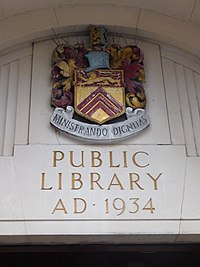

==Leyton Coat of Arms http://www.civicheraldry.co.uk/essex_ob.html#leyton_bc http://www.civicheraldry.co.uk/great_london.html#waltham%20forest%20lb https://www.heraldry-wiki.com/wiki/Leyton The coat of arms of the municipal borough were granted on 27 November 1926. The arms were described as "Or three Chevronels Gules on a Chief Gules a Lion passant Or". The crest was: "On a Wreath Or and Gules a Lion rampant per pale Or and Sable supporting a Crozier Gold". The Latin language motto was "MINISTRANDO DIGNITAS" meaning "dignity in service". Elements of the arms commemorated various families who had held manors within the borough during the Middle Ages, and also the nearby Stratford Langthorne Abbey which had held lands in Leyton before the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[10] The lion and cross-staff on the crest of the Leyton arms have been preserved in the arms of the London Borough of Waltham Forest, which were granted on 1 January 1965.[11]

Tower Hill edit

The well publicised Fascist plan was for their marchers to gather at Tower Hill and the immediate surroundings at 2pm. As the first groups arrived at around 1:25,(REF???) they found Tower Hill held against them by roughly 500 counter-protesters.(EE then and now) A large group of Fascists entering Tower Hil from Mark Lane tube station was attacked by a group of counter-protesters making their way from Aldgate to Tower Hill, while two Fascists were attacked in Mansell Street as they made their way to Tower Hill.(ELA)

1:25 Source

Armoured Vans...

Moran injured

Police secure Tower Hill After it was over a variety of improvised weapons were picked up from the gutters.

Police then attempt to secure the junction (Aldgate reinforcements)

Bit later

A private car bearing the slogan "Mosley shall not pass" drove into Tower Hill and Fascists attacked it before it made its escape\drove off (ELA)(Pathe news)

fascists began to gather at Tower Hill from approximately 2:00 p.m. There were clashes between fascists and anti-fascists at Tower Hill and Mansell Street as they did so, while the anti-fascists also temporarily occupied the Minories.[2]

Sir Thomas More Street edit

Sir Thomas More Street, formerly Nightingale Lane, is a road in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It was formerly the course of a brook, one of the lost rivers of London, whose name has not been recorded.

Toponymy and renaming edit

Nightingale Lane (Ref EPNS)

London County Council renamed the street in 193X as part of a major programme of renaming across the LCC area - the LCC wished to ensure street names were not duplicated in other parts of the capital. Sir Thomas More had no particular connection to the local area.(Ref Darby)

The brook edit

Wellclose Square At or close to the Hermitage Entrance (to the London Dock) Brook at Nightingale Lane (modern Sir Thomas More Street)

boundary feature edit

Events edit

Swans Nest (MLS) - Hermitage given its name to a number of local features such as the Hermitage basin and the Hermitage Entrance

Mill (MLS)

King Charles and the Hunt (Wanstead)

1780 - Gordon Riots

1820 - Tom and Jerry

London Docks - St Katherines and London Docks

Around 1821 the writer Pierce Egan wrote a semi-autobiographical account of a visit to the Coach and Horses public house on Nightingale Lane (now called Sir Thomas More Street) in East Smithfield. The story tells of three upper class friends who tiring of high society events decide to “see a bit of life at the East End of Town”. Egan compares the East Ends informal egalitarian nightlife favourably to the formality of the West End.

every cove that put in his appearance was quite welcome, colour or country considered no obstacle...the group motley indeed; Lascars, blacks, jack tars, coalheavers, dustmen, women of colour, old and young, and a sprinkling of the remnants of once fine girls, &c. were all jigging together

— Pierce Egan, The True History of Tom & Jerry: or, Life in London (1821)[3]

Known monuments and landmarks edit

| Location | Coordinates | Gallery | Description | Conservation Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tower of London | 51°30′28.4″N 0°04′32.2″W / 51.507889°N 0.075611°W | The Tower of London is operated by Historic Royal Palaces and is not open to the public unless a ticket is purchased. | |||

| Tower Hill gardens | 51°30′35.7″N 0°04′33.7″W / 51.509917°N 0.076028°W | Grade 1 Listed Building[4]

List entry number: 1357518 Scheduled Monument[5] List entry number: 1002063 |

Open to the public.

