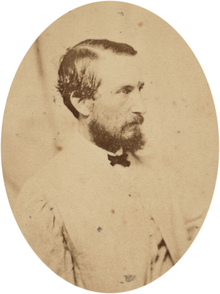

Henry James O'Farrell | |

|---|---|

Henry James O'Farrell, Sydney, about 1868, by Eugene Montagu Scott | |

| Born | 1833 Arran Quay, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 21 April 1868 Darlinghurst Gaol, Sydney, Australia |

| Occupation | Produce merchant |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Conviction(s) | Attempted murder of Prince Alfred |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

Henry James O'Farrell (1833 – 21 April 1868) was the first person to attempt a political assassination in Australia. On 12 March 1868, he shot and wounded Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, the second son and fourth child of Queen Victoria.[1]

Biography

editEarly life

editHenry James O'Farrell was born in 1833 at Arran Quay, on the north bank of the River Liffey in Dublin, Ireland, one of eleven children of William O'Farrell and Maria (née Flynn or Ronen).[2] His father was a butcher. In 1836 William and Maria O'Farrell migrated with their family across the Irish Sea to Liverpool, where William re-established his butchery at Edge Hill, near the city's docks.[3] In 1841 the O'Farrell family migrated to Australia, arriving in the newly-established settlement of Melbourne in the Port Phillip District. William set up a butcher's shop at the lower end of Elizabeth-street.[4] Maria O'Farrell died in March 1842 in Melbourne (when Henry was nine-years-old).[5]

By 1846 William O'Farrell had been appointed as a rate-collector in the Melbourne Town Council and in December 1848 he was appointed as a Town Auctioneer.[6][7][8] O'Farrell's children "were educated in a manner to fit them for positions higher than the trade followed by their father".[4] Young Henry O'Farrell received his early education at David Boyd's 'Melbourne Academy' school in Queen-street and then as a boarder at the Melbourne Analytical Seminary for General Education run by James McLaughlin, "to learn the classics, theology and elocution".[9] In 1848 and 1849 he attended the school-house at the rear of St. Francis' Chapel on the corner of Elizabeth and Lonsdale streets.[1][10]

William O'Farrell was an inaugural member of the St. Patrick's Society of Australia Felix, formed in Melbourne in 1842.[11] Sectarian tensions came to the surface in Melbourne after the formation of the Orange Society in 1843.[12] On 19 March 1846 Henry O'Farrell, as one of the St. Patrick's Society's "juvenile members", made his maiden speech at the Society's anniversary dinner.[13]

After the appointment of James Goold as the first Catholic Bishop of Melboune in 1848 the O'Farrell family developed close ties to the Catholic hierarchy in Melbourne. Bishop Goold conferred "minor orders prior to ordination" on Henry O'Farrell in December 1850 at St. Francis' Church, in a ceremony considered to be "on the path to priesthood".[14] In early 1851 O'Farrell was ordained as a sub-deacon and in 1852 as a deacon.[15] Henry's older brother Peter was admitted as a solicitor in September 1851 and began handling "the growing legal issues" of Bishop Goold and senior clergy and managing Church land acquisitions.[16][15]

As a young man O'Farrell "was regarded as genial, warm-hearted, and enthusiastic", but possessed of an abiding passion for Irish nationalism.[17]

Travel and business enterprises

editIn about 1853 O'Farrell left Melbourne for Europe, to continue his studies.[1] One account claimed he accompanied a French priest who was proceeding to France for the purpose of printing a Bible in the Maori language, translated at a Catholic missionary establishment in New Zealand.[18] O'Farrell visited the principal cities on the Continent, including Paris and Rome, and also travelled in England and Ireland. He was absent for about two years, returning to Victoria in about 1854.[1][17][19] O'Farrell's father died in July 1854 at South Melbourne (an event that may have prompted his return from Europe).[20]

In about 1855 Henry O'Farrell gave up his intention of joining the priesthood after he "had a dispute with the bishop" on some religious points". Soon afterwards O'Farrell went to Clunes "to learn sheep farming".[21] Soon afterwards, in partnership with his cousin Joseph Kennedy (or Rennett), O'Farrell established "a flourishing and lucrative business" as a grain merchant at Ballarat, operating a hay and corn store at the corner of Doveton-street and Market-square.[1][17] The produce business operated until about March 1867, with O'Farrell's health and mental state in marked decline during the last few years of its operation (probably exacerbated by the excessive drinking of alcohol).[22]

Hanify v. O'Farrell

editIn 1864 in a libel suit his brother Peter lost repute as a leading solicitor and fled from Melbourne; soon afterwards Kennedy died of delirium tremens.

