| Battleship Potemkin | |

|---|---|

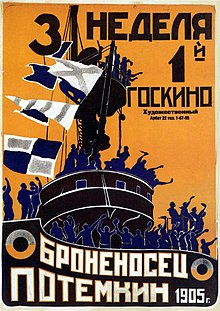

Original Soviet release poster | |

| Directed by | Sergei Eisenstein |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Jacob Bliokh |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Goskino |

Release date |

|

Running time | 75 minutes |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Languages |

|

Battleship Potemkin ([Броненосец «Потёмкин»] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help), [Bronenosets Patyomkin] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), sometimes rendered as Battleship Potyomkin, is a 1925 Soviet silent film directed by Sergei Eisenstein and produced by Mosfilm. It presents a dramatized version of the mutiny that occurred in 1905 when the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin rebelled against their officers.

Battleship Potemkin was named the greatest film of all time at the Brussels World's Fair in 1958.[1][2][3]

Plot edit

The film is set in June 1905; the protagonists of the film are the members of the crew of the Potemkin, a battleship of the Imperial Russian Navy's Black Sea Fleet. Eisenstein divided the plot into five acts, each with its own title:

Act.. I: Men and Maggots edit

The scene begins with two sailors, Matyushenko and Vakulinchuk, discussing the need for the crew of the Potemkin to support the revolution taking place within Russia. While the Potemkin is anchored off the island of Tendra, off-duty sailors are sleeping in their bunks. As an officer inspects the quarters, he stumbles and takes out his aggression on a sleeping sailor. The ruckus causes Vakulinchuk to awake, and he gives a speech to the men as they come to. Vakulinchuk says, "Comrades! The time has come when we too must speak out. Why wait? All of Russia has risen! Are we to be the last?" The scene cuts to morning above deck, where sailors are remarking on the poor quality of the meat for the crew. The meat appears to be rotten and covered in worms, and the sailors say that "even a dog wouldn't eat this!" The ship's doctor, Smirnov, is called over to inspect the meat by the captain. Rather than worms, the doctor says that the insects are maggots, and they can be washed off prior to cooking. The sailors further complain about the poor quality of the rations, but the doctor declares the meat edible and ends the discussion. Senior officer Giliarovsky forces the sailors still looking over the rotten meat to leave the area, and the cook begins to prepare borscht although he too questions the quality of the meat. The crew refuses to eat the borscht, instead choosing bread and water, and canned goods. While cleaning dishes, one of the sailors sees an inscription on a plate, which reads "give us this day our daily bread." After considering the meaning of this phrase, the sailor smashes the plate and the scene ends.

Act.. II: Drama on the Deck edit

All those who refuse the meat are judged guilty of insubordination and are brought to the fore-deck where they receive religious last rites. The sailors are obliged to kneel and a canvas cover is thrown over them as a firing squad marches onto the deck. The First Officer gives the order to fire, but the sailors in the firing squad lower their rifles and the uprising begins. The sailors overwhelm the outnumbered officers and take control of the ship. The officers are thrown overboard, the ship's priest is dragged out of hiding, and finally the doctor is thrown into the ocean as 'food for the fish'.

Act.. III: A Dead Man Calls for Justice edit

The mutiny is successful but Vakulinchuk, the charismatic leader of the rebels, is killed. The Potemkin arrives at the port of Odessa. Vakulinchuk's body is taken ashore and displayed publicly by his companions in a tent with a sign on his chest that says "For a spoonful of soup" (Изъ-за ложки борща). The sailors gather to make a final farewell and praise Vakulinchuk as a hero. The people of Odessa welcome the sailors, but they attract the police.

Act.. IV: The Odessa Steps edit

The best known sequence of the film is set on the Odessa steps, connecting the waterfront with the central city. A detachment of dismounted Cossacks forms a line at the top of the steps and march towards a crowd of unarmed civilians including women and children. The soldiers halt to fire a volley into the crowd and then continue their impersonal, machine-like advance. Brief sequences show individuals amongst the people fleeing or falling, a baby's pram rolling down the steps, a woman shot in the face, broken spectacles and the high boots of the soldiers moving in unison.

In retaliation, the sailors of the Potemkin decide to fire on a military headquarters with the guns of the battleship. Meanwhile, there is news that a squadron of loyal warships is coming to quell the revolt of Potemkin.

Act.. V: One against all edit

The sailors of the Potemkin decide to go all the way and lead the battleship from the port of Odessa to face the fleet of the Tsar. Just when the battle seems inevitable, the sailors of the formerly loyal ships incredibly refuse to open fire on their comrades, externalizing with songs and shouts of joy their solidarity with the mutineers and allowing them to pass unmolested through the fleet, waving the red flag.

