| Gurjaradesa/sandbox | |

|---|---|

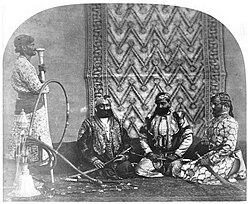

Goojar Sirdars of Rajpootana, from The People of India by Watson and Kayle. | |

| Religions | Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism, Christianity |

| Languages | Hindi, Urdu, Gujari, Punjabi, Hindko, Gujarati, Rajasthani, Pashto, Farsi, Bhojpuri, Marwari, Sindhi |

| Region | Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Jammu and Kashmir, Azad Kashmir, Bihar, Sindh, Gilgit-Baltistan, Nuristan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh, Balochistan, Delhi |

Gurjar or Gujjar (also known as Goojar, Gojar, and Guzar) is an ethnic agricultural and pastoral community of India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. The ancient name of the group was Gurjara, which is believed to have been an ethnonym in the beginning as well as a demonym later on. Gurjars are a heterogeneous group that is internally differentiated in terms of culture, religion, occupation, and socio-economic status. Historically, they have played diverse roles in society, from being rulers of several kingdoms in North India to nomads in present-day Jammu and Kashmir. At present, they are mainly a Zamindar community (local agriculture class of North India and Pakistan) and are famously known for dairy farming and cattle breeding. A relatively small number of them practice seasonal nomadism in areas that are hard to cultivate (i.e. the Himalayas and Thar Desert), and are known as Van Gujjars or Gujjar Bakarwals.

The pivotal point in the history of Gurjar identity is often traced back to the emergence of a Gurjara kingdom in present-day Rajasthan during medieval times (around 570 CE). It is believed that the Gurjars migrated to different parts of the Indian Subcontinent from the Gurjara kingdom. Previously, it was believed that the Gurjars did an earlier migration from Central Asia as well, however, that view is generally considered to be speculative. Historical references speak of Gurjara warriors and commoners in North India in the 7th century CE , and mention several Gurjara kingdoms and dynasities. The Gurjaras started fading way from the forefront of history after 10th century CE. Thereafter, several Gurjar chieftans and upstart warriors are mentioned in history, who were rather petty rulers in contrast to their predecessors. The modern forms "Gurjar" and "Gujjar" were quite common during the Mughal era, and documents dating from the period mention Gurjars as a "turbulent" people. The Indian states of Gujarat and Rajasthan were known as Gurjaradesa and Gurjaratra for centuries prior to the arrival of the British power. The Gujrat and Gujranwala districts of Pakistani Punjab have also been associated with Gujjars from as early as the 8th century CE, when there existed a Gurjara kingdom in the same area. The Saharanpur district of Uttar Pradesh was also known as Gujarat previously, due to the presence of a large number of Gujjar zamindars, or land holding farmer class, in the area.

The bulk of Gurjar population lives in the regions of Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Kashmir, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Gilgit-Baltistan, and Nuristan. A good number of them still speak Gujari language (also known as Gujri and Gojri) and wear their tribal dresses, but the traditional practices of the Gujjars have been fading away with subsequent generations.

Religiously the Gurjars are a diverse group. While they are mainly Muslims and Hindus, a number of them are also Sikhs and Christians. The Deobandi movement had a significant influence from the Gujjars of Deoband, situated in Saharanpur district (previously known as Gujarat, due to the prevalence of Gujjar population there). The child stories of Krishna are believed to have originated from the Gujjars as well.

