This is a commented version of the Music theory page as it existed on 1 September 2015.

I suggest that the main participants choose a color for their comments: I (Hucbald) chose darkred; Jerome Kohl chose darkviolet. Others may want to choose other colours. This will dispense us from signing each of our comments.

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music.

Christensen (Cambridge History of Wester Theory) quotes from Aristotles' Metaphysics as follows: "In characteristic dialectical fashion, Aristotle contrasted the kind of episteme gained by theoria with the practical knowledge (praktikè) gained through ergon. This was to be a fateful pairing, for henceforth, theory and practice would be dialectically juxtaposed as if joined at the hip. In Aristotle’s conceptual schema, the end of praktike is change in some object, whereas the end of theoria is knowledge of the object itself."

- Are you arguing that practice is not a concern of music theory? Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

I am merely quoting Christensen, I am not (yet) arguing about anything. As Christensen says, Aristotle does contrast theory with practice. This certainly is a point about which we should ponder.

- No doubt there are contrasts to be made, but it seems well established that music theory incorporates both “practices and possibilities.” "Music theory has always maintained its roots in both the mathematical nature of musically organized sound and in performance practice." (Crickmore, "A MUSICOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE AKKADIAN TERM sih ̮ puI" don’t see there’s much to ponder about that. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- Are you arguing that practice is not a concern of music theory? Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

It generally derives from observation of how musicians and composers make music, but includes hypothetical speculation. Most commonly, the term describes the academic study and analysis of fundamental elements of music such as pitch, rhythm, harmony, and form, but also refers to descriptions, concepts, or beliefs related to music.

This appears to invert the state of affairs: most commonly, the term refers to descriptions, etc., and in a more specific but more restricted sense to the academic study. Besides, the section on the history of music theory should discuss the changing role of music theory in universities and other such institutions. The section on history should explain that music theory was an important part of the quadrivium, and why; how it was progressively excluded from university teaching in the 17th and 18th century, and how and where it came back to the academic world in the 19th and early 20th century.

- "...should explain that music theory was an important part of the quadrivium, and why; how it was progressively excluded from university teaching in the 17th and 18th century, and how and where it came back to the academic world in the 19th and early 20th century" seems overly detailed for history section. Is the quadrivium a key aspect of the history from an international perspective? Jacques Bailhé 20:25, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Yes, certainly. The position of music theory in the quadrivium certainly deserves at least a short description. It shows that medieval theory retained the specific status that music theory had had in Antiquity, and this is similar, probably to its status in several non European traditions. Or else, we may as well drop everything out.

- I think digressing into the Quadrivium v. the Trivium, the changing role of theory in universities, etc., is, however fascinating, unnecessary detail in an overview of the worldwide history of music theory. The section does mention Boethius and that should be sufficient for the History section. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

Because of the ever-expanding conception of what constitutes music (see Definition of music), a more inclusive definition could be that music theory is the consideration of any sonic phenomena, including silence, as it relates to music.

Doesn't one write "any phenomenon", in this case? And I am not sure that silence can be considered a "sonic phenomenon"... The reason why "silence" is mentioned here appears to be that Definition of music quotes Cage's 4'33. It should be noted, there or here, that actual sound may not necessarily be a condition of music. Busoni considered that music has a written existence before being sounded, and some works are never played (never sounded); yet, they may not be considered "silent".

Yes, the singular "phenomenon" is correct. Due to falling standards of literacy, many English speakers can no longer tell the difference between singular and plural Greek words.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 21:49, 6 September 2015 (UTC)

- The plural is accurately used because the point is that there are many and varied phenomena to be considered. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

"any phenomena"? I think that "any" implies the singular. I trust that "the consideration of many phenomena" would have been more correct.

Aren't rests a type of silence? They're a perfectly legitimate topic of music theory. Actually, "phenomena" would be usable in this sentence (imagine substituting a more familiar plural such as "events"), but the word doesn't agree with "it" in the following clause; "they" would work. —Wahoofive (talk) 03:11, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- Wahoofive - Right you are. Good solution. Thanks. Jacques Bailhé 06:15, 17 October 2015 (UTC)

- Cage's 4'33" is not silent. The piece "organizes" ambient sound and asks us to consider whether the imposition of an organizing structure then transforms unorganized sound into music. Jacques Bailhé 20:25, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

The point is not whether or not 4'33 is silent, but whether it is relevant to music theory. The work certainly does not "organize" the ambient sound, it merely tries (not so successfully, I think) to draw attention to it. One may argue that 4'33 has theoretical implications, but these should be described and discussed (with references!). I was merely arguing that the original article, when it mentioned silence without quoting anything specific, may have done so because another article (Definition of music) mentioned 4'33.

- Discussion and references about Cage’s 4’33” are not in the History section or the Music theory article, but in the article on that work and in Definition of Music. Don’t see the point of discussing it further here. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

If the plural form is accepted, should it not then read "all phenomena"? Of course, silence is a legitimate concern of theory, but this runs up against a consistent problem throughout the article, which is the acceptance of any aspect of music as a legitimate concern of theory, without actually addressing the question of the theory of that aspect. If we allow this kind of thinking, then this article had better be expanded by several orders of magnitude, rather than being reined in to a manageable size.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 04:46, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- "a consistent problem throughout the article, which is the acceptance of any aspect of music as a legitimate concern of theory." This is not a problem, but a necessarily wide point of view. As we know from studies of world musics, our Western view of what is music, and therefore what aspects constiThistute music, needs to allow for the wide ranging concepts around the world of what music is. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

This article is not about the widely different definitions of "music" around the world, but about theory. The purpose of the article is not to produce theories about any kind of music, but to describe existing ones.

- The “widely different definitions of “music” around the world” are a critical aspect of music theory viewed in an international context. As you pointed out earlier, coming to grips with a workable definition of music—problematic as that may be—is fundamental to understanding what theory is talking about. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- "a consistent problem throughout the article, which is the acceptance of any aspect of music as a legitimate concern of theory." This is not a problem, but a necessarily wide point of view. As we know from studies of world musics, our Western view of what is music, and therefore what aspects constiThistute music, needs to allow for the wide ranging concepts around the world of what music is. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Music theory is a subfield of musicology, which is itself a subfield within the overarching field of the arts and humanities.

These "fields" need definition. Are they institutional fields in American universities, or domains of research, etc.

- They are defined in their own articles. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Or course. This was not my point. Rather, I question the hierarchy of subfields, which certainly is not endorsed by their own articles.

- Arts and Humanities contains the field of Musicology which contains Music Theory--right? That the sentence is talking about academic fields of study in general seems plain enough. IN Europe, they hold an annual European Conference on Arts & Humanities. If there are any differences in this hierarchy or division of fields between the U.S. and other countries' systems, do we need to explicate in this article? Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- They are defined in their own articles. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Actually, I think the statement is insupportable. From an historical point of view, music theory has been around since Ancient Greece, whereas the discipline of musicology is a creation of the late 19th century. Your question, Hucbald, is a good one, but supposes a framework of the present-day academy, without considering a broader historical view. On the other hand, all that is neede to cement this statement is a reliable source.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 04:58, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- Jerome, WP's article on musicology (linked in the sentence in question) reads "Musicology also has two central, practically oriented subdisciplines with no parent discipline: performance practice and research (sometimes viewed as a form of artistic research), and the theory, analysis and composition of music." That sentence comes from the Musicology article lead. The article's section "Subdisciplines" explains further. If the sentence from the Music Theory article needs a different reference, let me know. Jacques Bailhé 06:26, 17 October 2015 (UTC)

- Music theory was not invented in Ancient Greece--as the History section makes clear. Similarly, the statement that "musicology is a creation of the late 19th century" is contradicted by innumerable writings on the subject in a wide variety of previous times and cultures. Again, see the History section. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC

The article claims indeed that music theory predates written theory, a highly questionable point of view. "Musicology" certainly is a creation of the late 19th century, as is widely documented. It may have precedents, especially in the 18th century, but it would be a derision to call anything and everything "musicology". I am most curious to read more about those "innumerable writings" in "a wide variety of previous times and cultures". Can you provide one or two examples?

- The History section in the Music Theory article provides a number references that refer to what is commonly understood to be the process by which “orality” naturally precedes written documentation. But as previously mentioned on this talk page, Taruskin’s The Oxford History of Western Music, Vol. 1 opening chapter, offers a discussion of this in regard to Western music. Have a look at some of the papers at www. http://journal.oraltradition.org. Elsewhere, Sam Mirleman tells us “the Mesopotamian music texts are examples of what might be called “orality in written form”. It is well known that many cultures transmit knowledge (including musical knowledge) in an essentially oral form, which may be supplemented by writing. Certainly, this is the case with notation in its use almost everywhere, even in Europe. Indeed, it has been convincingly argued that Western Medieval musical culture relied to a great degree on oral transmission, despite the use of notation and written treatises. Similarly, in cultures such as ancient India and China, notation and theoretical writings survive, but any attempt to reconstruct and decipher these materials must be tempered by the knowledge that they originated in a musical culture in which notation was not intended to be understood by those who are uninitiated in the oral tradition. Similarly, the culture of ancient Mesopotamia was one in which orality certainly played an important role, despite our knowledge of tens of thousands of texts.” (“Tuning Procedures in Ancient Iraq.” p. 5. AAWM 2012 lecture) From the University of British Columbia’s Indigenous Foundations site (www. http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home.html)

“Ultimately, the divide between oral and written history is a misconception. Writing and orality do not exclude each other; rather they are complementary. Each method has strengths that depend largely on the situations in which it is used. They show similarities as well. As Stó:lō historian Naxaxahtls’i (Albert “Sonny” McHalsie) puts it, “The academic world and the oral history process both share an important common principle: They contribute to knowledge by building upon what is known and remembering that learning is a lifelong quest."3 Together oral and written methods of recalling and recounting the past have the potential to contribute greatly to the historical record. Since the mid20th century, particularly as a result of growing interest in the histories of marginalized groups such as African Americans, women, and the working class, Western academic discourse has increasingly accepted oral history as a legitimate and valuable addition to the historical record.4” 3. Albert “Sonny” McHalsie (Naxaxalht’i), “We Have to Take Care of Everything That Belongs to Us,” in Be of Good Mind: Essays on the Coast Salish, ed. Bruce Granville Miller (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007), 82. 4. Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson, eds., The Oral History Reader (London: Routledge, 1998), ix–xiii. Jacques Bailhé 16:35, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

Etymologically, music theory is an act of contemplation of music, from the Greek θεωρία, a looking at, viewing, contemplation, speculation, theory, also a sight, a spectacle.[1] As such, it is often concerned with abstract musical aspects such as tuning and tonal systems, scales, consonance and dissonance, and rhythmic relationships, but there is also a body of theory concerning such practical aspects as the creation or the performance of music, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, and electronic sound production.[2]

Palisca and Bent more precisely write: "Theory is now understood as principally the study of the structure of music. This can be divided into melody, rhythm, counterpoint, harmony and form, but these elements are difficult to distinguish from each other and to separate from their contexts. At a more fundamental level theory includes considerations of tonal systems, scales, tuning, intervals, consonance, dissonance, durational proportions and the acoustics of pitch systems. A body of theory exists also about other aspects of music, such as composition, performance, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation and electronic sound production."

- "principally the study of the structure of music" overemphasizes structure in relation to other aspects like melody and rhythm. "'...music theory' is an act of contemplation of music....'" is more accurate. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Would you doubt that "structure" involves melody and rhythm? If so, we are not speaking of the same thigs.

- Structure certainly involves aspects like rhythm and melody—although not necessarily those two aspects. My point is that Palisca/Bent open their definition of music theory with a statement that I think is unsupportable and unintentionally misleading: “Theory is now understood as principally the study of the structure of music.” Music theory is not necessarily “study,” but rather and specifically “theorizing” about music, in whatever form that may take, be it published paper, basic harmonic analysis, a critic’s appraisal of why a piece or performance was effective or not, etc. “Structure” is one of many aspects contemplated by theory. Limiting theory to “study” (implying formal academic work) and “structure” unnecessarily and unjustifiably restricts theory. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- "principally the study of the structure of music" overemphasizes structure in relation to other aspects like melody and rhythm. "'...music theory' is an act of contemplation of music....'" is more accurate. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

This is in the lead of the NG article, not in "1. Definitions" which does not exist: after the lead, the article continues with 1. Introduction (Palisca), noting the absence of overlap between four treatises; 2. Definitions (Palisca) describing a possible mapping of the field, inspired by that of Aristides Quitilianus, but a triffle too abstract to serve as an outline for the WP article.

A person who researches, teaches, or writes articles about music theory is a music theorist. University study, typically to the M.A. or Ph.D level, is required to teach as a tenure-track music theorist in an American or Canadian university.

Does this really belong here?

- No. —Wahoofive (talk) 03:22, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

Which part, Wahoofive? If you mean the second sentence, I agree with you; the first sentence seems unassailable.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 05:01, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- Both parts. The first sentence is just a dictionary entry, not necessary for understanding music theory. —Wahoofive (talk) 15:38, 9 September 2015 (UTC)

- No. —Wahoofive (talk) 03:22, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

Methods of analysis include mathematics, graphic analysis, and, especially, analysis enabled by Western music notation. Comparative, descriptive, statistical, and other methods are also used.

If musical analysis is meant here, there is a specific article; this here says either too much or not enough. First of all, one should explain the relation between music theory and music analysis. Then, why should mathematics come first? What about figuring (which is not really "graphic")? Why "enabled by Western music notation"? – notation does not "enable" analysis, it is part of it. And this fails to recognize that musical analysis may be a discipline in itself, not necessarily making use of "other [borrowed] methods".

The development, preservation, and transmission of music theory may be found in oral and practical music-making traditions, musical instruments, and other artifacts. For example, ancient instruments from Mesopotamia, China,[3] and prehistoric sites around the world reveal details about the music they produced and, potentially, something of the musical theory that might have been used by their makers (see History of music and Musical instrument).

The article History of music does not say a single word about the origin of theory. It says "The prehistoric is considered to have ended with the development of writing, and with it, by definition, prehistoric music." The word "theory" appears only once in the whole article: "...the sonata, the symphony, and the concerto, though none of these were specifically defined or taught at the time as they are now in music theory."

- Don't understand what bearing that has on an article about Music Theory and its history. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

The article Musical instrument never uses the word "theory".

- Musical instrument is in the lead to the article, not the History section and is there to point readers to Wikipedia’s discussion of the practical and conceptual aspects of instruments. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

In ancient and living cultures around the world, the deep and long roots of music theory are clearly visible in instruments, oral traditions, and current music making. Many cultures, at least as far back as ancient Mesopotamia, Pharoanic Egypt, and ancient China have also considered music theory in more formal ways such as written treatises and music notation.

This, which already has been much discussed, remains unacceptable. One might allow oneself to suspect the existence of a theory in oral and practical traditions, but certainly not observe there its "development, preservation and transmission". See also below.

- Music theory is not "suspected" to exist in oral and practical traditions. It inherently must. For an excellent discussion oral v. written, see Taruskin's opening chapter to “The Oxford History of Western Music” in Vol 1., “Music from the Earliest notations to the Sixteenth Century.” Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Taruskin discusses oral transmission, but never even hints at the idea of an "oral theory". Or do we not have the same version of the book?

- Taruskin writes, “…the early chapters are dominated by the interplay of literate and preliterate modes of thinking and transmission….” Modes of thinking = theory. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- I think this, and the next section, were added in a desperate attempt to make the article less ethnocentric on Western music. —Wahoofive (talk) 03:22, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

This is an important remark, Wahoofive, and I wouldn't like to appear to reject it. The fact is that Music Theory itself might well be (to a large extent) a characteristic of Western musical culture. A traditional culture, being less aware of its own history (or minding less) may be less prone to distanciate itself from its own practices and usages. There is nothing "etnocentric" to believe (as I tend to do) that Music Theory is characteristic of the West. Attempting to make the article less ethnocentric actually resulted in stretching the very definition of Music Theory outside its own limits. — Hucbald.SaintAmand (talk) 20:01, 9 September 2015 (UTC)

- The comment unabashedly announces a clear bias that I believe is unjustifiably limiting to thinking about music theory and its history and has no basis in historical fact, as the History section makes clear. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Jacques, I (and my students) have done a lot of work on non European theories. The corpus of Arabic theories, for instance, is minimal when compared to the Western one, even if one includes the most recent discoveries, about which published references ain't yet available. This is not a bias, it is a fact – a fact which certainly deserves some discussion in the article. The present section on "history of theory" makes nothing of this clear.

- I don’t understand why “The corpus of Arabic theories, for instance, is minimal when compared to the Western one,” is relevant to the History section, which only sets out a brief record of development and makes no value judgments. You write, “A traditional culture, being less aware of its own history (or minding less) may be less prone to distanciate itself from its own practices and usages. There is nothing "etnocentric"[sic] to believe (as I tend to do) that Music Theory is characteristic of the West.” Perhaps I misunderstand your point, but having read that a couple times now, it seems to contain bias against the sophistication of “traditional culture” and appears to want to put Western theory at the top of the heap. I imagine Western theory may well outweigh others in terms of sheer poundage, but as with your comment about the relative value of Arabic theory being somehow dependent on its size, I just don’t see that any such weighing is appropriate or useful. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

- The comment unabashedly announces a clear bias that I believe is unjustifiably limiting to thinking about music theory and its history and has no basis in historical fact, as the History section makes clear. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

- Music theory is not "suspected" to exist in oral and practical traditions. It inherently must. For an excellent discussion oral v. written, see Taruskin's opening chapter to “The Oxford History of Western Music” in Vol 1., “Music from the Earliest notations to the Sixteenth Century.” Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

History edit

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (December 2014) |

One wonders what the purpose of the contributor on prehistoric instruments was: most of his statements are disproved by the sources he quotes! As such, what follows confines to dishonesty (I try to remain polite). This all should disappear as fast as possible. At best, a short discussion might be given here, whether prehistoric music knows a level of "pre-theory" or not.

- Editors may err, but don't you think we must presume they are sincerely doing their best? Impugning any editor's efforts by suggesting dishonesty is out of line--especially in this case when you, Jerome, and I discussed all of what's in the History section at great length. The scholars cited discuss the music theory implications of these prehistoric instruments: pitch relationships, etc. If there is an error, by all means, correct it, but disparaging comments are unhelpful. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

I chekked most, if not all of the references given, and ascertained that they do not include what is claimed here they say. Until then, I had presumed whoever wrote this was sincere, but now I cannot believe that any more, as fully argumented below. If you think otherwise, can you provide full quotations?

- Editors may err, but don't you think we must presume they are sincerely doing their best? Impugning any editor's efforts by suggesting dishonesty is out of line--especially in this case when you, Jerome, and I discussed all of what's in the History section at great length. The scholars cited discuss the music theory implications of these prehistoric instruments: pitch relationships, etc. If there is an error, by all means, correct it, but disparaging comments are unhelpful. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Ancient instruments, artifacts, and later, depictions of performance in artworks give insight into early music-making. As early as the Paleolithic era, it appears people considered elements of music in some way. For instance, a bone flute with carefully placed finger holes found in Hohle Fels in Germany and dated c. 35,000 BCE,[4] may be a prehistoric example of the manufacture of an instrument to produce a preconceived set of pitches. For further discussion of Upper Paleolithic flutes, see d'Errico, et al. 2003, 39–48.

There is a specific article about these flutes, Paleolithic flutes (see also Prehistoric music, to where this could be moved: it has no place here. The paper by Conard (not Conrad!), Malina and Münzel [1] says nothing of what is claimed here. What it says is "As many as four very fine lines were incised near the finger holes. These precisely carved markings probably reflect measurements used to indicate where the finger holes were to be carved using chipped-stone tools. Only the partly preserved, and most distal, of the five finger holes lacks such markings." One cannot deduce from "carved markings to indicate where the finger holes were to be carved" that they were meant "to produce a preconceived set of pitches". Derrico e.a. [2] contest that the so called "flutes" fron Divje Babe cave in Slovenia were musical instruments at all; they claim that the Isturitz flutes may rather have been reed instruments or trumpets and that, therefore, their pitches hardly could be ascertained; they discuss whether the markings on these pipe could have had a symbolic meaning (and imply that they do not concern acoustic properties).

- The article reads, "a bone flute with carefully placed finger holes found in Hohle Fels in Germany and dated c. 35,000 BCE,[4] may be a prehistoric example of the manufacture of an instrument to produce a preconceived set of pitches. For further discussion of Upper Paleolithic flutes, see d'Errico, et al. 2003, 39–48." This makes clear that whether or not this flute demonstrates manufacture to produce preconceived pitches is a question of debate. The citation of d'Errico provides reference to an authoritative description and discussion of the flutes so readers may better understand their construction. I think you may have missed the following in the d"Errico article. “...such pipes could be more sophisticated than we thought....”p.42 “...finger-hole placement—at least half of the tuning equation—is preserved....” p.42 “Their variations in placement can hardly be dismissed as a mere symptom of a clumsy motion of technical incompetence....”p.43 "...it is conceivable that it could embody some form of limited musical notation: not a note-for-note notation of pitch or rhythm in the conventional musical sense, but nevertheless a representation of some feature of the music which the notator(s) felt moved to record." p.45 Or perhaps you were reading from a different d'Errico article (d'Errico et al 2009 BecEloq) in which he points out that "The so-called 'Neanderthal a fragment of an immature cave-bear femur from Divje Babe II Cave, Slovenia (Turk 1997, Kunei & Turk 2008) has proved to be rather the result of natural processes (d'Errico et al. 1998, Chase & Nowell 1998, d'Errico & Lawson 2006)." No doubt some of these finds are not manufactured musical instruments. Others decidedly are, as so much scholarship confirms. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

But manufacturing a musical instrument is no proof of the existence of a theory!

- In many instances, its tuning and other characteristics certainly are evidence of theory. The make had conceived theoretical ideas about music and created the instrument accordingly. Throughout music history, scholars draw conclusions about theory from the characteristics of instruments. The History section lists many references that do just that. Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

This whole section has bothered me ever since it was first introduced to the article. Now that you point it out, it is clear that the problem boils down to Original Research, since the editor is making assumptions about what the article might possibly mean, instead of sticking with what it actually says. This is a plain case of Failed Verification, and indeed the entire paragraph has no place in an article on music theory.

- There is no Failed Verification. The d'Errico article, not to mention of host of others, clearly discuss the what these flutes '"might possibly' mean." Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

- The article reads, "a bone flute with carefully placed finger holes found in Hohle Fels in Germany and dated c. 35,000 BCE,[4] may be a prehistoric example of the manufacture of an instrument to produce a preconceived set of pitches. For further discussion of Upper Paleolithic flutes, see d'Errico, et al. 2003, 39–48." This makes clear that whether or not this flute demonstrates manufacture to produce preconceived pitches is a question of debate. The citation of d'Errico provides reference to an authoritative description and discussion of the flutes so readers may better understand their construction. I think you may have missed the following in the d"Errico article. “...such pipes could be more sophisticated than we thought....”p.42 “...finger-hole placement—at least half of the tuning equation—is preserved....” p.42 “Their variations in placement can hardly be dismissed as a mere symptom of a clumsy motion of technical incompetence....”p.43 "...it is conceivable that it could embody some form of limited musical notation: not a note-for-note notation of pitch or rhythm in the conventional musical sense, but nevertheless a representation of some feature of the music which the notator(s) felt moved to record." p.45 Or perhaps you were reading from a different d'Errico article (d'Errico et al 2009 BecEloq) in which he points out that "The so-called 'Neanderthal a fragment of an immature cave-bear femur from Divje Babe II Cave, Slovenia (Turk 1997, Kunei & Turk 2008) has proved to be rather the result of natural processes (d'Errico et al. 1998, Chase & Nowell 1998, d'Errico & Lawson 2006)." No doubt some of these finds are not manufactured musical instruments. Others decidedly are, as so much scholarship confirms. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Similar bone flutes (gǔdí, 贾湖骨笛) from Neolithic Jiahu, China dated c. 7,000 BCE[5] reveal their makers progressively added more holes to expand their scales, structured pitch intervals closer to each other to adjust tuning, and could play increasingly expressive and varied music.[6] "Tonal analysis of the flutes revealed that the seven holes [in some of the flutes] correspond to a tone scale remarkably similar to Western eight-pitch scales."[7][8] These instruments[9] indicate their makers became familiar with acoustics and developed theories of music comparable to those of later times. Audio recordings of two of these flutes by Brookhaven National Laboratory are available here.

Once again, there exist a specific article on these instruments, where all this should be moved. The statement to the effect that some of these flutes played "a tone scale remarkably similar to Western eight-pitch scales" certainly cannot be found in the quoted article by Zhang, Harboolt, Wang and Kong, which merely says: "The carefully selected tone scale observed in M282:20 indicates that the Neolithic musician of the seventh millennium BC could play not just single notes, but perhaps even music." The fact that it is not even sure that these instruments "could play music" fully disproves that their makers "developed theories of music comparable to those or later times".

- The paper by Zhang et al, "The early development of music. Analysis of the Jiahu Bone Flutes" cited on the Jiahu flutes states: "...tonal tests indicate that they can play pitches that coincide closely with those of the modern musical scale. Comparing the notes of a twelve-tone scale in equal temperament with the tones produced by the bone flutes, one finds that the discrepancies are minor. That is to say, if one were to use the bone flutes to play modern music, the audience might not be able to detect the difference.” p.772); “The selection of a different keynote (i.e. the first note of a scale) adjusted the relation of the octaves and offered three different types of seven-tone scales. This innovation gave the flautists the freedom of using the same instrument to play music in a different key.” P.776 “the Jiahu flutes could play a musical

scale similar to that of modern times.”p777 It appears I misplaced quotation marks which I have now corrected. Thank you for pointing out the error in punctuation, but as you see from the quotes above, the statement correctly reflects the research in the papers cited. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

- The quote, “Tonal analysis of the flutes revealed that the seven holes correspond to a tone scale remarkably similar to the Western eight-note scale” comes from a news release posted by Brookhaven National Laboratory which can be found at https://www.bnl.gov/bnlweb/pubaf/pr/1999/bnlpr092299.html. That article is also the source of the audio file link which takes a reader to the article quoted and links to the audio recorded from playing the flutes. My original draft of the article places the references and quote in an order that was clear. I must have fouled this up in later edits. My apologies. I should rewrite the paragraph to put the references and quote back in the original order so there is no further confusion. Jacques Bailhé 06:05, 17 October 2015 (UTC)

This really is nonsense. One cannot both claim that widely different definitions of music exist in time and space, and at the same time fancy that prehistoric music played in keys like modern Western music. This is amateurism.

- Why nonsense? The same is true of the texts from Mesopotamia. "...musicologists have been able to produce credible reconstructions of the Mesopotamian tonal and tuning systems." (Crickmore, A MUSICOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE AKKADIAN TERM sih ̮ pu) Jacques Bailhé 16:24, 12 October 2015 (UTC) RE: the Hurrian Song and other texts from Mesopotamia, Sam Mirelman (“Tuning Procedures in Ancient Iraq.” AAWM 2012) tells us that: “…a small corpus of about twenty texts concerning strings, tuning and performance from ancient Iraq (loosely equivalent to “Mesopotamia”) and Syria has transformed our view of the earliest stages of music history. Not only is this corpus by far the earliest recorded expression of what might be called “music theory”….”(p.1) “…one particular text, which is undoubtedly the most important—the tuning text.”(p.1) “is a set of instructions for tuning a stringed instrument known as a sammû. The identification of this instrument is uncertain. I translate the term as a lyre, but all we know for sure is that it was a 9-stringed musical instrument.” (p.2)

“…To sum up, certain characteristics of Mesopotamian music theory are apparent from the tuning text which are undisputable: The tuning text demonstrates the fact that about 4000 years ago, human musical ability was not less advanced than it is today. Indeed, what has survived (by fortunate accident) from this period probably represents the culmination of a development of tuning and modal procedure which is considerably older than 4000 years. The tuning text applies to a particular instrument, the sammû; it is not a universal tuning manual for any instrument. According to this text, the instrument’s “mode” is defined by a particular tuning of the instrument’s open strings The dichord formed by 2 open strings spanning 5 consecutive strings is the basis of the system. The system is heptatonic: there are 7 modes, and the conception of string dichords spans a heptatonic system, where 7 is followed by 1, etc. There are nine strings; strings 8 and 9 are tuned together with strings 1 and 2, suggesting a unison or octave relationship. It also confirms the heptatonic nature of the system. The system is a modulation cycle which can be traversed through loosening or tightening. It demonstrates that the principle of gradual modulation through related modes was understood in this period. From the text itself the principle of modulation is conceived as the transformation of an instrument’s tuning through the alteration of a single string. If the accepted interpretation of the tuning text is correct, it would mean that relative pitch was important to the Mesopotamians, but precise pitch was not. For example, going through the loosening section from išartum through qablītum and then onto išartum again would result in the instrument being in išartum, but one semitone lower than at the start. This view is reinforced by the fact that there seems to be no term for precise pitch in Mesopotamian music theory; there are only terms for strings and dichords (which can also be modes depending on context). (p.6)Jacques Bailhé 16:39, 12 October 2015 (UTC)

In North America, similar flutes from the Anasazi Indian culture were found in Arizona and dated c. 600–750 CE, but again, suggest an older tradition. These instruments typically have six finger holes ranging one and a half octaves.[10] As with all these ancient flutes, it is likely an error to imagine the Anasazi flutes were limited to only as many tones as they have holes. Changes in embouchure, overblowing, and cross-fingering are common techniques on modern flutes like these that produce a much larger range of notes within an octave and in octaves above the fundamental octave.[11]

Once more, there is a specific article, Anasazi flute. The description by Gross concerns modern, more or less exact reconstructions of Anasazi flutes.

The earliest known examples of written music theory are inscribed on clay tablets found in Iraq and Syria, some of which contain lists of intervals and other details[12] from which "...musicologists have been able to produce credible reconstructions of the Mesopotamian tonal and tuning systems."[13] Tablets from Ugarit contain what are known as the Hurrian songs or Hurrian Hymns dated c. 1,400 BCE. An interpretation of the only substantially complete Hurrian Hymn, h.6, may be heard here. The system of phonetic notation in Sumer and Babylonia is based on a music terminology that gives individual names to nine musical strings or "notes", and to fourteen basic terms describing intervals of the fourth and fifth that were used in tuning string instruments (according to seven heptatonic diatonic scales), and terms for thirds and sixths that appear to have been used to fine-tune (or temper in some way) the seven notes generated for each scale.[14][15][16][17][18]

Mirelan ([3]) does not speak of "written theory", but only says that this corpus may be "by far the earliest recorded expression of what might be called “music theory”. That clearly indicates that (a) nothing earlier recorded music theory and (b) these tablets might express theory. Crickmore ([4]) continues, after the phrase quoted, "I assume additionally that, as in ancient Greece, music would also have had its theoretical branch, integrated by the ancient priest-mathematicians into their religious and cosmological speculations." That is to say that, in his opinion, the existence of a theory can only be assumed, and certainly doesn't directly follow from the fact that musicologists have been able to reconstruct the Mesopotamian tonal and tuning systems. In other words, neither of these authors share the idea expressed above, that theory may predate written testimonies, and neither of them is certain that this here is theory. That a Hurrian hymn has been recorded in recent times has nothing to do with theory. To claim that there existed a "system of phonetic notation in Sumer and Babylonia" is wishful thinking: the claim is based on only one case, MS 2340 in the Schoyen Collection (see [5], from which the sentence above is a literal quotation – the large number of references given notwithstanding).

- As you quote, the sentence reads, "The earliest known examples of written music theory are inscribed on clay tablets found in Iraq and Syria, some of which contain lists of intervals and other details." Is a list of intervals, terminology that gives individual names to nine musical strings or "notes", and to fourteen basic terms describing intervals of the fourth and fifth that were used in tuning string instruments inscribed on a clay table somehow not "written music theory"? You may personally reject the conclusions of the references, but they are indisputably the conclusions of the references. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Over time, many cultures began to record their theories of music in writing by describing practices and theory that was previously developed and passed along through oral tradition. In cultures where no written examples exist, oral traditions indicate a long history of theoretical consideration, often with unique concepts of use, performance, tuning and intervals, and other fundamental elements of music.

This is waking dream. Which cultures? How does one know that the theories had been developed through oral tradition? How do oral traditions indicate a history of theory? How does one know that untold concepts are unique?

- Again, see Taruskin's book mentioned above, or nearly any book on cultural development. Jacques Bailhé 20:44, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

The Vedas, the sacred texts of India (c. 1,000–500 BCE) contain theoretical discussion of music in the Sama Veda and Yajur-Veda. The Natya Shastra,[19] written between 200 BCE to 200 CE and attributed to Bharata Muni, discusses classes of melodic structure, intervals, consonance and dissonance, performance, and other theoretical aspects such a "shruti," defined as the least perceivable difference between two pitches.[20]

There are specific articles on Samaveda, Yajurveda and Natya Shastra. Neither of the first two contains the word "theory". The last reference (Bakshi) has only this to say about Samaveda: "The Sama Veda, the third veda after the Rig veda and the Yajur veda, is the Veda of Song. It consists of various hymns of the Rig Veda put to a different and more musical chant. The Rig Veda is the word, the Sama Veda is the song. The Sama veda is the origin of all Indian music." About the "shruti", it says "The earliest mention appears to have been made in Bharat muni’s Natyashastra (about 500 B.C.)", but this date of "about 500 BC" is fanciful (as can be seen above and in Natya Shastra).

- The article on Natya Shastra describes modes, tonic, and consonance/dissonance. These are topics of music theory as described on this page. Whether the word "theory" appears there strikes me as irrelevant. —Wahoofive (talk) 17:16, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

What I wrote is that neither the Samaveda nor the Yajurveda articles contain the word "theory". (Concerning my "obsession" about this, see below); and that the reference quoted to the effect that they deal with theory, Bakshi, says nothing of the kind. The case of Natya Shastra is different. — Hucbald.SaintAmand (talk) 17:57, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- The article on Natya Shastra describes modes, tonic, and consonance/dissonance. These are topics of music theory as described on this page. Whether the word "theory" appears there strikes me as irrelevant. —Wahoofive (talk) 17:16, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

The music of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica is known through the many instruments discovered. Thirty-two condor-bone flutes and thirty-seven cornet-like instruments made of deer and llama bones have been recovered from a site at Caral, Peru dating to c. 2,100 BCE.[21][22][23] Flute No. 15 produces five distinct fundamental tones. A Mayan marimba-like instrument (c. 350 CE), made from five turtle shells of decreasing sizes suspended on a wooden frame, has been discovered in Belize.[24]

I myself (Hucbald) studied several pre-Columbian instruments, and I blew some of them. I can confirm that they play several different pitches, but this not only says nothing about theory, it even says nothing about pre-Columbian music which remains utterly unknown. One cannot even be sure that these objects are musical instruments.

Later artwork depicts ensemble and solo performance. Taken together, this evidence does not in itself demonstrate anything about music theory in Mesoamerica from at least 2,000 BCE, though "...it is widely accepted that finds and depictions of ancient musical instruments are not only markers of musical traditions in space and time. … The information obtained from the archaeological record can be deepened considerably when ancient scripts, historical treaties, and other written sources concerning music are related. Such documents offer notes on performance practices and their sociocultural contexts. For some cultures, hints concerning ancient music theory and musical aesthetics may also be found."[25]

The full quotation from Both reads: "it is widely accepted that finds and depictions of ancient musical instruments are not only markers of musical traditions in space and time – especially when the archaeological contexts are well documented – but also a valuable means for experimentally testing ancient playing techniques. [...] The information obtained from the archaeological record can be deepened considerably when ancient scripts, historical treaties, and other written sources concerning music are related. Such documents offer notes on performance practices and their sociocultural contexts. For some cultures, hints concerning ancient music theory and musical aesthetics may also be found and, if ancient notations are related, even clues to aspects of musical structures are provided." This is a general statement, which by no means concerns Mesoamerica particularly; and the words "hints concerning ancient music theory" is the only appearance of the word "theory" in the whole article (see [6]).

Music theory in ancient Africa can also be seen in instruments .[26] The Mbira, a wood or bamboo-tined instrument similar to a Kalimba, appeared on the west coast of Africa about 3,000 years ago, and metal-tined lamellophones appeared in the Zambezi River valley around 1,300 years ago.[27] In the 20th century, these instruments produce a number of tones, ranging to 32 separate pitches, and demonstrate a great variety of tunings—tunings "so dissimilar as to offer no apparent common foundation", something that might have been expected at least by 1932.[28] The djembé, a common type of drum, likely originated from earlier, extremely ancient drums.[29] Djembé ensembles create complex polyrhythmic patterns,[30] but produce a variety of pitches depending on size and playing technique, usually producing at least three separate tones.[31] African music theory is also preserved in oral and cultural traditions that are one example of the great variety of concepts of fundamental aspects of music around the world.[32]

See the comments added in the text itself, in general to the effect that page numbers should be added. But it is extremely unlikely that Kubik (which is a two volume collection of articles by various authors) says that African theory can be "seen" (?) in African instruments. That the Mbira and metal-tined lamellophones appeared thousands of years ago has nothing to do with theory. What these instruments are discovered to produce in the 20th century has nothing to do with the early history of theory. How can the many African oral traditions form "one example"? What are "oral and cultural traditions"? Chernoff's book is about African traditions today; and, in any case, "fundamental aspects of music of the world" may not at all be concerned with theory.

In China, a variety of wind, string, percussion instruments, and written descriptions and drawings of them from the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th to 11th century BCE), show sophisticated form and design.[33] During the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–256 BC), a formal system of court and ceremonial music later termed "yayue" was established. As early as the 7th century BCE, a system of pitch generation was described based on a ratio of 2:3 and a pentatonic scale was derived from the cycle of fifths,[34] the beginnings of which appear in 7,000 year-old Jiahu bone flutes. In the tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng (5th century BCE), among many other instruments, a set of bronze chime bells were found that sound five complete seven note octaves in the key of C Major and include twelve semitones.[35] The Analects of Confucius, believed to have been written c. 475 to 221 BC, discuss the aesthetics of what Confucius considered the most benevolent form and use of music, in contrast to popular music of his time—an example of early music criticism and consideration of aesthetics.[36][37]

We arrive here on slightly safer ground. However, the book by Thrasher does not include the word "theory"; the reference to Randel is a reference to the Harvard Dictionaly of Music as a whole! I cannot figure out how "the beginnings" of a pentatonic scale derived from the cycle of fifths can appear in a flute. The Yi Zeng bells are certainly not "in the key of C Major" (!!!), especially if they "include twelve semitones". I think that aesthetics is a domain of philosophy, not of theory. There may be a lot more to say about early Chinese theory.

- These bell instruments (Bianzhong) are far more sophisticated than first thought: “(1) a norm tone of F4 ~ 345 Hz (ca. F4-20 Cent, re modern A4 = 440 Hz), (2) a six-tone standard scale of D-E-F-G-A-C with F#, G#, A#, B, C#, and D# as accidentals, and (3) a third-oriented tuning with equally tempered fifths (~696 Cent) in the series CGDAE.” (Martin Braun, “Bell tuning in ancient China: a six-tone scale in a 12-tone system based on fifths and thirds” 2003 http://www.neuroscience-of-music.se/Zengbells.htm) The set he refers to are known as the “Zheng bells,” a set of 65 with 130 discrete strike tones from the tomb of the Marquis Ti of Zeng c. 433 BCE. Many other sets of varying composition have been found dating to c. 1,500 BCE. “Analysis of the measured tone data [of the Zheng Bells] shows that the 33 melody bells in the middle tier repeat the six-tone scale D-E-F-G-A-C eight times.” (ibid) Apparently, the bells are arranged in accompaniment and melody sections. “The apparent order of octave repetition reveals a subdivision of the three bell rows of the middle tier into 9 groups of 3-5 bells each, as shown in the table below. One can assume that in some performance types there was a player for each of these 9 subgroups. That way it was possible to play eight-fold "tutti" melodies, very similarly as today with saron instruments in a Gamelan orchestra….Interestingly, the DEFGAC scale uses the same tones as the famous hexachord of Guido of Arezzo from the early 11th century CE.” (ibid) The article concludes, “The 65 Zeng bells prove that about 2500 years ago the Chinese had fifth generation, fifth temperament, a 12-tone system in musical practice (not just in theory), a norm tone for an orchestral ensemble, an integration of fifths and thirds in tuning, and a preference of pure thirds over pure fifths.” (ibid) Making conclusions about them before reading the relevant research is counterproductive. Any help better summarizing the most important aspects of these bells in one sentence for the History section will be much appreciated. Jacques Bailhé 16:21, 14 October 2015 (UTC)

- I don't understand your obsession with finding the word "theory" in the texts cited. Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum doesn't use the word "theory," but it's obviously a significant contribution to the topic. In any case, for texts in foreign languages it's a translator's judgment whether to use a particular word in English. —Wahoofive (talk) 17:16, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

Of course, Fux does not use "theory", nor probably its Latin equivalent. But I do believe that any text quoted as a reference to the effect that Fux was a theorist should somehow speak of "theory" or of "theorist". Here, for instance, Thrasher's book (in English!) is quoted to at least imply that the Chinese instruments are relevant to theory; however he himself never speaks of theory... But you are right, I am becoming too upset by this all... — Hucbald.SaintAmand (talk) 17:57, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- The topic of the section is "theory." Doesn't it make sense when referring to the topic to use that word? Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Yes, precisely. This is why I think that a book [Trasher] should only be said to concern theory if it used the word...

- I can't understand why a book, or anything else for that matter, "should only be said to concern theory if it used the word..." As an example, I wrote in the History section that "During the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–256 BC), a formal system of court and ceremonial music later termed "yayue" was established. As early as the 7th century BCE, a system of pitch generation was described based on a ratio of 2:3 and a pentatonic scale was derived from the cycle of fifths,[34]" Whether or not the word "theory" was used in those writings I do not know. Whether they used a word with a similar meaning I do not know. But doesn't it seem appropriate to consider that they were describing aspects of what we call "theory"?Jacques Bailhé 16:21, 14 October 2015 (UTC)

- I don't understand your obsession with finding the word "theory" in the texts cited. Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum doesn't use the word "theory," but it's obviously a significant contribution to the topic. In any case, for texts in foreign languages it's a translator's judgment whether to use a particular word in English. —Wahoofive (talk) 17:16, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

Around the time of Confucius, the ancient Greeks, notably Pythagoras (c. 530 BCE), Aristotle (c. 350 BCE),[38] Aristoxenus (c. 335 BCE),[39] and later Ptolemy (c. 120 CE),[40] speculated and experimented with ideas that became the basis of music theory in Middle Eastern and Western cultures during the Middle Ages as can be seen, for example, in the writing of Boethius in 5th century Rome[41] and Yunus al-Katibin 7th century Medina.[42] Middle Eastern and Western theory diverged in different directions from ancient Greek theory and created what are now two distinctly different bodies of theory and styles of music.

More could be said about Greek theory. Boethius certainly does not show anything about theory during the Middle Ages: he was dead, the poor guy. Yunus al-Katibin must be a joke: as can be read in Shiloah, his name is Yunus al-Katib, and his "Book of melodies" is lost (as are all of his other writings).

- The sentence read, "...Yunus al-Katibin 7th century Medina." Should have read, "Yunus al-Katib in 7th century Medina." Thank you for pointing out the typo which I have now corrected.Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Remains, besides the typo, that his book is lost...

- Are you arguing that Yunus al-Katib is not recognized as a significant theorist in Arabic music and that we don't know something of what his book said? What is your point? - Jacques Bailhé 07:05, 17 October 2015 (UTC)

- Boethius is dated 480–524 AD, the beginning of the Middle Ages (5th to the 15th century per Wikipedia) and so was very certainly not dead. Your comment that "Boethius certainly does not show anything about theory during the Middle Ages" is incorrect. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

- The sentence read, "...Yunus al-Katibin 7th century Medina." Should have read, "Yunus al-Katib in 7th century Medina." Thank you for pointing out the typo which I have now corrected.Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

As Western musical influence spread throughout the world in the 1800s, musicians adopted Western theory as an international standard—but other theoretical traditions in both textual and oral traditions remain in use. For example, the long and rich musical traditions unique to ancient and current cultures of Africa are primarily oral, but describe specific forms, genres, performance practices, tunings, and other aspects of music theory.[43][44]

If other theories must be mentioned (they certainly must), I'd not choose Africa as the only example.

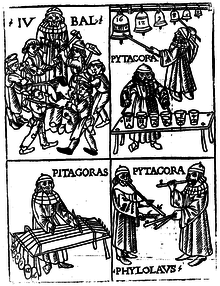

Major contributors to the field include the ancient Greeks: Archytas, Aristotle, Aristoxenus, Eratosthenes, Plato, Pythagoras, and later Ptolemy. The Middle Ages of Europe had Boethius, Franco of Cologne, Guido of Arezzo, Hucbald of Saint-Amand, Jacob of Liège, and Jean de Muris. Later in Europe, Zarlino, Rameau, Werckmeister, and Fux helped further musical knowledge. More recently, Riemann, Schenker, Boulanger, and Schoenberg contributed (see List of music theorists). Musical theorists in India include Bharata Muni, Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande, Purandara Dasa, and Sharngadeva. The Middle East had Ibn Misjah, Ibrahim al-Mawsili. and his son Ishaq, Yunus al-Katib, Ibn Sina (known in Europe as Avicenna)[citation needed]. China had Confucius, Yong Menzhoue, and Cao Rou.[citation needed]

Links to List of music theorists (which is a list of Western theorists) and the categories Category:Chinese_music_theorists, and the category Category:Musical_theorists_of_medieval_Islam might be more useful. At least, whoever wrote the above quoted me.

Hucbald.SaintAmand (talk) 09:02, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

Thanks for the links. — Hucbald.SaintAmand (talk) 17:57, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

Fundamentals of music edit

Music is composed of aural phenomena, and "music theory" considers how those phenomena apply in music. Music theory considers melody, rhythm, counterpoint, harmony, form, tonal systems, scales, tuning, intervals, consonance, dissonance, durational proportions, the acoustics of pitch systems, composition, performance, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, electronic sound production, etc.[45]

It is not obvious that music is composed of aural phenomena: musical works that are never heard also may be music. It might be better to write that "music is composed of sound phenomena", but even that might be discussed. Busoni said that music exists before being performed (but he was obviously refering to written music); the question relates to the ancient philosophical question whether a tree falling in a forest without anyone to hear it makes a sound. In any case, defining "music" cannot be the purpose of this article: the only sensible thing to do appears to be to take the definition of music as understood.

Palisca and Bent are more precise and might be quoted in full: "Theory is now understood as principally the study of the structure of music. This can be divided into melody, rhythm, counterpoint, harmony and form, but these elements are difficult to distinguish from each other and to separate from their contexts. At a more fundamental level theory includes considerations of tonal systems, scales, tuning, intervals, consonance, dissonance, durational proportions and the acoustics of pitch systems. A body of theory exists also about other aspects of music, such as composition, performance, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation and electronic sound production." This quotation has the advantage of introducing some hierarchy, namely between "the structure of music", "a more fundamental level" and "other aspects of music", which might be used here to organize the article.

Another possible source might be Guido Adler's paper about Musikwissenschaft, where he distinguished "historical" and "systematic" knowledge of music. Since then, it seems more or less understood that "theory" proposes a "synchronic" view of music (Saussure's terminology), as opposed to the "diachronic" (historic) view. A discussion of this of course belongs to the lead of the article.

Hucbald.SaintAmand (talk) 18:34, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

Strictly speaking, this belongs to either the Definition of music or the Philosophy of music articles, though it is difficult to imagine how to define "theory of music" without first establishing what we mean by "music". Palisca and Bent do provide an admirably thought-out definition, and I agree that the hierarchy would be useful in organizing this article. It may not be necessary to quote it in full, though that is one option. I would vote for using this, one way or another, as the basis for organizing the article and also for setting some limits to our topic. As for discussing things in the article's lead, keep in mind that the Wikipedia guidelines say that the lead should only summarize what is already discussed more fully in the body of the article. The diachronic/synchronic distinction appears to be a sound means of distinguishing musicology from theory (cf. my sour comment about the "branch of musicology" claim in the lead), though of course we must beware of "improper synthesis" by noting the similarity of Saussure and Adler's thinking.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 20:34, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

For sure, it will eventually appear impossible to rewrite Music theory without attacking other articles as well (this is one of our major problems). It is clear that the final content of the lead cannot be decided before the rest is rewritten, but we may already have ideas. As to "improper synthesis" and "original research", I think that WP policy here must be taken with a level of disrespect. It is impossible to (re)write an article on Music Theory, that exists nowhere else, without some level of novel synthesis. It is a matter of auctoritas, as we said in my youth, in the Carolingian Era: quote authorities and well known statements, in new arrangements that result in original ideas. That's what my Musica was about, despite what the young Gustave Reese wrote about it (Music in the Middle Ages, p. 126: "Many theoretical works, out of respect for auctoritas, duplicated what had been written before. Such works, Hucbald's included, etc."). Poor Gustave, who didn't realize that my Musica is still quoted more than a thousand years after I wrote it; I doublt his Music in the Middle Ages will survive that long. I'll have a word with him here in Paradise: he must now be out of the Purgatory, I hope. — Hucbald.SaintAmand (talk) 06:35, 8 September 2015 (UTC)

As general note, when I first circulated a draft of the History of Music section on the Talk page of the Music Theory article, I asked for suggestions and help. Instead, I was mostly accused of dishonesty, lying, and generally berated. I don't think that's helpful to the creation of the article and roundly discourages other people from pitching in. That's not good for Wikipedia. You will note that many of the criticisms above are put rudely -- to say the least -- and very few specific suggestions for improvements in the article are offered. That's not helpful. I would hope that when an editor comes along something that seems mistaken or inappropriate, they either correct it or start a discussion to see what the original contributor intended. Jacques Bailhé 20:15, 11 October 2015 (UTC)

Jacques, I don't remember whether I saw your draft of the History of Theory section; I think I came only later in the discussion. Since then, however, much has been said about (and against) that section, without much reaction. To me, WP articles are by essence anonymous. If you feel that you are the author of the History of Theory section, I am sorry. But I do feel concerned. You may know that members of the American Society for Music Theory withdraw from Wikipedia when they realized that no serious correction was possible (see [7].) Jerome and I have long argued that the History of Theory section is inadequate. After a while, the frustration becomes overwhelming.

Further comments to this added on the talk page hereby.

Pitch edit

The article cannot dispense to deal with pitch, but most of what is said at present concerns the acoustical aspects of pitch, not its musical aspects. A clear distinction should be made between the two. One of the main matters to consider concerns the relation between relative and absolute pitch – or, better, the absence or existence of pitch standards, leading to the creation of a standard pitch in the 19th century. Among the topics that might be covered, I can think of these:

- Pitch may not be an important category in all musics of the world.

- Pitch standards were not discussed in Europe before the early 16th century (Arnolt Schlick): this raises question about how questions of pitch were treated before, if they were.

- Pitch standards may have been discussed in China long before they were in the West. I don't know about that, but it would seem that pitch in China was of some politic importance (?).

- The question of pitch apparently arose as a result of the usage of the organ for the accompaniment of choirs: it has to do with the requirements of transposition. There are articles about this in The Organ Yearbook.

- Temperament, like pitch, is a question that primarily concerns instruments of fixed pitch (keyboards, harp, etc.)

- A word might be said of the evolution of pitch standards from the 16th century to today, but that really belongs to another article.

- An important question is that of playing in tune, which, if applied too strictly, results in a shift in pitch. See the famous letter of Benedetti to Cipriano de Rore.

- Etc.

