This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

Jarhead is a 2003 Gulf War memoir by author and former U.S. Marine Anthony Swofford. After leaving military service, the author went on to college and earned a double master's degree in Fine Arts at the University of Iowa.

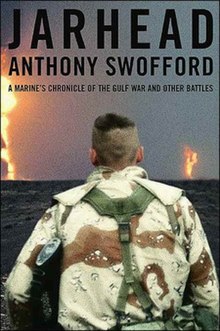

Official cover | |

| Author | Anthony Swofford |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Military |

| Publisher | Scribner |

Publication date | March 4, 2003 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 272 |

| ISBN | 0-7432-3535-5 |

| OCLC | 50598121 |

| 956.7044/245 21 | |

| LC Class | DS79.74 .S96 2003 |

Writing

editSwofford started writing the book in 1995. He stated about the writing process: "I had modest goals for my first book. I didn’t think about sales numbers or a movie option or foreign rights and invitations to international book fairs. I didn’t even know those things existed. Still heavily inhaling the fumes of pretension I’d earned at my MFA writing program, I wanted only to make art. I thought I possessed a number of unique and original insights about the making of young Marines and going to war and what combat does to a young psyche and soul. I thought that on most days I could manage to turn out a page or two of good sentences. I wrote the best book I could. I wanted my book to teach young people things about war I hadn’t been taught or hadn’t wanted to learn when I was a 17-year-old looking to escape a dull suburban life that felt like a prison."[1]

Plot

editJarhead recounts Swofford's enlistment and service in the United States Marine Corps before and during the Persian Gulf War, in which he served as a Scout Sniper Trainee with the Surveillance and Target Acquisition (STA) Platoon of 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines.

Like most of the troops stationed in the Middle East during the Gulf War, Swofford saw very little actual combat. Swofford's narrative focuses on the physical, mental, and emotional struggles of the young Marines.[2]

One of the through lines of his first-person account involves the challenge of balancing the mind-set of the warrior with one's own basic sense of humanity. Swofford admits to a sense of disappointment, frustration and emptiness that comes in the wake of ultimately being cheated of any real combat experience by a war that, for many American Marines at least, ended all too quickly after enduring many months of tedious, anticlimactic suspense. Dead Iraqi soldiers littered the desert, many having been killed by airstrikes days or weeks before Swofford and the rest of the U.S. Marine Corps invaded Kuwait.

Banning

editIn May 2023, the Hudsonville public school district in the U.S. state of Michigan removed the book from all of its school libraries.[3] One supporter of the ban stated at a school board meeting: "We're here to fight against darkness. Jarhead has an extremely violent, vulgar, pornographic diatribe, and tonight, we will learn if HPS has any intention of taking any measures to protect our students from any flagrantly obscene content."[3] An opponent of the ban stated: "We are allowing recruiters into schools where kids can sign on the dotted line, but they can't read about actual service members and soldiers experiences."[3]

In an article about the banning of his book in the Hudsonville district, Swofford wrote that most of the books banned in American schools have been by either black and/or gay authors and that: "As a straight, white male writer who has written almost exclusively about the military and warfare, I might have thought my books were safe."[1] Swofford blamed the banning of Jarhead on "MAGA intrusionists" who objected to the book's frank depiction of the daily life of U.S. Marines."[1] Swofford wrote that most of the objections to his book stemmed from the "field fuck" scene where Swofford and other Marines simulated gay sex while dressed in full protection gear from weapons of mass destruction in front of an assembled group of journalists in protest against their officers.[1] Swofford wrote that the banning of his book felt "deeply un-American" and concluded: "Make no mistake, they are banning books, but really they are restricting access to ideas. And when one small group of people ban a larger group of people access to ideas, we are in for a closing of the American mind. What begins with banning books ends with a firescape of constitutional rights ablaze."[1]

In 2023, the book was banned, in Clay County District Schools, Florida.[4]

Reception

editA review for Kirkus Reviews in 2003 wrote: "Swofford’s debut covers all the bases: a stint in basic training with a brutal drill instructor, drunken episodes with prostitutes, fights with sailors, explosions and their attendant airborne body parts, postwar trauma and depression. Yet there’s not a clichéd moment in this rueful account of a Marine’s life, in which the hazards are many and the rewards few....Extraordinary: full of insight into the minds and rucksacks of our latter-day warriors".[5] The reviewer noted that the book was not for the squeamish as Swofford recounted contracting dysentery during his time in the Middle East and how his fellow Marines mutilated the corpses of the Iraqi soldiers along the "Highway of Death".[5] The British critic Aidan Hartley wrote in his review that Jarhead was an "excellent book" about the daily life of a "jarhead" (American slang for a Marine) that told the story of the Gulf War from the vantage point of a Marine serving on the ground.[6]

In a negative review, Sam Williamson, a former Marine officer, wrote that he felt that Swofford had intentionally given an unfairly negative picture of life in the Marine Corps.[7] Williamson felt that the title of Swofford's memoir was wrong-headed as the term "jarhead" is most commonly used by other branches of the U.S. military as derogatory slang for the Marines, through he noted that within the Marine Corps the term "jarhead" is often used as an affirmative slang term.[7] Williamson felt that the picture of the all male Marine light infantry that Swoffford presented in his book as mindlessly sexist young men who made extensive use of the services of prostitutes while having troubled relationships with their wives or girlfriends was inaccurate.[7] Williamson wrote: "Now, there's no question that when you take a group of twenty-something year old boys/men, there are going to be some legendary failures in their relationships with women. Every officer and NCO spends far too much of his time providing marital counseling to troubled twenty-year olds. These problems even led a former Commandant to propose that the Marine Corps cease accepting married recruits. But that said, I also saw young marriages that were incredibly strong, and left me in awe of the commitment that existed between people so young. These relationships rate less than a paragraph in Jarhead. Yet, in contrast, there are pages and pages describing the failures that existed between women and the Marines of STA platoon."[7] Williamson felt that Swofford had focused too much on the "animalistic" side of Marine life with his tales of disgusting and/or salacious incidents, and not enough on the self-discipline needed to be a Marine.[7] Williamson concluded that the Marine Corps of the U.S. Navy are regarded as one of the premier branches of the American military, and that one would never know how this reputation was achieved from reading Jarhead.[7]

In a negative review, the former Marine Nathaniel Fick who saw action in Afghanistan and Iraq stated that he felt Swofford's writing in Jarhead was "fine", but that he hated the book, which he felt gave a distorted and dishonest picture of life in the Marine Corps.[8] Like Williamson, Fick complained about the use of the term "jarhead" as the title as he noted that Marines did not generally use that slang term to refer to themselves.[8] Fick wrote: "Swofford struck me as an ax-grinder who blamed the Corps for his own failures. He hadn’t seen enough combat to justify his angst, and conduct like his—at one point, he points a gun at another Marine and threatens to kill him—would have landed my Marines in jail."[8] However, Fick felt that the 2005 film adaption of Jarhead was much superior to the book..[8] Flck concluded: "Swofford’s war—boredom, loneliness, doubt, terror, rage, and numbness—is mostly inside his own head".[8]

In a review, the British critic Tim Adams wrote that he felt that Jarhead was over-hyped by its publishers in the United Kingdom as the book was compared to the war writings of Michael Herr, Norman Mailer, and Wilfred Owen, which he felt to be "fanciful".[9] Adams noted that unlike Herr who served as a war correspondent in Vietnam, Mailer who served in the Marine Corps in the Pacific theater of World War Two; and Owen who served in the British Army on the Western Front in World War One that Swofford never saw combat, which he felt completely undermined these comparisons.[9] Adams described Swofford as a rather naïve young man born into a military family who joined the Marine Corps at the age of 17 in 1987 as a way to find a surrogate family who came to be disillusioned by the life of a Marine.[9]

Adams noted that Swofford's principle enemy during his time in the Middle East as recounted in Jarhead was himself as he was so trapped in despair over the prospect that his girlfriend in the United States was being unfaithful to him that he seriously contemplated committing suicide.[9] Adams felt the main weakness in the book was that through Swofford was being honest in depicting the life of a Marine, but that his voice was so fractured through the prism of others that there was something superficial about the book.[9] Swofford himself wrote in Jarhead that: "The language we own is not ours. It is not a private language, but derived from Marine Corps history and lore and tactics".[9] Adams noted that most of Swofford's ideas about what military life was like was based on Vietnam war films such as Apocalypse Now and Full Metal Jacket, and that at times it felt like that Swofford was merely recycling a "script".[9] Adams concluded: "As a result, for all its show of honesty about the realities of battle, the anger at loss of life is never quite heartfelt, and the labyrinthine self-pity at the soldier's lot never quite earned. What this book brings home is that the modern soldier or, at least the modern American soldier, buttressed by overwhelming aerial firepower, is essentially a marginal figure. In the aftermath of a war he never really got to fight, Swofford suggests that 'sometimes you wish you'd killed an Iraqi'. His experience leaves him with a sense of anticlimax, of unfinished business, a hollowness that his government seems to have shared."[9]

