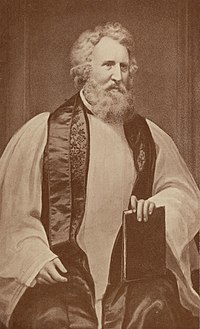

John Henry Hopkins (January 30, 1792 – January 9, 1868) was the first bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Vermont and was the eighth Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America.

Early life and career edit

John Henry Hopkins was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1792, the son of Thomas Hopkins and his wife, Elizabeth Fitzakerly,[1] and came to the United States in 1801, where he later became an iron manufacturer in Pennsylvania. The War of 1812 having proved disastrous to his business, he studied law, and began practice in Pittsburgh.

Ministry edit

In 1823, Hopkins entered the ministry of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, in response to the call of the church in which he was a vestryman. In 1831, he accepted the charge of Trinity Church, Boston, and the next year was elected the first bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Vermont, taking also the rectorship of a church in Burlington. He took great interest in education and made heavy economic sacrifices for its promotion. After 1856, he devoted his whole time to the care of the Diocese.

Presiding Bishop edit

John Henry Hopkins was the eighth presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church and served from January 13, 1865 to January 9, 1868. Largely through the efforts of Presiding Bishop Hopkins and his friend Bishop Stephen Elliott of Georgia, who was the presiding bishop of the breakaway Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, the Northern and Southern branches of the Church were reunited after the end of the Civil War. Both men considered this crucial to the survival of the Church and the nation.

Later life edit

Bishop Hopkins served for a time as the Chancellor of the University of Vermont and was later prominent in the Lambeth Conference in London in 1867. He died the next January at Rock Point and was buried there at Bishop’s House, Rock Point, Burlington, Vermont.

Family edit

On May 8, 1816, John Henry Hopkins married Melusina Muller and they had 13 children.[1] In the year 1866 most of their large family gathered at the family home at Rock Point to celebrate their Golden Wedding anniversary. A book was published by their daughter-in-law, Alice Leavenworth Hopkins (married to Theodore, see below), to commemorate the event. One on their sons was John Henry Hopkins, Jr., born on October 28, 1820, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who became an Episcopal priest and hymn writer, and delivered the eulogy at the Funeral of President Ulyesses S Grant in 1885. He died on August 14, 1891, in Hudson, New York and is buried with his father at Bishop’s House, Rock Point.[2] Many of the Bishop's children were multi-talented and multi-disciplined. One of the elder sons, Theodore Austin Hopkins, took over at Rock Point as Headmaster for many years before entering local politics as a town auditor in South Burlington. He was also a gifted musician and architect, having designed a lovely Queen Anne Victorian home for his family to reside in that stands to this day in Vermont. Another son, Charles Jerome Hopkins, known commonly as "Jerome" or "C.J." Hopkins in musical circles, was a composer and fierce advocate of public support for American musical composition and for free education in the musical arts. One of Jerome's best known pieces was "The Wind Demon," though he composed over 700 pieces over the course of his lifetime, including the sacred opera "Samuel." One of Bishop Hopkins' great-grandchildren was the illustrious Dorothy Canfield Fisher, renowned for being the namesake of the prestigious literary award in children's publishing. Teachers, pioneers, scientists, medical doctors, artists, musicians, men and women of holy orders... Bishop Hopkins' children continued a long and proud legacy of academia and creativity. Annually, until the mid-1980s, the "Hopkinsfolk" would travel to Vermont to have a reunion. When time, energy, and the sheer numbers of people prohibited this reunion, the gatherings ceased. Many of the Hopkins descendants live far and wide across the United States today.

One Hopkins descendant appeared on the popular television show Antiques Roadshow with a family portrait painted by Bishop Hopkins, accompanied by photographs of Rev. Hopkins and his wife, and a letter describing the portrait and the family. Members of the Vermont Historical Society in the 1800s, the Bishop, his wife and children knew the value of preserving family memorabilia. Many of their family letters are annotated with dates and relative data so as to tell future generations the story of their lives. Hopkins family records are available at the University of Vermont and Harvard University.

Works edit

Hopkins was a prolific writer, leaving nearly 20 published works, among which are:

- Christianity Vindicated (1833)

- The Primitive Creed Examined and Explained (1834)

- The Novelties which Disturb our Peace (1844)

- History of the Confessional (1850)

- The American Citizen: His Rights and Duties (1857)

- A Scriptural, Ecclesiastical, and Historical View of Slavery (1864)

Hopkins was also a fine painter and left several family portraits and a book of prints filled with his botanical observations of flowers and other plant-life. His architectural legacy has been mostly erased, unfortunately, as his beautiful gothic St. Paul's Cathedral in Burlington, Vermont was destroyed by fire in 1972. Many plates of his designs for the cathedral and other studies made of Gothic architecture survive, however, and are in the University of Vermont Historical Archives.

Slavery and the Church edit

"A Scriptural, Ecclesiastical, and Historical View of Slavery" (1864) edit

John Henry Hopkins wrote in his book A Scriptural Ecclesiastical and Historical View of Slavery that his research "only strengthened my convictions as to the sanction which the Scriptures give to the principle of negro slavery"[3]. Bishop Hopkins wrote this book in order to collect together all the Scriptural arguments for and against negro slavery, but with the specific purpose of ultimately proving the Christian sanction of slavery. The book arose mainly out of a growing interest in Bishop Hopkins’ precursory pamphlet entitled “Papers from the Society for the Diffusion of Political Knowledge,” in which Bishop Hopkins, by the request of several gentlemen from New York, presented his opinion on the subject of negro slavery in the South. The pamphlet drew attention, particularly from another group of gentlemen from Philadelphia who, on April 15, 1863, requested Bishop Hopkins to again address the question of slavery in writing. Bishop Hopkins then decided to write his book as an official interpretation of the Scriptures regarding slavery, in which he included the original pamphlet and letter of request.

Personal View edit

It is interesting to note that while Bishop Hopkins argued that the Scriptures sanctioned slavery, he personally did not approve of slavery and even stated his agreement with abolition.

And therefore, while I should rejoice in the adoption of any plan of gradual abolition which could be accepted peacefully by general consent, I can not see that we have any right to interfere with the domestic institutions of the South, either by the law or by the Gospel.[4]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b Who Was Who in America, vol. 1, 1897-1942, (1943) Chicago: Marquis Who's Who, p. 259

- ^ http://www.cyberhymnal.org/bio/h/o/p/hopkins_jh.htm

- ^ Hopkins, John Henry. A Scriptural, Ecclesiastical, and Historical View of Slavery from the Days of the Patriarch Abraham, to the Nineteenth Century. New York: W. I. Pooley & Co., 1864, http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&id=S1ZEtrmbPRwC&dq=a+scriptural+ecclesiastical+and+historical+view+of+slavery&printsec=frontcover&source=web&ots=lq1zZfAUEb&sig=OQeyVzKp_a4RoPzwhbhFbalFFZE&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=4&ct=result#PPA5,M1]

- ^ Hopkins, p.5

- John Henry Hopkins, Jr. (his son), Biography (New York, 1873)

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)