Etymology edit

The word Gurjar represents a modern caste group in India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, locally referred to as jati, zaat, qaum or biradari [1][2] The history of the word Gurjar can be confidently traced back to an ancient ethnic and tribal identity called Gurjara, which became prominent after the collapse of Gupta Empire. A literal or definitive meaning of the word Gurjara is not available in any of the historical references. The oldest reference to the word Gurjara is found in the book called Harshacharita (Harsha's Deeds), a biography of king Harshavardhana written around 630 CE.[3] Banabhatta, the author of Harshacharita, mentions that Harsha's father Prabhakravardhana (560-580 CE) was "a constant threat to the sleep of Gurjara"—apparently a reference to the Gurjara king or kingdom. Inscriptions from a collateral branch of Gurjaras, known as Gurjaras of Lata, claim that their family was ruling Bharakucha (Bharuch) as early as 450 CE from their capital at Nandipuri. Based on these early dates, it has been proposed by some authors that Gurjara identity might have been present in India as early as the 3rd century CE, but it became prominent only after the fall of Guptas.

It has been suggested by several historians that Gurjara was initially the name of a tribe or clan which later evolved into a geographical and ethnic identity following the establishment of a janapada (tribal kingdom) called 'Gurjara'.[4] This understanding has introduced an element of ambiguity regarding ancient royal designations containing the word 'gurjara' such as 'gurjaraeshvara' or 'gurjararaja', as now its debatable whether the kings bearing these epithets were tribal or ethnic Gurjaras.[5][6]

The word 'Gurjara' is often traced by historians from groups that invaded India in early medieval times, such as Khazars also known as Guzars, or Kushans also known as Gaussuras.[7] Recently Javed Rahi has suggested that 'Gujjar' is the same word as Turkish 'Guchar' (nomad), and that Gurjar or Gurjara are its Sanskritized forms. However, Indian historians, especially of a nationalistic orientation, criticize such theories for their reliance on phonological similarities and guesswork—they argue that there is nothing in the historical records to suggest that Gurjaras had a foreign origin, as even the earliest members of this group were steeped in Indian religion and culture.

Origins edit

Theories of Indian descent edit

The historical records of ancient Gurjaras depict themselves as aboriginals of India. This is held as tantamount evidence by several historians to say that ancient Gurjaras originated from India. It is suggested that Gurjaras were probably an obscured Kshatriya tribe living somewhere in medieval Rajasthan, and following the fall of Gupta empire, they rose to prominence. According to Baij Nath Puri, the original homeland of the Gurjaras was somewhere near Mt Abu, from where they traveled to other places like Bhinmal and the rest of India. Puri agrees with F.E. Pargiter who suggests that Gurjaras could be the descendants of Guruśvaras, who are mentioned in Mārkandeya Purāna in the list of countries and races of Western India.[8] Although he admits that without any conclusive evidence, it is best to stick to what we know, that Gurjaras were a group of castes, clans and tribes centered around Mt. Abu which conquered a considerable territory in Rajasthan around 6th century CE --- he along with several other historians refers to this group as the 'Gurjara stock'.

The author C.V. Vaidya was one of the earliest to argue that Gurjaras were Kshatriyas of the Aryavarta (ancient name for India). Others such as D.C. Ganguly and K.M. Munshi also supported the views of Vaidya.

The Indian linguist Pandit Radhakant Deo believed the word Gurjara to be a Sanskrit compound of 'Guran' (enemy) and 'ujara' (destroyer). The word 'guran' is synonomous with the persian 'giran', which is also used in Urdu, to point out something 'unpleasant thing'. While the word 'ujara' is still widely used in the contemporary Indian languages such as Hindi and Urdu, carrying the meaning of 'destruction'. The fact that Gurjara kingdom was called Gurjaratra (from "Gurjara" and "tra", meaning "land protected by Gurjaras"), also indicates that Gurjara was one of the "frontier" tribes that probably gained fame from protecting their land by defeating a strong enemy.

