| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

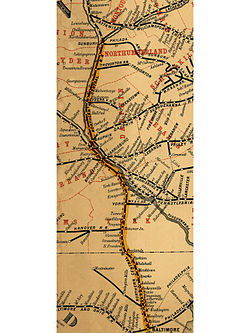

1863 map showing crossing of the Susquehanna River on the Marysville Bridge. Traffic was later routed over the Rockville Bridge. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Baltimore |

| Reporting mark | NCRY |

| Locale | Pennsylvania and Maryland |

| Dates of operation | 1858–1976 |

| Predecessor | ... Railroad, .... Line Rail Road, .... Railroad |

| Successor | ConRail |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 380 miles (610 km) (including leased lines)[1] |

The York, Hanover and Frederick Railway was a Class I Railroad connecting Frederick, Maryland with York, Pennsylvania. Completed in 18..., the line came under the control of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) in 18..., when the PRR acquired a controlling interest in the Northern Central's stock to compete with the rival Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O). Thereafter, the Northern Central operated as a subsidiary of the PRR until much of its Maryland trackage was washed out by Hurricane Agnes in 1972.

Early history

editThe Baltimore and Susquehanna Railroad Company was chartered by an act of the legislature of Maryland on February 13, 1828, with authority to construct a railroad from Baltimore to the Susquehanna River. To reach the Susquehanna at any commercially useful point, the new line would have to cross the state line into York County, Pennsylvania. However, the Pennsylvania legislature did not look favorably on the prospect of the trade of its southern counties being tapped for the benefit of Baltimore, instead of Philadelphia, and would not grant a charter for a connecting railroad. Construction had begun in 1829, and reached as far north as the York Road at Cockeysville by 1831. At that time, the Baltimore & Susquehanna obtained an amendment to its charter from the Maryland legislature which allowed it to be built via Westminster into the headwaters of Monocacy Creek, intending to reach Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. New construction began at Hollins and ran west through the Green Spring Valley. The line reached the Reistertown Road at Owings Mills on June 13, 1832. However, despite fierce opposition from Philadelphia interests, the Pennsylvania legislature finally chartered the York and Maryland Line Rail Road on March 14, 1832, authorizing it to connect the Baltimore & Susquehanna, at the state line, with York, Pennsylvania, a commercial center on Codorus Creek.

The directors of the Baltimore & Susquehanna did not immediately give up their planned route via Westminster, the terms of the new charter being somewhat onerous. The Adams County Railroad was chartered on April 6, 1832, in Pennsylvania, to run from Gettysburg to the Maryland state line, but was never constructed, nor was the line to Westminster (later the Green Spring Branch) extended. A further amendment to the York & Maryland Line's charter in 1837 allowed it the unlimited use of the Wrightsville, York and Gettysburg Railroad, which it had aided financially. The Baltimore & Susquehanna, and York & Maryland Line had completed the line from Baltimore to York by 1838. This line included the Howard Tunnel, the earliest railroad tunnel in the U.S. still in use today.

In 1832 the railroad purchased its first locomotive, the Herald, which was run along the route from Baltimore to Owings Mills.[2]: 168 This purchase was a major undertaking, for it was built in England and transported by ship The America's. Also, because the age of railroading was new to America, an engineer was sent with the locomotive to ensure that he could teach others the finer art of locomotive engineering. John Lawson, (b. Makerfield, November 27, 1810) went on to own, captain and be first engineer to the Cherokee steamboat, which helped with the Confederate Army effort during the American Civil War.

Also in 1832, the railroad built Bolton Station, with an adjacent roundhouse and shops, at Bolton and Howard Streets in Baltimore.[3]: 88

In April 1840, the Wrightsville, York & Gettysburg had been completed between York and Wrightsville, on the Susquehanna. There a connection was made to the Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge, allowing trains to cross the river and reach the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad and later, the Pennsylvania Railroad just prior to the Civil War. The railroad provided an alternative method of shipping cargo from central Pennsylvania to the Maryland seaports versus the Tide Water and Susquehanna Canal. However, the cost of expansion and inconsistent tariff policies plagued the Baltimore & Susquehanna and limited further growth.

