Kingdom of Mauretania | |

|---|---|

| c. 3rd century BC–40 AD | |

| |

| Capital | Volubilis? Caesarea (from 25 BC) |

| Common languages | Berber Punic (elite, coinage) Greek (science) Latin (after 46 BC) |

| Religion | Traditional Berber religion Hellenistic religion |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Historical era | Classical antiquity |

• Foundation | c. 3rd century BC |

• Interregnum | 33 BC–25 BC |

• Reestablished as Roman client kingdom | 25 BC |

• Abolished by Emperor Caligula | 40 AD |

| Today part of | Morocco Algeria |

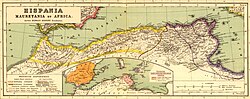

The Kingdom of Mauretania was an ancient Berber polity in what is now northern Morocco and Algeria that existed from around the 3rd century BC to its annexation by the Roman Empire in 40 AD.

Most of what is known about Mauretania's history revolves around its interactions with Rome and Numidia. A Mauretanian king, Baga, was first mentioned in 206 BC, when he allied with the Numidian king Massinissa. A century later king Bocchus I intervened in the Jugurthine War and expanded the kingdom as far east as Saldae. During the reigns of Bocchus II and Bogud it was briefly seperated into two parts before Bocchus II managed to reunify the kingdom and even annexed territories as far east as the Rhumel River, but his death in 33 BC left it practically defunct. Emperor Augustus restored the kingdom in 25 BC and installed Juba II and Cleopatra Selene as vassal rulers seated in Caesarea. Mauretania was finally annexed by Emperor Caligula in 40 AD and turned into the provinces of Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis.

It originated as a confederation led by the Mauri people, who due to their dominant position lend their name to the polity, but which also encompassed other tribal groups. The minting of coins only began in the second half of the 2nd century BC. Its society was divided in sedentary farmers and nomadic pastoralists. Most of the population encompassed Berber-speakers, which was written in an alphabet called Libyco-Berber, but the elite also used Punic. Juba II, who was highly educated and Romanized, was a proficient author employing Greek.

Geography

editThe ancients applied the term "Mauretania" to a vast and loosely defined region in northern Africa that originally stretched from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to Numidia in the east. In the late 2nd century BC, just before the eastward expansion of the kingdom, the border between Mauretania and Numidia was said to be the Muluccha river, likely corresponding to either the Moulouya River or the Wadi Kiss slightly further east.[1] The region is dominated by the Rif Mountains, which practically divided Mauretania in a western and an eastern part and the Atlas Mountains, which provided a natural southern boundary separating Mauretania from the Sahara. The mountainscape is interrupted by arid plains and, especially in western Mauretania, fertile rivers like the Sebou.[2]

History

editOrigins (before 2nd century BC)

editPlaceholder

From Bocchus I to the interregnum (late 2nd century BC–25 BC)

editWhat happened to Bocchus I after 91 BC remains unknown, although he might have ruled as late as 81 BC.[3]

Roman client kingdom (25 BC–40 AD)

editPlaceholder

Languages

editThe Mauretanians and Numidians spoke a Berber language that may have been related to Kabyle, which is still spoken in Kabylia in northeastern Algeria.[4] This language was written in the Libyco-Berber alphabet, which originated in the 3rd[5] or 2nd[6] century BC. There were two variants of the alphabet: an eastern one used east of Kabylia with 24 letters and a western one with 37 letters used as far west as the Canary Islands.[7][a] The inscriptons are usually very short[9] and correspond to epitaphs engraved on stone, although some inscriptions were also carved into pottery.[10] A notable example is a carefully crafted stele found near a tumulus in Sidi Slimane, likely from the 2nd century BC.[11]

Contrary to Numidia[12] there is only limited evidence for Carthaginian influence in Mauretania, including the usage of Punic. It was to some degree used by the elite:[13] a few Neo-Punic (the form of Punic written after the fall of Carthage) inscriptions dating to the late 2nd–1st century BC were found at Volubilis, mentioning individuals bearing the Punic title suffet,[14] meaning as much as "magistrate" or "prince".[15]

After 46 BC Latin quickly grew to become North Africa's Lingua Franca.[16] Around that time Latin began to be featured on the coins of Bogud, which only used Latin, and Bocchus II, which used Latin and Punic.[17] After the fall of Mauretania Latin replaced Berber throughout most of the northern Maghreb, reducing it to a few isolated pockets. This state persisted until a mass migration of Berber-speakers from the Sahara in the 5th century,[18] although African Romance remained dominant along the Mediterranean coast line until the arrival of the Arabs in the late 7th century.[19]

