Xenorhinotherium is an extinct genus of macraucheniine macraucheniids, native to northern South America during the Pleistocene epoch, closely related to Macrauchenia of Patagonia. The type species is X. bahiense.[1]

| Xenorhinotherium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of X. bahiense | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Litopterna |

| Family: | †Macraucheniidae |

| Subfamily: | †Macraucheniinae |

| Genus: | †Xenorhinotherium Cartelle & Lessa, 1988 |

| Species: | †X. bahiense

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Xenorhinotherium bahiense | |

| |

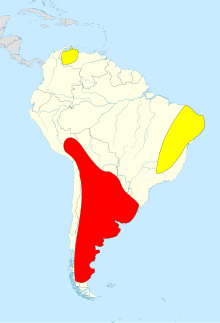

| Map showing the distribution of Macrauchenia in red, and Xenorhinotherium in yellow, inferred from fossil finds | |

Taxonomy

editSome authors consider the genus Xenorhinotherium a synonym of Macrauchenia, while all others consider it a distinct genus.[2] The name Xenorhinotherium means "Strange-Nosed Beast" and bahiense refers to the Brazilian state of Bahia, where the first fossils were found.[3]

Xenorhinotherium was a rather derived representative of the Macraucheniidae, a group of litopterns with camel-like appearances. Probably derived from lower Miocene forms such as Cramauchenia and Theosodon, this animal probably closely related to the large macraucheniids of the Pliocene and Pleistocene, such as Macrauchenia and Windhausenia.[4][5]

Below is a phylogenetic tree of the Macraucheniidae, based on the work of McGrath et al. 2018, showing the position of Xenorhinotherium.[4]

Characteristics

editX. bahiense was a megafaunal herbivore that probably looked very much like Macrauchenia, weighing about 940 kg (2,070 lb).[6] In life, X. bahiense would have vaguely resembled a tall, humpless camel with three toes on each foot and either a saiga-like proboscis[7] or a moose-like nose.[8] Pictographs from the Serranía de La Lindosa rock formation of Guaviare, Colombia, show what might possibly be Xenorhinotherium with three toes and a trunk, though the claims are highly controversial, and it is uncertain whether they even date to the last Ice Age.[9][10]

Paired δ13C and δ18O measurements from fossils in the Brazilian Intertropical Region indicate that X. bahiense was primarily a browser.[11]

Distribution

editFossils of Xenorhinotherium, dating from the Late Pleistocene to the Early Holocene, have been found in the states of Bahia, the Jandaíra Formation of Rio Grande do Norte,[1] and Minas Gerais in modern Brazil,[12] and also in Venezuela, in the localities of Muaco, Taima-Taima and Cuenca del Lago.[13][14]

Though not known from other countries, computer modelling suggests that the habitat in the western Andean slopes of Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru would have been suitable for this animal, particularly in areas that have not been extensively excavated yet.[2]

References

edit- ^ a b Xenorhinotherium at Fossilworks.org

- ^ a b de Oliveira, Karoliny; Araújo, Thaísa; Rotti, Alline; Mothé, Dimila; Rivals, Florent; Avilla, Leonardo S. (2020-03-01). "Fantastic beasts and what they ate: Revealing feeding habits and ecological niche of late Quaternary Macraucheniidae from South America". Quaternary Science Reviews. 231: 106178. Bibcode:2020QSRv..23106178D. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106178. ISSN 0277-3791. S2CID 213795563.

- ^ Cartelle, C.; Lessa, G. (1988). "Descrição de um novo gênero e espécie de Macrauchenidae (Mammalia, Litopterna) do Pleistoceno do Brasil" [Description of a new genus and species of Macrauchenidae (Mammalia, Litopterna) from the Pleistocene of Brazil]. Paulacoutiana (in Portuguese). 3: 3–26.

- ^ a b Andrew J. McGrath; Federico Anaya; Darin A. Croft (2018). "Two new macraucheniids (Mammalia: Litopterna) from the late middle Miocene (Laventan South American Land Mammal Age) of Quebrada Honda, Bolivia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (3): e1461632. Bibcode:2018JVPal..38E1632M. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1461632. S2CID 89881990.