Theories of foreign descent edit

D.R. Bhandarkar was one of the earliest authors to present a theory on the origins of ancient Gurjaras. He argued that since Gurjaras came to prominence following Huna (White Hun) invasions, they must have been an allied group of the Central Asian invaders. According to him, the Khazars of Central Asia were known as Guzar, who might have come to India alongside the White Huns. He traces their migration from Georgia which was known as Gurjia or Gurjistan in ancient times. His opinions are supported by authors such as J. Campbell, A.M.T. Jackson, Rudolf Hoernele, V.A. Smith, and R.S. Tripathi. He also mentions that names like Gurj, Gurji, and Ajjar are common in Georgia (an area which formed part of the Khazaria, or Khazar Empire).Professor Georgi Chogoshvili, belonging to the Georgian Academy of Science, has also remarked that there is a strong resemblance between the Gujjars and the Georgians.[9] V.A. Smith cites further evidence for this hypothesis. He argues that degraded coins of the Sassanian empire, called Gadhaiya coins, were found circulating in Gurjara domains around the same time, which in his opinion, give further credence to this theory.

There is nothing in the historical records to suggest that Gurjaras were looked upon as outsiders in India, either by themselves or by others. If the Gurjaras were foreign invaders it would have been apparent from the historical records, but there is no record of them being mentioned as such. The tendency to define Gurjaras, and other influential groups of India, as foreigners is often attributed a colonial mentality. The British had an agenda to look for historical parallels concerning foreign rule in India, so they could justify their own rule over Indians with impunity, saying that foreign rule is a constitutional part of India. Following the same argument, the authors which agree with theories of foreign invasions (such as Aryan Invasion) are deemed victims of the British colonial agenda.

General Alexander Cunningham believed that Gurjaras came to India from Central Asia, and traced their identity from the Kushan kings of Yuezhi confederation. He argues that the Rabatak inscription of Kushan king Kanishka mentions him as a scion of Gausura (noble) family. According to him, the word Gausura is the origin of the word Gurjara. He further argues that since Kasana is the biggest and oldest clan among Gujjars, it is further evidence that connects them with the Kushans and Yuezhis of Central-Asia.

Javed Rahi, a Gujjar himself, has presented the idea that Gujjars are the same as Göçer Turkmen (pronounced "Guchar Turkman"). He mentions the fact that Turk is an important clan of the Gujjars, and that Gujjars have similar physical features, tribal dresses, and lifestyle as the Göçer Turkmens. The word Göçer has several other forms of spellings as well, such as Kuchar. The word seems to be related to the Persian word "Kooch" (to roam, or travel).

The Kushanas were also known as Kuchi (Yuezhi/Yuchi) and one of their most important kingdoms was called Kuchar. Huen Tsang, the Chinese pilgrim which visited North India in medieval times, also mentioned the Gurjara kingdom as "Kuchilo". One of the big districts of Gujarat state is called Kachh (Kutch) as well. The similarities between the words Gujjar, Kuchar, and Kooch, could very well be just coincidences, but the fact that they are often repeated in several regions and people, may point to some actual connection.

History edit

The history of Gujjar identity is closely linked with the evolution of the word Gurjara. It is believed that Gurjara was originally the name of a warrior group which established its kingdom in Rajasthan, which was called Gurjaradesa at the time. After this region became associated with the word Gurjara for a significant amount of time, it gave rise to an ethnic identity based on the common regional, lingual, and cultural bonds between this region's inhabitants, which belonged to different castes, clans, and tribes -- several authors refer to this later Gurjara ethnic group as "Gurjara stock". The modern Gurjar or Gujjar identity has descended from the ancient Gurjara stock and is part of that groups history.

The history of Gurjar identity is closely related to a medieval people called Gurjaras, whose origins are obscured in antiquity. The Gurjaras are believed to have been a heterogenous group, consisting of several castes, clans, and tribes inhabiting the regions of Southern Rajasthan and Northern Gujarat during medieval times. These people were collectively known as Gurjaras, and their kingdom was variously called Gurjara, Gurjaradesa, Gurjarabhumi, Gurjaratra, Gurjaradhara, etc.

