Asadī,[28][29] and later developed by Maymūn al-Qaddāh[74] and his son ʿAbd Allāh ibn Maymūn,[30] for the esoteric interpretation[2] of the Qur'an. In the history of Islam, Seveners, Qarmatians, Fatimids and Hashashins were amongst the followers of this school of divinity.

Islamism edit

| Part of a series on Islamism |

|---|

| Politics portal |

Islamism is a term that refers to a set of political ideologies, derived from various fundamentalist views, which hold that Islam is not only a religion but a political system that should govern the legal, economic and social imperatives of the state. Many Islamists do not refer to themselves as such and it is not a single particular movement. Religious views and ideologies of its adherents vary, and they may be Sunni Islamists or Shia Islamists depending upon their beliefs. Islamist groups include groups such as Al-Qaeda, the organizer of the September 11, 2001 attacks and perhaps the most prominent; and the Muslim Brotherhood, the largest and perhaps the oldest. Although violence is often employed by some organizations, most Islamist movements are nonviolent.

Wahhabism edit

The Wahhabi movement was recently revived by the 18th century teacher Sheikh Muhammad ibn Abd-al-Wahhab in the Arabian peninsula, and was instrumental in the rise of the House of Saud to power. The terms "Wahhabi movement" and "Salafism" are often used interchangeably, although the word "Wahhabi" is specific for followers of Muhammad ibn Abd-al-Wahhab. The works of scholars like Ibn Taymiyya, Ibn al Qayyim and Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab are used for religious guidance. [75] Critics claim that Muslim Terrorism is the direct offshoot of the fanatical Islamic cult known as Wahabism, which runs Mecca and believes in the destruction of non Islamic cultures and is financed by Saudi Arabia.[76]

Ahl al-Hadith edit

The Ahl al-Hadith is a movement started in the mid-nineteenth century in Northern India. It refers to the adherent's belief that they are not bound by taqlid (as are Ahl al-Rai, literally "the people of rhetorical theology"), but consider themselves free to seek guidance in matters of religious faith and practices from the authentic hadith which, together with the Qur'an, are in their view the principal worthy guide for Muslim.[77][78] Followers call themselves Ahl al-Hadith or Salafi. The term Ahl al-Hadith is often used interchangeably with the term Wahhabi,[79] or as a branch of the latter movement,[80][81] though the movement itself claims to be distinct from Wahhabism.[82]

Political movements edit

Al-Ikhwan Al-Muslimun edit

The Al-Ikhwan Al-Muslimun, or Muslim Brotherhood, is an organisation that was founded by Egyptian scholar Hassan al-Banna, a graduate of Dar al-Ulum. With its various branches, it is the largest Sunni movement in the Arab world, and an affiliate is often the largest opposition party in many Arab nations. The Muslim Brotherhood is not concerned with theological differences, accepting Muslims of any of the four Sunni schools of thought. It is the world's oldest and largest Islamist group. Its aims are to re-establish the Caliphate and in the mean time push for more Islamisation of society. The Brotherhood's stated goal is to instill the Qur'an and sunnah as the "sole reference point for... ordering the life of the Muslim family, individual, community... and state".[citation needed]

Jamaat-e-Islami edit

The Jamaat-e-Islami is an Islamist political party in the Indian Subcontinent. It was founded in Lahore, British India, by Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi in 1941 and is the oldest religious party in Pakistan and India. Today, sister organizations with similar objectives and ideological approaches exist in India (Jamaat-e-Islami Hind), Bangladesh (Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh), Kashmir (Jamaat-e-Islami Kashmir),and Sri Lanka, and there are "close brotherly relations" with the Islamist movements and missions "working in different continents and countries", particularly those affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood or Akhwan-al-Muslimeen. The JI envisions an Islamic government in Pakistan and Bangladesh governing by Islamic law. It opposes Westernization—including secularization, capitalism, socialism, or such practices as interest based banking, and favours an Islamic economic order and Caliphate. [citation needed]

Jamaat-al-Muslimeen edit

The Jamaat ul-Muslimeen is a movement in Sunni Islam revived by the Imam Syed Masood Ahmad in the 1960s.[83] The present leader of this group is Muhammad Ishtiaq.[84]

