| Somphospondyli Temporal range: Late Jurassic to Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

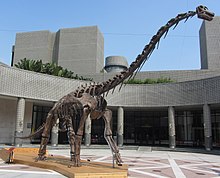

| Skeleton of Qiaowanlong | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Camarasauromorpha |

| Clade: | †Titanosauriformes |

| Clade: | †Somphospondyli Wilson & Sereno, 1998 |

| Genera | |

Somphospondylans are an extinct clade of titanosauriform sauropods that lived throughout the world from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) through the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) in North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia. The group was first defined in 1998 by Jeffrey A. Wilson and Paul Sereno; uniting Euhelopus and Titanosauria.[1]

The name Somphospondyli is derived from the Greek "somphos" meaning spongy and "spondylos" meaning vertebra.[1] One of the most unique features of Somphospondylans is the spongy composition of the presacral vertebrae.[1] Being titanosauriforms, members of Somphospondyli were among the largest land-dwelling dinosaurs known to exist.

Classification edit

Somphospondylans were first defined by Wilson & Sereno (1998) as "the most inclusive clade that includes Saltasaurus loricatus but excludes Brachiosaurus altithorax". The group includes titanosauriform sauropods that are more similar to Saltasaurus than to Brachiosaurus.[1] Mannion et. al (2013) describes Somphospondyli as one of the two sister clades of Titanosauriformes, with the other being Brachiosauridae.[2]

Characteristics edit

Somphospondylans share the following synapomorphies among tutanosauriforms:[1]

- Cervical neural arch laminae are reduced. In contrast with the cervical neural arches of Camarasaurus, those of Euhelopus and Malawisaurus are not as well-developed.

- Presacral vertebrae are composed of spongy bone. Saltasaurus vertebrae are characterized by a spongy interior, as are that of Euhelopus and titanosaurs.

- Anterior to mid-dorsal neural spines are posterodorsally inclined. These are observed in titanosaurs including Opisthocoelicaudia.

- Six sacral vertebrae (one dorsosacral added).

- Scapular glenoid are deflected medially. This differs from the laterally beveled scapular glenoid of Brachiosaurus.

Additional features found as diagnostic of this clade by Mannion et al. (2013) include the possession of at least 15 cervical vertebrae; a bevelled radius bone end; sacral vertebrae with camellate internal texture; convex posterior articular surfaces of middle to posterior caudal vertebrae; biconvex distal caudal vertebrae; humerus anterolateral corner "squared"; among multiple others.[2]

Cladistics edit

There exists some uncertainty in the classification of individual Somphospondylan sub-taxa.[2] Ligabuesaurus, Sauroposeidon, and Tastavinsaurus have all been previously recovered as basal Somphospondylans[3][4], but subsequent studies have shown weak relationships.[5] Sauroposeidon and Paluxysaurus were previously thought to be brachiosaurids, but later analyses have linked several of their synapomorphies to Somphospondyli.[5]

The following cladograms show Somphospondyli membership at increasing resolutions.

Wilson & Sereno (1998) edit

Adapted from Wilson & Sereno (1998), the cladogram below describes the relationships between Somphospondyli and its nearest relatives.[1]

| Sauropodomorpha | |

Taylor (2009) edit

The following cladogram constructed from Taylor (2009) highlights Brachiosauridae and Somphospondyli, the branching constituent clades of Titanosauriformes.[6]

| Titanosauriformes |

| ||||||

Elliott et. al. (2014) edit

Elliott et. al. (2014) derives a cladogram of Somphospondyli with a species-level resolution.[7]

| Somphospondyli |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dongbeititan dongi is shown here to be the most basal member of Somphospondyli. This result is derived from the analysis in Mannion et. al. (2013) but is subject to variability in its position.[2]

Paleogeography edit

Somphospondylans were absent from Antarctica and Australasia during the Late Jurassic, although titanosauriformes were found in Africa, Europe, the Americas, and Pakistan at that time.[2] The Middle Jurassic Ardley tracksite in the UK provides evidence for an earlier origin of titanosaurs, or derived somphospondylans[8]. Somphospondylans became the dominant sauropods by the Cretaceous, reaching every continent with the exception of Antarctica.[2]

Some Somphospondylans are believed to have existed exclusively in inland environments.[9] This is a result of “wide-gauge”trackway remnants of Somphospondylans found to be indicative of terrestrial sauropods.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Sereno, Paul C. (1998-06-15). "Early Evolution and Higher-Level Phylogeny of Sauropod Dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (sup002): 1–79. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011115. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ a b c d e f Mannion, P.D.; Upchurch, P.; Barnes, R.N.; Mateus, O. (2013). "Osteology of the Late Jurassic Portuguese sauropod dinosaur Lusotitan atalaiensis (Macronaria) and the evolutionary history of basal titanosauriforms". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 168: 98–206. doi:10.1111/zoj.12029.

- ^ Bonaparte, José F.; González Riga, Bernardo J.; Apesteguía, Sebastián (2006-06-01). "Ligabuesaurus leanzai gen. et sp. nov. (Dinosauria, Sauropoda), a new titanosaur from the Lohan Cura Formation (Aptian, Lower Cretaceous) of Neuquén, Patagonia, Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 27 (3): 364–376. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2005.07.004. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Canudo, José I.; Royo-Torres, Rafael; Cuenca-Bescós, Gloria (2008-09-12). "A new sauropod: Tastavinsaurus sanzi gen. et sp. nov. from the Early Cretaceous (Aptian) of Spain". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (3): 712–731. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[712:ANSTSG]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ a b D'emic, Michael D. (2012-11-01). "The early evolution of titanosauriform sauropod dinosaurs". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 166 (3): 624–671. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00853.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Taylor, Michael P. (2009-09-12). "A re-evaluation of Brachiosaurus altithorax Riggs 1903 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) and its generic separation from Giraffatitan brancai (Janensch 1914)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 787–806. doi:10.1671/039.029.0309. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Poropat, Stephen F.; Upchurch, Paul; Mannion, Philip D.; Hocknull, Scott A.; Kear, Benjamin P.; Sloan, Trish; Sinapius, George H. K.; Elliott, David A. (2015-04-01). "Revision of the sauropod dinosaur Diamantinasaurus matildae Hocknull et al. 2009 from the mid-Cretaceous of Australia: Implications for Gondwanan titanosauriform dispersal". Gondwana Research. 27 (3): 995–1033. Bibcode:2015GondR..27..995P. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2014.03.014. ISSN 1342-937X.

- ^ Powell, H. Philip; Gale, Andrew S.; Norman, David B.; Upchurch, Paul; Day, Julia J. (2002-05-31). "Sauropod Trackways, Evolution, and Behavior". Science. 296 (5573): 1659. doi:10.1126/science.1070167. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 12040187.

- ^ Upchurch, Paul; Mannion, Philip D. (2010/ed). "A quantitative analysis of environmental associations in sauropod dinosaurs". Paleobiology. 36 (2): 253–282. doi:10.1666/08085.1. ISSN 0094-8373.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

}}

This is a user sandbox of Jeanflow. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |