| Neanderthal Temporal range: Middle to Late Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

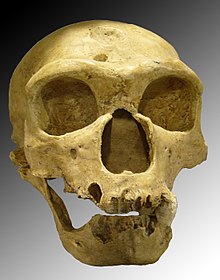

| Neanderthal skull at La Chapelle-aux-Saints. | |

| |

| Mounted Neanderthal skeleton at American Museum of Natural History. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. sapiens

|

| Subspecies: | H. s. neanderthalensis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Homo sapiens neanderthalensis | |

| |

| Range of Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. Eastern and northern ranges may extend to include Okladnikov in Altai and Mamotnaia in Ural | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Homo mousteriensis[2] | |

The Neanderthals or Neandertals UK: /niˈændərˌtɑːlz/, us also /neɪ/-, -/ˈɑːndər/-, -/ˌtɔːlz/, -/ˌθɔːlz/)[4][5] (from Neandertaler) are an extinct subspecies of human in the genus Homo. They are closely related to modern humans,[6][7] differing in DNA by just 0.12%.[8] Remains left by Neanderthals include bone and stone tools, which are found in Eurasia, from Western Europe to Central and Northern Asia as well as in North Africa. Neanderthals are generally classified by biologists as a subspecies of Homo sapiens (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis), but a minority considers them to be a species (Homo neanderthalensis).[9][10]

Several cultural assemblages have been linked to the Neanderthals in Europe. The earliest, the Mousterian stone tool culture, dates to about 300,000 years ago.[11] Late Mousterian artifacts were found in Gorham's Cave on the south-facing coast of Gibraltar.[12][13]

With an average cranial capacity of 1600 cm3,[14] the cranial capacity of Neanderthals is notably larger than the 1400 cm3 average for modern humans, indicating that their brain size was larger. This difference in brain size can be attributed to the cold climate adaptations discussed in Allen's Rule. Also, owing to larger body size, Neanderthals are less encephalized.[15] Males stood 164–168 cm (65–66 in) and females 152–156 cm (60–61 in) tall.[16]

Genetic evidence published in 2010 and 2014 suggests that Neanderthals contributed to the DNA of anatomically modern humans, including most non-Africans as well as a few African populations, through interbreeding, likely between 50,000 to 60,000 years ago.[17][18][19]

In December 2013, researchers reported evidence that Neanderthals practiced burial behavior and intentionally buried their dead.[20] In addition, scientists reported having sequenced the entire genome of a Neanderthal for the first time. The genome was extracted from the toe bone of a 50,000-year-old Neanderthal found in a Siberian cave.[21][22][23]

Name edit

The species is named after the site of its first discovery, which is about 12 km (7.5 mi) east of Düsseldorf, Germany, in the Feldhofer Cave in the river Düssel's Neander valley.[24] Thal is the older spelling of the German word Tal (with the same pronunciation), which means 'valley' (cognate with English dale).[25][26][27]

Neanderthal 1 was known as the "Neanderthal cranium" or "Neanderthal skull" in anthropological literature, and the individual reconstructed on the basis of the skull was occasionally called "the Neanderthal man".[28] The binomial name Homo neanderthalensis – extending the name "Neanderthal man" from the individual type specimen to the entire species – was first proposed by the Anglo-Irish geologist William King in 1864, although that same year King changed his mind and thought that the Neanderthal fossil was distinct enough from humans to warrant a separate genus.[29] Nevertheless, King's name had priority over the proposal put forward in 1866 by Ernst Haeckel, Homo stupidus.[26] The practice of referring to "the Neanderthals" and "a Neanderthal" emerged in the popular literature of the 1920s.[30]

The German pronunciation of Neanderthaler and Neandertaler is [neˈandɐˌtʰaːlɐ] in the International Phonetic Alphabet. In British English, "Neanderthal" is pronounced with the /t/ as in German but different vowels (IPA: /niːˈændərtɑːl/).[31][32][33] In layman's American English, "Neanderthal" is pronounced with a /θ/ (the voiceless th as in thin) and /ɔ/ instead of the longer British /aː/ (IPA: /niːˈændərθɔːl/),[34] although scientists typically use the /t/ as in German.[35][36]

Classification edit

For some time, scientists have debated whether Neanderthals should be classified as Homo neanderthalensis or Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, the latter placing Neanderthals as a subspecies of H. sapiens.[37][38] Some morphological studies support the view that H. neanderthalensis is a separate species and not a subspecies.[39][40] Others, for example University of Cambridge Professor Paul Mellars, say "no evidence has been found of cultural interaction"[41] and evidence from mitochondrial DNA studies has been interpreted as evidence Neanderthals were not a subspecies of H. sapiens.[42]

Origin edit

The first humans with proto-Neanderthal traits are believed to have existed in Eurasia as early as 350,000–600,000 years ago[43] with the first "true Neanderthals" appearing between 200,000 and 250,000 years ago.[44] The exact date of their extinction had been disputed. However, in 2014, Thomas Higham of the University of Oxford performed the most comprehensive dating of Neanderthal bones and tools ever carried out, which demonstrated that Neanderthals died out in Europe between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago—this coincides with the start of a very cold period in Europe and is 5,000 years after Homo sapiens reached the continent. This was based on improved radiocarbon dating of materials from 40 sites in Western Europe.[45]

Comparison of the DNA of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens suggests that they diverged from a common ancestor between 350,000 and 400,000 years ago. This ancestor was probably Homo heidelbergensis. Heidelbergensis originated between 800,000 and 1,300,000 years ago, and continued until about 200,000 years ago. It ranged over Eastern and South Africa, Europe and Western Asia. Between 350,000 and 400,000 years ago the African branch is thought to have started evolving towards modern humans and the Eurasian branch towards Neanderthals. Scientists do not agree when Neanderthals can first be recognised in the fossil record, with dates ranging between 200,000 and 300,000 years BP.[46][47][48][49]

Discovery edit

Neanderthal skulls were first discovered in Engis Caves (fr), in what is now Belgium (1829) by Philippe-Charles Schmerling and in Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar, dubbed Gibraltar 1 (1848), both prior to the type specimen discovery in a limestone quarry of the Neander Valley in Erkrath near Düsseldorf in August 1856, three years before Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published.[50]

The type specimen, dubbed Neanderthal 1, consisted of a skull cap, two femora, three bones from the right arm, two from the left arm, part of the left ilium, fragments of a scapula, and ribs. The workers who recovered this material originally thought it to be the remains of a bear. They gave the material to amateur naturalist Johann Carl Fuhlrott, who turned the fossils over to anatomist Hermann Schaaffhausen.

To date, the bones of over 400 Neanderthals have been found.[51]

Timeline edit

- 1829: Neanderthal skulls were discovered in Engis, in present-day Belgium.

- 1848: Neanderthal skull Gibraltar 1 found in Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar. Called "an ancient human" at the time.

- 1856: Johann Karl Fuhlrott first recognized the fossil called "Neanderthal man", discovered in Neanderthal, a valley near Mettmann in what is now North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

- 1864: William King proposed the name Homo neanderthalensis at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, but then changed his mind and argued that Neanderthals were different enough from humans to warrant a separate genus, under the assumption that they were likely "incapable of moral and theositic conceptions."[29]

- 1880: The mandible of a Neanderthal child was found in a secure context and associated with cultural debris, including hearths, Mousterian tools, and bones of extinct animals.

- 1886: Two nearly perfect skeletons of a man and woman were found at Spy, Belgium at the depth of 16 ft with numerous Mousterian-type implements.

- 1899: Hundreds of Neanderthal bones were described in stratigraphic position in association with cultural remains and extinct animal bones.

- 1899: Sand excavation workers found bone fragments on a hill in Krapina, Croatia called Hušnjakovo brdo. Local Franciscan friar Dominik Antolković requested Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger to study the remains of bones and teeth that were found there.

- 1905: During the excavation in Krapina more than 5 000 items were found, of which 874 residue of human origin, including bones of prehistoric man and animals, artifacts.

- 1908: A nearly complete Neanderthal skeleton was discovered in association with Mousterian tools and bones of extinct animals.[clarification needed]

- 1925: Francis Turville-Petre finds the 'Galilee Man' or 'Galilee Skull' in the Zuttiyeh Cave in Wadi Amud in The British Mandate of Palestine (now Israel).

- 1926 Skull fragments of Gibraltar 2, a four-year-old Neanderthal girl, discovered by Dorothy Garrod.

- 1953–1957: Ralph Solecki uncovered nine Neanderthal skeletons in Shanidar Cave in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq.

- 1975: Erik Trinkaus' study of Neanderthal feet confirmed they walked like modern humans.

- 1987: Thermoluminescence results from Israeli fossils date Neanderthals at Kebara to 60,000 BP and humans at Qafzeh to 90,000 BP. These dates were confirmed by electron spin resonance (ESR) dates for Qafzeh (90,000 BP) and Es Skhul (80,000 BP).

- 1991: ESR dates showed the Tabun Neanderthal was contemporaneous with modern humans from Skhul and Qafzeh.

- 1993: 127,000-year-old DNA is found on the child of Sclayn, found in Scladina (fr), Belgium.

