This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: summarizing content. (December 2017) |

Precious Knowledge is a 2011 educational and political documentary that centers on the banning of the Mexican-American Studies (MAS) Program in the Tucson Unified School District of Arizona. The documentary was directed by Ari Luis Palos and produced by Eren Isabel McGinnis, the founders of Dos Vatos Productions.[2][3]

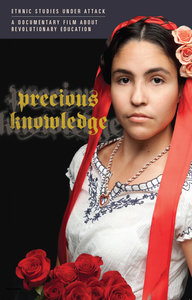

| Precious Knowledge | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Ari Luis Palos |

| Produced by | Eren Isabel McGinnis |

| Edited by | Jacob Bricca; Bill Kersey(additional editing) |

| Music by | Naïm Amor |

Production companies | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 75 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Precious Knowledge interweaves the stories of students and teachers in the Mexican-American Studies (MAS) Program, also known as "la Raza Studies", at Tucson Magnet High School. It narrates the progression of legislative backlash arguing that the program teaches "anti-American" values, proposed by the former Arizona Department of Education Superintendent of Public Instruction, Tom Horne. Proponents of the program argue that it allows students from all backgrounds to feel a connection with the history and culture of the indigenous Americas. Although the MAS Program was ultimately removed, MAS teachers and students challenged the banning at federal court. [citation needed]

Precious Knowledge received academic praise when it was screened at colleges across the country.[4] In 2011, the film won Audience Favorite and Special Jury Awards at the San Diego Latino Film Festival and Honorable Mention in the Best Documentary category at the Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival.[5] In 2012, it won Premio Mesquite for Best Documentary at the Cine Festival in San Antonio, Texas.[6]

Premiere

editThe film premiered on March 19, 2011 at the San Diego Latino Film Festival. Film producer Eren Isabel McGinnis grew up in this area and graduated from college at San Diego State University with a major in cultural anthropology. [citation needed] In addition to her personal ties with the city, McGinnis said San Diego was the perfect place to premiere the documentary due to the fact that “it’s a real important base for Chicano culture.”[7]

Plot

editThis article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (December 2017) |

The film provides insight into the controversy surrounding the Mexican-American Studies (MAS), or Raza studies, program in Tucson, Arizona. In 1997, the Tucson Unified School District's governing board unanimously voted to create a Hispanic Studies Department in all of their schools, with the goal of lowering the Latino dropout rate. The department was renamed the Mexican American/ Raza studies program in 2002 and successfully improved the achievement rates of Latinos. [citation needed] Tucson Unified School District reported that the students taking ethnic studies classes showed significant improvements on standardized tests and the graduation rate among these students averaged 93%.

The framework of the classes taught in the Raza studies program is based on a social justice pedagogy that centers around searching for the truth and the concept of love. The film takes a look inside the classroom of two Raza studies program teachers, Curtis Acosta who teaches literature, and Jose Gonzalez who teaches American Government. In their classes, Acosta and Gonzalez teach students about the history of their culture and then challenge them to reflect, realize and reconcile with their culture's past. In his article "Developing Critical Consciousness: Resistance Literature in a Chicano Literature Class," [8] Acosta asserts that it is vital for students to discover their own purpose and heritage through educational programs like that of the MAS program and persuades other educational entities to adopt similar curriculums. The program also challenge students to become “warriors for their gente,” and to take action on issues they become aware of in the classes.

Controversy arose surrounding the Raza studies program when Superintendent of schools, Tom Horne, announced that he would introduce a bill that would ban ethnic studies programs in the state of Arizona. Horne and other opponents of ethnic studies, argue that these programs promote racial divide amongst students in schools and is “in conflict with the values of American Citizenship.” Horne's bill (SB1108) initially passed through Arizona's House Appropriations Committee but didn't make it to the floor after Governor Janet Napolitano threatened to veto it, so a new bill (SB1069) to ban ethnic studies was introduced in the next legislative session. After a series of debates from both sides at the committee hearing, SB1069 passed and became scheduled for a vote before the full legislature. SB 1069 fails to pass in front of the full legislature, but lawmakers continue to challenge the program's legality; legislators propose two new bills, SB 1070 and HB 2281, which are partly aimed against the ethnic studies program.