Revivalists edit

Salafi movement edit

| Part of a series on:

Salafi movement |

|---|

| Islam portal |

The teachings of the reformer Abd Al-Wahhab are more often referred to by adherents as Salafi, that is, "following the forefathers of Islam." This branch of Islam is often referred to by others as "Wahhabi," a term that many adherents to this tradition do not use. Members of this form of Islam call themselves Muwahideen[85] ("Unitarians", or "unifiers of Islamic practice"). Salafism is a puritanical and legalistic Islamic movement and is the dominant creed in Saudi Arabia. The Salafi sect[86] is a group who believe themselves the only correct interpreters of the Koran, consider moderate Muslims to be infidels, seek to convert all Muslims to their way of thinking and to insure that its own fundamentalist version of Islam will dominate the world.[87] Traditional Sunni Sufis who oppose the movement classify it as movement of only thirty years old, and as the modern outgrowth of a two-century old heresy spawned by a scholar of the Najd area in the Eastern part of the Arabian peninsula by the name of Muhammad ibn `Abd al- Wahhab.[88]

Most of the violent terrorist groups come from the Salafi movement and their sub groups. In recent years, the Salafi doctrine has often been correlated with the jihad of terrorist organizations such as Al Qaeda and those groups in favor of killing innocent civilians.[89][90][91]

Quranism edit

Quranism (Arabic: قرآنيون Quraniyoon) is an Islamic branch that holds the Qur'an to be the only canonical text in Islam. Quranists reject the religious authority of Hadith and often Sunnah, libraries compiled by later scholars who catalogued narratives of what the Muhammad is reported to have said and done. This is in contrast to orthodox Muslims, Shias and Sunnis, who consider hadith essential for the Islamic faith.[92]

Ahle Qur'an edit

"Ahle Qur'an" is an organisation formed by Abdullah Chakralawi,[93][94] rely entirely on the chapters and verses of the Qur'an.

Submitters edit

The United Submitters International (USI) is a branch of Quranism, founded by Rashad Khalifa. Submitters considers themselves to be adhering to "true Islam", but prefer not to use the terms "Muslim" or "Islam", instead using the English equivalents: "Submitter" or "Submission". Submitters consider Khalifa to be a Messenger of God. Specific beliefs of the USI include: the dedication of all worship practices to God alone, upholding the Qur'an alone with the exception of two rejected Qur'an verses,[95] and rejecting the Islamic traditions of hadith and sunnah attributed to Muhammad. The main group attends "Masjid Tucson"[96] in Arizona, USA.

Others edit

Gülen movement edit

The Hizmet movement, established in the 1970s as an offshoot of the Nur Movement[97] and led by the Turkish Islamic scholar and preacher Fethullah Gülen in Turkey, Central Asia, and in other parts of the world, is active in education, with private schools and universities in over 180 countries as well as with many American charter schools operated by followers. It has initiated forums for interfaith dialogue.[98][99] The Cemaat movement's structure has been described as a flexible organizational network.[100] Movement schools and businesses organize locally and link themselves into informal networks.[101] Estimates of the number of schools and educational institutions vary widely; it appears there are about 300 Gülen movement schools in Turkey and over 1,000 schools worldwide.[102][103]

Fethullah Gülen advocates cooperation between followers of different religions as well as between those practicing different forms of Islam such as Alevi and Sunni in Turkey. Gülen-movement participants have founded a number of institutions across the world that claim to promote interfaith and intercultural dialogue activities. Among them the major ones are the Istanbul-based Journalists and Writers Foundation, the Washington, D.C.-based Rumi Forum, and the New Delhi-based Indialogue Foundation. In addition, in 2004 a diverse group of Gülen-movement academics founded the London Centre for Social Studies (LCSS) to generate thinking and debate amongst academics, activists, policy makers, practitioners, media and civil-society organisations both at the national and international level. As a non-profit independent research organisation, LCSS uses social-science research tools to address major social, political and economic issues such as migration, social cohesion, subjectivity, education, gender, human rights in a critical way.