- 1997: Matthias Krings et al. are the first to amplify Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) using a specimen from Feldhofer grotto in the Neander valley.[52]

- 1998: A team led by pre-history archeologist João Zilhão discovered an early Upper Paleolithic human burial in Portugal, at Abrigo do Lagar Velho, which provided evidence of early modern humans from the west of the Iberian Peninsula. The remains, a largely complete skeleton of an approximately 4-year-old child, buried with pierced shell and red ochre, is dated to ca. 24,500 years BP.[53] The cranium, mandible, dentition, and postcrania present a mosaic of European early modern human and Neanderthal features.[53]

- 2000: Igor Ovchinnikov, Kirsten Liden, William Goodman et al. retrieved DNA from a Late Neanderthal infant from Mezmaiskaya Cave in the Caucasus.[54]

- 2005: The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology launched a project to reconstruct the Neanderthal genome, working with Connecticut-based 454 Life Sciences.[citation needed] In 2009, the Max Planck Institute announced the "first draft" of a complete Neanderthal genome is completed.[55]

- 2010: Comparison of Neanderthal genome with modern humans from Africa and Eurasia shows that 1–4% of modern non-African human genome might come from the Neanderthals.[56][17]

- 2010: Discovery of Neanderthal tools far away from the influence of H. sapiens indicate that the species might have been able to create and evolve tools on its own, and therefore be more intelligent than previously thought. Furthermore, it was proposed that the Neanderthals might be more closely related to Homo sapiens than previously thought and that may in fact be a subspecies of it.[57] Evidence has more recently emerged that these artifacts are probably of H. sapiens sapiens origin.[58]

- 2012: Charcoal found next to six paintings of seals in Nerja caves, Malaga, Spain, has been dated to between 42,300 and 43,500 years old. The paintings themselves will be dated in 2013, and if their pigment matches the date of the charcoal, they would be the oldest known cave paintings. José Luis Sanchidrián at the University of Cordoba, Spain believes the paintings are more likely to have been painted by Neanderthals than early modern humans.[59]

- 2013: A jawbone found in Italy had features intermediate between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens suggesting it could be a hybrid. The mitochondrial DNA is Neanderthal.[60]

- 2013: An international team of researchers reported evidence that Neanderthals practiced burial behavior and intentionally buried their dead.[20]

- 2014: Researchers at the University of Colorado Museum in Boulder report that Neanderthals were not less intelligent than modern humans and "that single-factor explanations for the disappearance of the Neandertals are not warranted any more."[61]

- 2014: Prof Thomas Higham of the University of Oxford performed the most comprehensive dating of Neanderthal bones and tools ever carried out, which demonstrated that Neanderthals died out in Europe between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago - this coincides with the start of a very cold period in Europe and is 5000 years after Homo sapiens reached the continent.[62]

Habitat and range edit

Early Neanderthals lived in the last glacial period for a span of about 100,000 years. Because of the damaging effects the glacial period had on the Neanderthal sites, not much is known about the early species. Countries where their remains are known include most of Europe south of the line of glaciation, roughly along the 50th parallel north. This includes most of Western Europe, the south coast of Great Britain,[63] Central Europe, the Carpathians, and the Balkans,[64] some sites in Ukraine and in western Russia, Central and Northern Asia up to the Altai Mountains, and Western Asia from the Levant up to the Indus River. It is estimated that the total Neanderthal population across this habitat range numbered at around 70,000 at its peak.[65]

Neanderthal fossils have not been found to date in Africa, but there have been finds close to North Africa, both on Gibraltar and in the Levant. At some Levantine sites, Neanderthal remains date from after the same sites were vacated by modern humans. Mammal fossils of the same time period show cold-adapted animals were present alongside these Neanderthals in this region of the Eastern Mediterranean. This implies Neanderthals were better adapted biologically to cold weather than modern humans and at times displaced them in parts of the Middle East when the climate got cold enough. However this has been disputed recently through studies of their cranial morphology and sinuses. Some scholars have also posited that Neanderthals could be an Asian species which expanded into Europe, making Neanderthals a tropical species rather than cold adaptive.[66][67]

Homo sapiens sapiens appears to have been the only human type in the Nile River Valley during these periods, and Neanderthals are not known to have ever lived south-west of present-day Israel. When climate change caused warmer temperatures, the Neanderthal range likewise retreated to the north, along with the cold-adapted species of mammals. Apparently these weather-induced population shifts took place before modern people secured competitive advantages over the Neanderthal, as these shifts in range took place well over ten thousand years before modern people totally replaced the Neanderthal, despite the recent evidence of some successful interbreeding.[66]

Separate developments in the human line, in other regions such as Southern Africa, somewhat resembled the Eurasian Neanderthals, but these people were not Neanderthals. One such example is Rhodesian Man (Homo rhodesiensis), who existed long before any classic Eurasian Neanderthals, but had a more modern set of teeth. Some H. rhodesiensis populations appeared to be on the road to modern H. sapiens sapiens. At any rate, the populations in Eurasia underwent more and more "Neanderthalization" as time went on. There is some argument that H. rhodesiensis in general was ancestral to both modern humans and Neanderthals, and that at some point the two populations went their separate ways, but this supposes that H. rhodesiensis goes back to around 600,000 years ago.

To date, no intimate connection has been found between these similar archaic people and the Eurasian Neanderthals, at least during the same time as H. rhodesiensis seems to have lived about 600,000 years ago, long before the time of classic Neanderthals. This said, some researchers think that H. rhodesiensis may have lived much later than this period, depending on the method used to date the fossils, leaving this issue open to debate. Some H. rhodesiensis features, like the large brow ridge, may have been caused by convergent evolution.

It appears incorrect, based on present research and known fossil finds, to refer to any fossils outside Eurasia as true Neanderthals. They had a known range that possibly extended as far east as the Altai Mountains, but not farther to the east or south, and apparently not into Africa. At any rate, in North-East Africa the land immediately south of the Neanderthal range was possessed by modern humans Homo sapiens idaltu or Homo sapiens, since at least 160,000 years before the present. 160,000-year-old hominid fossils at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco were previously thought to be Neanderthal, but it is now clear that they are early modern humans.[68]

Classic Neanderthal fossils have been found over a large area, from northern Germany to Israel and Mediterranean countries like Spain[69] and Italy[70] in the south and from England and Portugal in the west to Uzbekistan in the east. This area probably was not occupied all at the same time. The northern border of their range, in particular, would have contracted frequently with the onset of cold periods. On the other hand, the northern border of their range as represented by fossils may not be the real northern border of the area they occupied, since Middle Palaeolithic-looking artifacts have been found even farther north, up to 60° N, on the Russian plain.[71] Recent evidence has extended the Neanderthal range by about 1,250 miles (2,010 km) east into southern Siberia's Altai Mountains.[72][73]

Anatomy edit

Neanderthal anatomy differed from modern humans in that they had a more robust build and distinctive morphological features, especially on the cranium, which gradually accumulated more derived aspects as it was described by Marcellin Boule,[74] particularly in certain isolated geographic regions. These include shorter limb proportions, a wider, barrel-shaped rib cage, a reduced chin and, perhaps most notably, a large nose, which was much larger in both length and width, and started somewhat higher on the face, than in modern humans.[44] Evidence suggests they were much stronger than modern humans, with particularly strong arms and hands,[75][76] while they were comparable in height; based on 45 long bones from at most 14 males and 7 females, Neanderthal males averaged 164–168 cm (65–66 in) and females 152–156 cm (60–61 in) tall.[16] Samples of 26 specimens in 2010 found an average weight of 77.6 kg (171 lb) for males and 66.4 kg (146 lb) for females.[77] A 2007 genetic study suggested some Neanderthals may have had red hair and blond hair, along with a light skin tone.[78]

A 2013 study of Neanderthal skulls suggests that their eyesight may have been better than that of modern humans, owing to larger eye sockets and larger areas of the brain devoted to vision.[79] Neanderthals are known for their large cranial capacity, which at 1600 cm3 is larger on average than that of modern humans. One study has found that Neanderthal brains were more asymmetric than other hominid brains.[80] In 2008, a group of scientists produced a study using three-dimensional computer-assisted reconstructions of Neanderthal infants based on fossils found in Russia and Syria. It indicated that Neanderthal and modern human brains were the same size at birth, but that by adulthood, the Neanderthal brain was larger than the modern human brain.[81]

Behavior edit

Neanderthals made advanced tools,[82] probably had a language (the nature of which is debated and likely unknowable) and lived in complex social groups. The Molodova archaeological site in eastern Ukraine suggests some Neanderthals built dwellings using animal bones. A building was made of mammoth skulls, jaws, tusks and leg bones, and had 25 hearths inside.[83]

Circumstantial evidence suggests Neanderthals may have been building some form of watercraft since the Middle Paleolithic.[84][85] Scientists have speculated that these watercraft may have been similar to dugout canoes, which are among the oldest known boats in the archaeological record.[85] Mousterian stone tools discovered on the southern Ionian Islands suggests that Neanderthals were sailing the Mediterranean Sea as early as 110,000 years BP.[86][87] Quartz hand-axes, three-sided picks, and stone cleavers from Crete have also been recovered that date back about 170,000 years BP.[88]