Numismatics

editCoins were introduced to Mauretania around the turn of the 3rd century BC, with the Numidian issues produced by Syphax and Massinissa. Numidian issues were highly popular and remained in circulation even after the Roman annexation. Carthaginian and Iberian coins also found their way into the country.[20] Under Bocchus I Mauretania finally began to mint its own coins,[21] although there is some evidence that coins were struck as early as the mid-2nd century BC.[20] Several Mauretanian towns minted their own bronze coins with Neo-Punic inscriptions, among them Lixus, Tingi and Rusadir. The iconography is repetitive, usually depicting a bare head on the obverse and wheat and grapes on the reverse.[22] After the annexation of western Numidia in 105 BC Mauretania also acquired a royal mint in Siga.[23] Siga produced a limited[24] number of coins bearing the Neo-Punic inscription bqs ("Bocchus"), who is likely to be identified with Bocchus I rather than Bocchus II.[25]

After Bocchus I there was a hiatus until the issues produced by Bogud and Bocchus II,[26] still very few in number[27] and hence still serving prestigious purposes.[28] While the coins of Bocchus II remained relatively orthodox[29] the silver issues produced under Bogud already show strong Roman influences.[17]

- Gallery

-

The stone circle of Msoura

-

Drawing of the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania by James Bruce, 1769

-

Remains of a statue of Thutmosis III found in Cherchel, likely brought from Egypt by Cleopatra Selene

-

Silver dish from the Boscoreale Treasure likely depicting Cleopatra Selene

-

Theatre of Caesarea built during the reign of Juba II

Notes

editCitations

edit- ^ Roller 2003, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Roller 2003, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Roller 2003, p. 51.

- ^ Fentress 2019, p. 508.

- ^ Blench 2019, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Callegarin & El Khayari 2016, p. 94.

- ^ Blench 2019, pp. 445–446.

- ^ Pichler 2007, pp. 64–68.

- ^ Blench 2019, p. 445.

- ^ Callegarin & El Khayari 2016, p. 92.

- ^ Callegarin & El Khayari 2016, pp. 85–90.

- ^ Bridoux 2014, p. 182.

- ^ Papi 2014, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Papi 2014, p. 216.

- ^ Papi 2014, p. 213.

- ^ Wilson 2012, pp. 268–269.

- ^ a b Alexandropolous 2007, pp. 206–208.

- ^ Fentress 2019, pp. 511–515.

- ^ Wright 2012, p. 42.

- ^ a b Callegarin 2011, p. 46.

- ^ Alexandropolous 2007, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Alexandropolous 2007, pp. 196–200.

- ^ Alexandropolous 2007, p. 194.

- ^ Alexandropolous 2007, p. 201.

- ^ Martínez Chico & Callegarin 2018, pp. 266–268.

- ^ Alexandropolous 2007, p. 195.

- ^ Alexandropolous 2007, p. 205.

- ^ Callegarin 2011, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Alexandropolous 2007, pp. 208–210.

Literature

edit- Alexandropolous, Jacques (2007). Les monnaies de l’Afrique antique. 400 av. J.-C. - 40 ap. J.-C. Presses universitaires du Midi.

- Blench, Roger (2019). "The Linguistic Prehistory of the Sahara". Burials, Migration and Identity in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Cambridge University. pp. 431–463.

- Bridoux, Virginie (2014). "Numidia and the Punic World". The Punic Mediterranean. Identities and Identification from Phoenician Settlement to Roman Rule. Cambridge University. pp. 180–201.

- Callegarin, Laurent; El Khayari, Abdelaziz (2016). "Le faciès culturel de la période maurétannie". Rirha. Site antique et médiéval du Maroc. Vol. II. Casa de Velázquez. pp. 85–116.

- Callegarin, Laurent (2011). "Coinages with Punic and neo-Punic legends of Western Mauretania. Attribution, chronology and currency circulation". Money, Trade and Trade Routes in Pre-Islamic North Africa. British Museum. pp. 42–48.

- Fentress, Elizabeth (2019). "The Archaeological and Genetic Correlates of Amazigh Linguistics". Burials, Migration and Identity in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Cambridge University. pp. 495–424.