Liberal Muslims edit

Liberal and progressive movements have in common a religious outlook which depends mainly on Ijtihad or re-interpretations of scriptures. Liberal Muslims & thought have lead to the birth of certain small denominations from primarily unaffiliated followers who believe in greater autonomy of the individual in interpretation of scripture, a critical examination of religious texts, gender equality, human rights, LGBT rights and a modern view of culture, tradition, and other ritualistic practices in Islam.[citation needed]

Mahdavia edit

Mahdavia (Arabic: مهدوي mahdawi) or Mahdavism, is a Mahdiist Muslim sect founded by Syed Muhammad Jaunpuri in India in the late 15th century. Jaunpuri declared himself to be Imam Mahdi at the holy city of Mecca, right in front of the Kaaba (between rukn and maqam) in the Hijri year 901 (10th Hijri), and is revered as such by Mahdavia community and Zikri Mahdavis in Balochistan.

Mahdavia was emerged as a consequence of Jaunpuri's declaration of himself to be the Hidden Twelfth Imam of the Ithnā‘ashariyyah madhhab, the prophesied redeemer in Ithnā‘ashariyyah Shia Islam, while on a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1496 (AH 901), in a similar fashion to Báb-Siyyid `Alí Muḥammad Shírází's declaration of Bábí faith at the Kaaba.[104] The Mahdavi regard Jaunpuri as the Imam Mahdi, the Caliph of Allah and the second most important figure after the Islamic Muhammad. Both the prophet and imam are considered to be masum (معصوم "infallible")[105] Mahdavis follow the doctrine of Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat.They strictly adhere to the five pillars of Islam. About five million Mahdavis populated in Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan, and also in the Pakistani provinces of Sindh and Balochistan.

Zikri Mahdavis edit

Zikri Mahdavis, or Zikris, are an offshoot of the Mahdavi movement found mostly in the Balochistan region of western Pakistan.[106] Zikri derives from the Arabic word dhikr, meaning "remembrance, devotion, invocation". The Zikri is claimed to be based around the teachings of Muhammad Jaunpuri. In religious practice, the Zikris differ greatly from mainstream Muslims and the Mahdavis. A main misconception that Zikris perform prayers called dhikr five times a day is a major one, in which sacred verses are recited, as compared to the orthodox practice of salat. Most Zikris live in Balochistan, but a large number also live in Karachi, the Sindh interior, Oman and Iran.

Non-denominational Islam edit

Non-denominational Muslims is an umbrella term that has been used for and by Muslims who do not belong to or do not self-identify with a specific Islamic denomination.[107][108][109][110]

Tolu-e-Islam edit

Tolu-e-Islam ("Resurgence of Islam") is a non-denominational Muslim organization based in Pakistan, with members throughout the world.[111] The movement was initiated by Ghulam Ahmed Pervez.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Note: Reader should be aware of the fact that Ja'fari, 'Alawi and Alevi need to be classified under Twelvers.

- ^ a b c d e Halm, H. "BĀṬENĪYA". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ Öz, Mustafa, Mezhepler Tarihi ve Terimleri Sözlüğü (The History of madh'habs and its terminology dictionary), Ensar Publications, İstanbul, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Muhammad ibn Āliyy’ūl Cillī aqidah" of "Maymūn ibn Abu’l-Qāsim Sulaiman ibn Ahmad ibn at-Tabarānī fiqh" (Sūlaiman Affandy, Al-Bākūrat’ūs Sūlaiman’īyyah - Family tree of the Nusayri Tariqat, pp. 14-15, Beirut, 1873.)

- ^ "Alevi İslam Din Hizmetleri Başkanlığı". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ a b Halm, Heinz (2004-07-21). Shi'ism. Edinburgh University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-7486-1888-0.

- ^ Alevi-Islam Religious Services - The message of İzzettin Doğan, Zafer Mah. Ahmet Yesevi Cad. No: 290, Yenibosna / Istanbul, Turkey.

