Western culture, sometimes equated with Western civilization, Occidental culture, the Western world, Western society, and European civilization, is the heritage of social norms, ethical values, traditional customs, belief systems, political systems, artifacts and technologies that originated in or are associated with Europe. The term also applies beyond Europe to countries and cultures whose histories are strongly connected to Europe by immigration, colonization, or influence. For example, Western culture includes countries in the Americas and Australasia, whose language and demographic ethnicity majorities are of European descent. Western culture is most strongly influenced by the Judeo-Christian and Greco-Roman cultures.[4]

Ancient Greece is considered the birthplace of many elements of Western culture, including the development of a democratic system of government and major advances in philosophy, science and mathematics. The expansion of Greek culture into the Hellenistic world of the eastern Mediterranean led to a synthesis between Greek and Near-Eastern cultures,[5] and major advances in literature, engineering, and science, and provided the culture for the expansion of early Christianity and the Greek New Testament.[6][7][8] This period overlapped with and was followed by Rome, which made key contributions in law, government, engineering and political organization.[9] The concept of a "West" dates back to the Roman Empire, where there was a cultural divide between the Greek East and Latin West, a divide that later continued in Medieval Europe between the Catholic Latin Church west and the "Greek" Eastern Orthodox east.

Western culture is characterized by a host of artistic, philosophic, literary and legal themes and traditions. Christianity, including the Roman Catholic Church,[10][11][12] Protestantism[13][14] the Eastern Orthodox Church, and Oriental Orthodoxy,[15][16] has played a prominent role in the shaping of Western civilization since at least the 4th century,[17][18][19][20][21] as did Judaism.[22][23][24][25] A cornerstone of Western thought, beginning in ancient Greece and continuing through the Middle Ages and Renaissance, is the idea of rationalism in various spheres of life developed by Hellenistic philosophy, scholasticism and humanism. The Catholic Church was for centuries at the center of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws and institutions which constitute Western civilization.[26][27] Empiricism later gave rise to the scientific method, the scientific revolution, and the Age of Enlightenment.

Western culture continued to develop with the Christianisation of Europe during the Middle Ages, the reforms triggered by the Renaissance of the 12th century and 13th century under the influence of the Islamic world via Al-Andalus and Sicily (including the transfer of technology from the East, and Latin translations of Arabic texts on science and philosophy),[28][29][30] and the Italian Renaissance as Greek scholars fleeing the fall of the Byzantine Empire brought classical traditions and philosophy.[31] Medieval Christianity is credited with creating the modern university,[32][33] the modern hospital system,[34] scientific economics,[35][27] and natural law (which would later influence the creation of international law).[36] Christianity played a role in ending practices common among pagan societies, such as human sacrifice, slavery,[37] infanticide and polygamy.[38] The globalization by successive European colonial empires spread European ways of life and European educational methods around the world between the 16th and 20th centuries.[citation needed] European culture developed with a complex range of philosophy, medieval scholasticism, mysticism and Christian and secular humanism.[39][page needed] Rational thinking developed through a long age of change and formation, with the experiments of the Enlightenment and breakthroughs in the sciences. Tendencies that have come to define modern Western societies include the concept of political pluralism, individualism, prominent subcultures or countercultures (such as New Age movements) and increasing cultural syncretism resulting from globalization and human migration.

Terminology edit

The West as a geographical area is unclear and undefined. More often a country's ideology is what will be used to categorize it as a Western society. There is some disagreement about what nations should or should not be included in the category and at what times. Many parts of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire are considered Western today but were considered Eastern in the past. However, in the past it was also the Eastern Roman Empire that had many features now seen as "Western," preserving Roman law, which was first codified by Justinian in the east,[41] as well as the traditions of scholarship around Plato, Aristotle, and Euclid that were later introduced to Italy during the Renaissance by Greek scholars fleeing the fall of Constantinople.[31] Thus, the culture identified with East and West itself interchanges with time and place (from the ancient world to the modern). Geographically, the "West" of today would include Europe (especially the states that collectively form the European Union) together with extra-European territories belonging to the English-speaking world, the Hispanidad, the Lusosphere; and the Francophonie in the wider context. Since the context is highly biased and context-dependent, there is no agreed definition what the "West" is.

It is difficult to determine which individuals fit into which category and the East–West contrast is sometimes criticized as relativistic and arbitrary.[42][43][44][page needed] Globalism has spread Western ideas so widely that almost all modern cultures are, to some extent, influenced by aspects of Western culture. Stereotyped views of "the West" have been labeled Occidentalism, paralleling Orientalism—the term for the 19th-century stereotyped views of "the East".

As Europeans discovered the wider world, old concepts adapted. The area that had formerly been considered the Orient ("the East") became the Near East as the interests of the European powers interfered with Meiji Japan and Qing China for the first time in the 19th century.[45] Thus the Sino-Japanese War in 1894–1895 occurred in the Far East while the troubles surrounding the decline of the Ottoman Empire simultaneously occurred in the Near East.[a] The term Middle East in the mid-19th century included the territory east of the Ottoman Empire, but West of China—Greater Persia and Greater India—is now used synonymously with "Near East" in most languages.