Pitch is the lowness or highness of a tone, for example the difference between middle C and a higher C. The frequency of the sound waves producing a pitch can be measured precisely, but the perception of pitch is more complex because we rarely hear a single frequency or pure pitch. In music, tones, even those sounded by solo instruments or voices, are usually a complex combination of frequencies, and therefore a mix of pitches. Accordingly, theorists often describe pitch as a subjective sensation.[46]

These references could be replaced by a quotation of the ASA definition of pitch: "12.1 Pitch is that attribute of auditory sensation in terms of which sounds may be ordered on a scale extending from low to high. Pitch depends primarily on the frequency of the sound stimulus, but it also depend on the sound pressure and waveform of the stimulus". But this definition really is an acoustical one. What pertains to music theory may be the "tone", defined by the ASA as "13.1 (1) A tone is a sound wave capable of exciting an auditory sensation having pitch. (2) A tone is a sound sensation having pitch". [ASA acoustical definitions concern Pitch in chapter 12, Music in chapter 13.] There is no reason to assume that the sensation of pitch is subjective because tones usually are complex. The reference quoted, Hartmann, does not define subjective sensations by the complexity of the tones, but by the presence of "aural harmonics" (i.e. harmonics produced whithin the ear). This, in any case, belongs to the specific article on pitch (music) [which, strictly speaking, may not be about music, but acoustics], and certainly not to this one on music theory.

Most people appear to possess relative pitch, which means they perceive each note relative to some reference pitch, or as some interval from the previous pitch. Significantly fewer people demonstrate absolute pitch (or perfect pitch), the ability to identify pitches without comparison to another pitch. Human perception of pitch can be comprehensively fooled to create auditory illusions. Despite these perceptual oddities, perceived pitch is nearly always closely connected with the fundamental frequency of a note, with a lesser connection to sound pressure level, harmonic content (complexity) of the sound, and to the immediately preceding history of notes heard.[47] In general, the higher the frequency of vibration, the higher the perceived pitch. The lower the frequency, the lower the pitch.[48] However, even for tones of equal intensity, perceived pitch and measured frequency do not stand in a simple linear relationship.[49]

This does not pertain to music theory, despite what I write above: I am not aware of any music theory taking in account whether pitch is perceived as absolute or relative, and the perception of absolute vs relative pitch is a question studied also outside any musical context. The question of relative vs absolute pitch, from the point of view of music theory, is not one of individual perception, but one of the existence, or not, of pitch standards.

Intensity (loudness) can change perception of pitch. Below about 1000 Hz, perceived pitch gets lower as intensity increases. Between 1000 and 2000 Hz, pitch remains fairly constant. Above 2000 Hz, pitch rises with intensity.[50] This is due to the ear's natural sensitivity to higher pitched sound, as well as the ear's particular sensitivity to sound around the 2000–5000 Hz interval,[51] the frequency range most of the human voice occupies.[52]

Neither does this belong to music theory. Music (and its theory), on the contrary, usually neglects possible differences in pitch perception arising from variations in intensities – which is why the same melody could be played f or p. [It is interesting to note that, in bowed instruments, pitch is not affected by intensity, so long as the bow does not exert excessive pressure. Wind instruments are usable only in the range in which intensity does not affect pitch too much. Otherwise, crescendos would result in shifts of pitch which would make music impossible.

The difference in frequency between two pitches is called an interval. The most basic interval is the unison, which is simply two notes of the same pitch, followed by the slightly more complex octave: pitches that are either double or half the frequency of the other. The unique characteristics of octaves gave rise to the concept of what is called pitch class, an important aspect of music theory. Pitches of the same letter name that occur in different octaves may be grouped into a single "class" by ignoring the difference in octave. For example, a high C and a low C are members of the same pitch class—the class that contains all C's. The concept of pitch class greatly aids aspects of analysis and composition.[53]

Defining pitch class is not so much a matter of "the unique characteristics of octave" (which ain't defined in the above) as a matter of semiotics: tones (rather than pitches) distant by one octave are considered to share common semiotic characteristics, as is often denoted by their having the same denomination. This is implied above in the mention of "pitches of the same letter name", but should be further described in semiotic terms.

Although pitch can be identified by specific frequency, the letter names assigned to pitches are somewhat arbitrary. For example, today most orchestras assign Concert A (the A above middle C on the piano) to the specific frequency of 440 Hz, rather than, for instance, 435 Hz as it was in France in 1859. In England, that A varied between 439 and 452. These differences can have a noticeable effect on the timbre of instruments and other phenomena. Many cultures do not attempt to standardize pitch, often considering that it should be allowed to vary depending on genre, style, mood, etc. In historically informed performance of older music, tuning is often set to match the tuning used in the period when it was written. A frequency of 440 Hz was recommended as the standard pitch for Concert A in 1939, and in 1955 the International Organization for Standardization affirmed the choice.[54] A440 is now widely, though not exclusively, the standard for music around the world.

Letter names ain't "somewhat arbitrary", they are fully arbitrary. They do have a history, that could be mentioned somewhere. Their original purpose (and their main one until the 19th or 20th century) is to denote relative pitches, not absolute ones. The information above about the history of pitch standards is somewhat fantastic; but once again, it does not concern music theory properly speaking and should be moved to another article.

Pitch is also an important consideration in tuning systems, or temperament, used to determine the intervallic distance between tones, as within a scale. Tuning systems vary widely within and between world cultures. In Western culture, there have long been several competing tuning systems, all with different qualities. Internationally, the system known as equal temperament is most commonly used today because it is considered the most satisfactory compromise that allows instruments of fixed tuning (e.g. the piano) to sound acceptably in tune in all keys.

Temperaments concern only the instruments of fixed sounds and, as such, belong to Western music exclusively (and to its mundialization). Equal temperament is certainly not "most commonly used", even in Western music today: only pianos and electronic instruments come close to it.

Scales and modes edit

This section as a whole is fully confused between the notions of scale, mode [of which it says nothing] and key.

Notes can be arranged in a variety of scales and modes. Western music theory generally divides the octave into a series of twelve tones, called a chromatic scale, within which the interval between adjacent tones is called a half step or semitone. In equal temperament each semitone is equidistant from the next, but other tuning systems are also used. Selecting tones from this set of 12 and arranging them in patterns of semitones and whole tones creates other scales.[55]

It is somewhat surprizing to see Touma, a book about Arabic music, quoted as evidence for the 12-note scale in Western music. In addition, definitions of the chromatic scale and the semitone may not belong here.

The most commonly encountered scales are the seven-toned major, the harmonic minor, the melodic minor, and the natural minor. Other examples of scales are the octatonic scale and the pentatonic or five-tone scale, which is common in folk music and blues. Non-Western cultures often use scales that do not correspond with an equally divided twelve-tone division of the octave. For example, classical Ottoman, Persian, Indian and Arabic musical systems often make use of multiples of quarter tones (half the size of a semitone, as the name indicates), for instance in 'neutral' seconds (three quarter tones) or 'neutral' thirds (seven quarter tones)—they do not normally use the quarter tone itself as a direct interval.[55]

While I admit that the major scale is a common one, I only rarely encountered the harmonic, melodic or natural minor scales in actual music. It may be wiser to describe the minor scale as one with mobile degrees, as are many of the non-European scales. To say that Ottoman, Persian, Indian or Arabic scales "make use of multiples of quarter tones" is projecting a Western conception on these. [Touma may be outdated on this point.] It may be more interesting that many of these cultures, however they build their scales, nevertheless prefer melodies with seven notes in the octave.

In traditional Western notation, the scale used for a composition is usually indicated by a key signature at the beginning to designate the pitches that make up that scale. As the music progresses, the pitches used may change and introduce a different scale. Music can be transposed from one scale to another for various purposes, often to accommodate the range of a vocalist. Such transposition raises or lowers the overall pitch range, but preserves the intervallic relationships of the original scale. For example, transposition from the key of C major to D major raises all pitches of the scale of C major equally by a whole tone. Since the interval relationships remain unchanged, transposition may be unnoticed by a listener, however other qualities may change noticeably because transposition changes the relationship of the overall pitch range compared to the range of the instruments or voices that perform the music. This often affects the music's overall sound, as well as having technical implications for the performers.[56]