Soundtracks edit

To retain its relevance as a propaganda film for each new generation, Eisenstein hoped the score would be rewritten every 20 years. The original score was composed by Edmund Meisel. A salon orchestra performed the Berlin premiere in 1926. The instruments were flute/piccolo, trumpet, trombone, harmonium, percussion and strings without viola. Meisel wrote the score in twelve days because of the late approval of film censors. As time was so short Meisel repeated sections of the score. Composer/conductor Mark-Andreas Schlingensiepen has reorchestrated the original piano score to fit the version of the film available today.

Nikolai Kryukov composed a new score in 1950 for the 25th anniversary. In 1985, Chris Jarrett composed a solo piano accompaniment for the movie. In 1986 Eric Allaman wrote an electronic score for a showing that took place at the 1986 Berlin International Film Festival. The music was commissioned by the organizers, who wanted to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the film's German premiere. The score was played only at this premiere and has not been released on CD or DVD. Contemporary reviews were largely positive apart from negative comment because the music was electronic. Allaman also wrote an opera about Battleship Potemkin, which is musically separate from the film score.

In its commercial format, on DVD for example, the film is usually accompanied by classical music added for the 50th anniversary edition re-released in 1975. Three symphonies from Dmitri Shostakovich have been used, with No. 5 beginning and ending the film, being the most prominent. In 2007, Del Rey & The Sun Kings also recorded this soundtrack. In an attempt to make the film relevant to the 21st century, Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe (of the Pet Shop Boys) composed a soundtrack in 2004 with the Dresden Symphonic Orchestra. Their soundtrack, released in 2005 as Battleship Potemkin, premiered in September 2004 at an open-air concert in Trafalgar Square, London. There were four further live performances of the work with the Dresdner Sinfoniker in Germany in September 2005 and one at the Swan Hunter ship yard in Newcastle upon Tyne in 2006.

The avant-garde jazz ensemble Club Foot Orchestra has also re-scored the film, and performed live accompanying the film. For the 2005 restoration of the film, under the direction of Enno Patalas in collaboration with Anna Bohn, released on DVD and Blu-ray, the Deutsche Kinemathek - Museum fur Film und Fernsehen, commissioned a re-recording of the original Edmund Meisel score, performed by the Babelsberg Orchestra, conducted by Helmut Imig. In 2011 the most recent restoration was completed with an entirely new soundtrack by members of the Apskaft group. Contributing members were AER20-200, awaycaboose, Ditzky, Drn Drn, Foucault V, fydhws, Hox Vox, Lurholm, mexicanvader, Quendus, Res Band, -Soundso- and speculativism. The entire film was digitally restored to a sharper image by Gianluca Missero (who records under the name Hox Vox). The new version is available at the Internet Archive.[4]

Critical reaction edit

Battleship Potemkin has received universal acclaim from modern critics. On review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an overall 100% "Certified Fresh" approval rating based on 44 reviews, with a rating average of 9.1 out of 10. The site's consensus reads, "A technical masterpiece, Battleship Potemkin is Soviet cinema at its finest, and its montage editing techniques remain influential to this day."[5] Since its release, Battleship Potemkin has often been cited as one of the finest propaganda films ever made and considered amongst the greatest films of all time.[1][6] The film was named the greatest film of all time at the Brussels World's Fair in 1958.[2] Similarly, in 1952, Sight & Sound magazine cited The Battleship Potemkin as the fourth greatest film of all time and has been voted within the top ten in the magazine's five subsequent decennial polls, dropping to number 11 in the 2012 poll.[7]

In 2007, a two-disc, restored version of the film was released on DVD. Time magazine's Richard Corliss named it one of the Top 10 DVDs of the year, ranking it at #5.[8] It ranked #3 in Empire's "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[9] In April 2011, Battleship Potemkin was re-released in UK cinemas, distributed by the British Film Institute. On its re-release, Total Film magazine gave the film a five-star review, stating: "...nearly 90 years on, Eisenstein’s masterpiece is still guaranteed to get the pulse racing."[10]

Directors Orson Welles,[11] Michael Mann[12] and Paul Greengrass[13] placed Battleship Potemkin on their list of favorite films.

Director Billy Wilder has named Battleship Potemkin as his favourite film of all time.

- ^ a b What's the Big Deal?: Battleship Potemkin (1925). Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ a b "Battleship Potemkin by Roger Ebert". Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ "Top Films of All-Time". Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ "Apskaft Presents: The Battleship Potemkin". Internet Archive. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin (1925)". Rotten Tomatoes (Flixster). Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin". Archived from the original on 2011-03-26. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ "Sight and Sound Historic Polls". BFI. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ^ Corliss, Richard; Top 10 DVDs; time.com

- ^ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema – 3. The Battleship Potemkin". Empire.

- ^ "Battleship Potemkin". Total Film. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ "Fun Fridays – Director's Favourite Films – Orson Welles - Film Doctor". Film Doctor. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ "FUN FRIDAYS – DIRECTOR'S FAVOURITE FILMS – MICHAEL MANN - Film Doctor". Film Doctor. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ "Fun Fridays – Director's Favourite Films – Paul Greengrass - Film Doctor". Film Doctor. Retrieved 19 November 2015.