The York and Cumberland Railroad Company was chartered on April 21, 1846 to connect the York & Maryland Line with the Cumberland Valley Railroad somewhere north of Mechanicsburg. It was opened on February 10, 1851, running north from York to the Susquehanna and then following the river to Lemoyne, across the river from Harrisburg. It was briefly operated by the Cumberland Valley, but the Baltimore & Susquehanna took over operations on June 7. Work also began on the Hanover Branch Railroad, a line connecting Hanover with the York & Maryland Line at Hanover Junction.

The Baltimore & Susquehanna opened Calvert Station in Baltimore in 1850.[4]: 279

On April 14, 1851, the Susquehanna Railroad was chartered to build north from the York & Cumberland or the Pennsylvania Railroad up the Susquehanna through Halifax, Millersburg and Sunbury, where it would fork into two branches reaching Williamsport and Wilkes-Barre. It was an ambitious enterprise, badly in need of capital, and as yet unorganized. The charter was amended on April 24, 1852, to allow the York & Cumberland and Wrightsville, York & Gettysburg to subscribe or loan up to $500,000 to the company, and to permit the counties and boroughs along the way to contribute funds. The Maryland legislature authorized the City of Baltimore to contribute the same amount on May 14. The Susquehanna RR finally elected officers on June 10, and was soon embroiled in a dispute with the Sunbury and Erie Railroad over right-of-way.

Meanwhile, on May 27, the Baltimore, Carroll and Frederick Railroad (renamed the Western Maryland Railroad in 1853) was incorporated to build from the end of the line at Owings Mills towards Hagerstown. On July 4, a serious accident occurred on the Baltimore & Susquehanna when a special picnic excursion collided with a York local, killing thirty-one persons. The Hanover Branch Railroad was opened to Hanover on October 22 and operated by the Baltimore & Susquehanna. On May 10, 1853, the Baltimore & Susquehanna's charter was amended to permit it to build two branches to the Patapsco River (the Canton Extension), but this was stymied by legal problems and difficulties in tunneling.

On the northward extension, the Susquehanna RR let contracts for the line from Lemoyne to Sunbury in November 1852, and construction began on February 22, 1853. A financial crisis beginning in the fall of 1853 proved a severe embarrassment to the Baltimore & Susquehanna and associated railroads, and on March 10, 1854, the Maryland legislature authorized the Baltimore & Susquehanna, York & Maryland Line, York & Cumberland, and Susquehanna Railroads to merge, writing off its investment in the lines in exchange for a mortgage on the new railroad. Construction halted on the Susquehanna RR. The Pennsylvania legislature authorized the merger on May 3, and articles of consolidation were signed on December 4 (filed December 16, 1854), forming the Northern Central Railway Company.[1]

On April 1, 1855, the Northern Central stopped operating the Hanover Branch RR, which began independent operation. On December 20, 1855, construction resumed on the northward extension, and by December 28, 1856, the line had bridged the Susquehanna at Dauphin and reached Millersburg, connecting with the Dauphin and Susquehanna Railroad and the Lykens Valley Railroad, respectively. These were lateral lines tapping coal mines east of the Susquehanna, and the extension afforded them a direct outlet by rail rather than by canal boat. In 1857, it reached Herndon and the Trevorton Coal and Railroad Company, another mining line. On June 28, 1858, the line was opened to Sunbury, where it connected with the Shamokin Valley and Pottsville Railroad, to Shamokin, and the Sunbury and Erie Railroad, to Williamsport.