'A Catholic' letter.[23]

Overview.[24]

Details.[25]

Increasing instability

editO'Farrell was described "as a man of gentlemanly demeanour, but exceedingly excitable, and of a very violent and misanthropical disposition". It was said of him that he was one who "having attached himself to an idea would pursue it at any cost, to himself or to others".[4]

O'Farrell was known to drink "very hard, and was subject to fits of delirium tremens". It was reported that "on one occasion he asked an acquaintance to lend him a pair of pistols to blow his brains out".[4] In January 1867 two of Henry's sisters were summoned to Ballarat by O'Farrell's medical attendants. His younger sister, Caroline Halley, later described how her brother did not recognise them at first. He was subject to various delusions, including asserting that "he had been poisoned by the doctors".[22]

Henry O'Farrell was an alcoholic, and had been released from a lunatic asylum immediately before the attempted assassination. O'Farrell had briefly been employed by his brother, a Melbourne solicitor, who had offices in Ballarat, and is therefore sometimes described as a law clerk. But O'Farrell's most recent occupation was selling fruit and vegetables in Ballarat's Haymarket.

The royal tour

editAt the beginning of 1867 Prince Alfred, Queen Victoria's second son, had embarked on a world cruise aboard the Galatea, a steam-powered sail-equipped frigate. With the Prince as captain the Galatea departed from Gibraltar in June 1867 and visited Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, the tiny island of Tristan da Cunha in the South Atlantic and the Cape Colony of southern Africa, before arriving at Adelaide in October 1867 to begin what was to be Australia's first royal tour.[26] The Prince visited the colonies of South Australia, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and Queensland, in an itinery consisting of numerous official engagements, civic receptions, dances, and public events. Details of the royal tour and the enthusiastic responses of the public were comprehensively recorded in the press.[27]

During the welcome ceremonies at Melbourne on 24 November 1867, 10,000 people gathered to meet him. An image of William of Orange defeating the Catholic armies at the Battle of the Boyne was erected on a hall in Melbourne. Someone fired shots from inside the hall into the Irish Catholic crowd who had gathered outside to throw stones at the hall, a Catholic boy was killed, and a riot between Irish Catholics and Protestants subsequently broke out.[28]

Assassination attempt

editThe Galatea arrived at Sydney from Tasmania on 21 January 1868 and berthed at Circular Quay. The Prince was welcomed by the Colonial Secretary, Henry Parkes, and the Governor, Lord Belmore, in an elaborate pavilion erected for the occasion. Later the Prince and his entourage were driven to Government House through the welcoming crowds.[29] O'Farrell was in the crowd that day. He later stated: "I had gone to Circular Quay on the day of the Prince's arrival in Sydney, and I intended to shoot him there, but the opportunity did not present itself".[30]

In March 1868 a public picnic was organised to raise public funds for the partially-completed Sailors' Home in Sydney. The organising committee extended an invitation to Prince Alfred to attend the event, which was accepted "and this event was looked forward to as one of the chief festivities in connexion with His Royal Highness's sojourn in the colony". The Sailors' Home Picnic was held on Thursday, March 12, at "the picturesque spot" of Clontarf, on the north shore of Sydney's middle harbour. Five steamers were engaged to convey the public from Circular Quay to the picnic ground during the day.[31] A large marquee had been added to the permanent buildings at the site to function as a "luncheon saloon" and a "handsome tent" was pitched opposite the beach, "for the convenience of His Royal Highness and suite". A number of yachts and steamers, decorated with flags and bunting, anchored nearby. By midday it was estimated between two and three thousand persons were present.[32]

Alfred and his entourage left the Galatea and sailed to the picnic ground aboard the steam-yacht Fairy, arriving at the Clontarf jetty at about two o'clock. They were met by members of the committee and escorted to the marquee where luncheon was provided. After the meal and a toast to "the health of Her Majesty the Queen", at about 3.20 p.m. Prince Alfred and his retinue proceeded to the tent "that had been set apart for their private use".[32]

When they reached the Royal tent Alfred conversed with several of the dignitaries, before he and Sir William Manning walked across to a clump of trees bordering the beach where a band was playing. The Prince handed Manning a cheque as a donation for the Sailors' Home. At that stage Henry O'Farrell, who had been standing amongst a group under the shade of the trees, walked up behind Alfred "and when he had approached to within five or six feet pulled out a revolver, took deliberate aim, and fired". The shot struck the middle of the Prince's back, about two to the right of his spine. He fell forward to his hands and knees, saying "My back is broken". Manning turned and sprang at O'Farrell, but lost his balance and fell. The would-be assassin took aim at Manning, but at that moment was grabbed by a bystander, a coach-maker named William Vial, who pinioned O'Farrell's arms to his side. In doing so the firearm discharged, the shot hitting the foot of George Thorne, who then fainted. Other bystanders also seized O'Farrell and there were cries of "lynch him" and "hang him" from the enraged crowd. The police, headed by Superintendent Orridge, took charge of the prisoner "and they had the greatest difficulty in preventing the infuriated people from tearing him limb from limb".[33] With difficulty O'Farrell was taken to the wharf and placed on board the Paterson steamer, by which time the clothing from his upper body had been torn off, his face and body were "much bruised" and blood "was flowing from various wounds".[34]

After he was shot, three or four men carried Prince Alfred to his tent where several doctors took charge of his care. When they examined the wound they found the bullet had penetrated to the right of the lower part of the spine, "traversing the course of the ribs" to the right of the abdomen where it lodged just below the surface.[33] The assassination attempt galvanised the crowd; "suddenly a joyous throng had been converted into a mass of excited people". Hundreds crowded around the tent awaiting the result of the medical examination. The Prince had never lost consciousness, and "finding the people so anxious about him", said: "Tell the people I am not much hurt, I shall be better presently". At about five o'clock Albert was placed on a litter and carried onto the deck of the Morpeth steamer and conveyed to Sydney.[34]

Afterwards

editAfter O'Farrell was apprehended police went to Tiernan's Currency Lass Hotel in central Sydney where they found the prisoner's few personal possessions in the room where he had spent the previous night. Investigations revealed O'Farrell had stayed at the Clarendon Hotel in George-street for most of the preceding week.[35]

Henry Parkes visited O'Farrell in the Watch-house where he was being held. O'Farrell's responses were brief and uninformative, but Parkes' lengthy statement to the press spoke of the possibilities of a Fenian plot.[35]

Vial (fob-watch).

The Prince was hospitalised for two weeks, and cared for by six nurses trained by Florence Nightingale, who had arrived in Australia that February under Matron Lucy Osburn.

The attack also caused great embarrassment in the colony, and led to a wave of anti-Catholic and anti-Irish sentiment, directed at all Irish people, including Protestant Loyalists. The next day, 20,000 people attended an "indignation meeting" to protest "yesterday's outrage". O'Farrell first claimed, falsely, to be under orders from the Fenian Brotherhood.[36] Although anti-British and anti-Royalist, he later denied being a Fenian.

Trial and execution

editO'Farrell was arraigned on March 26, on an indictment charging him with wounding, with intent to murder, Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh, at Clontarf on 12 March 1868. He pleaded not guilty to the charge and was brought up for trial in the Central Criminal Court on Monday, 30 March 1868, before Justice Alfred Cheeke. O'Farrell's defence team was headed by a barrister from Melbourne, Butler Aspinall.[22][37]

O'Farrell was tried at Sydney on 30 March 1868. The barrister with the thankless task of defending him was Butler Cole Aspinall, who had previously defended the rebel leaders of the Eureka Stockade. Aspinall sought to have O'Farrell found not guilty by reason of insanity. He cited O'Farrell's history of mental illness and recent release from an asylum. O'Farrell was convicted and sentenced to death by judge Alfred Cheeke.[38]

Prince Alfred himself tried unsuccessfully to intercede and save his would-be killer's life.[citation needed]

O'Farrell was hanged on 21 April 1868 in the Darlinghurst Gaol at the age of 35.[1]

Recovery of Prince Alfred

editPrince Alfred soon recovered, and returned home in early April 1868. On 24 March, the New South Wales Legislative Assembly voted to erect a memorial building. In order "to raise a permanent and substantial monument in testimony of the heartfelt gratitude of the community at the recovery of HRH", it was to be the Prince Alfred Hospital. Queen Victoria permitted the use of the term "Royal", so the memorial building was the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. It was built using funds raised by public subscription, and is today an important hospital in New South Wales.

Sir Henry Parkes, a Minister in the colonial government (and future Premier of New South Wales), stirred up persecution of Irish Catholics in the colony after O'Farrell's attack. Parkes claimed that the mad killer's initial claims of being Fenian were true and that there were extensive Fenian conspiracies at work. When Canadian politician and anti-Fenian D'Arcy McGee was killed by a Fenian on 7 April, the excitement increased. But soon the excitement died down, and the public began questioning Parkes' unsupported claims. These became an embarrassment and he resigned as a Minister in September.

Aftermath

editThe attempted assassination of Prince Alfred prompted widespread spontaneous and passionate responses in the Australian colonies. Hundreds of 'indignation meetings' were held in the weeks following the event, organised by local and political elites. It has been estimated that at least 250 indignation meetings were held, sixty percent of which took place within a week of the shooting. From the late 1850s telegraph technology had progressively linked the colonial capitals to their hinterlands and provided connections between the mainland colonies of eastern Australia. Newspaper accounts via "telegraphic dispatches" provided bulletins from other town and colonies, helping to "substantiate the idea of a national movement".[39]

The colonial government of New South Wales rushed through the Treason-Felony Act on March 18, which met with little opposition. However, there was considerable scepticism about the Act.[40]

The assassination attempt produced a wave of public sympathy and outrage in Australia. In a frenzy of Imperial loyalty “indignation meetings” were held around the country.

- One universal feeling of sorrow, shame, and rage pervades the community. The whole colony has been wounded in the person of its Royal guest. A crime, which every one will repudiate with horror, has shadowed our reputation.[41]

Brothers

editPeter Andrew Charles O'Farrell (b. 1828); September 1882 Archbishop Goold shooting; died 18 October 1898 in Melbourne.

On the evening of 21 August 1882 Archbishop Goold, in company with Father Daly, was strolling near Goold's residence at Brighton, when Peter O'Farrell came up to them and, pointing a revolver at the Archbishop, fired two shots in quick succession, one of which hit Goold's finger. O'Farrell ran away and was found about two hours later, hiding in a tea-tree scrub, and arrested.[42]

O'Farrell was tried on September 20 in the Central Criminal Court, charged with having shot at Archbishop Goold "with intent to kill him". The prisoner pleaded not guilty. O'Farrell claimed he "had not been actuated by any felonious intent", otherwise he could not have missed the Archbishop from a distance of only six feet. The jury, after retiring for about an hour, found the prisoner guilty "of unlawfully and maliciously wounding".[42][43]

Peter Andrew Charles O'Farrell died on 18 October 1898 in Melbourne of Bright's disease.[44]

In popular culture

editThe event was dramatised in the 1971 play Duke of Edinburgh Assassinated or The Vindication of Henry Parkes, written by Bob Ellis and Dick Hall.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f Mark Lyons; Bede Nairn (1974). "O'Farrell, Henry James (1833–1868)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Published first in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, (Melbourne University Press), 1974. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Family records, per Ancestry.com.

- ^ Harris, chapter 3 ('Henry, the Would-Be Priest'), page 1.

- ^ a b c d The Assassin of Prince Alfred, The Argus (Melbourne), 13 March 1868, page 5.

- ^ Died, Port Phillip Gazette (Melbourne), 23 March 1842, page 3.

- ^ Town Council, Melbourne Argus, 24 November 1846, page 4.

- ^ Town Auctioneer, The Argus (Melbourne), 19 December 1848, page 4.

- ^ District Petty Sessions, The Argus (Melbourne), 26 December 1848, page 3.

- ^ Harris, chapter 3 ('Henry, the Would-Be Priest'), pages 8-9, 12-13.