360 panoramic view of this site. | ||

| Tower Hill | 51°30′38.1″N 0°04′34.1″W / 51.510583°N 0.076139°W | Scheduled Monument[6]

List entry number: 1002062 |

Partially accessible to the public. Can be accessed via a

side street for a side-on view (as seen in this picture). For front-on view, access is through the privately owned citizenM Tower of London Hotel. | ||

| Basement of Roman Wall House, 1–2 Crutched Friars and Emperor House | 51°30′43.8″N 0°04′35.4″W / 51.512167°N 0.076500°W | Scheduled Monument[7]

List entry number: 1002069 |

No public access. | ||

| St Alphage Garden | 51°31′05″N 0°05′33″W / 51.5180°N 0.0926°W | Scheduled Monument[8]

List entry number: 1018884 |

Public access. | ||

| London Wall underground car park | 51°31′03.4″N 0°05′25.9″W / 51.517611°N 0.090528°W | Located within the London Wall underground car park. | Scheduled Monument[9]

List entry number: 1018885 |

Open to public. Access through the 24/ 7 London Wall underground car park. | |

| London Wall underground car park | 51°31′03.0″N 0°05′43.5″W / 51.517500°N 0.095417°W | Located within the London Wall underground car park. | Scheduled Monument[10]

List entry number: 1018889 |

No public access – hidden from view. | |

| Aldersgate Street | 51°31′00.2″N 0°05′48.7″W / 51.516722°N 0.096861°W | Located underneath road and pavement.

Gateway name: Aldersgate |

Scheduled Monument[11]

List entry number: 1018882 |

||

| Basement of the Central Criminal Court, Old Bailey | 51°30′55.3″N 0°06′06.1″W / 51.515361°N 0.101694°W | Scheduled Monument[12]

List entry number: 1018884 |

No public access. Potentially arranged to view through a tour within the Old Bailey.[13] |

Related signage edit

| Location | Coordinates | Gallery | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tower Hill

pedestrian crossing |

51°30′34.1″N 0°04′33.1″W / 51.509472°N 0.075861°W | Transcript of the London Wall Walk plaque 1

Transcript of tile 2 'The London Wall Walk The London Wall Walk follows the original line of the City Wall for much of its length, from the royal fortress of the Tower of London to the Museum of London, situated in the modern high-rise development of the Barbican. Between these two landmarks the Wall Walk passes surviving pieces of the Wall visible to the public and the sites of the gates now buried deep beneath the City streets. It also passes close to eight of the surviving forty-one City churches. The Walk is 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) long and is marked by twenty-one panels which can be followed in either direction. Completion of the Walk will take between one and two hours. Wheelchairs can reach most individual sites although access is difficult at some points'. Transcript of tile 5 'For nearly fifteen hundred years the physical growth of the City of London was limited by its defensive wall. The first Wall was built by the Romans c. AD 200, one hundred and fifty years after the foundation of Londinium. It stretched for 2 miles (3.2 km), incorporating a pre-existing fort. In the 4th century, the Romans strengthened the defences with towers on the eastern section of the wall. The Roman Wall formed the foundation of the later City Wall. During the Saxon period the Wall decayed but successive medieval and Tudor rebuildings and repairs restored it as a defensive wall. With the exception of a medieval realignment in the Blackfriars' area, the Wall was no longer necessary for defence. Much of it was demolished in the 18th and 19th centuries and where sections survived they became buried under shops and warehouses. During the 20th century, several sections have been revealed by excavations and preserved'. |

Open to the public. | |

| Tower Hill gardens | 51°30′35.6″N 0°04′34.5″W / 51.509889°N 0.076250°W | Transcript of the London Wall Walk plaque 2

Transcript of tile 1 'The London Wall Walk follows the line of the City Wall from the Tower of London to the Museum of London. The Walk is 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) long and is marked by twenty-one panels which can be followed in either direction. The City Wall was built by the Romans c AD 200. During the Saxon period it fell into decay. From the 12th to 17th centuries large sections of the Roman Wall and gates were repaired or rebuilt. From the 17th century, as London expanded rapidly in size, the Wall was no longer necessary for defence. During the 18th century demolition of parts of the Wall began, and by the 19th century, most of the Wall had disappeared. Only recently have several sections again become visible. Transcript of tile 4 'This impressive section of wall still stands to a height of 35 feet (11 m). The Roman work survives to the level of the sentry walk, 14+1⁄2 feet (4.4 m) high, with medieval stonework above. The Wall was constructed with coursed blocks of ragstone which sandwiched a rubble and mortar core. Layers of flat red tiles were used at intervals to give extra strength and stability. Complete with its battlements the Roman Wall would have been about 20 feet (6.1 m) high. Outside the Wall was a defensive ditch. To the north is the site of one of the towers added to the outside of the wall in the 4th century. Stone recovered from its foundations in 1852 and 1935 included part of the memorial inscription from the tomb of Julius Classicianus. the Roman Provincial Procurator (financial administrator) in AD 61. In the medieval period, the defences were repaired and heightened. The stonework was more irregular with a sentry walk only 3 feet (0.91 m) wide. To the west was the site of the Tower Hill scaffold where many famous prisoners were publicly beheaded, the last in 1747'. |