The word Gurjara can be traced to the sixth century CE with confidence, when it was first mentioned in the book called Harshacharita (biography of Indian emperor Harsha Vardhana). In the historical records, the term Gurjara is mostly interpreted as a tribal or geographical name, and in a comparatively few cases it may be especially taken as a tribal or personal epithet.[10] It is also known that at that time in history, janapada names (names of tribal kingdoms) were often interchangeable with tribal epithets.

Documents from the seventh century suggest a wide distribution of the Gurjaras as a political power in western India. References to Gurjara commoners may indicate that the political dominance of certain families reflected a process of stratification that had developed within the stock.[11] It is believed that the Gurjaras were originally a pastoral people, but were among the early adopters of an agrarian lifestyle. With the introduction of better irrigation models their society moved away from their nomadic heritage and towards an agricultural mode of life.

Some of the most important ruling families of the time were collectively known as Gurjaras. There is disagreement over the interpretation of the word Gurjara — whether it was an ethnonym or a demonym. However, as far as Gurjar history is concerned, that is a secondary issue. Gurjars are simply the modern representatives of all the earlier people known as Gurjaras, whose inner identity dimensions might have very well been complex.

Gurjara kingdom (565 CE - 800 CE) edit

It is believed that the fall of Gupta Empire created a political vaccum in Northern India which gave prominence to several previously obscured warrior groups, of which "Gurjaras" were one of the most important. The Gurjara rulers of Lata (Braoch/Nandipuri) state in their royal inscriptions that "Gurjara-nrpati-vamsa" (Gurjara-royal-lineage) was one the most renowned and numerous Kshatriya (warrior) lineages of Aryavarta (India).

The earliest references to the word Gurjara in history are closely linked to a medieval North Indian kingdom called Gurjaradesa, or simply Gurjara. It is believed that an obscured warrior group called Gurjara conquered the land between Mt. Abu and Bhinmal, and superimposed its name on that territory. The original Gurjara kingdom is thought to have encompassed southern-Rajasthan and northern-Gujarat.

Several historians have argued that the establishment of

Later the name Gurjara, or various forms derived from it, such as Gurjarabhumi, Gurjaramandala, Gurjaratra, and Gurjaradara, were applied to various other tracts of land in Northern India by people who also called themselves Gurjaras.

Gurjaradēśa, or Gurjara country, is first attested in Bana's Harshacharita (7th century CE). It's said that Harsha's father Prabhakaravardhana (died c. 605 CE), was a "troubler to the sleep of Gurjara", i.e. he was a constant threat to the Gurjara king or kingdom. The historical records bracket Gurjara with Sindha (Sindh), Lāta (southern Gujarat) and Malava (western Malwa) kingdoms, which indicates that the region of northern-Gujarat and Rajasthan is meant.

Huen Tsang mentions a Gurjara kingdom (Kiu-che-lo) with its capital at Bhinmal (Pi-lo-mo-lo) as the second largest kingdom of Western India — measuring 833 miles in circuit. He distinguished it from the neighbouring kingdoms of Bharukaccha (Bharuch), Ujjayini (Ujjain), Malava (Malwa), Valabhi and Surashtra. He described the Gurjara ruler as a 20-year old Kshatriya who was distinguished for his wisdom and courage. It is known from contemporary records, that around 628 CE, the kingdom at Bhinmal was ruled by a king from Chapa dynasty named Vyāgrahamukha. The mathematician-astronomer Brahmagupta, the first person to compute with zero, is known to have written his treatise under the same king. It is believed that the young ruler mentioned by Hieun Tsang must have been Vyāgrahamukha's immediate successor. Gurjara or Gurjaradesa is believed to have become independent following the death of Harsha.

The rise of the Gurjara kingdom is credited to the families of Harichandra and Naghbhatta I, both of whom belonged to the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty.

Imperial Gurjara dynasties (800 CE - 1100 CE) edit

The 9th and 10th centuries saw the rise of Gurjaras to imperial heights. Who in this era were lead by the Gurjara-Pratihara, Paramara, and Chalukya dynasties. Among them, Gurjara-Pratiharas proved to be the most ambitious and successful — they managed to conquer most of North India at one point. The contemporary records referred to these dynasties as Gurjaras, although in some cases, these clans predate the Gurjara identity. This, a few historians argue, indicates that Gurjara was a broad group, which was composed of different tribes and castes.

Historians have also suggested that Gurjara was an ethnic and cultural identity, as well as a tribal one. The secondary meanings originated from the fact that a considerable ethnic and geographical zone was known as Gurjaradesa — due to the Gurjara tribe's historic dominance over that area. People belonging to this zone were identified as Gurjaras, due to their affiliation with Gurjaradesa (i.e. Gurjara-country, or, Country-of-Gurjaras), even if they were not really part of the Gurjara tribe. Therefore, the aforementioned dynasties could very well have been Gurjaras in the secondary sense — members of a Gurjara ethnic or geographical identity — rather than the strict primary sense — members of a Gurjara tribe.

The first imperial ruler of the Gurjaras is believed to be Naghabhatta I of the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty. He is credited with pushing back the strong Arab army which had managed to consolidate its hold on Sindh. He established his leadership over Gurjaras and tried to take over Kanauj — the capital of India — which he might have brought under his control for a short period. The imperial dynasties, referred to as Gurjaras in ancient records, were each other's successors. This implies that Gurjaras contended for leadership at regular intervals within the group.

Arab and Afghan era (1100 CE - 1400 CE) edit

The Gurjara political power, which rose to imperial heights under the leadership of Gurjara-Pratiharas, began to erode at the hands of Mahmud Ghazni. It was further weakened by the cataclysmic raids of Aibak, and by the time of Alauddin Khalji conquered Delhi, the Gurjara warriors were completely subdued to the status of petty chiefs.

It is around the same time it is believed these warriors started branching off from their Gurjara identity, and got merged into the Rajaputra or Rajput identity. Hence the kingdoms of Pratiharas, Parmaras, Chauhans, Solankis, and others, dynasties which were previously known as Gurjaras, were henceforth referred to as Rajputs.

Mughal (Turkic) era (1400 CE - 1600 CE) edit

The Gurjars and the Jats of Agra stood together at the time of Surajmal Jat. After his murder, his fourth son Ranjit Singh and the Gurjar chief Motiram Baisla of Sundraoli signed a pact of treaty. As Surajmal had taken the lead on his son Motiram Baisla became the army chief of Bharatpur. In 1803 CE, after a stubborn fight, the Gujjars and Jats were defeated and thus, Bharatpur district remained as a small territory under the British rulers.

A great body of Bhati Gurjars along with Dave and Kala Gujjar settled south of Delhi on both sides of Yamuna River with their head quarter at Kasna. The Bhati Gurjar occupied 360 villages. In 1540 CE Sher Shah felt the power of Gurjars round about Delhi and they took vigorous proceeding against them. Akbar allowed these unruly Gurjars to settle IT the area. After the death Aurangzeb, the Maratha hordes of the south plundered the north and the Gurjars again took on arms. Another Bhati Gurjar chief namely Rao Amra had ousted the unruly chief of Bhurta clan and established himself as Raja at Dadri. His successor Raja Roshan Singh was ruling when the British occupied the area.

Gazi Khan Baloch founded a city Dera Gazi Khan after his name near about 1710 CE. Gazi Khan Baloch was appointed as the administrator and he proved himself as a great administrator. Mahmood Khatana with his Gurjar military personals crossed the river Indus and brought the whole area comprising the districts of Mujjafargarh and Faislabad under his total control. He constructed a fort at Dera Gazi Khan. The British annexed Gurjar Ghar to Gwalior and some portions of its area amalgamated to districts of Bhind, Murena and Dholpur and a portion to the district Agra of Uttar Pradesh. Every Gurjar in Gurjar Ghar holds its own territory. The ancestors of the Gujjars in Maharashtra had been destroted and that is why they migrated to the south. The rulers of Samshergarh were actually a sub-caste of the Gujjars. They belonged to the Khatana sub-caste.