To help decide if he would vote for HB 2281, Huppenthal accepts an invitation to Acosta's class. During class time Huppenthal engages in discourse with students and faculty about his concerns with the MAS program, at one point questioning why Benjamin Franklin is not displayed. Huppenthal thought this remark about Franklin was inappropriate. At the next Senate Education Committee voting session for the new bills, Huppenthal speaks about his experience in a MAS program class and HB 2281 is approved and sent to new Governor Jan Brewer for her signature. This leads to a student/teacher rally against HB 2281, at which the Tucson Brown Berets demonstrate their support for the MAS program. One week later, students, teachers, and community members then stage a sit-down at the state building where Horne and Dugan are holding the press conference. Four students and eleven adults are arrested for refusing to leave the state building. Despite their efforts, Governor Jan Brewer signed HB 2281 into law.

As the documentary concludes, producers film the last day of school in Acosta and Gonzalez's classes. In Acosta's class, he and the become very emotional about their year. Finally, the students are filmed at their graduation ceremony. To conclude, it is revealed that Tom Horne declared MAS program classes in violation of the law, so the TUSD cancelled the program.

Production

editAri Luis Palos and Eren Isabel McGinnis began filming Precious Knowledge on October 31, 2008, after being granted permission by the Tucson Unified School District. The filmmakers were allowed complete access to the ethnic studies program in Tucson Magnet High School throughout the 2008-2009 school year. Early on, they planned to use a combination of interviews and footage from inside and outside the MAS classrooms to explore various perspectives and further their film.[2]

Directors

editAri Luis Palos and Eren Isabel McGinnis had a long history of filming documentaries centered on minorities before embarking on this project. According to McGinnis, their films “give [a] voice to communities often silenced or stereotyped by mainstream media.”[9] McGinnis was also particularly invested in this film because she had a son attending Tucson High School during the controversy. Furthermore, both filmmakers are of Mexican descent and have a “deep reverence and love of all things Mexican”[9]

McGinnis also revealed the meaning behind the film's title in an interview that appeared in the academic journal, The Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States (MELUS).[9] "Precious knowledge" is a reference to Mayan concepts that say to "self-reflect (Tezcatlipoca), seek out precious and beautiful knowledge (Quetzalcoatl), begin to act (Huitzilopochtli) and ultimately transform (Xipe Totec)."[9] The documentary's focus on Quetzalcoatl—precious knowledge—highlights what the activists in the film are fighting for. This and other emphases on Aztec heritage throughout the film reveal the intent by the filmmakers to remind students of their own deep history and their indigenous ancestors. With this knowledge, Eren McGinnis hopes to support the same message supported by the Mexican-American Studies program that these Mexican-American students “are not ‘outsiders’ or 'invaders'” of this country.[9]

Reception

editSince its premiere on Independent Lens on May 17, 2012, the documentary is often screened at colleges across the country.[4] The screening is also sometimes accompanied by a discussion on the film with Curtis Acosta, former teacher of the MAS program in Tucson Unified School District.

- University of Pittsburgh (2018)[10]

- Texas A&M (2017)[11]

- Ferris State University (2015)[12]

- Regis University (2014)[13]

- Western Illinois University (2012)[14]

Awards

editThe film received the following awards:

- Audience Favorite and Special Jury Award, San Diego Latino Film Festival (2011)[5]

- Honorable Mention in the Best Documentary Category, Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival (2011)[5]

- Premio Mesquite for Best Documentary, Cine Festival at the Guadalupe Cultural Art Center in San Antonio, Texas (2012)[6]

After the film

editIn 2011, following the events of the film, an audit was performed by the request of John Huppenthal, in hopes of finding justifications to remove the program. However, the audit’s findings showed that the program was in line with the bill passed into law, HB 2281.[15] Despite the results of the audit, the Arizona state government informed the Tucson United School District that the school district would lose $14 million of its funding if the program were to continue. As a result, the Tucson United School District cut the Mexican-American studies (MAS) program in early 2012.[16]

Certain books taught in MAS Program classrooms were also banned from TUSD school for the same reasons used to eliminate the MAS Program. The following works were accused of presenting "anti-American" and generally racist sentiments against Americans of white European heritage.