- ^ a b John Pike. "Alawi Islam". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ The Amman Message summary - Official website

- ^ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Shīʿite". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ^ "Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. October 7, 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ Miller, Tracy, ed. (October 2009). Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population (PDF). Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ^ Corbin (1993), pp. 45–51

- ^ Tabatabaei (1979), pp. 41–44

- ^ Dakake (2008), pp.1 and 2

- ^ a b "Shi'ah Islamists". Islamic Harmonisation. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ^ Jean Shaoul (8 October 2001). "US war drive threatens to destabilise Saudi Arabia - World Socialist Web Site". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Saeed Kamali Dehghan (31 August 2011). "Sunni Muslims banned from holding own Eid prayers in Tehran". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ Tabatabae (1979), p. 76

- ^ "Wilson Quarterly". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ International Crisis Group. The Shiite Question in Saudi Arabia, Middle East Report N°45, 19 September 2005

- ^ "NOṢAYRIS". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ "MOḤAMMAD B. NOṢAYR". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ "ABU ʿABD-ALLĀH ḤOSAYN B. ḤAMDĀN AL-JONBALĀNI, AL-ḴAṢIBI". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Both Muhammad ibn Āliyy’ūl Cillī and Maymūn ibn Abu’l-Qāsim’at-Tabarānī were the murids of "Al-Khaṣībī", the founder of the Nusayri tariqat.

- ^ Roger M. Savory (ref. Abdülbaki Gölpinarli), Encyclopaedia of Islam, "Kizil-Bash", Online Edition 2005

- ^ a b "ABU'L-ḴAṬṬĀB ASADĪ". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ a b "ḴAṬṬĀBIYA". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ a b "ʿABDALLĀH B. MAYMŪN AL-QADDĀḤ". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Öztürk, Yaşar Nuri, En-el Hak İsyanı (The Anal Haq Rebellion) – Hallâc-ı Mansûr (Darağacında Miraç - Miraç on Gallows), Vol 1 and 2, Yeni Boyut, 2011.

- ^ Both Muhammad ibn Āliyy’ūl Cillī and Maymūn ibn Abu’l-Qāsim’at-Tabarānī were the murids of "Al-Khaṣībī", the founder of the Nusayri tariqa.

- ^ "Religions". CIA World Factbook.

- ^ "Mapping the Global Muslim Population". Pew Research Center. 7 October 2009.

- ^ Suhrobsho Davlatshoev (2006). "The Formation and Consolidation of Pamiri Ethnic Identity in Tajikistan. Dissertation" (PDF). School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University, Turkey (M.S. thesis). Retrieved 25 August 2006.

- ^ "Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) :: Regions of Tajikistan". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Islamic Voice

- ^ "Library of Congress - Federal Research Division, Country Profile: Yemen, August 2008" (PDF). Approximately 30 percent belong to the Zaydi sect of Shia Islam, and about 70 percent follow the Shafii school of Sunni Islam.

- ^ Trimingham (1998), p. 1

- ^ "Saif ed-Din Bokharzi & Bayan-Quli Khan Mausoleums". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Mourides Celebrate 19 Years in North America" by Ayesha Attah. The African magazine. (n.d.) Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ^ Barry Rubin (2010), Guide to Islamist Movements, M.E. Sharpe. p410

- ^ Banu Eligür (2010), The Mobilization of Political Islam in Turkey, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). The Garden of Truth. New York, NY: HarperCollins. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-06-162599-2.

- ^ "Sufia Noorbakhshia". Sufia Noorbakhshia. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Aggarwal, Ravina. Beyond Lines of Control: Performance and Politics on the Disputed.

- ^ Kumar, Raj (2008). Encyclopaedia Of Untouchables : Ancient Medieval And Modern. p. 345.

- ^ Dr. Ronald Grisell (1983). Sufism. Ross Books. pp. 23. ISBN 978-0-89496-038-3

- ^ "The Expansion of M.T.O. Shahmaghsoudi". MTO Shahmaghsoudi. Retrieved 2011-12-26."Through Hazrat Pir's deep commitment to his father's wish, the M.T.O. Shahmaghsoudi, School of Islamic Sufism, which he now leads, has developed into an international non-profit organization with over 500,000 students who attend centers located throughout five continents in America, Europe, Australia, Africa and Asia."