In 1861, the PRR acquired a controlling interest in the Northern Central's stock to compete with the rival B&O. Thereafter, the Northern Central operated as a subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad until the latter's demise in the late 20th century.[3]: 22

Consolidation and Civil War

editDuring the Civil War, the Pennsylvania Railroad-controlled Northern Central served as a major transportation route for supplies, food, clothing, and materiel, as well as troops heading to the South from Camp Curtin and other Northern military training stations. During the 1863 Gettysburg Campaign, Confederate Major General Jubal A. Early raided the NCR during his occupation of York, burning some rolling stock and a few machine shops in the rail yard. To impair traffic between Baltimore and Harrisburg, his cavalry destroyed a large number of York County bridges originally constructed by the B&S. They were quickly rebuilt by Herman Haupt and the U.S. Army Military Railroad in conjunction with the Northern Central Railway. Traffic resumed shortly thereafter, and thousands of wounded soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg, including Union Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles, were evacuated via the Northern Central to hospitals in Harrisburg, Baltimore, York, and elsewhere.

The Northern Central was attacked again on July 10, 1864, when a 130-man Confederate cavalry detachment attacked the line near Cockeysville, under orders from Gen. Bradley T. Johnson. After cutting telegraph wires along Harford Road, they encamped at Towson overnight. The next day, the Confederate cavalry skirmished with a smaller force of Union cavalry along York Road as far south as Govens, before heading west to rejoin Gen. Johnson's main force.[5]: 127–129

Abraham Lincoln traveled on the Northern Central on his way to deliver the Gettysburg Address in November 1863, changing trains in Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania. After Lincoln's assassination, his body was transported via the same rails on the funeral train's journey from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois. The nine-car train departed Washington on April 21, 1865, arriving at Baltimore's Camden Station at 10 a.m. on the B&O Railroad.[5]: 152 After public viewing of the President's remains, the train departed Baltimore on the Northern Central at 3 p.m. and arrived at Harrisburg at 8:20 p.m., with a brief stop at York.[6][7]

In 1873 the NCRY opened its Charles Street Station, and the Union Railroad of Baltimore opened a new line connecting to the station. This 9.62 mile (15.48 km) railroad gave the NCRY access to the Canton area, where it established a shipping terminal on the Inner Harbor. The line also completed a crucial link in central Baltimore between the NCRY, the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad and the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad. In February 1882 the Northern Central acquired the Union Railroad.[8] The Union Railroad link enabled the PRR to operate through trains between Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C., and the route generated serious competition for the B&O. Today this PRR system is part of the Northeast Corridor.

In 1898, the NCRY built the Millersburg Passenger Rail Station.[9]

Twentieth century

editThe Pennsylvania Railroad's Northern Central line was double-tracked and equipped with block signals between Baltimore and Harrisburg by World War I. The line carried heavy passenger and freight traffic until the 1950s. On-line freight included flour, paper, milk, farm products, coal, and less-than-carload shipments between such settlements as White Hall, Parkton, Bentley Springs, Lutherville, and the city of Baltimore. Local commuter service, referred to as the "Parkton local," operated over the 28 miles (45 km) between Calvert Station in Baltimore and Parkton, Maryland. Long distance passenger trains equipped with sleepers and dining cars were also operated by the PRR over the line from Baltimore Penn Station to Buffalo, Toronto, Chicago, Illinois, and St. Louis, Missouri, with through-sleeping car service as far as Houston, Texas (see 1955 timetable, below). Much of the "Pennsy's" through freight service to points west was routed via its electrified Port Road Branch along the Susquehanna River to Enola Yard in Harrisburg, however, instead of the Northern Central line.

With the decline in rail passenger and freight service in the 1950s, accelerated by completion of the Baltimore-Harrisburg Expressway (I-83), the "Parkton locals" were dropped in 1959 and the line was reduced from double-track to single-track. Some long-distance trains, such as the General to Chicago and the Buffalo Day Express, continued to operate until the late 1960s. In 1972, when Hurricane Agnes caused bridge damage and washouts along the line, it ceased operations completely. One of the oldest rail lines in the country, it had run for a total of 134 years.

Penn Central and aftermath

editIn 1968 the PRR merged with the New York Central railroad, to form the Penn Central (PC).