It was once thought that Neanderthals lacked the sophistication for hunting, perhaps scavenging meat from carcasses,[44] but increasing evidence suggests they were apex predators,[89][90] capable of bringing down a wide range of prey from red deer, reindeer, ibex and wild boar, to larger animals such as aurochs and even, on occasion, mammoth, straight-tusked elephant and rhinoceros.[44][91] However, while largely carnivorous,[92][93] new studies indicate Neanderthals also had cooked vegetables in their diet.[90][94] In 2010, an isotope analysis of Neanderthal teeth found traces of cooked vegetable matter, and more recently a 2014 study of Neanderthal coprolites (fossilized feces) found substantial amounts of plant matter, contradicting the earlier belief they were exclusively (or almost exclusively) carnivorous.[92][95]

The size and distribution of Neanderthal sites, along with genetic evidence, suggests Neanderthals lived in much smaller and more sparsely distributed groups than their Homo sapiens contemporaries.[96][97] Some experts suggest that this disparity alone was a major contributing factor to their ultimate replacement by Homo sapiens, which may have outnumbered them by as much as 9 to 1 according to some estimates.[96] Their lower population density may have also increased Neanderthal susceptibility to mutations caused by inbreeding,[97] and may have discouraged the evolution of cognitive abilities needed to deal with strangers.[79]

Violence edit

The St. Césaire 1 skeleton discovered in 1979 at La Roche à Pierrot, France, showed a healed fracture on top of the skull apparently caused by a deep blade wound. Researchers have taken this as evidence of the presence of interpersonal violence among the Neanderthals.[98]

Genome edit

Early investigations concentrated on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which, owing to strictly matrilineal inheritance and subsequent vulnerability to genetic drift, is of limited value in evaluating the possibility of interbreeding of Neanderthals with Cro-Magnon people.

In 1997, geneticists were able to extract a short sequence of DNA from Neanderthal bones.[99] The extraction of mtDNA from a second specimen was reported in 2000, and showed no sign of modern human descent from Neanderthals.[54]

In July 2006, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and 454 Life Sciences announced that they would sequence the Neanderthal genome over the next two years. This genome was expected to be roughly the size of the human genome, three-billion base pairs, and share most of its genes. It was hoped the comparison would expand understanding of Neanderthals, as well as the evolution of humans and human brains.[100]

Svante Pääbo has tested more than 70 Neanderthal specimens. The Neanderthal genome is almost the same size as the human genome and is identical to ours to a level of 99.7% by comparing the accurate order of the nitrogenous bases in the double nucleotide chain.[101] From mtDNA analysis estimates, the two species shared a common ancestor about 500,000 years ago. An article[102] appearing in the journal Nature has calculated the species diverged about 516,000 years ago, whereas fossil records show a time of about 400,000 years ago.[103] A 2007 study pushes the point of divergence back to around 800,000 years ago.[104]

Edward Rubin of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory states recent genome testing of Neanderthals suggests human and Neanderthal DNA are some 99.5% to nearly 99.9% identical.[105][106]

On 16 November 2006, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory issued a press release suggesting Neanderthals and ancient humans probably did not interbreed.[107] Edward M. Rubin, director of the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Joint Genome Institute (JGI), sequenced a fraction (0.00002) of genomic nuclear DNA (nDNA) from a 38,000-year-old Vindia Neanderthal femur. They calculated the common ancestor to be about 353,000 years ago, and a complete separation of the ancestors of the species about 188,000 years ago.[108]

Their results show the genomes of modern humans and Neanderthals are at least 99.5% identical, but despite this genetic similarity, and despite the two species having coexisted in the same geographic region for thousands of years, Rubin and his team did not find any evidence of any significant interbreeding between the two. Rubin said, "While unable to definitively conclude that interbreeding between the two species of humans did not occur, analysis of the nuclear DNA from the Neanderthal suggests the low likelihood of it having occurred at any appreciable level."[108]

In 2008 Richard E. Green et al. from Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, published the full sequence of Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and suggested "Neanderthals had a long-term effective population size smaller than that of modern humans."[109] Writing in Nature about Green et al.'s findings, James Morgan asserted the mtDNA sequence contained clues that Neanderthals lived in "small and isolated populations, and probably did not interbreed with their human neighbours."[110][111]

In the same publication, it was disclosed by Svante Pääbo that in the previous work at the Max Planck Institute, "Contamination was indeed an issue," and they eventually realized that 11% of their sample was modern human DNA.[112][113] Since then, more of the preparation work has been done in clean areas and 4-base pair 'tags' have been added to the DNA as soon as it is extracted so the Neanderthal DNA can be identified.

With 3 billion nucleotides sequenced, analysis of about ⅓ showed no sign of admixture between modern humans and Neanderthals, according to Pääbo. This concurred with the work of Noonan from two years earlier. The variant of microcephalin common outside Africa, which was suggested to be of Neanderthal origin and responsible for rapid brain growth in humans, was not found in Neanderthals. Nor was the MAPT variant, a very old variant found primarily in Europeans.[112]

However, an analysis of a first draft of the Neanderthal genome by the same team released in May 2010 indicates interbreeding may have occurred.[56][17] "Those of us who live outside Africa carry a little Neanderthal DNA in us," said Pääbo, who led the study. "The proportion of Neanderthal-inherited genetic material is about 1 to 4 percent. It is a small but very real proportion of ancestry in non-Africans today," says Dr. David Reich of Harvard Medical School, who worked on the study. This research compared the genome of the Neanderthals to five modern humans from China, France, sub-Saharan Africa, and Papua New Guinea. The finding is that about 1 to 4 percent of the genes of the non-Africans came from Neanderthals, compared to the baseline defined by the two Africans.[56]

This indicates a gene flow from Neanderthals to modern humans, i.e., interbreeding between the two populations. Since the three non-African genomes show a similar proportion of Neanderthal sequences, the interbreeding must have occurred early in the migration of modern humans out of Africa, perhaps in the Middle East. No evidence for gene flow in the direction from modern humans to Neanderthals was found. Gene flow from modern humans to Neanderthals would not be expected if contact occurred between a small colonizing population of modern humans and a much larger resident population of Neanderthals. A very limited amount of interbreeding could explain the findings, if it occurred early enough in the colonization process.[56]

While interbreeding is viewed as the most parsimonious interpretation of the genetic discoveries, the authors point out they cannot conclusively rule out an alternative scenario, in which the source population of non-African modern humans was already more closely related to Neanderthals than other Africans were, because of ancient genetic divisions within Africa.[56] Other studies carried out since the sequencing of the Neanderthal genome have cast doubt on the level of admixture between Neanderthals and modern humans, or even as to whether the species interbred at all. One study has asserted that the presence of Neanderthal or other archaic human genetic markers can be attributed to shared ancestral traits between the species originating from a 500,000-year-old common ancestor.[114][115][116]

Among the genes shown to differ between present-day humans and Neanderthals were RPTN, SPAG17, CAN15, TTF1 and PCD16.[56]

Extinction hypotheses edit

As the 2014 study by Thomas Higham of Neanderthal bones and tools indicates that Neanderthals died out in Europe between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago, and that Homo sapiens arrived in Europe between 45,000 and 43,000 years ago, it is now apparent that the two different human populations shared Europe for as long as 5,000 years.[62] The exact nature of biological and cultural interaction between Neanderthals and other human groups has been contested.[117]

Possible scenarios for the extinction of the Neanderthals are:

- Neanderthals were a separate species from modern humans, and became extinct (because of climate change or interaction with humans) and were replaced by modern humans moving into their habitat between 45,000 and 40,000 years ago.[118] Jared Diamond has suggested a scenario of violent conflict and displacement.[119]

- Neanderthals were a contemporary subspecies that bred with modern humans and disappeared through absorption (interbreeding theory).

