Wet Hot American Summer is a 2001 American satirical comedy film directed by David Wain from a screenplay written by Wain and Michael Showalter. The film features an ensemble cast, with Janeane Garofalo and David Hyde Pierce starring alongside Molly Shannon, Paul Rudd, Christopher Meloni, Showalter (and various other members of the sketch comedy group The State), Marguerite Moreau, Ken Marino, Michael Ian Black, Zak Orth, A. D. Miles, Amy Poehler, Bradley Cooper (in his film debut), Marisa Ryan, Kevin Sussman, Joe Lo Truglio, and Elizabeth Banks. It takes place during the last full day at a fictional summer camp in 1981, and spoofs the sex comedies aimed at teen audiences of that era.

| Wet Hot American Summer | |

|---|---|

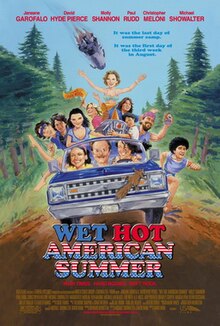

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Wain |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Howard Bernstein |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ben Weinstein |

| Edited by | Meg Reticker |

| Music by | Theodore Shapiro Craig Wedren |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | USA Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.8 million[3][4] |

| Box office | $295,206[5] |

The film was a critical and commercial failure, but has since developed a cult following,[6] and many of its cast members have gone on to high-profile work. Netflix revived the franchise with the release of an eight-episode prequel series starring most of the film's original cast, on July 31, 2015; and an eight-episode sequel series, set ten years after the original film, on August 4, 2017.

Plot

editThe film shows the last full day of a 1981 summer camp named Camp Firewood, located near Waterville, Maine, concentrating on the experiences of the camp counselors, most of whom are students aged around 16. The interleaved story threads meet in the evening at the camp talent show:

Cook Gene, a Vietnam War veteran, clumsily tries to hide his various sexual fetishes. But after being encouraged by a talking can of vegetables, he proudly admits them all in front of the packed food hall, to great applause.

Zealous drama instructors Ben and Susie try to organize a talent show to be held on the last evening. Ben is in love with counselor McKinley. They have passionate sex and are later symbolically married by Beth in a ceremony by the lake. Beth forces Ben and Susie to give the last slot of their talent show to strange outsider Steve. He surprises everyone when during his time on stage an intense storm breaks out inside and outside the venue, seemingly created only with the power of Steve's mind. He receives a wild ovation.

Counselor Coop is secretly in love with counselor Katie, but she is dating attractive but obnoxious and inconsiderate lifeguard Andy, who cheats on her, e.g. with counselor Lindsay. Katie has decided to find a girl for Coop and when they spend time together during the day, Katie develops feelings for him. Eventually they kiss, but Katie soon returns to Andy and tells Coop that they made a mistake. A devastated Coop is found by Gene, who performs a rigorous training regimen with him. A newly buff Coop impresses Katie at the talent show and she declares her love for him. But when both bid farewell the next morning, she explains that she has returned to Andy again, even though she knows he is a terrible boyfriend, because he is very attractive and she is only interested in sex at the moment, leaving Coop speechless.

Camp director Beth is attracted to Henry, an associate professor of astrophysics who vacations near the camp. She asks him to come over and teach the campers about space. After rudely rejecting her first, he changes his mind and does science projects with a group of nerdy children, bonding with them and getting closer to Beth, eventually sleeping with her. Henry and the children discover that a piece of Skylab will deorbit this evening and will probably impact the camp. They build a contraption to pinpoint the precise location: the talent show venue. Henry thinks he can modify the machine so that it can influence the path of the space debris. After he and the children use the modified machine near the talent show during the storm, the debris lands harmlessly on the grass.

Counselor Victor tries to give the impression that he has sexual experience, but is secretly a virgin. He is promised sex by the promiscuous Abby this night, but is told by Beth to go on a rafting trip with several campers and Neil. He abandons them at the river, steals the van and tries to return to Abby. He crashes the van, but reaches the camp on foot in the evening, where Abby has forgotten about him. When Neil and the children get lost on the river, Neil abandons them on the raft to look for Victor. He finds him at the camp and brings him back to the river, just in time to save the children.

Arts and crafts instructor Gail has a nervous breakdown during class. The children perform a group therapy session with her, during which she admits that she is not yet over her ex-husband Ron. With the help of the children, especially Aaron, she finally finds the courage to reject Ron when he arrives during the talent show and asks her to come back to him. The next morning, Gail and Aaron declare their love for each other.

Cast

edit- Janeane Garofalo as Beth

- David Hyde Pierce as Professor Henry Newman

- Molly Shannon as Gail von Kleinenstein

- Paul Rudd as Andy

- Christopher Meloni as Gene

- Michael Showalter as Gerald "Coop" Cooperberg/Alan Shemper

- Marguerite Moreau as Katie Finnerty

- Ken Marino as Victor Pulak

- Michael Ian Black as McKinley

- Zak Orth as J.J.