But unfortunately, most of these states and the powers of the Gujjars were finished by the British rulers.

British era (1600 CE - 1947 CE) edit

The relationship of the Gujjars with the East India Company was not an easy one. The Gujjars were known for their fierce independence due to their semi-pastoral manners, and the British administration was habitual in forcing peasantry on its subjects to generate revenue — by making them loyal tax payers. The British motive to transform semi-pastoral people, into settled taxpayers, was seen as a threat to their lifestyle by Gujjars. They held deep detestation towards such British policies and their implementation, which often left them at a great social disadvantage. A fact which surfaced to the ground in all its glory at first in 1824 — during the Gujjar rebellion of Saharanpur — and later during the Mutiny of 1857.

Gujjars were one of the first people to rise up in arms at signs of British weakness. In the Saharanpur district, the Gujjars grew quite restless and made a last ditch effort to drive out the British, but the latter were able to contain the effort with the help of the Gurkhas of Nepal. During the course of the mutiny, almost all Gujjar villages from Meerut to Delhi revolted against the British rule. Between the rivers Jamuna and Ganga, away from the GT Road — at Dadri, Sarsawa, Deoband, Bijnour, Moradabad and Rohilkhand — Gujjar turbulence was so intense that it seemed the company’s rule had ended. According to one estimate more than a million Gujjars participated in the revolt. The participation of these pastoral and nomadic communities made the rebellion a truly people’s revolt.

As a result of their active participation in the mutiny, Gujjars were classified among the turbulent members of the Martial Races, and a number of punitive measures were taken against them. Foremost among these actions was the inclusion of Gujjars among the criminal tribes, under the Criminal Tribes Act. The Gujjars henceforth were denied employment in any government role and discriminated wherever possible. This degraded the status of Gujjars in society, as they increasingly became dependent on the goodwill of the favored groups, which were either indifferent or loyal to British rule. The Criminal Tribes Act was abolished in 1952, when the groups it was set to punish were finally declared Denotified Tribes in India. However, the old practices of discrimination against these people were soon replaced by newer ones, and the fight for equal rights for these people still continues to this day.

The Gujjar will for independence was also demonstrated in politics, two of the great political activists for Indian and Pakistani freedom were Gujjars — Chaudhry Rehmat Ali and Sardar Vallabhai Patel.

Chaudhary Rehmat Ali was the man who authored Pakistan Declaration — a pamphlet titled "Now or Never; Are We to Live or Perish Forever? — in which he coined the word Pakstan for the very first time. He derived this name from the "the five northern units of India viz., Punjab, Afghania, Kashmir, Sind and Baluchistan". By the end of 1933, the word "Pakistan" had become common vocabulary where an “I” was added to ease pronunciation (as in Afghan-i-stan). In a subsequent book Rehmat Ali discussed the etymology in further detail. "Pakistan' is both a Persian and an Urdu word. It is composed of letters taken from the names of all our South Asia homelands; that is, Punjab, Afghania, Kashmir, Sindh and Balochistan. It means the land of the Pure".

India and Pakistan (1947 CE - Present) edit

When the new nation states of India and Pakistan came to being, they inherited British governance, law, and educational system, which included discriminatory measures against the Gujjars. Therefore, the dawn of independence for the Gujjars carried a hue of past animosities as well.

Culture edit

The many mandirs and forts constructed my gujjars. the influences of "gojri" on many languages. the dresses of gujjars. the diversification of gujjar culture with a tinge of their original culture.

adsada

adasd

adsad

adsad

Demographics edit

Gujars are found in every part of North West India, from the Indus to the Ganges, and from Hazara mountains to the Peninsula. They are specially numerous along the banks of the Upper Jumna near Jagadhri and Buriya, and in the Saharanpur District which during the 18th century, was actually called Gujarat. To the east they occupied the petty state of Samptar in Bundelkhand, and one of the northern districts of Gwalior which was called Gujargar in the past. They are found scattered throughout eastern Rajputana and Gwalior, but they are more numerous in the western states especially towards Gujarat.

In southern Punjab they are thinly scattered but their number increase rapidly towards the north where they have given their names to several places, such as Gujranwala in the Rechna Doab, Gujarat in the Chaj Doab, and Gujar Khan in the Sindh Sagar Doab. They are numerous about Jhelum and Hassan Abdal, and through-out the Hazara Districts of Chitral, Kohli, and Palas, to the east of the Indus and in the contiguous districts to the west of the river.

It appears from the distribution of the Gujars that they are very prominent in Gujarat (Punjab), forming 15% of the population, Hazara, Hoshiarpur, Kashmir, Jammu, Ludhiana, Rawalpindi, Gurgaon, and Karnal where they number 20,000 or more. In the United Provinces they are prominent in Muzaffarnagar, Saharanpur, Meerut, and Bulandsahr ; and so also in Malwa, Dholpur, Indore; Jaipur, Hoshangabad, Kotah and Naimar (Narbada) and Cutch.

Side Article edit

The name Gujjar is a modern variation of the ancient name Gurjara. They are two names for essentially the same people. The history of the Gurjaras was forgotten until it was re-discovered during the 19th century, because of the archaeological surveys done under the British Raj. It was found that Gurjaras were the most prominent people in Indian history during the medieval times (460 CE - 1300 CE). This discovery posed a serious challenge to the traditional narrative of Indian history, which said that the medieval dynasties of India were known as Rajputs. The new findings about the Gurjara history created a rift between historians that has still not settled to this day.

In addition to that, when the European historians found about the numerous people called Gurjars or Gujjars, things got even more complicated for them. In a desperate bid to make sense of the present situation --- where Rajputs were living in palaces built by their Gurjara ancestors, and Gujjars or Gurjars were living among the common agricultural folk --- they came up with an elaborate theory to explain this dichotomy. They proposed that Gurjaras were foreign nomadic warriors which had come to India as invaders alongside the Huns (around 300 AD). When these Gurjara invaders became Hinduized, the prominent clans became Rajputs, while the rank and file continued being called Gurjars or Gujjars. A mythical tradition called Agnikula legend was proposed as the scene of "propagation" where these Mleech (barbarian) Gurjaras became Aryas (civilized) in the shape of Rajput Kshatriyas! However, the Agnikula legend does not even mention the word Rajput, let alone suggest anything of the sort that this theory professed! Needless to say, the theory was rejected as mere conjecture by most historians, as it was shown to have no basis in reality.

Which brings us back to the same problem, why were some of the most prominent Rajput families known as Gurjaras or Gujjars in the past? But before we can answer that question, first we have to understand who the ancient Gurjaras were.

Who were the ancient Gurjaras? edit

The origins of the Gurjaras are obscured, however, their history can be traced back to the 5th century CE with certainty.The early Gurjaras proclaimed to be Kshatriyas (Warriors) of the Arya (Noble) lineage, and were devout worshipers of Surya (Sun god). They emerged in Indian history during the medieval times as either a tribal or geographical entity. Historians often think of the ancient Gurjaras as representing a diverse stock which was composed of several castes, tribes, and clans. Authors such as B.N. Puri suggest that Gurjaras were an indigenous people of India who like many others were living in obscurity until their quest for power brought them to the forefront of Indian history.