History edit

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

The earliest civilizations which influenced the development of Western culture were those of Mesopotamia; the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran: the cradle of civilization.[46][47] Ancient Egypt similarly had a strong influence on Western culture.

The Greeks contrasted themselves with both their Eastern neighbours (such as the Trojans in Iliad) as well as their Western neighbours (who they considered barbarians).[citation needed] Concepts of what is the West arose out of legacies of the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire. Later, ideas of the West were formed by the concepts of Latin Christendom and the Holy Roman Empire. What is thought of as Western thought today originates primarily from Greco-Roman and Germanic influences, and includes the ideals of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment, as well as Christian culture.

Classical West edit

While the concept of a "West" did not exist until the emergence of the Roman Republic, the roots of the concept can be traced back to Ancient Greece. Since Homeric literature (the Trojan Wars), through the accounts of the Persian Wars of Greeks against Persians by Herodotus, and right up until the time of Alexander the Great, there was a paradigm of a contrast between Greeks and other civilizations. Greeks felt they were the most civilized and saw themselves (in the formulation of Aristotle) as something between the advanced civilisations of the Near East (who they viewed as soft and slavish) and the wild barbarians of most of Europe to the west.

Alexander's conquests led to the emergence of a Hellenistic civilization, representing a synthesis of Greek and Near-Eastern cultures in the Eastern Mediterranean region.[5] The Near-Eastern civilizations of Ancient Egypt and the Levant, which came under Greek rule, became part of the Hellenistic world. The most important Hellenistic centre of learning was Ptolemaic Egypt, which attracted Greek, Egyptian, Jewish, Persian, Phoenician and even Indian scholars.[48] Hellenistic science, philosophy, architecture, literature and art later provided a foundation embraced and built upon by the Roman Empire as it swept up Europe and the Mediterranean world, including the Hellenistic world in its conquests in the 1st century BCE.

Following the Roman conquest of the Hellenistic world, the concept of a "West" arose, as there was a cultural divide between the Greek East and Latin West. The Latin-speaking Western Roman Empire consisted of Western Europe and Northwest Africa, while the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire (later the Byzantine Empire) consisted of the Balkans, Asia Minor, Egypt and Levant. The "Greek" East was generally wealthier and more advanced than the "Latin" West[citation needed]. With the exception of Italia, the wealthiest provinces of the Roman Empire were in the East, particularly Roman Egypt which was the wealthiest Roman province outside of Italia.[49][50] Nevertheless, the Celts in the West created some significant literature in the ancient world whenever they were given the opportunity (an example being the poet Caecilius Statius), and they developed a large amount of scientific knowledge themselves (as seen in their Coligny Calendar).

For about five hundred years, the Roman Empire maintained the Greek East and consolidated a Latin West, but an East–West division remained, reflected in many cultural norms of the two areas, including language. Eventually, the empire became increasingly split into a Western and Eastern part, reviving old ideas of a contrast between an advanced East, and a rugged West. In the Roman world, one could speak of three main directions: North (Celtic tribal states and Parthians), the East (lux ex oriente), and finally the South (Quid novi ex Africa?), the latter conquered after the Punic Wars.

From the time of Alexander the Great (the Hellenistic period), Greek civilization came in contact with Jewish civilization. Christianity would eventually emerge from the syncretism of Hellenic culture, Roman culture, and Second Temple Judaism, gradually spreading across the Roman Empire and eclipsing its antecedents and influences.[51]

Medieval West edit

Heirs to Rome: Western, Orthodox, and Islamic civilizations edit

-

This page (folio 292r) of the Book of Kells contains the lavishly decorated text that opens the Gospel of John.

-

"Muhammad the Apostle of God"

inscribed on the gates of the Prophet's Mosque in Medina

From the cultural chaos left behind by the death of Classical civilization arose three civilizations: Western, Orthodox, and Islamic.[53] In a narrow sense, the Medieval West referred specifically to the Catholic "Latin" West, also called "Frankish" during Charlemagne's reign, in contrast to the Orthodox East, where Greek remained the language of the Byzantine Empire. In its broadest sense, the Medieval West refers to the whole of Christendom,[54] including both the Catholic West and the Orthodox East.

Although the Orthodox and Islamic civilizations enriched the Western world, it is Western civilization that would go on to produce the major breakthroughs that would give rise to the modern world. Europe rose during the Middle Ages as the fusion of Classical Greco-Roman, Christian, and Germanic traditions.[55] A coherent Western civilization can be defined by the time of the Middle Ages, emerging, with the most characteristic medieval achievements themselves, by the 11th and 12th centuries.[56] The rise of Christianity reshaped much of the Greco-Roman tradition and culture; the Christianised culture would be the basis for the development of Western civilization after the fall of Rome (which resulted from increasing pressure from barbarians outside Roman culture). Roman culture also mixed with Celtic, Germanic, and Slavic cultures, which slowly became integrated into Western culture: starting mainly with their acceptance of Christianity.