As Paul Jordan notes: "A natural sympathy for the underdog and the disadvantaged lends a sad poignancy to the fate of the Neanderthal folk, however it came about." Jordan, though, does say that there was perhaps interbreeding to some extent, but that populations that remained totally Neanderthal were probably out-competed and marginalized to extinction by the Aurignacians.[66]

Climate change edit

About 55,000 years ago, the weather began to fluctuate wildly from extreme cold conditions to mild cold and back in a matter of a few decades. Neanderthal bodies were well suited for survival in a cold climate—their barrel chests and stocky limbs stored body heat better than the Cro-Magnons. However, the rapid fluctuations of weather caused ecological changes to which the Neanderthals could not adapt; familiar plants and animals would be replaced by completely different ones within a lifetime. Neanderthals' ambush techniques would have failed as grasslands replaced trees. Neanderthals died out in Europe between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago which coincides with the start of a very cold period.[62][121] Raw material sourcing and the examination of faunal remains by Adler et al. (2006) in the southern Caucasus region suggest that modern humans may have had a survival advantage during this period, being able to use social networks to acquire resources from a greater area. They found that in both the Late Middle Palaeolithic and Early Upper Palaeolithic more than 95% of stone artifacts were drawn from local material, suggesting Neanderthals were restricted to more local resources. Furthermore, excavations at Ortvale Klde Rockshelter discovered that there was a clear break between the Late Middle Paleolithic and the Early Upper Paleolithic lithic assemblages, which were attributed to Neanderthals and modern humans respectively. This would suggest that modern humans came in and replaced Neanderthals, rather than a slow shift or integration occurring in this region. [122]

Studies on Neanderthal body structures have shown that they needed more energy to survive than any other species of hominid. Their energy needs were up to 100 to 350 kcal (420 to 1,460 kJ) more per day comparing to projected anatomically modern human males weighing 68.5 kg (151 lb) and females 59.2 kg (131 lb).[123] When food became scarce, this difference may have played a major role in the Neanderthals' extinction.[121]

Coexistence with Homo sapiens edit

In November 2011 tests conducted at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit in England on what were previously thought to be Neanderthal baby teeth, which had been unearthed in 1964 from the Grotta del Cavallo in Italy, were identified as the oldest modern human remains discovered anywhere in Europe, dating from between 43,000 and 45,000 years ago.[124] Given that the 2014 study by Thomas Higham of Neanderthal bones and tools indicates that Neanderthals died out in Europe between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago, the two different human populations shared Europe for as long as 5,000 years.[62] The exact nature of biological and cultural interaction between Neanderthals and other human groups has been contested.[117]

Modern humans co-existed with them in Europe starting around 35,000 years, perhaps even earlier. Neanderthals inhabited that continent for a long period of time before the arrival of modern humans. H. sapiens may have introduced a disease that contributed to the extinction of Neanderthals, and that may be added to other recent explanations for their extinction. When Neanderthal ancestors left Africa roughly 100,000 years earlier they adapted to the pathogens in their European environment, unlike modern humans who adapted to African pathogens. This transcontinental movement is known as the Out of Africa model. If contact between humans and Neanderthals occurred in Europe and Asia the first contact may have been devastating to the Neanderthal population, because they would have little if any immunity to the African pathogens. More recent historical events in Eurasia and the Americas show a similar pattern, where the unintentional introduction of viral, or bacterial pathogens to unprepared populations has led to mass mortality and local population extinction.[125] The most well known example of this is the arrival of Christopher Columbus to the New World, which brought and introduced foreign diseases when he and his crew arrived to a native population who had no immunity.

Anthropologist Pat Shipman, of Pennsylvania State University, suggested that domestication of the dog could have played a role in neanderthals' extinction.[126]

Interbreeding hypotheses edit

An alternative to extinction is that Neanderthals were absorbed into the Cro-Magnon population by interbreeding. This would be counter to strict versions of the Recent African Origin, since it would imply that at least part of the genome of Europeans would descend from Neanderthals.

Hans Peder Steensby, while strongly emphasising that all modern humans are of mixed origins, proposed the interbreeding hypothesis in 1907, in the article Race studies in Denmark.[128] He held that this would best fit current observations, and attacked the widespread idea that Neanderthals were ape-like or inferior.

The most vocal proponent of the hybridization hypothesis is Erik Trinkaus of Washington University.[129] Trinkaus claims various fossils as products of hybridized populations, including the child of Lagar Velho, a skeleton found at Lagar Velho in Portugal.[130][131] In a 2006 publication co-authored by Trinkaus, the fossils found in 1952 in the cave of Peștera Muierii, Romania, are likewise claimed as descendants of previously hybridized populations.[132]

Genetic research has asserted that some admixture took place.[133] The genomes of all non-Africans include portions that are of Neanderthal origin,[134][135] due to interbreeding between Neanderthals and the ancestors of Eurasians in Northern Africa or the Middle East prior to their spread. Rather than absorption of the Neanderthal population, this gene flow appears to have been of limited duration and limited extent. An estimated 1 to 4 percent of the DNA in Europeans and Asians (French, Chinese and Papua probands) is non-modern, and shared with ancient Neanderthal DNA rather than with Sub-Saharan Africans (Yoruba people and San probands).[56] Ötzi the iceman, Europe's oldest preserved mummy, was found to possess an even higher percentage of Neanderthal ancestry.[136] Recent findings suggest there may be even more Neanderthal genes in non-African humans than previously expected: approximately 20% of the Neanderthal gene pool was present in a broad sampling of non-African individuals, though each individual's genome was on average only 2% Neanderthal.[137]

More recent genetic studies seem to suggest that modern humans may have mated with "at least two groups" of ancient humans: Neanderthals and Denisovans.[138] Some researchers suggest admixture of 3.4%-7.9% in modern humans of non-African ancestry, rejecting the hypothesis of ancestral population structure.[139] Detractors have argued and continue to argue that the signal of Neanderthal interbreeding may be due to ancient African substructure, meaning that the similarity is only a remnant of a common ancestor of both Neanderthals and modern humans and not the result of interbreeding.[140][141] John D. Hawks has argued that the genetic similarity to Neanderthals may indeed be the result of both structure and interbreeding, as opposed to just one or the other.[142]

While modern humans share some nuclear DNA with the extinct Neanderthals, the two species do not share any mitochondrial DNA,[143] which in primates is always maternally transmitted. This observation has prompted the hypothesis that whereas female humans interbreeding with male Neanderthals were able to generate fertile offspring, the progeny of female Neanderthals who mated with male humans were either rare, absent or sterile.[144] However, some researchers have argued that there is evidence of possible interbreeding between female Neanderthals and male modern humans.[145][146]

Specimens edit

Notable specimens edit

- Neanderthal 1: The first Neanderthal specimen found during an archaeological dig in August 1856. It was discovered in a limestone quarry at the Feldhofer grotto in Neanderthal, Germany. The find consisted of a skull cap, two femora, three right arm bones, two left arm bones, ilium, and fragments of a scapula and ribs.

- La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1: Called the Old Man, a fossilized skull discovered in La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France, by A. and J. Bouyssonie, and L. Bardon in 1908. Characteristics include a low vaulted cranium and large browridge typical of Neanderthals. Estimated to be about 60,000 years old, the specimen was severely arthritic and had lost all his teeth, with evidence of healing. For him to have lived on would have required that someone process his food for him, one of the earliest examples of Neanderthal altruism (similar to Shanidar I.)

- La Ferrassie 1: A fossilized skull discovered in La Ferrassie, France, by R. Capitan in 1909. It is estimated to be 70,000 years old. Its characteristics include a large occipital bun, low-vaulted cranium and heavily worn teeth.

- Le Moustier: A fossilized skull, discovered in 1909, at the archaeological site in Peyzac-le-Moustier, Dordogne, France. The Mousterian tool culture is named after Le Moustier. The skull, estimated to be less than 45,000 years old, includes a large nasal cavity and a somewhat less developed brow ridge and occipital bun as might be expected in a juvenile.

- Shanidar Cave: Found in the Zagros Mountains in (Iraqi Kurdistan); a total of nine skeletons found believed to have lived in the Middle Paleolithic. One of the nine remains was missing part of its right arm, which is theorized to have been broken off or amputated. The find is also significant because it shows that stone tools were present among this tribe's culture. One of the skeletons was originally thought to have been buried with flowers, signifying that some type of burial ceremony may have occurred. This is no longer considered to be the case, and Paul B. Pettitt has stated that the "deliberate placement of flowers has now been convincingly eliminated", noting that "A recent examination of the microfauna from the strata into which the grave was cut suggests that the pollen was deposited by the burrowing rodent Meriones tersicus, which is common in the Shanidar microfauna and whose burrowing activity can be observed today".[147]

- Amud 1: Fossilized remains of an adult Neanderthal, dated to roughly 45,000 years ago, and one of several found in a cave at Nahal Amud, Israel, at least some of which may have been deliberately buried. A particularly notable feature of this find is its cranial capacity, which, at 1,740 cm3, is among the largest known for any hominid, living or extinct.[44][148]

Chronology edit

This section describes bones with Neanderthal traits in chronological order.

Mixed with H. heidelbergensis traits edit

- > 350 ka: Sima de los Huesos c. 500:350 ka ago[149][150]

- 350–200 ka: Pontnewydd 225 ka ago.

- 200–135 ka: Atapuerca,[151] Vértesszőlős, Ehringsdorf, Casal de'Pazzi, Biache, La Chaise, Montmaurin, Prince, Lazaret, Fontéchevade

Typical H. neanderthalensis traits edit

- 135–45 ka: Krapina, Saccopastore skulls, Malarnaud, Altamura, Gánovce, Denisova, Okladnikov Altai, Pech de l'Azé, Tabun 120 ka – 100±5 ka,[152] Qafzeh9 100, Shanidar 1 to 9 80–60 ka, La Ferrassie 1 70 ka, Kebara 60 ka, Régourdou, Mt. Circeo, Combe Grenal, Erd 50 ka, La Chapelle-aux Saints 1 60 ka, Amud I 53±8 ka,[153][154] Teshik-Tash.