- ^ Schmidt, Gabriela I.; Ferrero, Brenda S. (September 2014). "Taxonomic Reinterpretation of Theosodon hystatus Cabrera and Kraglievich, 1931 (Litopterna, Macraucheniidae) and Phylogenetic Relationships of the Family". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (5): 1231–1238. Bibcode:2014JVPal..34.1231S. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.837393. hdl:11336/18953. S2CID 86091386.

- ^ "Xenorhinotherium bahiense". The Extinctions. Retrieved 2022-12-09.

- ^ Palmer, Douglas, ed. (1999). The illustrated encyclopedia of dinosaurs and prehistoric animals. London: Marshall Pub. ISBN 1-84028-152-9. OCLC 44131898.

- ^ Moyano, Silvana Rocio; Giannini, Norberto Pedro (November 2018). "Cranial characters associated with the proboscis postnatal-development in Tapirus (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae) and comparisons with other extant and fossil hoofed mammals". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 277: 143–147. Bibcode:2018ZooAn.277..143M. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2018.08.005. hdl:11336/86349.

- ^ Morcote-Ríos, Gaspar; Aceituno, Francisco Javier; Iriarte, José; Robinson, Mark; Chaparro-Cárdenas, Jeison L. (29 April 2020). "Colonisation and early peopling of the Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene and the Early Holocene: New evidence from La Serranía La Lindosa". Quaternary International. 578: 5–19. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.04.026. S2CID 219014558.

- ^ "12,000-Year-Old Rock Drawings of Ice Age Megafauna Discovered in Colombian Amazon | Archaeology | Sci-News.com". Breaking Science News | Sci-News.com. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ^ Omena, Érica Cavalcante; Silva, Jorge Luiz Lopes da; Sial, Alcides Nóbrega; Cherkinsky, Alexander; Dantas, Mário André Trindade (3 October 2021). "Late Pleistocene meso-megaherbivores from Brazilian Intertropical Region: isotopic diet ( δ 13 C), niche differentiation, guilds and paleoenvironmental reconstruction ( δ 13 C, δ 18 O)". Historical Biology. 33 (10): 2299–2304. Bibcode:2021HBio...33.2299O. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1789977. ISSN 0891-2963. Retrieved 19 April 2024 – via Taylor and Francis Online.

- ^ Scherer, Carolina; Pitana, Vanessa; Ribeiro, Ana Maria (28 December 2009). "Proterotheriidae and Macraucheniidae (Litopterna, Mammalia) from the Pleistocene of Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil". Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 12 (3): 231–246. doi:10.4072/RBP.2009.3.06.

- ^ Socorro 2006, p. [page needed].

- ^ Morón 2015, p. 110.

Bibliography

edit- Morón, Camilo (January 2015). "Panorama geológico, paleontológico, arqueológico, histórico y mitológico del estado Falcón" [Geological panorama, paleontology, archeology, history and mythology in the State of Falcon, Venezuela]. Boletín Antropológico (in Spanish). 89 (1).

- Socorro, Orangel Antonio Aguilera (2006). Tesoros paleontológicos de Venezuela: el cuaternario del Estado Falcón [Paleontological treasures of Venezuela: the quaternary of the Falcón State] (in Spanish). Ministerio de la Cultura. ISBN 978-980-12-1379-6.

Further reading

edit- Nascimento, Karoliny de Oliveira (27 February 2019). Paleoecologia alimentar de macrauchenia patachonica e xenorhinotherium bahiense (macraucheniidae: litopterna: mammalia) e o reconhecimento de seus nichos ecológicos [Food paleoecology of macrauchenia patachonica and xenorhinotherium bahiense (macraucheniidae: litopterna: mammalia) and the recognition of their ecological niches] (Thesis) (in Portuguese).

- McGrath, Andrew J.; Anaya, Federico; Croft, Darin A. (4 May 2018). "Two new macraucheniids (Mammalia: Litopterna) from the late middle Miocene (Laventan South American Land Mammal Age) of Quebrada Honda, Bolivia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (3): e1461632. Bibcode:2018JVPal..38E1632M. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1461632. S2CID 89881990.

- de Oliveira, Karoliny; Araújo, Thaísa; Rotti, Alline; Mothé, Dimila; Rivals, Florent; Avilla, Leonardo S. (March 2020). "Fantastic beasts and what they ate: Revealing feeding habits and ecological niche of late Quaternary Macraucheniidae from South America". Quaternary Science Reviews. 231: 106178. Bibcode:2020QSRv..23106178D. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106178. S2CID 213795563.