Several ancient rulers belonging to various dynasties have referred to themselves as "Gurjara kings" in their royal inscriptions. The most prominent of these were the Pratiharas, Chahamanas, Chalukyas, Tomaras, and Parmaras. The fact that rulers from seemingly unrelated dynasties referred to themselves as Gurjara kings, has influenced historians to suggest that Gurjara were a diverse people, and several dynasties belonged to this stock. They suggest that Gurjara was a broader identity, akin to an ethnic nation, which was based on a shared geographical, cultural, and linguistic heritage, rather than a mere tribal lineage or stock.

It is supposed that in the beginning Gurjara was the name of an ancient tribal people (a federation of several clans may be), which conquered a large area in modern Rajasthan that later came to be known as Gurjara kingdom. At that point in time, the term Gurjara not only signified a tribal confederation but an ethnic and geographical identity as well, i.e. the people who belonged to the Gurjara kingdom that were part of its shared heritage. This is evident from several references in ancient inscriptions where the word Gurjara has been applied to kings, priests, farmers, and carpenters. These references indicate that the word Gurjara or Gurjar was not class bound and was equally applied to several varnas or castes, and hence, it must have been a broader identity as it is hard to imagine that a single tribe was spread over all four varnas.

Having understood that there were several inner dimensions to the identity of ancient Gurjaras, we are better equipped to understand the defining characteristics of the Gujjars, which in every sense are the living progeny of ancient Gurjaras. However, Gujjars are not the only descendants of ancient Gurjaras. Rather, Gujjars are the only descendants of Gurjaras which still refer to themselves with their ancient ethnic identity, even though members from other communities have also descended from these ancient Gurjaras, such as some of the Rajput clans.

What is the relationship between ancient Gurjaras and Rajputs? edit

References edit

- ^ Gloria Goodwin Raheja (15 September 1988). The Poison in the Gift: Ritual, Prestation, and the Dominant Caste in a North Indian Village. University of Chicago Press. pp. 01–03. ISBN 978-0-226-70729-7.

This regional dominance and the kingship (rajya) exercised by Gujar chiefs still figure prominently in oral traditions current among Saharanpur Gujars and in the depiction of their identity as Ksatriya "kings" in printed histories of the Gujar Jati.

- ^ Muhammad Asghar (2016). The Sacred and the Secular: Aesthetics in Domestic Spaces of Pakistan/Punjab. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-643-90836-0.

The main grouping is the biradari, which is a very old established norm of people identifying themselves... A larger and also ancient form of grouping is the caste (qaum). The three main ones are Jaats (farmers), Arains (who traditionally were gardeners) and Gujjars (people who tend livestock and sell milk).

- ^ Puri 1986, p. 9.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya, Brajadulal (1994). The Making of Early Medieval India. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-563415-0.

- ^ Sharma, Sanjay (2006). "Negotiating Identity and Status". Studies in History. 22 (2): 181–220. doi:10.1177/025764300602200202. ISSN 0257-6430. S2CID 144128358.

- ^ Sharma, Shanta Rani (2012). "Exploding the Myth of the Gūjara Identity of the Imperial Pratihāras". Indian Historical Review. 39 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1177/0376983612449525. ISSN 0376-9836. S2CID 145175448.

- ^ Singh, David Emmanuel. (2012). Islamization in Modern South Asia : Deobandi Reform and the Gujjar Response. Boston: De Gruyter. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-61451-185-4. OCLC 843634988.

- ^ Puri 1957, p. 4.

- ^ Sharma, Kamal Prashad; Sethi, Surinder Mohan (1997). Costumes and Ornaments of Chamba. Indus Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 9788173870675.

A study of the Gujjars in 1971 A.D. by Prof. Georgi Chogoshvili of the Georgian Academy of Science, pointed out striking similarities between the Georgians and Gujjars.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Puri 1957, p. 6.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1994, p. 64. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChattopadhyaya1994 (help)

Bibliography edit

- Puri, Baij Nath (1986). The history of the Gurjara-Pratihāras. Munshiram Manoharlal.

- Chattopadhyaya, Brajadulal (1994). The Making of Early Medieval India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-563415-0.