This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Kingdom of Sardinia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1720–1861 | |||||||||||||||

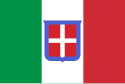

The final flag used by the kingdom under the "perfect fusion" (1848–1861)

| |||||||||||||||

Map of the Kingdom of Sardinia after 1815. | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Turin (1748–1799, 1814–1861) Cagliari (1720-1748, 1799–1814) | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Italain, Sardinian, Piedmontese | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||

• 1720–1730 | Victor Amadeus II | ||||||||||||||

• 1849–1861 | Victor Emmanuel II | ||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||

• 1848 | Cesare Balbo | ||||||||||||||

• 1860–1861 | Camillo Benso | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament (since 1848) | ||||||||||||||

| Royal Senate | |||||||||||||||

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

| 1720 | |||||||||||||||

| 1847 | |||||||||||||||

| 1860 | |||||||||||||||

• Kingdom of Italy proclaimed | March 17 1861 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 1859 | 73,810 km2 (28,500 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Piedmontese shield (mainland, 1720–1800) Sardinian shield (island, 1720–1821) Sardinian lira (1816–61) | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Sardinia (Italian: Regno di Sardegna, Latin: Regnum Sardiniae, Piedmontese: Regn ëd Sardëgna) was a kingdom in Southern Europe from 1720 until 1861 following the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy, its successor state.[1][2] A small island, Sardinia was acquired by the House of Savoy following the award of the crown of Sardinia to King Victor Amadeus II of Savoy from Austria in 1720 under the Treaty of London.[1] The Savoyards united their insular and continental domains and expanded their kingdom—often called Piedmont-Sardinia in this period—into one of the great powers by the time of the Crimean War (1853–56).[3][4] Its final capital, Turin was the center of Savoyard power since the Middle Ages.[5]

When the mainland domains of Nice, Piedmont and Savoy were occupied and eventually annexed by Napoleonic France, the King of Sardinia made his residence once again in the city of Cagliari in Sardinia.[6][7] The Congress of Vienna (1814–15), which restructured Europe in light of Napoleon's defeat, returned to Savoy its mainland possessions and augmented them with the Republic of Genoa.[8] In 1847–48, in a "perfect fusion", the various Savoyard states were unified under one legal system, with its capital in Turin, and granted a constitution, the Statuto Albertino. There followed the annexation of Lombardy (1859), the central Italian states and the Two Sicilies (1860), Venetia (1866) and the Papal States (1870). On 17 March 1861, law no. 4671 of the Sardinian Parliament proclaimed the Kingdom of Italy, ratifying the annexations of all other Italian states to Kingdom of Sardinia.[9]

History

editExchange of Sicily for Sardinia

editThe Spanish domination of Sardinia ended at the beginning of the 18th century, as a result of War of the Spanish succession. By the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, Spain's European empire was divided: Savoy received Sicily and parts of the Duchy of Milan, while Charles VI (the Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria), received the Spanish Netherlands, the Kingdom of Naples, Sardinia, and the bulk of the Duchy of Milan. During the War of the Quadruple Alliance, Victor Amadeus II, duke of Savoy and sovereign of Piedmont, had to agree to yield Sicily to the Austrian Habsburgs and receive Sardinia in exchange. The exchange was formally ratified in the Treaty of The Hague of 17 February 1720. Because the kingdom of Sardinia had existed since the 14th century, the exchange allowed Victor Amadeus to retain the title of king in spite of the loss of Sicily.

Victor Amadeus initially resisted the exchange, and until 1723 continued to style himself King of Sicily rather than King of Sardinia. The state took the official title of Kingdom of Sardinia, Cyprus and Jerusalem, as the house of Savoy still claimed the thrones of Cyprus and Jerusalem, although both had long been under Ottoman rule.

In 1767–1769, Charles Emmanuel III conquered the Maddalena archipelago in the Strait of Bonifacio from the Republic of Genoa, who ruled it with the island of Corsica, and since then the archipelago is still part of the Sardinian region.

Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna

editIn 1792, the Kingdom of Sardinia and the other states of the Savoy Crown joined the First Coalition against the French First Republic, but was beaten in 1796 by Napoleon and forced to conclude the disadvantageous Treaty of Paris (1796), giving the French army free passage through Piedmont. On 6 December 1798 Joubert occupied Turin and forced Charles Emmanuel IV to abdicate and leave for the island of Sardinia. The provisionary government voted to unite Piedmont with France. In 1799 the Austro-Russians briefly occupied the city, but with the Battle of Marengo (1800), the French regained control. The island of Sardinia stayed out of the reach of the French for the rest of the war.