- 500 Years of Chicano History in Pictures edited by Elizabeth Martinez

- Chicano! The History of the Mexican Civil Rights Movement by Arturo Rosales

- Critical Race Theory by Richard Delgado

- Message to Aztlan by Rodolfo Corky Gonzales

- Occupied America: A History of Chicanos by Rodolfo Acuña

- Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire

- Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, edited by Bill Bigelow and Bob Peterson.[17][18]

According to eyewitness reports by MAS students, the books were confiscated by school officials in front of students. One student noted, "We were in shock... it was very heartbreaking to see that happening in the middle of class."[19]

In March 2013, Curtis Acosta, and other teachers and students of the program took the issue to federal court.[15][20] They challenged the legality of HB 2281 and its application, with the hope that if it were overturned, the MAS program would be reinstated. The plaintiffs took issue with (1) the constitutionality of HB 2281; (2) the fact that there was no “legal justification to eliminate the Mexican-American Studies Program”, (because it was in line with the law, evidenced by the audit performed in 2011); and (3) the vague language of the law, which presented opportunity for discriminatory misinterpretation.[15] Ultimately, the federal district court left the law mostly intact. The court nullified only the section of the statute, that restricted classes "designed for a particular ethnic group," because it infringed upon the First Amendment. Unsatisfied with the results, the plaintiffs—at this point reduced to two students Korina Lopez and Maya Arce, as well as the director of the MAS program, Sean Arce (also Maya's father)—filed an appeal.[21] The case went to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit on July 7, 2015, as Arce v. Douglas. The appellate court decided to return the case to the district court to give the plaintiffs a trial on their claims of racial discrimination.[22]

On August 22, 2017, Judge A. Wallace Tashima ruled that "both enactment and enforcement [of] [HB 2281] were motivated by racial animus."[23] He further added that HB 2281 demonstrated prejudice against Latino student, thus violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[23] Judge Tashima also ruled that HB 2281 "violated students' [first] Amendment 'right to receive information and ideas.'"[23] Racist blog posts and comments from Huppenthal also influenced Judge Tashima's ruling. While he was Arizona's Superintendent, Huppenthal used the pseudonyms "Thucydides" and "Falcon 9" to speak out against the MAS Program. Huppenthal also compared the Mexican American Studies program to Hitler's regime and criticized the program's use of Spanish radio stations, billboards, TV stations, and newspapers.[24]

In an interview with Ari Bloomekatz, Curtis Acosta claimed that the court's ruling validated the MAS program, restoring the integrity of himself and his colleagues who were criticized for supporting the TUSD's ethnic studies program.[19] However, according to the Arizona Daily Star, it is unlikely that the MAS program will be reinstated. The fate of the program rests in the hands of the Tucson Unified School District Board. Since the program was eliminated, the district has been "developing 'culturally relevant courses' to replace ethnic studies programming."[25]

According to Precious Knowledge, the program served as a model in the following places: San Francisco Unified School District, Houston Independent School District, School District of Philadelphia, Los Angeles Unified School District, New Haven Unified School District, Boston Public Schools, Sacramento City Unified School District and Pomona Unified School District.[7] The large controversy and banning of the program in Arizona inspired school districts in California and Texas to consider Mexican-American Studies programs.[22] For example, the El Paso Independent School District and Ysleta Independent School District of El Paso, Texas, decided to include Mexican American Studies classes in their high schools.[26] Curtis Acosta also started a consulting business in 2013 to further spread ethnic studies classes in the states of California, Oregon, Texas, and Washington by guiding the creation, process and training of such a program in these states.[27]

Recently, several states and cities have implemented ethnic studies programs in their schools. In May 2017, Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb mandated that high schools provide at least one ethnic studies elective per year.[23] One month later, Governor Kate Brown required Oregon public schools to offer ethic studies for students in kindergarten through 12th grade and the Seattle School Board claimed they would include ethnic studies in school curriculum.[23] In October 2017, school administrators in Bridgeport, Connecticut, approved a requirement for high school graduation where students must take a half-year class on African American studies, Latin American/Caribbean studies or perspectives on race.[28][23]

References

edit- ^ "LATINO PUBLIC BROADCASTING". Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ a b Portillo, Ernesto Jr. (17 March 2011). ""Precious Knowledge:" The love and struggle of learning". Arizona Daily Star.