Early Middle Ages edit

The Germanic invaders did not seek to destroy Roman civilization but rather to share in its advantages. Theodoric the Great, the Germanic ruler of Italy, for example, retained the Roman Senate, civil services and schools. The Burgundians of Gaul and the Visigoths maintained Roman law for their conquered subjects, and the Frankish ruler Clovis wore Roman imperial colours and took Roman titles. However, most of the Germanic kingdoms proved to be torn too much by warfare, internal rebellion, and assassination to make an enduring impact-with the notable exception of the Franks.[55]

The main intermediary between classical antiquity and the following centuries was Saint Boethius. He wrote Consolation of Philosophy (De consolatione philosophiae), while in exile under house arrest or in prison while awaiting his execution under Theodoric the Great.[57] This work represented an imaginary dialogue between himself and philosophy, with philosophy personified as a woman.[57] The book argues that despite the apparent inequality of the world, there is, in Platonic fashion, a higher power and everything else is secondary to that divine Providence.[58] Several manuscripts survived and these were widely edited, translated and printed throughout the late 15th century and later in Europe.[57] Beyond Consolation of Philosophy, his lifelong project was a deliberate attempt to preserve ancient classical knowledge, particularly philosophy. Boethius intended to translate all the works of Aristotle and Plato from the original Greek into Latin.[59][60][61]

Cassiodorus was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great. He spent his career trying to bridge the 6th-century cultural divides: between East and West, Greek culture and Latin, Roman and Goth, and between an Orthodox people and their Arian rulers.

Saint Isidore of Seville is widely regarded, in the oft-quoted words of the 19th-century historian Montalembert, as "the last scholar of the ancient world."[62] He wrote Etymologiae, an etymological encyclopedia which assembled extracts of many books from classical antiquity that would have otherwise been lost.

The translations and compilations made by Boethius, Cassiodorus, and Isidore, the books copied and collected by monks and nuns, and the schools established in monasteries saved intellectual life during the Early Middle Ages.[63]

The period between 500 and 700 could also be designated the "Age of the Monk". Christian aesthetes, like St. Benedict (480–543) vowed a life of chastity, obedience and poverty, and after rigorous intellectual training and self-denial, lived by the “Rule of Benedict.” This “Rule” became the foundation of the majority of the thousands of monasteries that spread across what is modern day Europe; "...certainly there will be no demur in recognizing that St.Benedict's Rule has been one of the great facts in the history of western Europe, and that its influence and effects are with us to this day."[64]

Monasteries were models of productivity and economic resourcefulness teaching their local communities animal husbandry, cheese making, wine making and various other skills.[65] They were havens for the poor, hospitals, hospices for the dying, and schools. Medical practice was highly important in medieval monasteries, and they are best known for their contributions to medical tradition, but they also made some advances in other sciences such as astronomy.[66] For centuries, nearly all secular leaders were trained by monks simply because, excepting private tutors, it was the only education available.[67]

The formation of these organized bodies of believers distinct from political and familial authority, especially for women, gradually carved out a series of social spaces with some amount of independence thereby revolutionizing social history.[68]

In 496 the Frankish ruler Clovis converted to Roman Christianity. His conversion was an event of great significance.[69]

Later on, Charlemagne became king of the Franks, and his rule spurred the Carolingian Renaissance. According to John Contreni, the Carolingian Renaissance "had a spectacular effect on education and culture in Francia, a debatable effect on artistic endeavors, and an unmeasurable effect on what mattered most to the Carolingians, the moral regeneration of society".[70][71] The secular and ecclesiastical leaders of the Carolingian Renaissance made efforts to write better Latin, to copy and preserve patristic and classical texts, and to develop a more legible, classicizing script. (This was the Carolingian minuscule that Renaissance humanists took to be Roman and employed as humanist minuscule, from which has developed early modern Italic script.) They also applied rational ideas to social issues for the first time in centuries, providing a common language and writing style that enabled communication throughout most of Europe.