Open to the public. Note: plaques 3–4 no longer exist in their original spaces as outlined by the maps on the tile within the picture. | |

| Tower Hill gardens | 51°30′35.4″N 0°04′34.0″W / 51.509833°N 0.076111°W | Transcript of the English Heritage plaque

'London Wall This is one of the most impressive surviving sections of London's former city wall. The lower part, with its characteristic tile bonding courses, was built by the Romans around 200 AD. Its purpose may have been as much to control the passage of good and people as for defence. Against its inner face on this side, the wall was reinforced by a substantial earth rampart. Outside was a wide ditch. In the far right hand corner, evidence of an internal turret was found in excavation. This probably contained a staircase giving access to the sentry walk. Complete with its battlements, the Roman wall would have been about 6.4 metres high. During the medieval period, the wall was repaired and heightened. From the 17th century, it fell into disuse and parts were demolished. Several sections, including this one, were preserved by being incorporated into later buildings. For your safety Please take care as historic sites can be hazardous. Children should be kept under close control. Wilful damage to the monument is an offence. Unauthorised use of Metal detectors is prohibited. For more information on this site. and how to join English Heritage, please contact 0171 973 3479 |

Open to the public. | |

| Aldgate Square | 51°30′49.2″N 0°04′37.1″W / 51.513667°N 0.076972°W | Transcript of the London Wall Walk plaque 5

Transcript of tile 1 'The London Wall Walk follows the line of the City Wall from the Tower of London to the Museum of London. The Walk is 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) long and is marked by twenty-one panels which can be followed in either direction. The City Wall was built by the Romans c AD 200. During the Saxon period it fell into decay. From the 12th to 17th centuries large sections of the Roman Wall and gates were repaired or rebuilt. From the 17th century, as London expanded rapidly in size, the Wall was no longer necessary for defence. During the 18th century demolition of parts of the Wall began, and by the 19th century most of the Wall had disappeared. Only recently have several sections again become visible'. Transcript of tile 4 'Aldgate, City Gate When the Roman City Wall was built (c AD 200) a stone gate perhaps already spanned the Roman road linking London (Londinium) with Colchester (Camulodunum). The gate probably had twin entrances flanked by guard towers. Outside the gate a large cemetery developed to the south of the road. In the later 4th century the gate may have been rebuilt to provide a platform for catapults. The Roman gate apparently survived until the medieval period (called Alegate or Algate) when it was rebuilt in 1108–47, and again in 1215. Its continued importance was assured by the building of the great Priory of Holy Trinity just inside the gate. The medieval gate had a single entrance flanked by two large semi-circular towers. It was during this period that Aldgate had lived in rooms over the gate from 1374 while a customs official in the port of London. Aldgate was completely rebuilt in 1607-9 but was finally pulled down in 1761 to improve traffic access'. |

Open to the public. Note: plaque 6 no longer exists in its original space as outlined by the maps on the tile within the picture. | |

| Bevis Marks Street | 51°30′53.3″N 0°04′44.3″W / 51.514806°N 0.078972°W | Transcript of the London Wall Walk plaque 7

