| Dengue fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Dengue, breakbone fever[1][2] |

| |

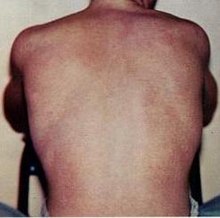

| The typical rash seen in dengue fever | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, rash[1][2] |

| Complications | Bleeding, low levels of blood platelets, dangerously low blood pressure[2] |

| Usual onset | 3–14 days after exposure[2] |

| Duration | 2–7 days[1] |

| Causes | Dengue virus by Aedes mosquitos[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Detecting antibodies to the virus or its RNA[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Malaria, yellow fever, viral hepatitis, leptospirosis[3] |

| Prevention | Dengue fever vaccine, decreasing mosquito exposure[1][4] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, intravenous fluids, blood transfusions[2] |

| Frequency | 390 million per year[5] |

| Deaths | ~40,000[6] |

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the dengue virus.[1] Symptoms typically begin three to fourteen days after infection.[2] These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin rash.[1][2] Recovery generally takes two to seven days.[1] In a small proportion of cases, the disease develops into severe dengue, also known as dengue hemorrhagic fever, resulting in bleeding, low levels of blood platelets and blood plasma leakage, or into dengue shock syndrome, where dangerously low blood pressure occurs.[1][2]

Dengue is spread by several species of female mosquitoes of the Aedes type, principally A. aegypti.[1][2] The virus has five types;[7][8] infection with one type usually gives lifelong immunity to that type, but only short-term immunity to the others.[1] Subsequent infection with a different type increases the risk of severe complications.[1] A number of tests are available to confirm the diagnosis including detecting antibodies to the virus or its RNA.[2]

A vaccine for dengue fever has been approved and is commercially available in a number of countries.[4][9] As of 2018, the vaccine is only recommended in individuals who have been previously infected, or in populations with a high rate of prior infection by age nine.[10][5] Other methods of prevention include reducing mosquito habitat and limiting exposure to bites.[1] This may be done by getting rid of or covering standing water and wearing clothing that covers much of the body.[1] Treatment of acute dengue is supportive and includes giving fluid either by mouth or intravenously for mild or moderate disease.[2] For more severe cases, blood transfusion may be required.[2] About half a million people require hospital admission every year.[1] Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is recommended instead of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for fever reduction and pain relief in dengue due to an increased risk of bleeding from NSAID use.[2][11][12]

Dengue has become a global problem since the Second World War and is common in more than 120 countries, mainly in Southeast Asia, South Asia and South America.[5][13][14] About 390 million people are infected a year and approximately 40,000 die.[5][6] In 2019 a significant increase in the number of cases was seen.[15] The earliest descriptions of an outbreak date from 1779.[14] Its viral cause and spread were understood by the early 20th century.[16] Apart from eliminating the mosquitos, work is ongoing for medication targeted directly at the virus.[17] It is classified as a neglected tropical disease.[18]

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Dengue and severe dengue Fact sheet N°117". WHO. May 2015. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kularatne SA (September 2015). "Dengue fever". BMJ. 351: h4661. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4661. PMID 26374064.

- ^ Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics: The field of pediatrics. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2016. p. 1631. ISBN 9781455775668. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b East S (6 April 2016). "World's first dengue fever vaccine launched in the Philippines". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Dengue and severe dengue". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017". Lancet. 392 (10159): 1736–88. November 2018. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. PMC 6227606. PMID 30496103.

- ^ Normile D (October 2013). "Tropical medicine. Surprising new dengue virus throws a spanner in disease control efforts". Science. 342 (6157): 415. doi:10.1126/science.342.6157.415. PMID 24159024.

- ^ Mustafa MS, Rasotgi V, Jain S, Gupta V (January 2015). "Discovery of fifth serotype of dengue virus (DENV-5): A new public health dilemma in dengue control". Medical Journal, Armed Forces India. 71 (1): 67–70. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2014.09.011. PMC 4297835. PMID 25609867.

- ^ "First FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of dengue disease in endemic regions". FDA (Press release). 1 May 2019. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ "Dengue vaccine: WHO position paper – September 2018" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 36 (93): 457–76. 7 September 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ "Dengue". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 March 2016. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

Use acetaminophen. Do not take pain relievers that contain aspirin and ibuprofen (Advil), it may lead to a greater tendency to bleed.

- ^ WHO (2009), pp. 32–37.

- ^ Ranjit S, Kissoon N (January 2011). "Dengue hemorrhagic fever and shock syndromes". Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 12 (1): 90–100. doi:10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e911a7. PMID 20639791.

- ^ a b Gubler DJ (July 1998). "Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 11 (3): 480–96. doi:10.1128/cmr.11.3.480. PMC 88892. PMID 9665979.

- ^ "Dengue and severe dengue". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Henchal EA, Putnak JR (October 1990). "The dengue viruses". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 3 (4): 376–96. doi:10.1128/CMR.3.4.376. PMC 358169. PMID 2224837. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- ^ Noble CG, Chen YL, Dong H, Gu F, Lim SP, Schul W, Wang QY, Shi PY (March 2010). "Strategies for development of Dengue virus inhibitors". Antiviral Research. 85 (3): 450–62. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.12.011. PMID 20060421.

- ^ "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.