High and late Middle Ages edit

The Church founded many cathedrals, universities, monasteries and seminaries, some of which continue to exist today. Medieval Christianity is credited with creating the first modern universities.[32][33] The Catholic Church established a hospital system in Medieval Europe that vastly improved upon the Roman valetudinaria[72] and Greek healing temples.[73] These hospitals were established to cater to "particular social groups marginalized by poverty, sickness, and age," according to historian of hospitals, Guenter Risse.[34] Christianity played a role in ending practices common among pagan societies, such as human sacrifice, slavery,[37] infanticide and polygamy.[38] Francisco de Vitoria, a disciple of Thomas Aquinas and a Catholic thinker who studied the issue regarding the human rights of colonized natives, is recognized by the United Nations as a father of international law, and now also by historians of economics and democracy as a leading light for the West's democracy and rapid economic development.[74] Joseph Schumpeter, an economist of the twentieth century, referring to the Scholastics, wrote, "it is they who come nearer than does any other group to having been the 'founders' of scientific economics."[35] Other economists and historians, such as Raymond de Roover, Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson, and Alejandro Chafuen, have also made similar statements. Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford University said the Catholic Church is "at the center of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws, and institutions which constitute what we call Western civilization."[27]

In a broader sense, the Middle Ages, with its fertile encounter between Greek philosophical reasoning and Levantine monotheism was not confined to the West but also stretched into the old East. The philosophy and science of Classical Greece was largely forgotten in Europe after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, other than in isolated monastic enclaves (notably in Ireland, which had become Christian but was never conquered by Rome).[75] The learning of Classical Antiquity was better preserved in the Byzantine Eastern Roman Empire. Justinian's Corpus Juris Civilis Roman civil law code was created in the East in his capital of Constantinople,[41] and that city maintained trade and intermittent political control over outposts such as Venice in the West for centuries. Classical Greek learning was also subsumed, preserved and elaborated in the rising Eastern world, which gradually supplanted Roman-Byzantine control as a dominant cultural-political force. Thus, much of the learning of classical antiquity was slowly reintroduced to European civilization in the centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

The rediscovery of the Justinian Code in Western Europe early in the 10th century rekindled a passion for the discipline of law, which crossed many of the re-forming boundaries between East and West. In the Catholic or Frankish west, Roman law became the foundation on which all legal concepts and systems were based. Its influence is found in all Western legal systems, although in different manners and to different extents. The study of canon law, the legal system of the Catholic Church, fused with that of Roman law to form the basis of the refounding of Western legal scholarship. During the Reformation and Enlightenment, the ideas of civil rights, equality before the law, procedural justice, and democracy as the ideal form of society began to be institutionalized as principles forming the basis of modern Western culture, particularly in Protestant regions.

In the 14th century, starting from Italy and then spreading throughout Europe,[76] there was a massive artistic, architectural, scientific and philosophical revival, as a result of the Christian revival of Greek philosophy, and the long Christian medieval tradition that established the use of reason as one of the most important of human activities.[77] This period is commonly referred to as the Renaissance. In the following century, this process was further enhanced by an exodus of Greek Christian priests and scholars to Italian cities such as Venice after the end of the Byzantine Empire with the fall of Constantinople.

From Late Antiquity, through the Middle Ages, and onwards, while Eastern Europe was shaped by the Orthodox Church, Southern and Central Europe were increasingly stabilized by the Catholic Church which, as Roman imperial governance faded from view, was the only consistent force in Western Europe.[78] In 1054 came the Great Schism that, following the Greek East and Latin West divide, separated Europe into religious and cultural regions present to this day. Until the Age of Enlightenment,[79] Christian culture took over as the predominant force in Western civilization, guiding the course of philosophy, art, and science for many years.[78][80] Movements in art and philosophy, such as the Humanist movement of the Renaissance and the Scholastic movement of the High Middle Ages, were motivated by a drive to connect Catholicism with Greek and Arab thought imported by Christian pilgrims.[81][82][83] However, due to the division in Western Christianity caused by the Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment, religious influence—especially the temporal power of the Pope—began to wane.[84][85]

From the late 15th century to the 17th century, Western culture began to spread to other parts of the world through explorers and missionaries during the Age of Discovery, and by imperialists from the 17th century to the early 20th century. During the Great Divergence, a term coined by Samuel Huntington[86] the Western world overcame pre-modern growth constraints and emerged during the 19th century as the most powerful and wealthy world civilization of the time, eclipsing Qing China, Mughal India, Tokugawa Japan, and the Ottoman Empire. The process was accompanied and reinforced by the Age of Discovery and continued into the modern period. Scholars have proposed a wide variety of theories to explain why the Great Divergence happened, including lack of government intervention, geography, colonialism, and customary traditions.

Modern era edit

Renaissance edit

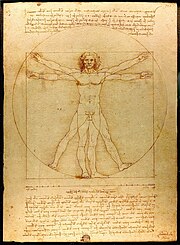

The Renaissance was a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to Modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries.