Transcript of tile 1 'The London Wall Walk follows the line of the City Wall from the Tower of London to the Museum of London. The Walk is 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) long and is marked by twenty-one panels which can be followed in either direction. The City Wall was built by the Romans c AD 200. During the Saxon period it fell into decay. From the 12th to 17th centuries large sections of the Roman Wall and gates were repaired or rebuilt. From the 17th century, as London expanded rapidly in size, the Wall was no longer necessary for defence. During the 18th century demolition of parts of the Wall began, and by the 19th century most of the Wall had disappeared. Only recently have several sections again become visible'. Transcript of tile 4 'Bevis Marks, City Wall The engraving shows the area around Bevis Marks as it appeared (c 1560–70) in the reign of Elizabeth I. The City Wall, Aldgate, four towers and the City ditch can be clearly seen. Although the Wall has now disappeared in this area many of the streets still survive today. Outside the Wall were wooden tenter frames used for stretching newly woven cloth (the origin of the phrase 'to be on tenter hooks'). A gun foundry can also be seen near St Botolph's Church at the end of Houndsditch. Beyond were open fields (Spital Fields) stretching towards the villages of Shoreditch and Whitechapel. The historian John Stow, writing c 1580, recorded the many unsuccessful attempts to prevent the City ditch becoming a dumping ground for rubbish including the dead dogs, which gave Houndsditch its name. In the 17th century the ditch was finally filled in and the area used for gardens'. |

Open to the public. Note: plaques 8–10 no longer exist in their original spaces as outlined by the maps on the tile within the picture. | |

| Moorgate | Transcript of the London Wall Walk plaque 11

Transcript of tile 1 'The London Wall Walk follows the line of the City Wall from the Tower of London to the Museum of London. The Walk is 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) long and is marked by twenty-one panels which can be followed in either direction. The City Wall was built by the Romans c AD 200. During the Saxon period it fell into decay. From the 12th to 17th centuries large sections of the Roman Wall and gates were repaired or rebuilt. From the 17th century, as London expanded rapidly in size, the Wall was no longer necessary for defence. During the 18th century demolition of parts of the Wall began, and by the 19th century most of the Wall had disappeared. Only recently have several sections again become visible. Tile 5 'Mooregate, Cite Gate. Moorgate was the only gate whose name described its location as it gave access to the moor or marsh which stretched along the northern side of the city. In the early Roman period the area was well-drained by the Walbrook stream by the construction of the City Wall (c AD 200) impeded the natural drainage and caused the formation of a large marsh outside the Wall. There was no Roman gate here but in the Middle Ages a small gate was built. In 1415 it was totally rebuilt by the Mayor Thomas Falconer and the engraving shows it after substantial rebuilding as a single gate, flanked by towers. Throughout the 16th century attempts were made to drain the marsh and within a hundred years the whole area had been laid out with walks and avenues of trees. In 1672 Moorgate was rebuilt as an imposing ceremonial entrance. This was demolished to improve traffic access in 1761. The City Wall to the east became incorporated into the Bethlehem Hospital (Bedlam) for the insane. This long stretch of the Wall was finally demolished in 1817. |

Open to the public. Note: plaques 12 no longer exists in its original space as outlined by the maps on the tile within the picture. | ||

| Open to the public. | ||||

| Open to the public. | ||||

| Open to the public. | ||||

| Open to the public. Note: plaques 16–17 no longer exist in their original spaces as outlined by the maps on the tile within the picture. | ||||

| London Wall underground car park | 51°31′03.6″N 0°05′43.4″W / 51.517667°N 0.095389°W | Transcript of the London Wall Walk plaque 18

Transcript of tile 1 'The London Wall Walk follows the line of the City Wall from the Tower of London to the Museum of London. The Walk is 1+3⁄4 miles (2.8 km) long and is marked by twenty-one panels which can be followed in either direction. The City Wall was built by the Romans c AD 200. During the Saxon period it fell into decay. From the 12th to 17th centuries large sections of the Roman Wall and gates were repaired or rebuilt. From the 17th century, as London expanded rapidly in size, the Wall was no longer necessary for defence. During the 18th century demolition of parts of the Wall began, and by the 19th century most of the Wall had disappeared. Only recently have several sections again become visible'. Transcript of tile 4 'Prior to the construction of the western section of the road London Wall in 1959, excavations revealed the west gate of the Roman fort, built c AD 120. It had twin entrance ways flanked on either side by square towers. Only the northern tower can now be seen. It provided a guardroom and access to the sentry walk along the Wall. Large blocks of sandstone formed the base, some weighing over half a ton (500 kg). The remaining masonry consisted of ragstone brought from Kent. The guardroom opened on to a gravel road, spanning the gates. Each passage was wide enough for a cart and had a pair of heavy wooden doors. Running northwards from the gate-tower is the fort wall, 4 feet (1.2 m) thick with the internal thickening added when the fort was incorporated into the Roman city defences c AD 200. The gate was eventually blocked, probably in the troubled years of the later 4th century. By the medieval period the site of the gate had been completely forgotten'. |

