==Life cycle==

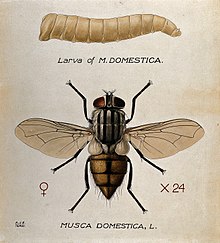

Each female housefly can lay up to 500 eggs in her lifetime, in several batches of about 75 to 150. The eggs are white and are about 1.2 mm (1⁄16 in) in length, and they are deposited by the fly in a suitable place, usually dead and decaying organic matter, such as food waste, carrion, or feces. Within a day, larvae (maggots) hatch from the eggs; they live and feed where they were laid. They are pale-whitish, 3 to 9 mm (1⁄8 to 11⁄32 in) long, thinner at the mouth end, and legless.[1] Larval development takes from two weeks, under optimal conditions, to 30 days or more in cooler conditions. The larvae avoid light; the interiors of heaps of animal manure provide nutrient-rich sites and ideal growing conditions, warm, moist, and dark.[1]

At the end of their third instar, the larvae crawl to a dry, cool place and transform into pupae. The pupal case is cylindrical with rounded ends, about 1.2 mm (1⁄16 in) long, and formed from the last shed larval skin. It is yellowish at first, darkening through red and brown to nearly black as it ages. Pupae complete their development in two to six days at 35 °C (95 °F), but may take 20 days or more at 14 °C (57 °F).[1]

When metamorphosis is complete, the adult housefly emerges from the pupa. To do this, it uses the ptilinum, an eversible pouch on its head, to tear open the end of the pupal case. The adult housefly lives from two weeks to one month in the wild, or longer in benign laboratory conditions. Having emerged from the pupa, it ceases to grow; a small fly is not necessarily a young fly, but is instead the result of getting insufficient food during the larval stage.[1]

Male houseflies are sexually mature after 16 hours and females after 24. Females produce a pheromone, (Z)-9-tricosene (muscalure). This cuticular hydrocarbon is not released into the air and males sense it only on contact with females;[2] it has found use as in pest control, for luring males to fly traps.[3][4] The male initiates the mating by bumping into the female, in the air or on the ground, known as a "strike". He climbs on to her thorax, and if she is receptive, a courtship period follows, in which the female vibrates her wings and the male strokes her head. The male then reverses onto her abdomen and the female pushes her ovipositor into his genital opening; copulation, with sperm transfer, lasts for several minutes. Females normally mate only once and then reject further advances from males, while males mate multiple times.[5] A volatile semiochemical that is deposited by females on their eggs attracts other gravid females and leads to clustered egg deposition.[6]

The larvae depend on warmth and sufficient moisture to develop; generally, the warmer the temperature, the faster they grow. In general, fresh swine and chicken manures present the best conditions for the developing larvae, reducing the larval period and increasing the size of the pupae. Cattle, goat, and horse manures produce fewer, smaller pupae, while fully composted swine manure, with a water content under 40%, produces none at all.[7] Pupae can range from about 8 to 20 milligrams in weight under different conditions.[8]

The life cycle can be completed in seven to 10 days under optimal conditions, but may take up to two months in adverse circumstances. In temperate regions, 12 generations may occur per year, and in the tropics and subtropics, more than 20.[1]

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

IFASwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Dahlem GA (2009). "House Fly (Musca domestica)". In Resh VH, Carde RT (eds.). Encyclopedia of Insects (2 ed.). Elsevier. pp. 469–470.

- ^ Thom C, Gilley DC, Hooper J, Esch HE (September 2007). "The scent of the waggle dance". PLoS Biology. 5 (9): e228. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050228. PMC 1994260. PMID 17713987.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "(Z)-9-Tricosene (103201) Fact Sheet" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Murvosh CM, Fye RL, LaBrecque GC (1964). "Studies on the mating behavior of the house fly, Musca domestica L.". Ohio Journal of Science. 64 (4): 264–271. hdl:1811/5017.

- ^ Jiang Y, Lei C, Niu C, Fang Y, Xiao C, Zhang Z (October 2002). "Semiochemicals from ovaries of gravid females attract ovipositing female houseflies, Musca domestica" (PDF). Journal of Insect Physiology. 48 (10): 945–950. doi:10.1016/s0022-1910(02)00162-2. PMID 12770041.

- ^ Breitwart; et al. (2008). "Favorability of conditions in the reproduction and development of the common housefly: a controlled study". International Journal of Entomology. 21 (11): 157–181.

- ^ Larraín P, Salas C, Salas F (2008). "House fly (Musca domestica L.) (Diptera: Muscidae) development in different types of manure [Desarrollo de la Mosca Doméstica (Musca domestica L.) (Díptera: Muscidae) en Distintos Tipos de Estiércol]". Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research. 68 (2): 192–197. doi:10.4067/S0718-58392008000200009. ISSN 0718-5839.