A dragon kiln is a traditional Chinese form of kiln, mostly used for Chinese ceramics, especially in southern China. It is long and thin, and relies on having a fairly steep slope, typically between 10° and 16°,[1] up which the kiln runs. The kiln could achive the very high temperatures, sometimes as high as 1400° Centigrade,[2] necessary for high-fired wares including stoneware and porcelain, which challenged European potters of the same period, and some examples were very large, allowing up to 25,000 pieces to be fired at a time,[3] and up to 60 metres long.[4]

The type was developed during the period of the Kingdom of Wu, 220-280 CE, perhaps in Shangyu District in the northeast of Zhejiang province, where there were over 60 kilns by 200 CE. Thereafter it remained the main design used in southern China until the Ming dynasty. The pottery areas of south China are mostly hilly, whereas those on the plains of north China typically lack suitable slopes.[5]

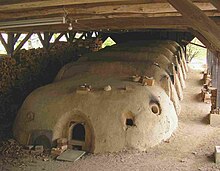

The kilns were usually built as a series of chambers with relatively flat floor levels, stepped as they ran up the slope, and with connecting doors to allow access to both the kiln-workers during loading and unloading, and the heat during firing. There might be up to 12 chambers, or merely a long staged chamber.[6] The main fire chamber was at the bottom, but there might be additional "stoke holes" to allow adding extra fuel at intervals up the slope, as well as peep holes to allow sight of the interior. At the far, top, end there was a chimney. The size and shape of the kilns and chambers within varied considerably. Firing was begun at the bottom end and moved up the slope.[7] The fuel might be wood or coal, which affected the atmosphere of the firing; coal giving a reducing atmosphere. Generally saggars were used,[8] at least in later periods.

The kilns allowed large quantities of pottery to be fired at high temperatures, but the firing was not usually even across the length of the kiln, which often produced different effects on pieces at different levels. Very often the higher chambers produced the better pieces, as they heated up more slowly.[9] As one example, the wide range of colours seen in Chinese celadon wares such as Yue ware and Longquan celadon is largely explained by variations in firing conditions.[10] The dragon kiln form was copied in Japan, in various types of climbing anagama kilns.

Notes edit

References edit

- Gompertz, G.St.G.M., Chinese Celadon Wares, 1980 (2nd edn.), Faber & Faber, ISBN 0571180035

- Hay, Jonathan, Sensuous Surfaces: The Decorative Object in Early Modern China, 2010, Reaktion Books, ISBN 1861898460, 9781861898463

- Kerr, Rose; Needham, Joseph; Wood, Nigel, Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 12, Ceramic Technology, 2004, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521838339, 9780521838337, google books

- Krahl, Regina: Oxford Art Online, section "Guan and Ge wares" in "China, §VIII, 3: Ceramics: Historical development"

- Medley, Margaret, The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics, 3rd edition, 1989, Phaidon, ISBN 071482593X

- Nillson, Jan-Eric, "Ge (Wade-Giles: ko) ware", in Chinese porcelain glossary, Gotheborg.com

- Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, 2007 (2nd edn), British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714124469

- Vainker, S.J., Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, 1991, British Museum Press, 9780714114705

- Valenstein, S. (1998). A handbook of Chinese ceramics, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. ISBN 9780870995149 (fully online)