Open to the public. Note: plaques 19–20 no longer exist in their original spaces as outlined by the maps on the tile within the picture. | |

| Open to the public. | ||||

| Aldergate Street – upon the back walls of Alder Castle House, 10 Noble St, London EC2V 7JU | 51°31′00.5″N 0°05′48.6″W / 51.516806°N 0.096833°W | Open to public. |

Elsewhere edit

The church was badly damaged by enemy action in 1940, during the Blitz, and demolished in 1952. Its traced stone footprint and former graveyard remain, as part of Altab Ali Park.[14][15]

Anglo-Saxon London Wall edit

Anglo-Saxon city revival edit

From c. 500, an Anglo-Saxon settlement known as Lundenwic developed in the same area slightly to the west of the old abandoned Roman city.[16] By about 680, London had revived sufficiently to become a major Saxon port. However, the upkeep of the wall was not maintained and London fell victim to two successful Viking assaults in 851 and 886.[17]

In 886 the King of Wessex, Alfred the Great, formally agreed to the terms of the Danish warlord, Guthrum, concerning the area of political and geographical control that had been acquired by the incursion of the Vikings. Within the eastern and northern part of England, with its boundary roughly stretching from London to Chester, the Scandinavians would establish Danelaw.

Anglo-Saxon London Wall restoration edit

In the same year, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that London was "refounded" by Alfred. Archaeological research shows that this involved abandonment of Lundenwic and a revival of life and trade within the old Roman walls. This was part Alfred's policy of building an in-depth defence of the Kingdom of Wessex against the Vikings as well as creating an offensive strategy against the Vikings who controlled Mercia. The burh of Southwark was also created on the south bank of the River Thames during this time.

The city walls of London were repaired as the city slowly grew until about 950 when urban activity increased dramatically.[18] A large Viking army that attacked the London burgh was defeated in 994.[17]

Influence (to shorten) edit

Like most other city walls around England, the London Wall has been largely lost, though a number of fragments remain (see interactive map). The long presence of these walls had had a profound and continuing effect of the character of the City of London, and surrounding areas.[19] The walls constrained the growth of the city, and the location of the limited number of gates and the route of the roads through them shaped development within the walls, and in a much more fundamental way, beyond them. With a few exceptions, the parts of the modern road network heading into the former walled area are the same as those which passed through the former medieval gates.

Whitechapel's spine is the old Roman Road, that ran from the Aldgate on London's Wall, to Colchester in Essex (Roman Britannia's first capital), and beyond. This road, which was later named the Great Essex Road, is now designated the A11. This route has the names Whitechapel High Street and Whitechapel Road as it passes through, or along the boundary, or Whitechapel.[20] For many centuries travellers to and from London on this route were accommodated at the many coaching inns which lined Whitechapel High Street.[14]

Political tensions between Charles I and Parliament in the second quarter of the 17th century led to an attempt by forces loyal to the King to secure the Tower and its valuable contents, including money and munitions. London's Trained Bands, a militia force, were moved into the castle in 1640. Plans for defence were drawn up and gun platforms were built, readying the Tower for war. The preparations were never put to the test. In 1642, Charles I attempted to arrest five members of parliament. When this failed he fled the city, and Parliament retaliated by removing Sir John Byron, the Lieutenant of the Tower. The Trained Bands had switched sides, and now supported Parliament; together with the London citizenry, they blockaded the Tower. With permission from the King, Byron relinquished control of the Tower. Parliament replaced Byron with a man of their own choosing, Sir John Conyers. By the time the English Civil War broke out in November 1642, the Tower of London was already in Parliament's control.[21]

Political tensions between Charles I and Parliament in the second quarter of the 17th century led to an attempt by forces loyal to the King to secure the Tower and its valuable contents, including money and munitions. London's Trained Bands, a militia force, were moved into the castle in 1640. Plans for defence were drawn up and gun platforms were built, readying the Tower for war. The preparations were never put to the test. In 1642, Charles I attempted to arrest five members of parliament. When this failed he fled the city, and Parliament retaliated by removing Sir John Byron, the Lieutenant of the Tower. The Trained Bands had switched sides, and now supported Parliament; together with the London citizenry, they blockaded the Tower. With permission from the King, Byron relinquished control of the Tower. Parliament replaced Byron with a man of their own choosing, Sir John Conyers. By the time the English Civil War broke out in November 1642, the Tower of London was already in Parliament's control.[22]

History edit

Archaeological finds edit

In February 2022, archaeologists from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) announced the discovery of a well-preserved massive Roman mosaic which is believed to date from A.D. 175–225. The dining room (triclinium) mosaic was patterned with knot patterns known as the Solomon's knot and dark red and blue floral and geometric shapes known as guilloche.[23][24][25][26]

Archaeological work at Tabard Street in 2004 discovered a plaque with the earliest reference to 'Londoners' from the Roman period on it.