- ^ Metz, Helen Chapin. "The Sanusi Order". Libya: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ A. Del Boca, "Gli Italiani in Libia - Tripoli Bel Suol d'Amore" Mondadori 1993, p. 415

- ^ "Hazrat Sultan Bahu". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ "Home - ZIKR". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ "Localising Diaspora: the Ahmadi Muslims and the problem of multi-sited ethnography". Association of Social Anthropologists, 2004 conference panel.

- ^ Naeem Osman Memon (1994). Claims of Hadhrat Ahmad. Islam International Publications. ISBN 1-85372-552-8.

- ^ B.A Rafiq (1978). Truth about Ahmadiyyat, Reflection of all the Prohets. London Mosque. ISBN 0-85525-013-5.

- ^ Mirza Tahir Ahmad (1998). Revelation Rationality Knowledge and Truth, Future of Revelation. Islam International Publications. ISBN 1-85372-640-0.

- ^ a b "The Ahmadi Muslim Community, Who are they?". The Times. 27 May 2008.

- ^ "An Overview". Alislam.org. Retrieved 2012-11-14.

- ^ "The Aging of the Moors". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ The Holy Koran of the Moorish Science Temple of America Chapter XXV - "A Holy Covenant of the Asiatic Nation"

- ^ a b Milton C. Sernett (1999). African American religious history: a documentary witness. Duke University Press. pp. 499-501.

- ^ Elijah Muhammad. History of the Nation of Islam. BooksGuide (2008). pp. 10.

- ^ Richard Brent Turner (2004-08-25) Mainstream Islam in the African-American Experience Muslim American Society. Retrieved on 2009-06-22.

- ^ Evolution of a Community, WDM Publications, 1995.

- ^ Lincoln, C. Eric. (1994) The Black Muslims in America, Third Edition, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company) page 265.

- ^ Rosemary Skinner Keller, Rosemary Radford Ruether, Marie Cantlon (2006). Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America. Indiana University Press. pp. 752. ISBN 0-253-34685-1, ISBN 978-0-253-34685-8

- ^ 2008-02-14 "America's black Muslims close a rift" Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved on 2009-06-22.

- ^ Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyah, Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyah (1991). Tariq al-hijratayn wa-bab al-sa'adatayn. Dar al-Hadith (1991). p. 30.

- ^ al-Hanafi, Imam Ibn Abil-'Izz. Sharh At Tahawiyya. p. 76.

- ^ al-Safarayni, Muhamad bin Ahmad. Lawami' al-anwar al-Bahiyah. Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyah. p. 1/128.

- ^

Abd al-Wahhab, ibn Abd Allah, Ibn, Sulayman (1999). Taysir al-'Aziz al-Hamid fi sharh kitab al-Tawhid. 'Alam al-Kutub. pp. 17–19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ P. W. Pestman, Acta Orientalia Neerlandica: Proceedings of the Congress of the Dutch Oriental Society Held in Leiden on the Occasion of Its 50th Anniversary, 8th-9th May 1970, p 85.

- ^ Öz, Mustafa, Mezhepler Tarihi ve Terimleri Sözlüğü (The History of madh'habs and its terminology dictionary), Ensar Yayıncılık, İstanbul, 2011. (This is the name of the trainer of Muhammad bin Ismā‘īl as-ṣaghīr ibn Jā’far. He had established the principles of the Bāṭen’iyyah Madh'hab, later.

- ^ Imam Ibn Abdul Wahhab on Sufism

- ^ Brigadier V P Malhotra (Retd) (14 July 2011). Terrorism and Counter Terrorism in South Asia and India: A Case of India and her neighbours. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-93-82573-38-8.

- ^ The Columbia World Dictionary of Islamism - Olivier Roy, Antoine Sfeir - Google Books. Books.google.com.my. 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ Understanding Islam: The First Ten Steps - C. T. R. Hewer - Google Books. Books.google.com.my. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ Rabasa, Angel M. The Muslim World After 9/11 By Angel M. Rabasa, p. 275

- ^ Alex Strick Van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn, An Enemy We Created: The Myth of the Taliban-Al Qaeda Merger in Afghanistan, pg. 427. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 9780199927319

- ^ Anatol Lieven, Pakistan: A Hard Country, pg. 128. New York: PublicAffairs, 2011. ISBN 9781610390231

- ^ Guide to Islamist Movements, vol. 1, pg. 349. Ed. Barry A. Rubin. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe, 2010. ISBN 0765617471

- ^ "Why was Jamaat-ul-Muslimeen revived?". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ "Ameer-e-Jamaat-ul-Muslimeen, Muhammad Ishtiaq". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/intro/islam-salafi.htm

- ^ Have Salafis Taken Over the Muslim World and Muslim Communities, Answered by Shaykh Muhammad ibn Adam al-Kawthari, ...and only recently (in the last 30 years) has the so called Salafi sect come into existence.