- ^ Melbourne: St. Francis' School, Geelong Advertiser', 21 December 1843, page 3.

- ^ "St. Patrick's Society of Australia Felix", Melbourne Times, 2 July 1842, page 2.

- ^ Mike Cronin and Daryl Adair (2004), The Wearing of the Green: A History of St Patrick's Day, New York: Routledge, ISBN: 041518004X, page 45.

- ^ O'Farrell's Antecedents in Melbourne, Ballarat Star, 27 March 1868, page 4.

- ^ Ordination at St. Francis Church, Melbourne Daily News, 23 December 1850, page 2.

- ^ a b Harris, chapter 3 ('Henry, the Would-Be Priest'), pages 19, 21.

- ^ Supreme Court: New Attorneys, Melbourne Daily News, 5 September 1851, page 2.

- ^ a b c O'Farrell's Career in Ballarat, The Age (Melbourne), 16 March 1868, page 6.

- ^ O'Farrell's Antecedents and Conduct, Newcastle Chronicle, 21 March 1868, page 2.

- ^ O'Farrell's Antecedents, Empire (Sydney), 23 March 1868, page 3.

- ^ Died, The Banner (Melbourne), 14 July 1854, page 8.

- ^ To the Editor of the Herald, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1868, page 5; letter to the editor from John Carfrae, Sydney, dated 18 March 1868.

- ^ a b c The Trial of Henry James O'Farrell, Sydney Mail, 4 April 1868, page 5.

- ^ The Debts of St. Patrick's College, The Age (Melbourne), 6 November 1862, page 5.

- ^ Hanify v. O'Farrell, The Leader (Melbourne), 7 March 1863, page 10.

- ^ Sending Threatening Letters, The Leader (Melbourne), 29 November 1862, page 11.

- ^ McKinlay (1970), pages 9-25.

- ^ Pentland (2015), pages 57-58.

- ^ "National Museum of Australia - First royal visit". www.nma.gov.au. National Museum Australia. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ McKinlay (1970), pages 131-137.

- ^ McKinlay (1970), page 175.

- ^ White (1868), page 1.

- ^ a b White (1868), page 2.

- ^ a b White (1868), page 4.

- ^ a b White (1868), page 5.

- ^ a b McKinlay (1970), page 172.

- ^ "Crimes of Passion". Historic Houses Trust. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ The Trial of Henry James O'Farrell for the Attempted Murder of His Royal Highness Alfred Ernest Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, Illustrated Sydney News, 20 April 1868, page 6.

- ^ Holt, H. T. E. "Cheeke, Alfred (1810–1876)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ Pentland (2015), pages 63, 65-66.

- ^ Pentland (2015), page 64.

- ^ Editorial, Sydney Morning Herald, 13 March 1868, page 4.

- ^ a b Attempted Assassination of Archbishop Goold, Leader (Melbourne), 23 September 1882, page 14.

- ^ O'Farrell's Career, The Tasmanian (Launceston), 30 September 1882, page 1070.

- ^ Death of Mr. P. A. C. O'Farrell, Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 19 October 1898, page 5.

- ^ Death of Mr. P. A. C. O'Farrell, Advocate (Melbourne), 22 October 1898, page 7.

- ^ Obituary: P. A. C. O'Farrell, Truth (Sydney), 23 October 1898, page 3.

Sources

- Steve Harris (2018), The Prince and the Assassin: Australia's First Royal Tour and Portent of World Terror, Melbourne: Melbourne Books, (ISBN 9781925556131).

- Brian McKinlay (1970), The First Royal Tour 1867-1868, Adelaide: Rigby Limited, (ISBN 0851790887).

- G. Pentland (2015), 'The indignant nation: Australian responses to the attempted assassination of the Duke of Edinburgh in 1868', English Historical Review, vol. 130, no. 542, pages 57-88.

- Henry L. White (1868), A complete report of the attempted assassination of H.R.H. Prince Alfred, Sydney.

Further reading

edit- Travers, Robert The Phantom Fenians of New South Wales (Kangaroo Press, 1986), 176p. ISBN 0-86417-061-0.

- Murphy, Peter Fenian Fear (Peter Murphy, 2018), 177p. ISBN 978-0-646-98824-5 (see also Fenian Fear web-site).