After sustaining damage along the main line due to Hurricane Agnes, the PC petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to abandon the railroad south of York. The section of the line between York and New Freedom was acquired by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation in June 1973.[10]

A series of events including inflation, poor management, abnormally harsh weather conditions and the withdrawal of a government-guaranteed 200-million-dollar operating loan forced the Penn Central to file for bankruptcy protection in 1970.[11]: 233–234 PRR operated under court supervision until 1976, when its lines were tranferred to a new government corporation, Conrail.[12]: 4–5 (See Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act.)

The Maryland Department of Natural Resources converted the corridor north of Cockeysville into a trail which opened to the public in 1984. It is known in Maryland as the Torrey C. Brown Rail Trail. The trail continues into Pennsylvania, where it becomes the York County Heritage (YCH) trail.[13] The line south of Cockeysville was rebuilt in the late 1980s and is now part of the double-tracked Baltimore Light Rail system.

In York County, the Bridge 182+42, Bridge 5+92, Bridge 634, South Road Bridge, Howard Tunnel, and New Freedom Railroad Station are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[14]

The NCRY operated as a dinner train in the mid 1990s to the early 2000s. Starting June 1, 2013, the NCRY will resume operations between New Freedom and Hanover Junction, operating a Kloke locomotive works replica of a Civil War-era 4-4-0 American type steam locomotive.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Henry Varnum Poor (1900). Poor's Manual of the Railroads of the United States. Vol. 33. New York: H.V. & H.W. Poor. p. 703.

- ^ White, Jr., John H. (1980). A history of the American locomotive: its development, 1830-1880. Mineola, NY: Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-23818-0.

- ^ a b Harwood, Jr., Herbert H. (1990). Royal Blue Line. Sykesville, MD: Greenberg Publishing. ISBN 0-89778-155-4.

- ^ Wilson, William Bender (1895). History of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company with Plan of Organization, Portraits of Officials and Biographical Sketches. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Henry T. Coates & Company. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ a b Toomey, Daniel Carroll (1983). The Civil War in Maryland. Baltimore, MD: Toomey Press. ISBN 0-9612670-0-3.

- ^ Goodrich, Thomas (2005). The Darkest Dawn. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University. p. 195. ISBN 0-253-32599-4.

- ^ Hansen, Peter A. (February 2009). "The funeral train, 1865". Trains. 69 (2). Kalmbach: 34–37. ISSN 0041-0934.

- ^ Hall, Clayton (1912). Baltimore: Its History and Its People. Vol. 1. Lewis Historical Pub. Co. pp. 487–8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|middle=ignored (help) - ^ "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Note: This includes Elizabeth Roman (July 2001). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Millersburg Passenger Rail Station" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ Northern Central Railcar Association, New Freedom, PA. "Northern Central History" Accessed 2012-05-26.

- ^ Stover, John F. (1997). American Railroads (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77658-3.

- ^ United States Railway Association (USRA), Washington, DC. "The Conveyance Process: A Supplement to the Final Report of the United States Railway Association." December 1986.

- ^ "Blazing a Trail". Chesapeake Life Magazine. Alter Communications. 2002-07. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

Passenger service along the NCR had been curtailed in 1959, but freight service continued until 1972, when Hurricane Agnes swept through the area, destroying much of the track, as well as bridges and culverts.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Gunnarsson, Robert L. (1991). The Story of the Northern Central Railway. Sykesville, MD: Greenberg Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-89778-157-2.

External links

edit- NCRY Annual reports, 1865-1866 (11th-12th), 1869-1910 (15th-56th)

- PRR Corporate History

- PRR Chronology, Chris Baer

Category:Defunct Maryland railroads

Category:Defunct Pennsylvania railroads

Category:Defunct New York (state) railroads

Category:Predecessors of the Pennsylvania Railroad

Category:Pennsylvania in the American Civil War

Category:History of Maryland

Category:History of Pennsylvania

Category:Former Class I railroads in the United States

Category:Railway companies established in 1854

Category:Railway companies disestablished in 1976

Category:Transportation in York County, Pennsylvania