The intellectual basis of the Renaissance was its version of humanism, derived from the concept of Roman Humanitas. Renaissance humanism also awoke in man a love of learning and "a true love for books....[where] humanists built book collections and university libraries developed." Humanists believed that the individual encompassed "body, mind, and soul" and learning was very much apart of edifying all aspect of the human. This love of and for learning would lead to a demand in the printed word, which in turn drove the invention of Gutenberg's printing press.[87]

The Renaissance saw the rise of Christian humanism. Historically, major forces shaping the development of Christian humanism was the Christian doctrine that God, in the person of Jesus, became human in order to redeem humanity, and the further injunction for the participating human collective (the church) to act out the life of Christ.[88] Many of these ideas had emerged among the patristics, and would develop into Christian humanism in the late 15th century, through which the ideals of "common humanity, universal reason, freedom, personhood, human rights, human emancipation and progress, and indeed the very notion of secularity (describing the present saeculum preserved by God until Christ’s return) are literally unthinkable without their Christian humanistic roots."[89][90][91]

Reformation edit

Rise of Sovereignty edit

From the thirteenth to the seventeenth century, a new and unique form of political organization emerged in the West: the dynastic, or national, state, which, through taxes and war, harnessed the power of its nobility and the material resources of its territory.[92]

Age of Enlightenment edit

Philosophers of the Enlightenment included Francis Bacon, René Descartes, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, Voltaire (1694–1778), David Hume, and Immanuel Kant.[93] influenced society by publishing widely read works. Upon learning about enlightened views, some rulers met with intellectuals and tried to apply their reforms, such as allowing for toleration, or accepting multiple religions, in what became known as enlightened absolutism. New ideas and beliefs spread around Europe and were fostered by an increase in literacy due to a departure from solely religious texts. Publications include Encyclopédie (1751–72) that was edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert. The Dictionnaire philosophique (Philosophical Dictionary, 1764) and Letters on the English (1733) written by Voltaire spread the ideals of the Enlightenment.

Scientific Revolution edit

Coinciding with the Age of Enlightenment was the scientific revolution, spearheaded by Newton. This included the emergence of modern science, during which developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transformed views of society and nature.[94][95][96][97][98][99] While its dates are disputed, the publication in 1543 of Nicolaus Copernicus's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) is often cited as marking the beginning of the scientific revolution, and its completion is attributed to the "grand synthesis" of Newton's 1687 Principia.

Industrial Revolution edit

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in the period from about 1760 to sometime between 1820 and 1840. This included going from hand production methods to machines, new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes, improved efficiency of water power, the increasing use of steam power, and the development of machine tools.[100] These transitions began in Great Britain, and spread to Western Europe and North America within a few decades.[101]

The Industrial Revolution marks a major turning point in history; almost every aspect of daily life was influenced in some way. In particular, average income and population began to exhibit unprecedented sustained growth. Some economists say that the major impact of the Industrial Revolution was that the standard of living for the general population began to increase consistently for the first time in history, although others have said that it did not begin to meaningfully improve until the late 19th and 20th centuries.[102][103][104] The precise start and end of the Industrial Revolution is still debated among historians, as is the pace of economic and social changes.[105][106][107][108] GDP per capita was broadly stable before the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the modern capitalist economy,[109] while the Industrial Revolution began an era of per-capita economic growth in capitalist economies.[110] Economic historians are in agreement that the onset of the Industrial Revolution is the most important event in the history of humanity since the domestication of animals, plants[111] and fire.

The First Industrial Revolution evolved into the Second Industrial Revolution in the transition years between 1840 and 1870, when technological and economic progress continued with the increasing adoption of steam transport (steam-powered railways, boats, and ships), the large-scale manufacture of machine tools and the increasing use of machinery in steam-powered factories.[112][113][114]

Age of Contradiction:Progress and Breakdown edit

World Wars and Totalitarianism edit

Contemporary Age edit

Tendencies that have come to define modern Western societies include the concept of political pluralism, individualism, prominent subcultures or countercultures (such as New Age movements) and increasing cultural syncretism resulting from globalization and human migration. Western culture has been heavily influenced by the Renaissance, the Ages of Discovery and Enlightenment and the Industrial and Scientific Revolutions.[115][116]

In the 20th century, Christianity declined in influence in many Western countries, mostly in the European Union where some member states have experienced falling church attendance and membership in recent years,[117] and also elsewhere. Secularism (separating religion from politics and science) increased. Christianity remains the dominant religion in the Western world, where 70% are Christians.[118]

The West went through a series of great cultural and social changes between 1945 and 1980. The emergent mass media (film, radio, television and recorded music) created a global culture that could ignore national frontiers. Literacy became almost universal, encouraging the growth of books, magazines and newspapers. The influence of cinema and radio remained, while televisions became near essentials in every home.

By the mid-20th century, Western culture was exported worldwide, and the development and growth of international transport and telecommunication (such as transatlantic cable and the radiotelephone) played a decisive role in modern globalization. The West has contributed a great many technological, political, philosophical, artistic and religious aspects to modern international culture: having been a crucible of Catholicism, Protestantism, democracy, industrialisation; the first major civilisation to seek to abolish slavery during the 19th century, the first to enfranchise women (beginning in Australasia at the end of the 19th century) and the first to put to use such technologies as steam, electric and nuclear power. The West invented cinema, television, the personal computer and the Internet; produced artists such as Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Rembrandt, Bach, and Mozart; developed sports such as soccer, cricket, golf, tennis, rugby and basketball; and transported humans to an astronomical object for the first time with the 1969 Apollo 11 Moon Landing.

- ^ Barbero, Alessandro (2004). Charlemagne, Father of a continent.

- ^ Perry, Marvin (2008). Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics,and Society: To 1789, Ninth Edition. pp. 217–218.

- ^ Krauskopf, I. 2006. "The Grave and Beyond." The Religion of the Etruscans. edited by N. de Grummond and E. Simon. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. vii, p. 73-75.

- ^ Marvin Perry, Myrna Chase, James Jacob, Margaret Jacob, Theodore H. Von Laue (1 January 2012). Western Civilization: Since 1400. Cengage Learning. p. XXIX. ISBN 978-1-111-83169-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Green, Peter. Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- ^ Russo, Lucio (2004). The Forgotten Revolution: How Science Was Born in 300 BC and Why It Had To Be Reborn. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-20396-6.

- ^ "Hellenistic Age". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ Green, P (2008). Alexander The Great and the Hellenistic Age. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-7538-2413-9.

- ^ Jonathan Daly (19 December 2013). The Rise of Western Power: A Comparative History of Western Civilization. A&C Black. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-1-4411-1851-6.

- ^ Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2016). Western Civilization: A Brief History, Volume I: To 1715 (Cengage Learning ed.). p. 156. ISBN 978-1-305-63347-6.

- ^ Neill, Thomas Patrick (1957). Readings in the History of Western Civilization, Volume 2 (Newman Press ed.). p. 224.

- ^ O'Collins, Gerald; Farrugia, Maria (2003). Catholicism: The Story of Catholic Christianity. Oxford University Press. p. v (preface). ISBN 978-0-19-925995-3.

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage (1956), Tübingen (Germany), pp. 317–319, 325–326

- ^ The Protestant Heritage, Britannica

- ^ McNeill, William H. (2010). History of Western Civilization: A Handbook (University of Chicago Press ed.). p. 204. ISBN 978-0-226-56162-2.

- ^ Faltin, Lucia; Melanie J. Wright (2007). The Religious Roots of Contemporary European Identity (A&C Black ed.). p. 83. ISBN 978-0-8264-9482-5.

- ^ Roman Catholicism, "Roman Catholicism, Christian church that has been the decisive spiritual force in the history of Western civilization". Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Caltron J.H Hayas, Christianity and Western Civilization (1953), Stanford University Press, p. 2: That certain distinctive features of our Western civilization—the civilization of western Europe and of America—have been shaped chiefly by Judaeo–Graeco–Christianity, Catholic and Protestant.

- ^ Jose Orlandis, 1993, "A Short History of the Catholic Church," 2nd edn. (Michael Adams, Trans.), Dublin:Four Courts Press, ISBN 1851821252, preface, see [1], accessed 8 December 2014. p. (preface)

- ^ Thomas E. Woods and Antonio Canizares, 2012, "How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization," Reprint edn., Washington, D.C.: Regnery History, ISBN 1596983280, see accessed 8 December 2014. p. 1: "Western civilization owes far more to Catholic Church than most people—Catholic included—often realize. The Church in fact built Western civilization."

- ^ Marvin Perry (1 January 2012). Western Civilization: A Brief History, Volume I: To 1789. Cengage Learning. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-1-111-83720-4.

- ^ Noble, Thomas F. X. (2013-01-01). Western civilization : beyond boundaries (7th ed.). Boston, MA. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-133-60271-2. OCLC 858610469.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Marvin Perry; Myrna Chase; James Jacob; Margaret Jacob; Jonathan W Daly (2015). Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society, Volume I: To 1789. Cengage Learning. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-305-44548-2.

- ^ Hengel, Martin (2003). Judaism and Hellenism : studies in their encounter in Palestine during the early Hellenistic period. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59244-186-0. OCLC 52605048.

- ^ Porter, Stanley E. (2013). Early Christianity in its Hellenistic context. Volume 2, Christian origins and Hellenistic Judaism : social and literary contexts for the New Testament. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004234765. OCLC 851653645.

- ^ Woods, Thomas E. (2005). How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization. Washington, DC: Regency Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89526-038-3.

- ^ a b c "Review of How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization by Thomas Woods, Jr". National Review Book Service. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ Haskins, Charles Homer (1927), The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-6747-6075-2

- ^ George Sarton: A Guide to the History of Science Waltham Mass. U.S.A. 1952

- ^ Burnett, Charles. "The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century," Science in Context, 14 (2001): 249–288.

- ^ a b Geanakoplos, Deno John. Constantinople and the West: essays on the late Byzantine (Palaeologan) and Italian Renaissances and the Byzantine and Roman churches. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

- ^ a b Rüegg, Walter: "Foreword. The University as a European Institution", in: A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. xix–xx

- ^ a b Verger 1999

- ^ a b Risse, Guenter B. (April 1999). Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-19-505523-8.

- ^ a b Schumpeter, Joseph (1954). History of Economic Analysis. London: Allen & Unwin.

- ^ Cf. Jeremy Waldron (2002), God, Locke, and Equality: Christian Foundations in Locke's Political Thought, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (UK), ISBN 978-0-521-89057-1, pp. 189, 208

- ^ a b Chadwick, Owen p. 242.

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 309.

- ^ Sailen Debnath, 2010, "Secularism: Western and Indian," New Delhi, India:Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 8126913665.[page needed]

- ^ Huntington, Samuel P. (2 August 2011). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon & Schuster. pp. 151–154. ISBN 978-1-4516-2897-5.

- ^ a b Kaiser, Wolfgang (2015). The Cambridge Companion to Roman Law. pp. 119–148.

- ^ Yin Cheong Cheng, New Paradigm for Re-engineering Education. p. 369

- ^ Ainslie Thomas Embree, Carol Gluck, Asia in Western and World History: A Guide for Teaching. p. xvi

- ^ Kwang-Sae Lee, East and West: Fusion of Horizons[page needed]

- ^ Davidson, Roderic H. (1960). "Where is the Middle East?". Foreign Affairs. 38 (4): 665–75. doi:10.2307/20029452. JSTOR 20029452. S2CID 157454140.

- ^ Jacobus Bronowski; The Ascent of Man; Angus & Robertson, 1973 ISBN 0-563-17064-6

- ^ Geoffrey Blainey; A Very Short History of the World; Penguin Books, 2004

- ^ George G. Joseph (2000). The Crest of the Peacock, p. 7-8. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00659-8.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2007), Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History, p. 55, table 1.14, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1

- ^ Hero (1899). "Pneumatika, Book ΙΙ, Chapter XI". Herons von Alexandria Druckwerke und Automatentheater (in Greek and German). Translated by Wilhelm Schmidt. Leipzig: B.G. Teubner. pp. 228–232.

- ^ Gordon, Cyrus H., The Common Background of the Greek and Hebrew Civilasations, W. W. Norton and Company, New York 1965

- ^ Fortenberry, Diane (2017). THE ART MUSEUM. Phaidon. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7148-7502-6.

- ^ Quigley, Carroll (1979). The Evolution of Civilizations. p. 333.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. The Age of Enlightenment: St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ a b Perry, Marvin (2008). Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society, Volume I: to 1789, Ninth Edition. pp. 209–210.

- ^ Stearns, Peter (2003). Western civilization in world history. p. 49.

- ^ a b c Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus. Consolation of Philosophy. Translated by Joel Relihan. Norton: Hackett Publishing Company, 2001.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

muwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Spade, Paul Vincent (15 March 2016), "Medieval Philosophy", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, retrieved 23 October 2017

- ^ Thomas Aquinas; Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt (2005), Holy Teaching: Introducing the Summa Theologiae of St. Thomas Aquinas, Brazos Press, pp. 14–, ISBN 978-1-58743-035-0, retrieved 22 March 2013

- ^ Rubenstein, Richard E. (2004). Aristotle's Children. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-0-547-35097-4. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ Montalembert, Charles F. Les Moines d'Occident depuis Saint Benoît jusqu'à Saint Bernard [The Monks of the West from Saint Benoit to Saint Bernard]. Paris: J. Lecoffre, 1860.

- ^ Perry, Marvin (2008). Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society, Volume I: to 1789, Ninth Edition. pp. 212.

- ^ Butler, Cuthbert (1919). Benedictine Monachism: Studies in Benedictine Life and Rule. New York: Longmans, Green and Company. pp. 3–8.: intro.

- ^ Dunn, Dennis J. (2016). A History of Orthodox, Islamic, and Western Christian Political Values. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 60. ISBN 978-3-319-32566-8.

- ^ Koenig, Harold G.; King, Dana E.; Carson, Verna Benner, eds. (2012). Handbook of Religion and Health (second ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-0-19-533595-8.

- ^ Monroe, Paul (1909). A Text-book in the History of Education. London, England: The Macmillan Company. p. 253.

- ^ Haight, Roger D. (2004). Christian Community in History Volume 1: Historical Ecclesiology. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 273. ISBN 0-8264-1630-6.

- ^ Perry, Marvin (2008). Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society, Volume I: to 1789, Ninth Edition. pp. 215.

- ^ Contreni, John G. (1984), "The Carolingian Renaissance", Renaissances before the Renaissance: cultural revivals of late antiquity and the Middle Ages, page 59

- ^ Nelson, Janet L. (1986), "On the limits of the Carolingian renaissance", Politics and Ritual in Early Medieval Europe.

- ^ "Valetudinaria". broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Risse, Guenter B. (15 April 1999). Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974869-3.

- ^ de Torre, Fr. Joseph M. (1997). "A Philosophical and Historical Analysis of Modern Democracy, Equality, and Freedom Under the Influence of Christianity". Catholic Education Resource Center.