End of Roman Southwark edit

Londinium was abandoned at the end of the Roman occupation in the early 5th century and both the city and its bridge collapsed in decay. The settlement at Southwark, like the main settlement of London to the north of the bridge, had been more or less abandoned, a little earlier, by the end of the fourth century.[27]

Parishes in Middlesex were grouped into Hundreds, with Hackney part of Ossulstone Hundred. Rapid Population growth around London saw the Hundred split into several "Divisions" during the 1600s, with Hackney part of the Tower Division (aka Tower Hamlets). The Tower Division was noteworthy in that the men of the area owed military service to the Tower of London - and had done even before the creation of the Division.[28]

The area was part of the historic (or ancient) county of Middlesex, but military and most (or all) civil county functions were managed more locally, by the Tower Division (also known as the Tower Hamlets), under the leadership of the Lord-Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets (the post was always filled by the Constable of the Tower of London).

Cable Street

Spartacus background on mosley's growing A-S

Daily Worker - great Alie str

- In 1191 William Longchamp surrendered the Tower to Prince\King after a three day siege.

- In 1214 an under-strength garrison held the force for King John, against a hostile force led by Robert Fitzwalter.

- In 1267 Cardinal Ottobuon held the castle against a strong besieing army?

- In 1381 the castle was taken by around four hundred rebels during the Peasants Revolt. The gates were left open and the garrison did not content the entrance of the rebels.

- 1460 siege link

- In 1471, during the Siege of London, the Tower's Yorkist garrison exchanged fire with Lancastrians holding Southwark, and sallied from the fortress to take part in a pincer movement to attack Lancastrians who were assaulting Aldgate on London's defensive wall.

Tudor and Stuart actions

- In 1571 the Lieutenant of the Tower fired his cannon at City crowds engaged in the xenophobic Evil May Day riots, in which the properties of foreign residents were ransacked. It's not thought that any rioters were hurt by the gunfire, which was was probably meant to merely intimidate the mob.[29]

- Civil war (Skippon?)

Background edit

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) had advertised a march to take place on Sunday 4 October 1936, the fourth anniversary of their organisation. Thousands of BUF followers, dressed in their Blackshirt uniform, intended to march through the heart of the East End, an area which then had a large Jewish population.[30]

The BUF would march from Tower Hill and divide into four columns, each heading for one of four open air public meetings where Mosley and others would address gatherings of BUF supporters:[31][2]

- Salmon Lane, Limehouse at 5pm

- Stafford Road, Bow at 6pm

- Victoria Park Square, Bethnal Green at 6pm

- Aske Street, Shoreditch at 6:30pm

The Jewish People's Council organised a petition, calling for the march to be banned, which gathered the signature of 100,000 East Londoners, including the Mayors of the five East London Boroughs (Hackney, Shoreditch, Stepney, Bethnal Green and Poplar)[32][33] in two days.[34] Home Secretary John Simon denied the request to outlaw the march.[35]

Numbers involved edit

Very large numbers of people took part in the events, in part due to the good weather, but estimates of the numbers of participants vary enormously:

- Estimates of Fascist participants range from 2,000–3,000[36] up to 5,000.[2]

- There were 6,000–7,000 policemen, including the whole of the Metropoltan Police Mounted Division.[36][2][37] The Police had wireless vans and a spotter plane[2] sending updates on crowd numbers and movements to Sir Philip Game's HQ, established on a side street by Tower Hill.[2]

- Estimates of the number of anti-fascist counter-demonstrators range from 100,000[38][2] to 250,000,[39] 300,000,[40] 310,000[41] or more.[42]

Events edit

Tower Hill edit

The fascists began to gather at Tower Hill from approximately 2:00 p.m., there were clashes between fascists and anti-fascists at Tower Hill and Mansell Street as they did so, while the anti-fascists also temporarily occupied the Minories. The BUF set up a casualty dressing station in the Tower Hill area, as did their Independent Labour Party and Communist opponents who each had a dressing station.[2]

1:25 BUF begin to arrive but around 500 waiting for them - clashes (Then & Now) ELA says 2pm

1:40 Roughly 500 surged from Aldgate in the direction of the Minories (Then & Now)

At what point does the car 2pm, police begin to segregate the factions, heavy fighting and counter-protestors pushed into side streets like Dock Street (which led to St George's Highway) (Then & Now)

2:15 - at Aldate shouting "All to Cable Street" - many of whom went by way of leman Street (Then & Now) Assemble at 2?