- A. D. Miles as Gary

- Nina Hellman as Nancy

- Amy Poehler as Susie

- Bradley Cooper as Ben

- Marisa Ryan as Abby Bernstein

- Kevin Sussman as Steve

- Elizabeth Banks as Lindsay

- Joe Lo Truglio as Neil

- Judah Friedlander as Ron von Kleinenstein

- H. Jon Benjamin as Can of Mixed Vegetables

- Donna Mitchell as Gene's Wife

Production

editBackground

editThe film is based on the experiences Wain had while attending Jewish camps, particularly Camp Wise in Claridon Township, Ohio and Camp Modin in Belgrade, Maine.[7][8] Showalter also drew on his experiences he had at Camp Mohawk in the Berkshires in Cheshire, Massachusetts.[9] During one scene, the counselors take a trip into Waterville, Maine, which is not far from the camp. It is also a parody of, and homage to, other films about summer camp, including Meatballs (1979), Little Darlings (1980), Sleepaway Camp (1983),[10] and Indian Summer (1993). According to Wain, they wanted to make a film structured like the films Nashville, Dazed and Confused and Do the Right Thing—"films that take place in one contained time period that have lots of different characters."[4]

Development

editThe film's financing took three years to assemble; in a June 2011 interview, Wain revealed the film's budget was $1.8 million; he noted that during the 2001 Sundance Film Festival,[11] the film had been promoted as costing $5 million, in an attempt to attract a better offer from a distributor.[4] Because of the film's relatively small budget, the cast was paid very little; Paul Rudd has stated that he is uncertain that he received any compensation at all for the film.[12]

Filming

editPrincipal photography lasted 28 days in May 2000, and, according to director David Wain, it rained on every day of shooting.[4] Exterior shots were filmed when possible, sometimes under covers or umbrellas, but some scenes were moved indoors instead. In many interior scenes, rain seen outside turns into sun as soon as characters step outside. Due to the cold, the actors' breath can be seen in some outdoor scenes.[4] The film was shot at Camp Towanda in Honesdale, Pennsylvania.[13]

Music

editAs the film is set in the early 1980s, the film's soundtrack features songs from many popular bands of the era, most notably Jefferson Starship, Rick Springfield, Loverboy, and KISS.

- Songs in the film

- "Jane" by Jefferson Starship

- "Juke Box Hero" by Foreigner

- "Backwards from Three" by Craig Wedren and Theodore Shapiro

- "Wet Hot American Summer" by Craig Wedren

- "Love Is Alright Tonite" by Rick Springfield

- "Danny's Song" by Loggins & Messina

- "Turn Me Loose" by Loverboy

- "Beth" by Kiss

- "Day by Day" from Godspell

- "Harden My Heart" by Quarterflash

- "Higher and Higher" by Craig Wedren and Theodore Shapiro

- "When It's Over" by Loverboy

- "Wet Hot American Dream" by Peter Salett

- "Summer in America" by Mr. Blue & Chubb Rock

Release

editTheatrical

editWet Hot American Summer premiered at the 2001 Sundance Film Festival, where it was screened four times to sold-out crowds,[14] though it failed to attract a distributor.[4] Months later, USA Films offered the filmmakers $100,000 for the film, with virtually no participation for the filmmakers, an offer the film's investors accepted. It premiered in New York City on July 27, 2001, then received a limited theatrical release in fewer than 30 cities.[14]

Home media

editThe film was released in both VHS and DVD formats on January 15, 2002 by USA Home Entertainment.[14] In 2011, Wain tried to convince Universal Studios to prepare either a 10th anniversary home video re-release with extra features, or a Blu-ray release, but Universal rejected the ideas. The film was released on Blu-ray on May 12, 2015.[15]

Reception

editWet Hot American Summer received mostly negative reviews from critics. Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a rating of 38%, based on 76 reviews, with an average rating of 4.85/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Wet Hot American Summer's incredibly talented cast is too often outmatched by a deeply silly script that misses its targets at least as often as it skewers them."[16] Metacritic gives the film a score of 42 out of 100, based on 24 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[17]

Roger Ebert rated the film with one star out of four. His review took the form of a tongue-in-cheek parody of Allan Sherman's "Hello Muddah, Hello Fadduh".[18]

In contrast, Entertainment Weekly's Owen Gleiberman awarded the film an "A", and named it as one of the ten best films of the year.[19] Newsweek's David Ansen also lauded it, calling it a "gloriously silly romp" that "made me laugh harder than any other movie this summer. Make that this year."[20] The film has gone on to achieve a cult following.[12]

Actress Kristen Bell stated on NPR on September 2, 2012, that Wet Hot American Summer was her favorite film, having watched it "hundreds of times."[21] NPR host Jesse Thorn said on the April 29, 2014 episode of Bullseye:

When someone has an open enough heart to accept this silliness—and that's what it's about for me, an open heart—if someone's heart is open to Wet Hot American Summer, they love it. And that's when I know that me and them, we've got an unbreakable bond. Together forever. Like camp counselors.[22]