- Martínez Chico, David; Callegarin, Laurent (2018), "La emisión númida de siga (ss. II-I A.C.) con jinete lanceando", SAGUNTUM. Papeles del Laboratorio de Arqueología de Valencia, 50, Universitat de València: 265–268, ISSN 0210-3729

- Papi, Emanuele (2014). "Punic Mauretania?". In Josephine Crawley Quinn, Nicholas C. Vella (ed.). The Punic Mediterranean. Identities and Identification from Phoenician Settlement to Roman Rule. Cambridge University. pp. 202–218. ISBN 110705527X.

- Pichler, Werner (2007). Origin and Development of the Libyco-Berber Script. Rüdiger Köppe.

- Roller, Duane W. (2003). The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene: Royal Scholarship on Rome's African Frontier. Routledge Classical Monographs. ISBN 0415305969.

- Wilson, Andrew (2012). "Neo-Punic and Latin inscriptions in Roman North Africa". Multilingualism in the Graeco-Roman Worlds. Cambridge University. pp. 265–316.

- Wright, Roger (2012). "Late and Vulgar Latin in Muslim Spain. The African connection". Actes du IXe colloque international sur le latin vulgaire et tardif, Lyon 2-6 septembre 2009. MOM Editions. pp. 35–54.

https://www.academia.edu/42953114/NEAR_EASTERN_COLONIES_AND_CULTURAL_INFLUENCES_FROM_MOROCCO_TO_ALGERIA_BEFORE_THE_CARTHAGINIAN_EXPANSION_A_SURVEY_OF_THE_ARCHAEOLOGICAL_EVIDENCE Revisiting First Millennium BC Graves in North-West Morocco https://journals.openedition.org/encyclopedieberbere/521

Further reading

edit- Ait Amara, Ouiza (2013). Numides et Maures Au Combat – États et armées en Afrique du Nord jusqu’à l’époque de Juba Ier. Sandhi.

- Aranegui, Carmen; Mar, Ricardo (2009). "Lixus (Morocco): from a Mauretanian sanctuary to an Augustan palace" (PDF). Papers of the British School at Rome. 77: 29–64.

- Aranegui, Carmen; Vives-Ferrándiz, Jaime. Romanization in the Far West: Local Practices in Western Mauritania (2nd c. BCE – 2nd c. CE) (PDF).

- Cravioto, Enrique Gozalbes (2010). "Los orígenes del Reino de Mauretania (Marruecos)" (PDF). POLIS. Revista de ideas y formas políticas de la Antigüedad Clásica. 22.

- Draycott, Jane (2024). Cleopatra's Daughter. From Roman Prisoner to African Queen.

- Levêque, Pierre (1999). "Couverture fascicule Avant et après les Princes. L'Afrique mineure de l'Age du fer". Les princes de la protohistoire et l’émergence de l’État. Actes de la table ronde internationale organisée par le Centre Jean Bérard et l'Ecole française de Rome Naples, 27-29 octobre 1994. pp. 153–164.

- Mugnai, N. (2018). Architectural Decoration and Urban History in Mauretania Tingitana. Quasar.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23800236?read-now=1&seq=16#page_scan_tab_contents https://www.persee.fr/doc/ktema_0221-5896_1996_num_21_1_2167

- Speidel, Michael P. (1993). "Mauri equites. The tactics on light cavalry in Mauretania". Antiquités africaines.

Kingdom of Tylis | |

|---|---|

| c. 278 BC–c. 212 BC | |

| Capital | Tylis |

| Common languages | Celtic (ruling elite) Thracian (common) |

| Religion | Celtic polytheism, Thracian polytheism |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Historical era | Classical antiquity |

• Foundation | c. 278 BC |

• Disestablished | c. 212 BC |

| Today part of | Bulgaria Turkey |

The kingdom of Tylis was an ancient Celtic kingdom in what is now Bulgaria and European Turkey. It was established shortly after the failed Celtic invasion of Greece in 279 BC, when chief Comontorius led survivors of the campaign into eastern Thrace and founded a new town named Tylis, henceforth the capital. Little is known about the history of the kingdom, although it seemed to have thrived on extorting tribute from its neighbours. It was finally destroyed during the rule of king Cavarus, who was deposed by rebellious Thracians in around 212 BC.