- ^ http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Salafism

- ^ http://www.livingislam.org/wrt_e.html

- ^ Marc Sageman (21 September 2011). Understanding Terror Networks. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 61–. ISBN 0-8122-0679-7.

- ^ Jonathan Matusitz (16 September 2014). Symbolism in Terrorism: Motivation, Communication, and Behavior. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 172–. ISBN 978-1-4422-3579-3.

- ^ Vincenzo Oliveti (January 2002). Terror's Source: The Ideology of Wahhabi-Salafism and Its Consequences. Amadeus Books. ISBN 978-0-9543729-0-3.

- ^ "The Quranist Path". Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ^ Khalid Baig. "A Look at Hadith Rejecters' Claims". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Aboutquran.com". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Cmje". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Masjid Tucson.org: Introduction to Submission to God Alone / Islam". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Christopher L. Miller (3 January 2013). The Gülen Hizmet Movement: Circumspect Activism in Faith-Based Reform. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-1-4438-4507-6.

- ^ "The Turkish exception: Gallipoli, Gülen, and capitalism". Australia's ABC. Radio National. 31 August 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ Jenny Barbara White, Islamist Mobilization in Turkey: a study in vernacular politics, University of Washington Press (2002), p. 112

- ^ Portrait of Fethullah Gülen, A Modern Turkish-Islamic Reformist

- ^ Islam in Kazakhstan

- ^ Turkish Islamic preacher - threat or benefactor?

- ^ Turkish Schools

- ^ Balyuzi 1973, pp. 71–72

- ^ http://khalifatullahmehdi.info/books/english/Maulud.pdf

- ^ "Zikris (pronounced 'Zigris' in Baluchi) are estimated to number over 750,000 people. They live mostly in Makran and Las Bela in southern Pakistan, and are followers of a 15th-century mahdi, an Islamic messiah, called Nur Pak ('Pure Light'). Zikri practices and rituals differ from those of orthodox Islam... " Gall, Timothy L. (ed). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Culture & Daily Life: Vol. 3 - Asia & Oceania. Cleveland, OH: Eastword Publications Development (1998); pg. 85 cited after adherents.com.

- ^ Benakis, Theodoros (13 January 2014). "Islamophoobia in Europe!". New Europe. Brussels. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

Anyone who has travelled to Central Asia knows of the non-denominational Muslims – those who are neither Shiites nor Sounites, but who accept Islam as a religion generally.

- ^ Longton, Gary Gurr (2014). "Isis Jihadist group made me wonder about non-denominational Muslims". The Sentinel. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

THE appalling and catastrophic pictures of the so-called new extremist Isis Jihadist group made me think about someone who can say I am a Muslim of a non-denominational standpoint, and to my surprise/ignorance, such people exist. Online, I found something called the people's mosque, which makes itself clear that it's 100 per cent non-denominational and most importantly, 100 per cent non-judgemental.

- ^ Kirkham, Bri (2015). "Indiana Blood Center cancels 'Muslims for Life' blood drive". Retrieved 21 October 2015.

Ball State Student Sadie Sial identifies as a non-denominational Muslim, and her parents belong to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. She has participated in multiple blood drives through the Indiana Blood Center.

- ^ Pollack, Kenneth (2014). Unthinkable: Iran, the Bomb, and American Strategy. p. 29.

Although many Iranian hardliners are Shi'a chauvinists, Khomeini's ideology saw the revolution as pan-Islamist, and therefore embracing Sunni, Shi'a, Sufi, and other, more nondenominational Muslims

- ^ "Bazm-e-Tolu-e-Islam". Retrieved 15 February 2015.