Follow-ups

editThe film is followed by two Netflix series, with one serving as a prequel and one as a sequel. The prequel, First Day of Camp, was released on July 31, 2015,[23] while the sequel, Ten Years Later, was released on August 4, 2017.[24]

Legacy

editThe professional wrestler Orange Cassidy, who has the gimmick of a slacker character, is largely based on Paul Rudd's portrayal of Andy in the film, even going as far as to have "Jane" by Jefferson Starship (which is used in the film's opening credits) as his entrance music.[25]

Anniversary celebrations

editEvents were held around the country to celebrate the film's 10-year anniversary in 2011 and 2012, including a screening of the film in Boston,[26] an art show in Santa Monica of works inspired by the film, with a reception hosted by Wain,[27] a screening at the Los Angeles Film School with a Q&A with Wain,[28] a 10th anniversary celebration event with the members of Stella in Brooklyn,[3] and a reading of the script at the San Francisco Comedy Festival, with much of the original cast.[29]

Undeveloped TV series

editDuring a 2015 interview with Variety, Wain and Showalter stated that they wrote a pilot for a possible Fox television series based on the film. Wain described the series as a "22-minute Fox sitcom with commercials and nothing Rated R, so it was a little bit odd."[30] The pilot was not picked up for a series.

Documentary

editAlongside the prequel series, a making-of documentary, Hurricane of Fun: The Making of Wet Hot, was released on Netflix on July 24, 2015, consisting of behind-the-scenes interviews and footage shot during the filming of the movie.

References

edit- ^ Harvey, Dennis (January 30, 2001). "Wet Hot American Summer". Variety. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ "Wet Hot American Summer". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Collis, Clark (August 2, 2011). "Wet Hot American Summer 10th anniversary: David Wain, Michael Showalter, and Joe Lo Truglio remember their days at Camp Firewood". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 28, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Jeff Goldsmith (June 17, 2011). "David Wain – Wet Hot American Summer". Q&A with Jeff Goldsmith (Podcast). Blogger/Liberated Syndication. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ "Wet Hot American Summer (2001)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on June 17, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ Tobias, Scott (June 11, 2008). "The New Cult Canon: Wet Hot American Summer". The AV Club. Archived from the original on March 1, 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ Krutchik, Alex (December 3, 2021). "Director Wain shares Camp Wise inspiration behind 'Wet Hot American Summer'". Cleveland Jewish News. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ Benson, John (October 23, 2020). "'Wet Hot American Summer' director, an Ohio native, reunites with all-star cast for live read". The Chronicle-Telegram. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ "The Rumpus interview with Michael Showalter". The Rumpus. February 24, 2009. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ Scheer, Paul (October 30, 2012). "Sleepaway Camp, episode #48 of How Did This Get Made?". Earwolf. Archived from the original on July 29, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Wet Hot American Summer". Archives. Sundance Institute. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Collis, Clark (July 30, 2015). "'Wet Hot American Summer': The crazy story behind the cult classic". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- ^ "Full Credit List". Wet Hot American Summer official website. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Wet Hot history". Wet Hot American Summer official website. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ "From Universal Pictures Home Entertainment: Wet Hot American Summer – UNIVERSAL CITY, Calif" (Press release). PR Newswire. April 13, 2015. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ "Wet Hot American Summer (2001)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ "Wet Hot American Summer (2001)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ^ "Wet Hot American Summer". Chicago Sun-Times. Roger Ebert Reviews. August 31, 2001. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (July 25, 2001). "Wet Hot American Summer". EW.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2022. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ Ansen, David (August 26, 2001). "Summer Camp". Newsweek. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ "The Movie Kristen Bell Has 'Seen A Million Times'". NPR.org. September 1, 2012. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ "Bullseye with Jesse Thorn: Jim Rash, Bob Saget, Jessica St. Clair and Lennon Parham". Maximum Fun. April 29, 2014. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ "Wet Hot American Summer: First Day of Camp: Season 1". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ "Netflix is going back to camp with Wet Hot American Summer: Ten Years Later". The A.V. Club. April 27, 2016. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Jeremy (June 29, 2022). "Orange Cassidy Gets New Entrance Theme On AEW Dynamite". 411Mania.com. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Coolidge Corner Theatre – Wet Hot American Summer". Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ "Wet Hot American Summer is 10, parties include a Stella-hosted show in Brooklyn". BrooklynVegan.com. June 10, 2011. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ "The Los Angeles Film School and Jeff Goldsmith Present: "Wet Hot American Summer: 10 Years Later" followed by Q&A with Director David Wain". Los Angeles Film School. September 26, 2017. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ "The Cast Of Wet Hot American Summer Reunited At SF Sketchfest". thelaughbutton.com. January 29, 2012. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ Seabaugh, Julie (July 29, 2015). "'Wet Hot American Summer': Oral History Details False Starts, Faking Camp Firewood". Variety. Archived from the original on May 19, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2017.