History

editEarly history

editInvasion of Greece

editThe Diodochos Lysimachus, who had ruled an empire stretching from Thessaly and Macedon into Asia Minor,[1] was killed in the Battle of Corupedium in 281.[2] Likely having checked previous Celtic incursions beforehand, it was his demise that allowed the Celts to push southwards.[3]

In 279 the Celts invaded the kingdom of Macedon. By that point most of Macedon was ruled by king Ptolemy Ceraunus, an usurper who had asserted his rule over his rival Antigonus II Gonatas[4] and the widow of Lysimachus.[5] The Celts under chief Bolgius offered their withdrawal for money, but Ceraunus interpreted this as a sign of weakness and attacked. His army was defeated and he himself got killed.[6] Effectively without a king for the next two years, Macedon descended into anarchy.[7] The Celts, now causing havoc in the countryside without being able to storm the cities and fortifications,[8] were eventually defeated by the general Sosthenes, albeit not decisively.[6] Bolgius returned home.[9]

Brennus's successor was Cerethrius, who led the remainder of his warband into Thrace in 277. The Roman historian Justin reported how Antigonus II Gonatas hired Gallic mercenaries in Lysimacheia, possibly Cerethrius's warband. The same author, however, also described a battle at Lysimacheia beween Antigonos and a Celtic army that supposedly occurred in the same year, ending in the defeat of the latter. In any case, Antigonus left Lysimacheia strengthened[10] and seized the Macedonian throne with the help of several thousand Celtic mercenaries.[11] Another Gaulish contingent crossed the Bosphorus to fight for king Nicomedes I of Bithynia.[12]

Establishment in Thrace

editWhile the political situation of Thrace in the 3rd century remains confused and enigmatic, there is ample evidence that the kingdom of Tylis was just one of many political entities that existed in Thrace at that time.[13]

King Cavarus and demise

editReferences

edit- ^ Lund 1992, p. 1.

- ^ Lund 1992, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Waterfield 2021, p. 39.

- ^ Waterfield 2021, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Sánchez 2017, pp. 192–194.

- ^ a b Rankin 2002, p. 88.

- ^ Waterfield 2021, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Waterfield 2021, p. 40.

- ^ Sánchez 2017, p. 197.

- ^ Sánchez 2017, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Waterfield 2021, p. 119.

- ^ Sánchez 2017, p. 200.

- ^ Delev 2015, pp. 61–63.

Literature

edit- Delev, Peter (2015). "From Koroupedion to the Beginning of the Third Mithridatic War (281–73 BCE)". In Valeva, Julia; Nankov, Emil; Graninger, Danver (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Thrace. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 59–74. ISBN 978-1444351040.

- Emilov, Julij (2015). "Celts". In Valeva, Julia; Nankov, Emil; Graninger, Danver (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Thrace. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 366–381. ISBN 978-1444351040.

- Lund, Helene S. (1992). Lysimachus. A Study in Early Hellenistic Kingship. Taylor & Francis Ltd. ISBN 978-0415070614.

- Rankin, David (2002). Celts and the Classical World. Taylor & Francis.

- Sánchez, Fernando López (2017). "Galatians in Macedonia (280–277 BC). Invasion or Invitation?". In Toni Ñaco del Hoyo, Fernando López Sánchez (ed.). War, Warlords, and Interstate Relations in the Ancient Mediterranean. Brill. pp. 183–203.

- Waterfield, Robin (2021). The Making of a King. Antigonus Gonatas of Macedon and the Greeks. Oxford University.

- Jovanović The eastern Celts

https://www.academia.edu/21664091/The_Mal_Tepe_Tomb_at_Mezek_and_the_problem_of_the_Celtic_kingdom_in_South_Eastern_Thrace he Celtic presence in Thrace during the 3rd century BC in the light of new archaeological data

A small group of individuals fought in the revolt.[1]

It has even been proposed that its antisemitism was appropriated directly from Naszim, although this seems unlikely.[2]

These rhetorics were rooted in Islamic tradition[3] but also bore similarities to those found in contemporary fascism[4] and might have been anti-Jewish Axis propaganda during ww2[5]

- Gershoni, Israel (2014). "Introduction: An Analysis of Arab Responses to Fascism and Nazism in Middle Eastern Studies". In Israel Gershoni (ed.). Arab Responses to Fascism and Nazism. Attraction and Repulsion. pp. 1–34.

During WW2 the situation in Palestine stalled, largely because of the lack of an Arab leadership.[6]

- ^ Abu-Amr 1994, p. 3.

- ^ Gershoni 2010, p. 27.

- ^ el-Aswaisi 1998, p. 203.

- ^ Gershoni & Jankowski 2010, p. 223.

- ^ Herf 2009, p. 244.

- ^ El-Aswaisi 1998, p. 187.