- 45–35 ka: Le Moustier 45 ka, Feldhofer 42 ka, La Quina, l'Horus, Hortus, Kulna, Šipka, Saint Césaire, Bacho Kiro, El Castillo, Bañolas, Arcy-sur-Cure.[155]

- < 35 ka: Châtelperron, Figueira Brava, Zafarraya 30 ka,[155] Vogelherd 3?,[verification needed][156] Vindija 32,400 ± 800 14C B.P.[157] (Vi-208 31,390 ± 220, Vi-207 32,400 ± 1,800 14C B.P.),[157] Velika Pećina,

Homo sapiens with some neanderthal-like archaic traits edit

- < 35 Pestera cu Oase 35 ka, Mladeč 31 ka, Pestera Muierii 30 ka (n/s),[158] Lapedo Child 24.5 ka.

Popular culture edit

Neanderthals have been portrayed in popular culture including appearances in literature, visual media and comedy, often in an unflattering and inaccurate light.

Early artistic reconstructions mostly presented Neanderthals as beastly creatures, emphasizing hairiness and rough, dark complexion.[159] More recent reconstructions acknowledge that because of the lineage evolution in European latitude there is reason to believe that Neanderthals were fair-skinned and probably with no more facial hair than modern man. Archaeological evidence exists indicating that they probably communicated by speech and used tools. Artist renderings and reconstructions of Neanderthals have become much more intelligent-looking and closely resembling modern humans.[160][161]

See also edit

- Abrigo do Lagar Velho — More about "the Lapedo child"

- Almas: wild man of Mongolia

- Basajaun

- Altamura Man

- Roca dels Bous (archaeological site)

- Biological anthropology

- Caveman

- Denisova hominin another Homo species that may have interbred with Neanderthals

- Early human migrations

- Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

- Neanderthal Museum

- Neanderthals of Gibraltar

- Pleistocene megafauna

- Species problem

Lists:

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of human evolution fossils (with images)

- List of Neanderthal sites

References edit

- ^ [1]

- ^ Dictionary of Anthropology - Charles Winick - Google Books. Books.google.ca (1956-12-18). Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ^ Bibliography of Fossil Vertebrates 1954-1958 - C.L. Camp, H.J. Allison, and R.H. Nichols - Google Books. Books.google.ca. Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ^ "Neanderthal in ODE". Oxford Dictionaries.

- ^ ""Neanderthal" in Random House Dictionary (US) & Collins Dictionary (UK)". Dictionary.com.

- ^ Colin P.T. Baillie; University of California, Berkeley. "Neandertals: Unique from Humans, or Uniquely Human?" (PDF). berkeley.edu.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History. "Ancient DNA and Neanderthals". si.edu.

- ^ Eran Meshorer, Liran Carmel; et al. (2014). "Reconstructing the DNA Methylation Maps of the Neandertal and the Denisovan". Science. 344 (6183): 523–527. doi:10.1126/science.1250368. PMID 24786081.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Hublin, J. J. (2009). "The origin of Neandertals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16022–7. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616022H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904119106. JSTOR 40485013. PMC 2752594. PMID 19805257.

- ^ Harvati, K.; Frost, S.R.; McNulty, K.P. (2004). "Neanderthal taxonomy reconsidered: implications of 3D primate models of intra- and interspecific differences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (5): 1147–52. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308085100. PMC 337021. PMID 14745010. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- ^ Skinner, A., B. Blackwell, R. Long, M.R. Seronie-Vivien, A.-M. Tillier and J. Blickstein; New ESR dates for a new bone-bearing layer at Pradayrol, Lot, France; Paleoanthropology Society March 28, 2007

- ^ Finlayson, C; Pacheco, Fg; Rodríguez-Vidal, J; Fa, Da; Gutierrez, López, Jm; Santiago, Pérez, A; Finlayson, G; Allue, E; Baena, Preysler, J; Cáceres, I; Carrión, Js; Fernández, Jalvo, Y; Gleed-Owen, Cp; Jimenez, Espejo, Fj; López, P; López, Sáez, Ja; Riquelme, Cantal, Ja; Sánchez, Marco, A; Guzman, Fg; Brown, K; Fuentes, N; Valarino, Ca; Villalpando, A; Stringer, Cb; Martinez, Ruiz, F; Sakamoto, T (October 2006). "Late survival of Neanderthals at the southernmost extreme of Europe". Nature. 443 (7113): 850–3. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..850F. doi:10.1038/nature05195. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16971951.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Outside Europe, Mousterian tools were made by both Neanderthals and early modern Homo sapiens. (Donald Johanson & Blake Edgar (2006) From Lucy to Language, Simon & Schuster, p. 272 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-VKEjAbpggcC&pg=PT272&lpg=PT2720&focus=viewport&vq=Mousterian+tools&dq=From+Lucy+to+Language+%22Mousterian+tools%22#v=onepage&q=Mousterian%20tools&f=false)

- ^ "Neanderthal man". infoplease.

- ^ Homo neanderthalensis, Archaeologyinfo.com. Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ^ a b Helmuth H (1998). "Body height, body mass and surface area of the Neanderthals". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie. 82 (1): 1–12. PMID 9850627.

- ^ a b c Rincon, Paul (2010-05-06). "Neanderthal genes 'survive in us'". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

{{cite news}}: External link in|work= - ^ Fu, Qiaomei; Li, Heng; Moorjani, Priya; Jay, Flora; Slepchenko, Sergey M.; Bondarev, Aleksei A.; Johnson, Philip L. F.; Aximu-Petri, Ayinuer; Prüfer, Kay; De Filippo, Cesare; Meyer, Matthias; Zwyns, Nicolas; Salazar-García, Domingo C.; Kuzmin, Yaroslav V.; Keates, Susan G.; Kosintsev, Pavel A.; Razhev, Dmitry I.; Richards, Michael P.; Peristov, Nikolai V.; Lachmann, Michael; Douka, Katerina; Higham, Thomas F. G.; Slatkin, Montgomery; Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Reich, David; Kelso, Janet; Viola, T. Bence; Pääbo, Svante (23 October 2014). "Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia". Nature. 514 (7523): 445–449. doi:10.1038/nature13810. hdl:10550/42071. PMC 4753769. PMID 25341783.

- ^ Brahic, Catherine. "Humanity's forgotten return to Africa revealed in DNA", The New Scientist (February 3, 2014).

- ^ a b Wilford, John Noble (December 16, 2013). "Neanderthals and the Dead". New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ^ http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/neanderthal-genes-found-in-modern-humans/2014/01/29/f7f81852-8774-11e3-a5bd-844629433ba3_story.html

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (December 18, 2013). "Toe Fossil Provides Complete Neanderthal Genome". New York Times. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ Prüfer, Kay; Racimo, Fernando; Patterson, Nick; Jay, Flora; Sankararaman, Sriram; Sawyer, Susanna; Heinze, Anja; Renaud, Gabriel; Sudmant, Peter H.; De Filippo, Cesare; Li, Heng; Mallick, Swapan; Dannemann, Michael; Fu, Qiaomei; Kircher, Martin; Kuhlwilm, Martin; Lachmann, Michael; Meyer, Matthias; Ongyerth, Matthias; Siebauer, Michael; Theunert, Christoph; Tandon, Arti; Moorjani, Priya; Pickrell, Joseph; Mullikin, James C.; Vohr, Samuel H.; Green, Richard E.; Hellmann, Ines; Johnson, Philip L. F.; Blanche, Hélène (2013). "The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains". Nature. 505 (7481): 43–49. doi:10.1038/nature12886. PMC 4031459. PMID 24352235.

- ^ The valley is named after Joachim Neander, a 17th-century German pastor and hymnist. His name happens to be a Greek translation of the German Neumann (lit. "Newman"), but neither he nor his name had anything to do with paleontology before the discovery of the fossils.

- ^ Tal after the German spelling reform of 1901, whence the German name Neandertal for both the valley and species.

- ^ a b Howell, F. Clark (December 1957). "The Evolutionary Significance of Variation and Varieties of 'Neanderthal' Man". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 32 (4): 330–47. doi:10.1086/401978. JSTOR 2816956. PMID 13506025.

- ^ Foley, Tim. TalkOrigins Archive. "Neanderthal or Neandertal?". 2005.

- ^ Inter alia, Vogt, Karl C. & al. "Lectures on man: his place in creation, and in the history of the earth", Publications of the Anthropological Society of London, p.302 & 473. Longman, Green, Longman, & Roberts (1864).

- ^ a b King, William (Jan 1864). "The Reputed Fossil Man of the Neanderthal" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Science. 1: 96.

- ^ Inter alia, Boys' Life, p. 18. January 1924.

- ^ The Oxford Illustrated Dictionary. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. 1976 [1975]. p. 564.

(tahl)

- ^ "Neanderthal adjective - definition in British English Dictionary & Thesaurus - Cambridge Dictionary Online". Dictionary.cambridge.org. 2013-01-08. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ^ "Oxford Learner's Dictionaries - Find pronunciation, clear meanings and definitions of words at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com".

- ^ "Neanderthal | Define Neanderthal at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ^ Kurtén, Björn (10 October 1995). Dance of the Tiger: A Novel of the Ice Age. University of California Press. pp. xxi. ISBN 0-520-20277-5. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Pollet, Carl J. (September 21, 1991). "…And Etymology". Science News. 140 (12): 191. doi:10.2307/3975867. JSTOR 3975867.

- ^ Tattersall, Ian; Schwartz, Jeffrey H. (1999). "Hominids and hybrids: The place of Neanderthals in human evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (13): 7117–9. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.7117T. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7117. JSTOR 48019. PMC 33580. PMID 10377375.

- ^ Duarte, Cidália; Mauricio, João; Pettitt, Paul B.; Souto, Pedro; Trinkaus, Erik; Van Der Plicht, Hans; Zilhao, João (1999). "The early Upper Paleolithic human skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and modern human emergence in Iberia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (13): 7604–9. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.7604D. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7604. JSTOR 48106. PMC 22133. PMID 10377462.

- ^ Harvati, K.; Frost, S.R.; McNulty, K.P. (February 2004). "Neanderthal taxonomy reconsidered: Implications of 3D primate models of intra- and interspecific differences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (5): 1147–52. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.1147H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308085100. PMC 337021. PMID 14745010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Research supports Neanderthals as a separate species". Archaeology News from Past Horizons.

- ^ "Modern humans, Neanderthals shared earth for 1,000 years". ABC News (Australia). 1 September 2005. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- ^ Hedges SB (December 2000). "Human evolution. A start for population genomics". Nature. 408 (6813): 652–3. doi:10.1038/35047193. PMID 11130051.

- ^ Bischoff, James L.; Shamp, Donald D.; Aramburu, Arantza; Arsuaga, Juan Luis; Carbonell, Eudald; Bermudez de Castro, J.M. (2003). "The Sima de los Huesos Hominids Date to Beyond U/Th Equilibrium (>350kyr) and Perhaps to 400–500kyr: New Radiometric Dates". Journal of Archaeological Science. 30 (3): 275–80. doi:10.1006/jasc.2002.0834.

- ^ a b c d e Papagianni, Dmitra; Morse, Michael (2013). The Neanderthals Rediscovered. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05177-1.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (20 August 2014). "New dates rewrite Neanderthal story". BBC. Archived from the original on 2015-02-10.

- ^ "Homo heidelbergensis: Evolutionary Tree". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Stringer, Chris. "The Ancient Human Occupation of Britain" (PDF). Natural History Museum, London. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Stringer, Chris (2011). The Origin of our Species. Penguin. pp. 26–29, 202. ISBN 978-0-141-03720-2.

- ^ Johansson, Donald; Edgar, Blake (2006). From Lucy to Language. Simon & Schuster. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7432-8064-8.

- ^ "Homo neanderthalensis". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ "New Evidence On The Role Of Climate In Neanderthal Extinction". Science Daily.

- ^ Krings, M; Stone, A; Schmitz, Rw; Krainitzki, H; Stoneking, M; Pääbo, S (July 1997). "Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans". Cell. 90 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80310-4. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0025-0960-8. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 9230299.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Duarte; Maurício, J; Pettitt, PB; Souto, P; Trinkaus, E; Van Der Plicht, H; Zilhão, J; et al. (1999). "The early Upper Paleolithic human skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and modern human emergence in the Iberian Peninsula". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (13). PNAS: 7604–7609. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.7604D. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7604. PMC 22133. PMID 10377462. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b Ovchinnikov, Iv; Götherström, A; Romanova, Gp; Kharitonov, Vm; Lidén, K; Goodwin, W (March 2000). "Molecular analysis of Neanderthal DNA from the northern Caucasus". Nature. 404 (6777): 490–3. doi:10.1038/35006625. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 10761915.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morgan, James (12 February 2009). "Neanderthals 'distinct from us'". BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Green, Richard E.; Krause, Johannes; Briggs, Adrian W.; Maricic, Tomislav; Stenzel, Udo; Kircher, Martin; Patterson, Nick; Li, Heng; Zhai, Weiwei; Fritz, Markus Hsi-Yang; Hansen, Nancy F.; Durand, Eric Y.; Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo; Jensen, Jeffrey D.; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Alkan, Can; Prüfer, Kay; Meyer, Matthias; Burbano, Hernán A.; Good, Jeffrey M.; Schultz, Rigo; Aximu-Petri, Ayinuer; Butthof, Anne; Höber, Barbara; Höffner, Barbara; Siegemund, Madlen; Weihmann, Antje; Nusbaum, Chad; Lander, Eric S.; Russ, Carsten (2010). "A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome". Science. 328 (5979): 710–22. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..710G. doi:10.1126/science.1188021. PMC 5100745. PMID 20448178.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ Benazzi, S.; Douka, K.; Fornai, C.; Bauer, C. C.; Kullmer, O.; Svoboda, J. Í.; Pap, I.; Mallegni, F.; Bayle, P.; Coquerelle, M.; Condemi, S.; Ronchitelli, A.; Harvati, K.; Weber, G. W. (2011). "Early dispersal of modern humans in Europe and implications for Neanderthal behaviour". Nature. 479 (7374): 525–528. doi:10.1038/Nature10617. PMID 22048311.

- ^ Fergal MacErlean (10 February 2012). "First Neanderthal cave paintings discovered in Spain". New Scientist. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Viegas, Jennifer (27 March 2013). "First Love Child of Human, Neanderthal Found". Discovery News. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "Neanderthals were not less intelligent than modern humans, scientists find". April 30, 2014. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "BBC News - New dates rewrite Neanderthal story". BBC News.

- ^ Dargie, Richard (2007). A History of Britain. London: Arcturus. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-572-03342-2. OCLC 124962416.

- ^ "Ancient tooth provides evidence of Neanderthal movement" (Press release). Durham University. 11 February 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ O'Neill, Dennis. "Evolution of Modern Humans: Neanderthals", Palomar College, June 10, 2011, accessed August 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c Jordan, P. (2001) Neanderthal: Neanderthal Man and the Story of Human Origins. The History Press ISBN 978-0-7509-2676-8.

- ^ Bilsborough, A, Rae, TC (2015) [REVISION OF] Hominoid cranial diversity and adaptation. In: Henke, W., Rothe, H. & Tattersall, I. (eds.) Handbook of Palaeoanthropology, New York: Springer

- ^ "Fieldwork - Jebel Irhoud". Max Planck Institute, Department of Human Evolution.

- ^ Arsuaga, J.L; Gracia, A; Martínez, I; Bermúdez de Castro, J.M; Rosas, A; Villaverde, V; Fumanal, M.P (1989). "The human remains from Cova Negra (Valencia, Spain) and their place in European Pleistocene human evolution". Journal of Human Evolution. 19: 55–92. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(89)90023-7.

- ^ Mallegni, F., Piperno, M., and Segre, A (1987). "Human remains of Homo sapiens neanderthalensis from the Pleistocene deposit of Sants Croce Cave, Bisceglie (Apulia), Italy". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 72 (4): 421–429. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330720402. PMID 3111268.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pavlov P, Roebroeks W, Svendsen JI (2004). "The Pleistocene colonization of northeastern Europe: a report on recent research". Journal of Human Evolution. 47 (1–2): 3–17. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.002. PMID 15288521.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wade, Nicholas (2 October 2007). "Fossil DNA Expands Neanderthal Range". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ Ravilious, Kate (1 October 2007). "Neandertals Ranged Much Farther East Than Thought". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ L’Homme de Neanderthal par Paul Dardé : L’Homme Primitif https://www.academia.edu/11187487/L_Homme_de_Neanderthal_par_Paul_Dard%C3%A9_L_Homme_Primitif

- ^ "Science & Nature—Wildfacts—Neanderthal". BBC. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Neanderthal". BBC. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ Froehle, Andrew W; Chruchill, Steven E (2009). "Energetic Competition Between Neandertals and Anatomically Modern Humans" (PDF). PaleoAnthropology: 96–116. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ Laleuza-Fox, Carles; Römpler, Holger; et al. (2007-10-25). "A Melanocortin 1 Receptor Allele Suggests Varying Pigmentation Among Neanderthals". Science. 318 (5855): 1453–5. Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1453L. doi:10.1126/science.1147417. PMID 17962522.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first2=(help); see also Rincon, Paul (25 October 2007). "Neanderthals 'were flame-haired'". BBC News. Retrieved 25 October 2007. - ^ a b "Neanderthal brains focused on vision and movement leaving less room for social networking". Science Daily. March 19, 2013.

- ^ SINC Servicio de Información y Noticias Científicas. "El cerebro neandertal era más asimétrico que el del 'Homo sapiens'".

- ^ "Neanderthal Brain Size at Birth Sheds Light on Human Evolution". National Geographic. 2008-09-09. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ^ Moskvitch, Katia (2010-09-24). "Neanderthals were able to 'develop their own tools'". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ^ Gray, Richard (December 18, 2011). "Neanderthals built homes with mammoth bones". Telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Evidence suggests Neanderthals took to boats before modern humans".

- ^ a b "Neanderthals were ancient mariners".

- ^ "Neanderthals beat modern humans to the seas by 50,000 years, say scientists".

- ^ "Ancient Mariners: Did Neanderthals Sail to Mediterranean?".

- ^ "Neanderthals May Have Sailed to Crete".