Aldgate - Still clashes? Just after 3pm - Fenner Brockway makes call. (Battle for EE) 4pm - Headed west (Then & Now)

Other sites such as Limehouse etc (East London Adveriser) Speakers went on for two hours surrounded by police and then hecklers Defused when people told there was no march - close to 5pm 200 waited at Bow (ELA) Various meetings at Hoxton\Shoreditch (ELA)

Cable Street edit

Protesters built a number of barricades on narrow Cable Street and its side streets. The main barricade was by the junction with Christian Street, about 300 metres along Cable Street in the St George in the East area of Wapping. Just west of the main barricade, another barricade was erected on Back Church Lane; the barrier was erected under the railway bridge, just north of the junction with Cable Street.[43]

The Police attempts to take and remove the barricades were resisted in hand-to-hand fighting and also by missiles, including rubbish, rotten vegetables and the contents of chamber pots thrown at the police by women in houses along the street.[44]

Decision at Tower Hill edit

Mosley arrived in an open topped black sports car, escorted by Blackshirt motorcyclists, just before 3:30.[45] By this time, his force had formed up in Royal Mint Street and neighbouring streets into a column nearly half a mile long, and was ready to proceed.[45]

However, the police, fearing more severe disorder if the march and meetings went ahead, instructed Mosley to leave the East End, though the BUF were permitted to march in the West End instead.[34] The BUF event finished in Hyde Park.[46]

Arrests edit

About 150 demonstrators were arrested, with the majority of them being anti-fascists, although some escaped with the help of other demonstrators. Around 175 people were injured including police, women and children.[47][48]

Aftermath edit

The anti-fascists celebrated the community's united response, in which large numbers of East-Enders of all backgrounds; Protestants, Catholics and Jews successfully resisting Mosley. There were few Muslims in London at the time, so they were also delighted when Muslim Somali seaman join the anti-fascist crowds.[49]

The event is frequently cited by modern Antifa movements as "...the moment at which British fascism was decisively defeated".[50][51] The Fascists presented themselves as the law-abiding party who were denied free speech by a weak government and police force in the face of mob violence. After the event the BUF experienced an increase in membership, although their activity in Britain was severely limited.[52]

Following the battle, the Public Order Act 1936 outlawed the wearing of political uniforms and forced organisers of large meetings and demonstrations to obtain police permission. Many of the arrested demonstrators reported harsh treatment at the hands of the police.[53]

Long Ref [2] Short Ref: The Police had wireless vans[54]

next?

Legends around the Roding and lea

A legend St Erkenwald, Bishop of London (E - S)

St Æthelburh, abbess of Barking Abbey

- ^ Waeppa's People – a History of Wapping by Madge Darby – ISBN 0-947699-10-4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lewis, Jon E. (2008). London, The Autobiography. Constable. p. 401. ISBN 978-1-84529-875-3. Lewis uses the East London Advertiser as primary source, and also provides editorial commentary. This source only gives the districts where the meetings would take place, not times or the exact locations. Cite error: The named reference "London, The Autobiography" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Egan P, The True History of Tom & Jerry: or, Life in London, London, Charles Hindley, 1821 https://www.gutenberg.org/files/43504/43504-h/43504-h.htm

- ^ "Porton of Old London Wall, Tower Hamlets – 1357518 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "London Wall: section from underground railway to Tower Hill Guardianship, Tower Hamlets – 1002063 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "London Wall: remains of medieval and Roman wall extending 75yds (68m) N from Trinity Place to railway, City and County of the City of London – 1002062 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "London Wall: remains of Roman wall and bastion (4a) at Crutched Friars, Non Civil Parish – 1002069 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "London Wall: section of Roman and medieval wall at St Alphage Garden, incorporating remains of St Alphage's Church – 1018886 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "London Wall: section of Roman wall within the London Wall underground car park, 25m north of Austral House and 55m north west of Coleman Street, City and County of the City of London – 1018885 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "London Wall: the west gate of Cripplegate fort and a section of Roman wall in London Wall underground car park, adjacent to Noble Street, City and County of the City of London – 1018889 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "London Wall: section of Roman wall and Roman, medieval and post-medieval gateway at Aldersgate, City and County of the City of London – 1018882 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "London Wall: section of Roman wall at the Central Criminal Court, Old Bailey, City and County of the City of London – 1018884 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "The underground secrets of the Old Bailey – London My London | One-stop base to start exploring the most exciting city in the world". Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ a b Ben Weinreb and Christopher Hibbert (eds) (1983) "Whitechapel" in The London Encyclopaedia: 955-6

- ^ Andrew Davies (1990) The East End Nobody Knows: 15–16

- ^ "The early years of Lundenwic". Museum of London. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008.