- ^ "How The Irish Saved Civilisation", by Thomas Cahill, 1995[page needed]

- ^ Burke, P., The European Renaissance: Centre and Peripheries (1998)

- ^ Grant God and Reason p. 9

- ^ a b Koch, Carl (1994). The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. Early Middle Ages: St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). "The Age of Enlightenment". The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). "High Middle Ages". The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). "Renaissance". The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). p. 25. ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). "Reformation". The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). "Enlightenment". The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Frank 2001.

- ^ Murray, Stuart, 1948- (2009). Library, the : an illustrated history. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. pp. 58, 68. ISBN 978-1-62873-322-8. OCLC 855503629.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Zimmerman, Jens. "Introduction," in Zimmermann, Jens, ed. Re-Envisioning Christian Humanism. Oxford University Press, 2017, 5.

- ^ Zimmermann, 6-7.

- ^ Croce, Benedetto Croce. My Philosophy and Other Essays on the Moral and Political Problems of Our Time (London: Allen & Unwin, 1949)

- ^ Zimmermann, Jens. Humanism and Religion: A Call for the Renewal of Western Culture. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- ^ Perry, Marvin (2008). Western civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society: to 1789, Ninth Edition. pp. 317-399

- ^ Sootin, Harry. "Isaac Newton." New York, Messner (1955)

- ^ Galileo Galilei, Two New Sciences, trans. Stillman Drake, (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Pr., 1974), pp. 217, 225, 296–97.

- ^ Ernest A. Moody (1951). "Galileo and Avempace: The Dynamics of the Leaning Tower Experiment (I)". Journal of the History of Ideas. 12 (2): 163–93. doi:10.2307/2707514. JSTOR 2707514.

- ^ Marshall Clagett, The Science of Mechanics in the Middle Ages, (Madison, Univ. of Wisconsin Pr., 1961), pp. 218–19, 252–55, 346, 409–16, 547, 576–78, 673–82; Anneliese Maier, "Galileo and the Scholastic Theory of Impetus," pp. 103–23 in On the Threshold of Exact Science: Selected Writings of Anneliese Maier on Late Medieval Natural Philosophy, (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Pr., 1982).

- ^ Hannam, p. 342

- ^ E. Grant, The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional, and Intellectual Contexts, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1996), pp. 29–30, 42–47.

- ^ "Scientific Revolution". Encarta. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- ^ Landes 1969, p. 40

- ^ Landes 1969

- ^ Lucas, Robert E., Jr. (2002). Lectures on Economic Growth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 109–10. ISBN 978-0-674-01601-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Feinstein, Charles (September 1998). "Pessimism Perpetuated: Real Wages and the Standard of Living in Britain during and after the Industrial Revolution". Journal of Economic History. 58 (3): 625–58. doi:10.1017/s0022050700021100.

- ^ Szreter, Simon; Mooney, Graham (February 1998). "Urbanization, Mortality, and the Standard of Living Debate: New Estimates of the Expectation of Life at Birth in Nineteenth-Century British Cities". The Economic History Review. 51 (1): 104. doi:10.1111/1468-0289.00084.

- ^ Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution: Europe 1789–1848, Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd., p. 27 ISBN 0-349-10484-0

- ^ Joseph E Inikori. Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01079-9.

- ^ Berg, Maxine; Hudson, Pat (1992). "Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution" (PDF). The Economic History Review. 45 (1): 24–50. doi:10.2307/2598327. JSTOR 2598327.

- ^ Julie Lorenzen. "Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution". Archived from the original on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- ^ Robert Lucas Jr. (2003). "The Industrial Revolution". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

it is fairly clear that up to 1800 or maybe 1750, no society had experienced sustained growth in per capita income. (Eighteenth century population growth also averaged one-third of 1 percent, the same as production growth.) That is, up to about two centuries ago, per capita incomes in all societies were stagnated at around $400 to $800 per year.

- ^ Lucas, Robert (2003). "The Industrial Revolution Past and Future". Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

[consider] annual growth rates of 2.4 percent for the first 60 years of the 20th century, of 1 percent for the entire 19th century, of one-third of 1 percent for the 18th century

- ^ McCloskey, Deidre (2004). "Review of The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain (edited by Roderick Floud and Paul Johnson), Times Higher Education Supplement, 15 January 2004".

- ^ Taylor, George Rogers (1951). The Transportation Revolution, 1815–1860. ISBN 978-0-87332-101-3. No name is given to the transition years. The "Transportation Revolution" began with improved roads in the late 18th century.

- ^ Roe, Joseph Wickham (1916), English and American Tool Builders, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, LCCN 16011753. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (LCCN 27-24075); and by Lindsay Publications, Inc., Bradley, Illinois, (ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7).

- ^ Hunter 1985

- ^ "Western culture". Science Daily.

- ^ "A brief history of Western culture". Khan Academy.

- ^ Ford, Peter (22 February 2005). "What place for God in Europe". USA Today. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ ANALYSIS (19 December 2011). "Global Christianity". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).