- ^ Bocherens, Hervé; Drucker, Dorothée G.; Billiou, Daniel; Patou-Mathis, Marylène; Vandermeersch, Bernard (2005). "Isotopic evidence for diet and subsistence pattern of the Saint-Césaire I Neanderthal: Review and use of a multi-source mixing model". Journal of Human Evolution. 49 (1): 71–87. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.03.003. PMID 15869783.

- ^ a b Ghosh, Pallab. "Neanderthals cooked and ate vegetables." BBC News. December 27, 2010.

- ^ Lichfield, John (September 30, 2006). "French dig up Neanderthal 'butcher's shop'". The New Zealand Herald.

- ^ a b Richards, Michael P.; Pettitt, Paul B.; Trinkaus, Erik; Smith, Fred H.; Paunović, Maja; Karavanić, Ivor (2000). "Neanderthal diet at Vindija and Neanderthal predation: The evidence from stable isotopes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (13): 7663–6. Bibcode:2000pnas...97.7663r. doi:10.1073/pnas.120178997. JSTOR 122870. PMC 16602. PMID 10852955.

- ^ Fiorenza, Luca; Benazzi, Stefano; Tausch, Jeremy; Kullmer, Ottmar; Bromage, Timothy G.; Schrenk, Friedemann (2011). Rosenberg, Karen (ed.). "Molar Macrowear Reveals Neanderthal Eco-Geographic Dietary Variation". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e14769. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014769. PMC 3060801. PMID 21445243.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Henry, A. G.; Brooks, A. S.; Piperno, D. R. (2010). "Microfossils in calculus demonstrate consumption of plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets (Shanidar III, Iraq; Spy I and II, Belgium)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (2): 486–491. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108..486H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016868108. PMC 3021051. PMID 21187393.

- ^ Webb, Jonathan (25 June 2014). "Oldest human faeces show Neanderthals ate vegetables". BBC News.

- ^ a b Shaw, Kate (July 29, 2011). "Sheer Numbers Gave Early Humans Edge Over Neanderthals". Wired.com.

- ^ a b Vergano, Dan (April 22, 2014). "Neanderthals Lived in Small, Isolated Populations, Gene Analysis Shows". National Geographic.

- ^ Zollikofer, Christoph; Marcia, Ponce; Leon, De; Vandermeersch, Bernard; Leveque, Francois (2002). "Evidence for Interpersonal Violence in the St. Césaire Neanderthal". PNAS. 99 (9): 6444–448. doi:10.1073/pnas.082111899. PMC 122968. PMID 11972028.

- ^ Brown, Cynthia Stokes. Big History. New York, NY: The New Press, 2008. Print.

- ^ Moulson, Geir; Associated Press (20 July 2006). "Neanderthal genome project launches". MSNBC. Retrieved 22 August 2006.

- ^ Lunine 2013, p. 251: "The Neanderthal genome is about the same size as the human genome, and is identical to ours to a level of 99.7% (this is comparing the ordering of the lettering in the nucleotide bases)."

- ^ Green RE, Krause J, Ptak SE; et al. (November 2006). "Analysis of one million base pairs of Neanderthal DNA". Nature. 444 (7117): 330–6. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..330G. doi:10.1038/nature05336. PMID 17108958.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wade, Nicholas (15 November 2006). "New Machine Sheds Light on DNA of Neanderthals". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ Pennisi, E. (May 2007). "Ancient DNA. No sex please, we're Neandertals". Science. 316 (5827): 967. doi:10.1126/science.316.5827.967a. PMID 17510332.

- ^ "Neanderthal bone gives DNA clues". CNN. Associated Press. 16 November 2006. Archived from the original on 18 November 2006. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ Than, Ker; LiveScience (15 November 2006). "Scientists decode Neanderthal genes". MSNBC. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ "Neanderthal Genome Sequencing Yields Surprising Results And Opens A New Door To Future Studies" (Press release). Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. 16 November 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ^ a b Hayes, Jacqui (15 November 2006). "DNA find deepens Neanderthal mystery". Cosmos. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ Green, Re; Malaspinas, As; Krause, J; Briggs, Aw; Johnson, Pl; Uhler, C; Meyer, M; Good, Jm; Maricic, T; Stenzel, U; Prüfer, K; Siebauer, M; Burbano, Ha; Ronan, M; Rothberg, Jm; Egholm, M; Rudan, P; Brajković, D; Kućan, Z; Gusić, I; Wikström, M; Laakkonen, L; Kelso, J; Slatkin, M; Pääbo, S (August 2008). "A complete Neandertal mitochondrial genome sequence determined by high-throughput sequencing". Cell. 134 (3): 416–26. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.021. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 2602844. PMID 18692465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evans PD, Mekel-Bobrov N, Vallender EJ, Hudson RR, Lahn BT (November 2006). "Evidence that the adaptive allele of the brain size gene microcephalin introgressed into Homo sapiens from an archaic Homo lineage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (48): 18178–83. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10318178E. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606966103. PMC 1635020. PMID 17090677.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Evans PD, Gilbert SL, Mekel-Bobrov N, Vallender EJ, Anderson JR, Vaez-Azizi LM, Tishkoff SA, Hudson RR, Lahn BT (September 2005). "Microcephalin, a gene regulating brain size, continues to evolve adaptively in humans". Science. 309 (5741): 1717–20. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.1717E. doi:10.1126/science.1113722. PMID 16151009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Elizabeth Pennisi (2009). "NEANDERTAL GENOMICS: Tales of a Prehistoric Human Genome". Science. 323 (5916): 866–871. doi:10.1126/science.323.5916.866. PMID 19213888.

- ^ Green RE, Briggs AW, Krause J, Prüfer K, Burbano HA, Siebauer M, Lachmann M, Pääbo S. (2009). "The Neandertal genome and ancient DNA authenticity". EMBO J. 28 (17): 2494–502. doi:10.1038/emboj.2009.222. PMC 2725275. PMID 19661919.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Neanderthals did not interbreed with humans, scientists find. Telegraph. Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ^ Neanderthals 'unlikely to have interbred with human ancestors' | Science. The Guardian. Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ^ Lowery, Robert K.; Uribe, Gabriel; Jimenez, Eric B.; Weiss, Mark A.; Herrera, Kristian J.; Regueiro, Maria; Herrera, Rene J. (Nov 2013). "Neanderthal and Denisova genetic affinities with contemporary humans: Introgression versus common ancestral polymorphisms". Gene. 530 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.005. PMID 23872234. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

- ^ a b Finlayson, C., Carrión, J.S. (April 2007). "Rapid ecological turnover and its impact on Neanderthal and other human populations". Trends in Ecology & Evolution (Personal Edition). 22 (4): 213–22. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2007.02.001. PMID 17300854.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "First genocide of human beings occurred 30,000 years ago". Pravda. 24 October 2007. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ Diamond, Jared M. (1992). The third chimpanzee: the evolution and future of the human animal. New York City: HarperCollins. p. 52. ISBN 0-06-098403-1. OCLC 60088352.

- ^ Currat, Mathias; Excoffier, Laurent (2004). "Modern Humans Did Not Admix with Neanderthals during Their Range Expansion into Europe". PLOS Biology. 2 (12): e421. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020421. PMC 532389. PMID 15562317.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "The Mysterious Downfall of the Neandertals", Scientific American, August 2009

- ^ Adler, Daniel S.; Bar-Oz, Guy; Belfer-Cohen, Anna; Bar-Yosef, Ofer (2006). "Ahead of the Game: Middle and Upper Palaeolithic Hunting Behaviors in the Southern Caucasus". Current Anthropology. 47 (1): 89–118. doi:10.1086/432455.

- ^ Froehle, Andrew W.; Churchill, Steven E. (2009). "Energetic Competition Between Neandertals and Anatomically Modern Humans" (PDF). PaleoAnthropology: 96–116.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (November 2, 2011). "Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought". New York Times. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ Wolff, H. "Result Filters." National Center for Biotechnology Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine, July 2010. Web. 22 Oct. 2014.

- ^ How hunting with wolves helped humans outsmart the Neanderthals, The Guardian, 28 February 2015

- ^ Stringer, Chris (2012). "Evolution: What makes a modern human". Nature. 485 (7396): 33–5. Bibcode:2012Natur.485...33S. doi:10.1038/485033a. PMID 22552077.

- ^ http://img.kb.dk/tidsskriftdk/pdf/gto/gto_0019-PDF/gto_0019_67206.pdf[full citation needed]

- ^ Dan Jones: The Neanderthal within., New Scientist 193.2007, H. 2593 (3 March), 28–32. Modern Humans, Neanderthals May Have Interbred; Humans and Neanderthals interbred

- ^ [3]; [http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/story/0,,1871842,00.html[full citation needed]

- ^ Not a lasting last for the Neandertals - John Hawks weblog, September 13, 2006 [full citation needed]

- ^ Soficaru, Andrei; Dobos, Adrian; Trinkaus, Erik (2006). "Early modern humans from the Pestera Muierii, Baia de Fier, Romania". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (46): 17196–201. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10317196S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608443103. JSTOR 30052409. PMC 1859909. PMID 17085588.