In a highly positive review in the New York Times, the journalist Mark Bowden wrote: "Rare is the Marine who is willing to share the raw experience, and rarer still is one like Swofford-the Marine who can really write. Jarhead is some kind of classic, a bracing memoir of the 1991 Persian Gulf war that will go down with the best books ever written about military life. It is certainly the most honest memoir I have read from a participant in any recent war. Swofford writes with humor, anger and great skill. His prose is alive with ideas and feeling, and at times soars like poetry. He captures the hilarity, tedium, horniness and loneliness of the long prewar desert deployment, and then powerfully records the experience of his war."[10] In his review, Bowden noted that since the Vietnam war the Pentagon has imposed strict censorship on journalists who are expected to only put a positive gloss on the U.S. military and that likewise the men and women of the U.S. military are supposed to be always upbeat and cheerful when talking to the media.[10] Bowden wrote that the photo-op in the fall of 1990 where Swofford and his fellow Marines were told by their officers to give the most positive spin on their mission, which inspired him and the rest of Marines to engage in simulated gay sex in protest, is all too typical of the modern American military, which made Jarhead a refreshing book to read.[10] Bowden noted that Swofford was first attracted to the Marine Corps somewhat paradoxically by the 1983 suicide bombing of the Marine barracks in Beirut by the Lebanese Islamist group Hezbollah (Arabic for the "Party of Allah") that killed 241 Marines, which for him confirmed that the Marines were the most bravest and macho of all the different arms of the U.S. military.[10] At the age of 17, a recruiter for the Marine Corps told Swofford that prostitutes in the Philippines were ultra-cheap and it was possible to have a "threesome" three times a day for a mere $40 American dollars, which made Swofford "sold" on the idea of joining the Marines.[10]

Bowden noted that Swofford was different from most of the young men who join the Marines as he grew up on a military base in Japan and he was widely read and cultured, having been brought up reading books by Albert Camus, Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Homer, which gave him a broader prospective.[10] Bowden noted that Swofford like all of the other Marines in his book cared nothing for the politics of the Gulf War and for them the mere act of fighting and killing for the sake of fighting and killing was sufficient in and of itself as a motive for war.[10] In his review, Bowden noted that when Swofford learned in August 1990 that he and the rest of his unit were being sent to Saudi Arabia for a possible war with Iraq that the men of his men were cheerful at the news and celebrated with a marathon drinking bout while watching Vietnam war films.[10] Swofford stated in Jarhead that most Vietnam war films were anti-war, but for him: "Vietnam War films are all pro-war, no matter what the supposed message, what Kubrick or Coppola or Stone intended...The magic brutality of the films celebrates the terrible and despicable beauty of their fighting skills. Fight, rape, war, pillage, burn. Filmic images of death and carnage are pornography for the military man".[10] In his review, Bowden noted the most powerful passages in Jarhead dealt with Swofford's reaction to seeing the "Highway of Death" as the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy planes incinerated vast columns of Iraqi troops attempting to flee Kuwait City on the main highway leading north to Basra in February 1991.[10] Swofford felt relieved to still being alive after seeing so much death and destruction along the highway as he wrote: "The presence of so much death reminds me that I'm alive, whatever awaits me to the north. I realize I may never again be so alive. I can see everything and nothing -- this moment with the dead men has made my past worth living and my future, always uncertain, now has value".[10] Bowden noted: "His vision is unsparing and honest, and his emotions ring true...That voice isn't pretty -- it's just terribly and despicably beautiful."[10]

Film adaptations

editThe novel was adapted into a 2005 feature film of the same name starring Jake Gyllenhaal, Jamie Foxx, Peter Sarsgaard, and Lucas Black. The screenplay was written by William Broyles Jr. and the film directed by Sam Mendes. Reviews were generally positive. Jarhead 2: Field of Fire is the sequel to the 2005 film, followed by Jarhead 3: The Siege.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Swofford, Anthony (3 July 2023). "Culture Warriors Banned My Memoir About Being a Young Marine". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (2003-02-19). "BOOKS OF THE TIMES; A Warrior Haunted By Ghosts Of Battle." NYTimes.com. The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-03-08.

- ^ a b c 'Bestselling military memoir banned from Hudsonville Public Schools', WZZM (ABC-13), 22 May 2023

- ^ "District Reconsideration List". Google Docs. Retrieved 2024-09-28.

- ^ a b "Review of Jarhead". Kirkus Reviews. 15 December 2002.

- ^ Hartley, Aidan (April 2003). "The View From the Ground". Literacy Review. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Williamson, Sam (18 April 2003). "A Skewed View of Life in the Marines". FindLaw. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Fick, Nathaniel (9 November 2005). "How Accurate Is Jarhead?". Slate. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Adams, Tim (23 March 2003). "The killing machine who never actually killed". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bowden, Mark (2 March 2003). "The Things They Carried". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 January 2024.