- ^ ""Precious Knowledge:" The love and struggle of learning". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- ^ a b "Precious Knowledge | Ethnic Studies in Arizona | Independent Lens | PBS". Independent Lens. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- ^ a b c "Precious Knowledge." Zinn Education Project. N.p., 29 Apr. 2016. Web. 16 Nov. 2016.

- ^ a b "'Granito: How to Nail a Dictator', 'Precious Knowledge' and 'El Velador' Screening at the 2012 CineFestival". Latino Public Broadcasting. Latino Public Broadcasting Community.

- ^ WILKENS, JOHN (March 17, 2011). "FILMMAKER AIMS TO TRANSCEND BORDERS; Imperial Beach native's new film to premiere at San Diego Latino Film Festival". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Acosta, Curtis (2007). "Developing Critical Consciousness: Resistance Literature in a Chicano Literature Class"(PDF). English Journal. 97.2: 36.

- ^ a b c d e Sargent, Andrew. "Building Precious Knowledge: An Interview with Documentary Filmmaker Eren Isabel McGinnis." MELUS 36.1 (2011): 195,217,243. Research Library. Web. 9 Nov. 2016.

- ^ "Film Screening: Precious Knowledge". US Official News. March 12, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "HISPANIC HERITAGE MONTH EVENTS UNDERWAY". States News Service. September 19, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "'Precious Knowledge' Film Addresses Tensions on Campus, Community". Targeted News Service. September 16, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "Diversity Dialogue: Precious Knowledge". US Official News. September 17, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "'PRECIOUS KNOWLEDGE' DOCUMENTARY MARCH 21 AT WESTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY-MACOMB, MARCH 22 IN QUAD CITIES". US Fed News. March 8, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Law School Professors Pursue Appeal of Tucson Ethnic Studies Ban." Targeted News Service. Apr. 09 2013. ProQuest. Web. 29 Oct. 2016.

- ^ "Rejected in Tucson." New York Times. 22 Jan. 2012: 12. Academic Search Premier. Web. 29 Oct. 2016

- ^ Precious Knowledge. Dir. Eren Isabel McGinnis and Ari Luis Palos. Prod. Dos Vatos Productions, Independent Television Service, Arizona Public Media, and Latino Public Broadcasting. 2011. DVD.

- ^ Reichman, Henry, ed. "Opposition Grows to Tucson Book Removals and Ethnic Studies Ban." Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom 61.2 (2012): 1-84. OmniFile Full Text Mega (H.W. Wilson). Web. 9 Nov. 2016.

- ^ a b "Outlawing Solidarity in Arizona". www.rethinkingschools.org. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- ^ "Arizona Teacher Assails Dismantling of Successful Ethnic Studies Program." Targeted News Service. 03 Oct. 2012. ProQuest. Web. 29 Oct. 2016.

- ^ Palazzolo, Joe. "Appeals Court Revives Challenge to Arizona Ban on Ethnic Studies." WSJ. Wsj.com, 7 July 2015. Web. 9 Nov. 2016.

- ^ a b "From the Bench: Schools." Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom (Online.) 64.5 (2015): 153-5. ProQuest. Web. 29 Oct. 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaleem, Jaweed (2017-08-22). "Federal judge says Arizona's ban on Mexican American studies is racially discriminatory". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- ^ Planas, Roque (2017-06-28). "Arizona Republican Details 'Eternal' Struggle Against Mexican-American Studies". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- ^ Star, Hank Stephenson Arizona Daily. "Court ruling vindicates Tucson Unified's Mexican American Studies — so what now?". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- ^ Noboa, Julio (2014-06-01). "Precious knowledge by Ari Palos (dir.)". Latino Studies. 12 (2): 310–312. doi:10.1057/lst.2014.26. ISSN 1476-3435. S2CID 145170092.

- ^ Bryson, Donna, and The A. Press. "Educators, Activists Lobby for Inclusion of Hispanic Studies in the Classroom." Monterey County Herald (California), sec. A,A: 6. March 14, 2016. Web. 9 Nov. 2016.

- ^ "Connecticut District to Require Course in Ethnic Studies for Graduation". Education Week. Retrieved 2018-05-06.