- ^ "Cousins of Neanderthals Left DNA in Africa, Scientists Report". The New York Times. July 26, 2012.

- ^ Yotova, V.; Lefebvre, J.-F.; Moreau, C.; Gbeha, E.; Hovhannesyan, K.; Bourgeois, S.; Bédarida, S.; Azevedo, L.; Amorim, A.; Sarkisian, T.; Avogbe, P. H.; Chabi, N.; Dicko, M. H.; Kou' Santa Amouzou, E. S.; Sanni, A.; Roberts-Thomson, J.; Boettcher, B.; Scott, R. J.; Labuda, D. (2011). "An X-Linked Haplotype of Neandertal Origin is Present Among All Non-African Populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (7): 1957–62. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr024. PMID 21266489.

- ^ "All Non-Africans Part Neanderthal, Genetics Confirm". DNews.

- ^ Neandertal ancestry "Iced" - John Hawks weblog, August 15, 2012 [full citation needed]

- ^ "Resurrecting Surviving Neandertal Lineages from Modern Human Genomes". Science. 2014-01-29. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Mitchell, Alanna (January 30, 2012). "DNA Turning Human Story Into a Tell-All". NYTimes. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ^ Lohse, Konrad; Frantz, Laurent A. F. (2013). "Maximum likelihood evidence for Neandertal admixture in Eurasian populations from three genomes". Populations and Evolution. 1307: 8263. arXiv:1307.8263. Bibcode:2013arXiv1307.8263L.

- ^ Jha, Alok (14 August 2012). "Study casts doubt on human-Neanderthal interbreeding theory". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Lowery, Robert K.; Uribe, Gabriel; Jimenez, Eric B.; Weiss, Mark A.; Herrera, Kristian J.; Regueiro, Maria; Herrera, Rene J. (2013). "Neanderthal and Denisova genetic affinities with contemporary humans: Introgression versus common ancestral polymorphisms". Gene. 530 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.005. PMID 23872234.

- ^ Hawks, John (2013). "Significance of Neandertal and Denisovan Genomes in Human Evolution". Annual Review of Anthropology. 42: 433–49. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155548.

- ^ Krings, Matthias; Stone, Anne; Schmitz, Ralf W; Krainitzki, Heike; Stoneking, Mark; Pääbo, Svante (1997). "Neandertal DNA Sequences and the Origin of Modern Humans". Cell. 90 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80310-4. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0025-0960-8. PMID 9230299.

- ^ Mason, Paul H.; Short, Roger V. (2011). "Neanderthal-human Hybrids". Hypothesis. 9: e1. doi:10.5779/hypothesis.v9i1.215.

- ^ Viegas, Jennifer (27 March 2013). "First Love Child of Human, Neanderthal Found". Discovery.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Condemi, Silvana; Mounier, Aurélien; Giunti, Paolo; Lari, Martina; Caramelli, David; Longo, Laura (2013). Frayer, David (ed.). "Possible Interbreeding in Late Italian Neanderthals? New Data from the Mezzena Jaw (Monti Lessini, Verona, Italy)". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e59781. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059781. PMC 3609795. PMID 23544098.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ The Neanderthal Dead, exploring mortuary variability in middle paleolithic eurasia. Paul B. Pettitt (2002)

- ^ "Homo neanderthalensis–The Neanderthals". Australian Museum. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ Bischoff, J; Shamp, Donald D.; Aramburu, Arantza; Arsuaga, Juan Luis; Carbonell, Eudald; Bermudez De Castro, J.M. (2003). "The Sima de los Huesos Hominids Date to Beyond U/Th Equilibrium (>350kyr) and Perhaps to 400–500kyr: New Radiometric Dates". Journal of Archaeological Science. 30 (3): 275–280. doi:10.1006/jasc.2002.0834.

- ^ Arsuaga JL, Martínez I, Gracia A, Lorenzo C (1997). "The Sima de los Huesos crania (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). A comparative study". Journal of Human Evolution. 33 (2–3): 219–81. doi:10.1006/jhev.1997.0133. PMID 9300343.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kreger, C. David. "Homo neanderthalensis". ArchaeologyInfo.com. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ Mcdermott, F; Grün, R; Stringer, Cb; Hawkesworth, Cj (May 1993). "Mass-spectrometric U-series dates for Israeli Neanderthal/early modern hominid sites". Nature. 363 (6426): 252–5. Bibcode:1993Natur.363..252M. doi:10.1038/363252a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 8387643.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rink, W. Jack, H.P. Schwarcz, H.K. Lee, J. Rees-Jones, R. Rabinovich & E. Hovers (August 2002). "Electron spin resonance (ESR) and thermal ionization mass spectrometric (TIMS) 230Th/234U dating of teeth in Middle Paleolithic layers at Amud Cave, Israel". Geoarchaeology. 16 (6): 701–717. doi:10.1002/gea.1017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Valladas, Hélène, N. Merciera, L. Frogeta, E. Hoversb, J.L. Joronc, W.H. Kimbeld & Y. Rak (March 1999). "TL Dates for the Neanderthal Site of the Amud Cave, Israel". Journal of Archaeological Science. 26 (3): 259–268. doi:10.1006/jasc.1998.0334.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Rincon, Paul (13 September 2006). "Neanderthals' 'last rock refuge'". BBC News. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ Conard, Nj; Grootes, Pm; Smith, Fh (July 2004). "Unexpectedly recent dates for human remains from Vogelherd". Nature. 430 (6996): 198–201. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..198C. doi:10.1038/nature02690. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15241412.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Higham T, Ramsey CB, Karavanić I, Smith FH, Trinkaus E (January 2006). "Revised direct radiocarbon dating of the Vindija G1 Upper Paleolithic Neandertals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (3): 553–7. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..553H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510005103. PMC 1334669. PMID 16407102.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hayes, Jacqui (2 November 2006). "Humans and Neanderthals interbred". Cosmos. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ Neanderthal image by Kupka, based on Boule, 1909, in Humanity's Journeys Dr. Kathryn Denning, 2005, retrieved 2012-03-17

- ^ Atelier Daynes, Neanderthal reconstructions, retrieved 2012-03-17

- ^ Replica of a Neanderthal child, The Ancient Edge Back European Neanderthals Overwhelmed by Sheer Numbers of Invading Homo Sapiens, Genevieve Maul, August 10th 2011, retrieved 2012-03-17

Journals

- Boë, Louis-Jean; Heim, Jean-Louis; Honda, Kiyoshi; Maeda, Shinji (2002). "The potential Neandertal vowel space was as large as that of modern humans". Journal of Phonetics. 30 (3): 465–84. doi:10.1006/jpho.2002.0170.

- Lieberman, Philip (October 2007). "Current views on Neanderthal speech capabilities: A reply to Boe et al. (2002)". Journal of Phonetics. 35 (4): 552–63. doi:10.1016/j.wocn.2005.07.002.

- Serre, David; Langaney, André; Chech, Mario; Teschler-Nicola, Maria; Paunovic, Maja; Mennecier, Philippe; Hofreiter, Michael; Possnert, Göran; Pääbo, Svante (2004). "No Evidence of Neandertal mtDNA Contribution to Early Modern Humans". PLOS Biology. 2 (3): e57. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020057. PMC 368159. PMID 15024415.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Wild, Eva M.; Teschler-Nicola, Maria; Kutschera, Walter; Steier, Peter; Trinkaus, Erik; Wanek, Wolfgang (2005). "Direct dating of Early Upper Palaeolithic human remains from Mladeč". Nature. 435 (7040): 332–5. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..332W. doi:10.1038/nature03585. PMID 15902255.

- Shaw, Kerry L. (2002). "Conflict between nuclear and mitochondrial DNA phylogenies of a recent species radiation: What mtDNA reveals and conceals about modes of speciation in Hawaiian crickets". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (25): 16122–7. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916122S. doi:10.1073/pnas.242585899. JSTOR 3073918. PMC 138575. PMID 12451181.

- Zilhão, João; Davis, Simon J. M.; Duarte, Cidália; Soares, António M. M.; Steier, Peter; Wild, Eva (2010). Hawks, John (ed.). "Pego do Diabo (Loures, Portugal): Dating the Emergence of Anatomical Modernity in Westernmost Eurasia". PLOS ONE. 5 (1): e8880. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008880. PMC 2811729. PMID 20111705.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lay-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lay-source=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

Bibliography

- Derev'anko, Anatoliy P.; Powers, William Roger; Shimkin, Demitri Boris (1998). The Paleolithic of Siberia: new discoveries and interpretations. Novosibirsk: Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography. ISBN 978-0-252-02052-0. OCLC 36461622.

- Lunine, Jonathan I. (2013). Earth: Evolution of a Habitable World. Cambridge University Press. 327. ISBN 978-0-521-85001-8.

External links edit

- Kreger, C. David (30 June 2000). "Homo neanderthalensis". ArchaeologyInfo.com. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- O'Neil, Dennis (12 May 2009). "Evolution of Modern Humans: Neandertals". Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- "Homo neanderthalensis". The Smithsonian Institution.

- "Neanderthal DNA". International Society of Genetic Genealogy.: Includes Neanderthal mtDNA sequences