The term missing link refers back to the static, non-evolutionary concept of the great chain of being, a deist idea that all existence is linked, from the lowest dirt, through the living kingdoms to angels and finally to God.[1] The idea of all living things being linked through some sort of transmutation process predates Darwin's theory of evolution. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck envisioned that life is generated in the form of the simplest creatures constantly, and then strive towards complexity and perfection (i.e. humans) through a series of lower forms.[2] In his view, lower animals were simply newcomers on the evolutionary scene.[3]

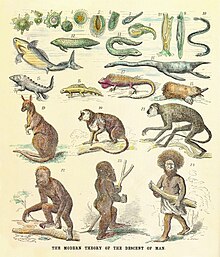

After On the Origin of Species, the idea of "lower animals" representing earlier stages in evolution lingered, as demonstrated in Ernst Haeckel's figure of the human pedigree.[4] While the vertebrates were then seen as forming a sort of evolutionary sequence, the various classes were distinct, the undiscovered intermediate forms being called "missing links".

The term was first used in a scientific context by Charles Lyell in the third edition (1851) of his book Elements of Geology in relation to missing parts of the geological column, but it was popularized in its present meaning by its appearance on page xi of his book Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man of 1863. By that time it was generally thought that the end of the last glacial period marked the first appearance of humanity, but Lyell drew on new findings in his Antiquity of Man to put the origin of human beings much further back in the deep geological past. Lyell wrote that it remained a profound mystery how the huge gulf between man and beast could be bridged.[5] Lyell's vivid writing fired the public imagination, inspiring Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth and Louis Figuier's 1867 second edition of La Terre avant le déluge ("Earth before the Flood"), which included dramatic illustrations of savage men and women wearing animal skins and wielding stone axes, in place of the Garden of Eden shown in the 1863 edition.[6]

The idea of a "missing link" between humans and so-called "lower" animals remains lodged in the public imagination.[7] The search for a fossil showing transitional traits between apes and humans, however, was fruitless until the young Dutch geologist Eugène Dubois found a skullcap, a molar and a femur on the banks of Solo River, Java in 1891. The find combined a low, ape-like skull roof with a brain estimated at around 1000 cc, midway between that of a chimpanzee and an adult man. The single molar was larger than any modern human tooth, but the femur was long and straight, with a knee angle showing that "Java man" had walked upright.[8] Given the name Pithecanthropus erectus ("erect ape-man"), it became the first in what is now a long list of human evolution fossils. At the time it was hailed by many as the "missing link", helping set the term as primarily used for human fossils, though it is sometimes used for other intermediates, like Archaeopteryx.[9][10]

"Missing link" is still a popular term, well recognized by the public and often used in the popular media. It is, however, avoided in the scientific press, as it relates to the concept of the great chain of being and to the notion of simple organisms being primitive versions of complex ones, both of which have been discarded in biology.[11] In any case, the term itself is misleading, as any known transitional fossil, like Java Man, is no longer missing. While each find will give rise to new gaps in the evolutionary story on each side, the discovery of more and more transitional fossils continues to add to our knowledge of evolutionary transitions.[12][13]

References

edit- ^ Lovejoy 1936.

- ^ Lamarck, M. De (1815). Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres. Paris: Déterville.

- ^ Appel, T.A. (1980). "Henri De Blainville and the Animal Series: A Nineteenth-Century Chain of Being". Journal of the History of Biology. 13 (2): 291–319. doi:10.1007/BF00125745. JSTOR 4330767.

- ^ Haeckel & 1912 (reprint 2011), p. 216.

- ^ Bynum W.F. (1984). "Charles Lyell's Antiquity of Man and its critics". Journal of the History of Biology. 17 (2): 153–187. doi:10.1007/BF00143731.

- ^ Browne 2002, pp. 130, 218, 515.

- ^ "Why the term "missing links" is inappropriate". Biology times. 10 June 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ Lewin, Carl C. Swisher III, Garniss H. Curtis, Roger (2002). Java man : how two geologists' dramatic discoveries changed our understanding of the evolutionary path to modern humans. London: Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11473-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hill, John Reader (2011). Missing links : in search of human origins ([Enlarged and updated] ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927685-1.

- ^ Benton, Michael. "Evidence of Evolutionary Transitions". Actionbioscience. American Institute of Biological Sciences. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Carl Zimmer (19 March 2009). "Darwinius: It delivers a pizza, and it lengthens, and it strengthens, and it finds that slipper that's been at large under the chaise lounge [sic] for several weeks ..." Discover Magazine. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ Prothero, D (2008-02-27). "Evolution: What missing link?" (2645). New Scientist: 35–40.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Newly found fossils could link to human ancestor". CBC News. 8 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-08.

It's tempting to call the new species a "missing link" between earlier species and modern humans, but scientists say the concept no longer applies, given new knowledge of human evolution. ... Researchers now say the evolution of humans consisted of a number of diverse species in many branches, not a single smooth line from ape-like species to humans.