The Xiangshuishen or Xiang River Goddesses are goddesses (or spirits and sometimes gods) of the Xiang River in Chinese folk religion. The Xiang flowed into Dongting Lake through the ancient kingdom of Chu, whose songs in their worship have been recorded in a work attributed to Qu Yuan. According to the Shanhaijing, the Xiang River deities were daughters of the supreme deity, Di. According to a somewhat later tradition, the Xiang goddesses were daughters of Emperor Yao, who were named Ehuang (Chinese: 娥皇; pinyin: É Huáng; Fairy Radiance) and Nüying (Chinese: 女英; pinyin: Nǚ Yīng; Maiden Bloom)[1] who were said to have been married by him to his chosen successor, and eventually emperor, Shun, as a sort of test of his administrative abilities: then, later, they became goddesses, after the death of their husband.

| Xiangshuishen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

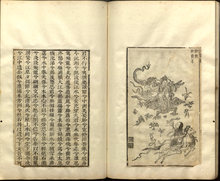

"Xiang River Goddesses" (Xiang Jun), poem number 3 of 11 in the Nine Songs section, in an annotated version of Chu Ci, published under title Li Sao, attributed to Qu Yuan and illustrated by Xiao Yuncong. | |||||||

| Chinese | 湘水神 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Xiang River Goddesses | ||||||

| |||||||

Shun's wives

editAccording to the mythological Ehuang-Nuying version, sometime in the twenty-third century BCE, before becoming divine goddesses, these two daughters of Emperor Yao were married to Shun at the planning of their father. Although later destined to be emperor and exemplar of all the virtues desirable in an emperor and exemplar for all future ages, before the marriage Shun was a simple farmer. Yao, however, was attempting to recruit worthy persons into the service of his government, the main reason being to solve the problem of the ongoing Great Flood that was devastating China. One suggestion from Yao's advisors (Four Mountains) was Shun. Yao inquired what sort of a person Shun was and decided to try him upon being told that (although a direct lineal descendant of Zhuanxu) Shun the farmer was the son of Gu (also known as Gusou): a mean, violent, stupid, and difficult man (also old and blind optically and morally); that Shun lived with him and his proudful and abusive stepmother; and, a half brother, Xiang (who was evil) -- but nevertheless, due to the young (early thirties, but old to be unmarried) Shun's great filial piety the inherent wickedness of the family was kept in-check and outright evil avoided. In an early example of the imperial examinations in Chinese mythology, Yao decided to test the merit of Shun. According to Zhou Dunyi and others, as a test for Shun, Yao married his two daughters Ehuang and Nuying to him and Shun took home his brides. The arrival of the future Xiang River goddesses, Ehuang and Nuying provoked numerous problems: Shun's father had little or no liking for him, his step mother had no love for him, both wanted to seize his dowry of flocks of sheep and other cattle and huge measures of grains which he had received as a part of the marriage, and his half brother Xiang just wanted to kill him and take his wives and some of his other possessions for himself. Shun's father, stepmother, and half brother decided to murder Shun. One day Shun's father, Gu, asked him to repair the roof of a barn, which Shun mentioned to his wives. Ehuang and Nuying warned him of the murder attempt and gave him a magical bird coat. Once Shun was up on the barn roof, his father, old Gu, set the barn on fire and took away the ladder; however, with the aid of the magical bird coat Shun flew to safety. Next, they tried to murder him in a well, but again Ehuang and Nuying had prepared him for survival with a magical dragon coat which allowed him to swim out through a tunnel. Again, Ehuang and Nuying saved Shun from his murderous relatives by giving him a magically antidotal bath which foiled a plot to get him drunk and murder him. There are many versions of this story and some of them omit the wives Ehuang and Nuying. In any case, Yao was well pleased with Shun's observed behavior, who maintained his filial piety while preserving his own interests as well, and so he promoted Shun into his civil service (which also allowed, or obligated, Shun together with Ehuang and Nuying to leave his home and murderous family behind). Later on, after Shun was promoted to emperor, Ehuang and Nuying were said to continue to provide Shun with invaluable advice contributing to his great success. (Murck 2000, 8-9; Wu 1982, 70-71; Yang and others 2005, 202-204).

Legend of the spotted bamboo

editThe spots that appear on the stems of certain bamboos legendarily first appeared on the bamboo growing by the Xiang River, caused by the tears which fell upon them, shed by Ehuang and Nuying, the two Xiang River goddesses, mourning the disappearance and presumed death of their beloved husband, the Emperor and hero Shun. There are various versions of this mythological story, but, according to one version, in the last year of his reign Shun decided to tour the country of the Xiang River area. According to another version he was engaged in a military expedition versus the "Miao". Upon his sudden death during this journey, in the "Wilderness of Cangwu", near the headwaters of the Xiang River in the Jiuyi Mountains (sometimes translated as Doubting Mountain),[2] both of his wives rushed from home to his body (or, in another version, to look for it, but were unable to find it), and then they wept by the river for days: their copious tears falling upon the bamboos by the river, stained them permanently with their spots.

The First Qin Emperor and Xiang Jun

editAccording to Sima Qian's History (Ch.6, "Annals of the First Qin Emperor"), in the 28th year of his reign (219 BCE), the Qin Emperor went on an excursion, wishing to visit the holy mountain of Heng (the southernmost of the Five Sacred Mountains of China, in present-day in Hunan). However, while attempting to travel there by boat, the emperor suddenly encountered a great wind which nearly prevented his safely reaching land (much less reaching his destination). The incident took place near the shrine of Xiang Jun (on Xiangshan, now an island in Dongting Lake). Upon inquiring about identity of Xiang Jun, the emperor learned that the name referred to the daughters of Yao and the wives of Shun who were buried at this location. Before returning home (by the different Wu Pass land route), the enraged emperor ordered 3000 convict laborers to cut down all of the trees on this mountain, and then to paint the entire mountain red.[3] Part of the reason for the Qin emperor's fury was that the Xiang goddess(es) were patron deities of his old enemies of the Kingdom of Chu; the color red was intended to symbolize the color of the clothing mandated for convicted criminals.[4]

Culture

editThe Xiang River goddesses (or deities) have been referenced in Classical Chinese poetry as far back as the early southern anthology the Chu ci, attributed to Qu Yuan.[5]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Murck (2000), p. 9.

- ^ Hawkes 2011, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Hawkes 2011, p. 104; Murck 2000, p. 10.

- ^ Hawkes (2011), p. 105.

- ^ 湘君 ("Xiang Jun") and 湘夫人 ("Xiang Furen") (text in Chinese, on Wikisource: both from the "Nine Songs") section of the Chuci.

References

edit- Hawkes, David, ed. (2011) [1985]. The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044375-2.

- Murck, Alfreda (2000). Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-00782-6.

- Strassberg, Richard E. (2018) [2002]. A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways through Mountains and Seas. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-29851-4.

- Wu, K. C. (1982). The Chinese Heritage. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-54475X.

- Yang, Lihui; An, Deming; Anderson Turner, Jessica (2008). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533263-6.