- ^ a b Wheeler, Kip. "Viking Attacks". Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ Vince, Alan (2001). "London". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- ^ Citadel of the Saxons, the Rise of Early London. Rory Naismith, p31

- ^ 'Stepney: Communications', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green (1998), pp. 7–13 accessed: 9 March 2007

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 74

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 74

- ^ Jeevan Ravindran. "London's largest Roman mosaic in 50 years discovered by archaeologists". CNN. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ Sharp, Sarah Rose (2022-02-24). "Large Roman Mosaic Discovered in Central London". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ Goldstein, Caroline (2022-02-24). "Digging in the Shadows of London's Shard, Archaeologists Discovered a 'Once-in-a-Lifetime Find': a Shockingly Intact Roman Mosaic". Artnet News. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ Solomon, Tessa (2022-02-24). "Archaeologists Uncover London's Largest Roman Mosaic in 50 Years". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ Citadel of the Saxons, Rory Naismith p 35, 2019

- ^ The London Encyclopaedia, 4th Edition, 1983, Weinreb and Hibbert

- ^ John Edward Bowle, Henry VIII, 1964

- ^ hate, HOPE not. "The Battle of Cable Street". www.cablestreet.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Cable Street". History Workshop. 8 January 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

Website shows the original BUF leaflet including exact locations and times

- ^ "Sir Oswald Mosley". Jewish Chronicle. 9 October 1936.

- ^ "ILP souvenir leaflet". Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b Sir Philip Game. "'No pasarán': the Battle of Cable Street". National Archives. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ Piratin, Phil (2006). Our Flag Stays Red. Lawrence & Wishart. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-905007-28-8. cited by Olivia, Lottie Smith (July 2021). Exploring Anti-Fascism in Britain Through Autobiography from 1930 to 1936 (PDF) (MRes). Bournemouth University. p. 72.

- ^ a b Jones, Nigel, Mosley, Haus, 2004, p. 114

- ^ a b Ramsey, Winston G. (1997). The East End, Then and Now. Battle of Britain Prints International Limited. p. 381-389. ISBN 0 900913 99 1.

- ^ Marr, Andrew (2009). The Making of Modern Britain. Macmillan. pp. 317–318. ISBN 978-0-230-70942-3.

- ^ "The official interpretation board at the Cable Street mural". Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "Independent Labour Party leaflet". Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "Daily Chronicle, cited in a TUC Book on Cable Street" (PDF). pp. 11–12. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "TUC Book on Cable Street" (PDF). pp. 11–12. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

It makes reference to contemporary estimates as high as half a million, but does not give a primary source.

- ^ "Recollections and sketches of James Boswell". Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ "Torah For Today: The Battle of Cable Street". Jewish News. 30 April 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Fascist march stopped after disorderly scenes". Guardian newspaper. 5 October 1936. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "Eight decades after the Battle of Cable Street, east London is still united". The Guardian. 16 April 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Brooke, Mike (30 December 2014). "Historian Bill Fishman, witness to 1936 Battle of Cable Street, dies at 93". News. London. Hackney Gazette. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ^ Levine, Joshua (2017). Dunkirk : the history behind the major motion picture. London. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-00-825893-1. OCLC 964378409.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wadsworth-Boyle, Morgan. "The Battle of Cable Street". https://jewishmuseum.org.uk/. Retrieved 2023-11-09.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Penny, Daniel (2017-08-22). "An Intimate History of Antifa". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Webber, G.C. (1984). "Patterns of Membership and Support for the British Union of Fascists". Journal of Contemporary History. 19 (4). Sage Publications Inc.: 575–606. doi:10.1177/002200948401900401. JSTOR 260327. S2CID 159618633. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ Kushner, Anthony and Valman, Nadia (2000) Remembering Cable Street: fascism and anti-fascism in British society. Vallentine Mitchell, p. 182. ISBN 0-85303-361-7

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

The East End, Then and nowwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ The East End then and Now, Winston G Ramsey, Battle of Britain Prints International Limited. 1997, ISBN 0 900913 99 1, p381-389