In 1814, the Crown of Savoy enlarged its territories with the addition of the former Republic of Genoa, now a duchy, and it served as a buffer state against France. This was confirmed by the Congress of Vienna. In the reaction after Napoleon, the country was ruled by conservative monarchs: Victor Emmanuel I (1802–21), Charles Felix (1821–31) and Charles Albert (1831–49), who fought at the head of a contingent of his own troops at the Battle of Trocadero, which set the reactionary Ferdinand VII on the Spanish throne. Victor Emanuel I disbanded the entire Code Napoléon and returned the lands and power to the nobility and the Church. This reactionary policy went as far as discouraging the use of roads built by the French. These changes typified Piedmont. The Kingdom of Sardinia industrialized from 1830 onward. A constitution, the Statuto Albertino, was enacted in the year of revolutions, 1848, under liberal pressure: the kingdom, that, until that moment was strictly confined to island, annexed all the other states of the Savoy house but its institutions were deeply transformed: it became a constitutional and very centralized monarchy as the French model; and under the same pressure Charles Albert declared war on Austria. After initial success the war took a turn for the worse and Charles Albert was defeated by Marshal Radetzky at Custozza.

Italian unification

editLike all of Italy, the Kingdom of Sardinia was troubled with political instability, under alternating governments. After a very short and disastrous renewal of the war with Austria in 1849, Charles Albert abdicated on 23 March 1849, in favour of his son Victor Emmanuel II.

In 1852, a liberal ministry under Count Camillo Benso di Cavour was installed, and the Kingdom of Sardinia became the engine driving the Italian Unification. The Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont) took part in the Crimean War, allied with the Ottoman Empire, Britain, and France, and fighting against Russia.

In 1859, France sided with the Kingdom of Sardinia in a war against Austria, the Austro-Sardinian War. Napoleon III didn't keep his promises to Cavour to fight until all of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia had been conquered. Following the bloody battles of Magenta and Solferino, both French victories, Napoleon thought the war too costly to continue and made a separate peace behind Cavour's back in which only Lombardy would be ceded. Due to the Austrian government's refusal to cede any lands to the Kingdom of Sardinia, they agreed to cede Lombardy to Napoleon who in turn then ceded the territory to the Kingdom of Sardinia to avoid 'embarrassing' the defeated Austrians. Cavour angrily resigned from office when it became clear that Victor Emmanuel would accept the deal.

Garibaldi and the Thousand

editOn 5 March 1860, Parma, Tuscany, Modena, and Romagna voted in referenda to join the Kingdom of Sardinia. This alarmed Napoleon who feared a strong Savoyard state on his southeastern border and he insisted that if the Kingdom of Sardinia were to keep the new acquisitions they would have to cede Savoy and Nice to France. This was done after referenda showed over 99.5% majorities in both areas in favour of joining France.

In 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi started his campaign to conquer southern Italy in the name of the Kingdom of Sardinia. He quickly toppled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and marched to Gaeta. Cavour was actually the most satisfied with the unification while Garibaldi wanted to conquer Rome. Garibaldi was too revolutionary for the king and his prime minister.

Towards the Kingdom of Italy

editOn 17 March 1861, law no. 4671 of the Sardinian Parliament proclaimed the Kingdom of Italy, ratifying the annexations of all other Italian states to Kingdom of Sardinia.[9] The institutions and laws of the Kingdom were quickly extended to all Italy, abolishing the administrations of the other regions. Piedmont would become the most dominant and wealthiest region in Italy and the capital of Piedmont, Turin, would remain the Italian capital until 1865 when the capital was moved to Florence; but in contrast, many revolts exploded through the peninsula, especially in Southern Italy. The House of Savoy would rule Italy until 1946 when Italy was declared a republic by referendum.

Currency

editThe currency in use in the mainland domains of the Savoyards was the Piedmontese scudo[10] During the Napoleonic era, it was replaced in general circulation by the French franc. In 1816, after regaining their Piedmontese dominions, the scudo was replaced by the Sardinian lira,[11] which also replaced the Sardinian scudo, the coins that had been in use on the island throughout the period, in 1821.[10]

National Symbols

editWhen the Duchy of Savoy acquired the Kingdom of Sicily in 1713 and the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1723, the Flag of Savoy became the flag of a naval power. This posed the problem that the same flag was already in used by the Knights of Malta. Because of this, the Savoyards modified their flag for use as a naval ensign in various ways, adding the letters FERT in the four cantons, or adding a blue border, or using a blue flag with the Savoy cross in one canton.

Eventually, king Charles Albert adopted the "revolutionary" Italian tricolour, surmonted by the Savoyard shield, as his flag. This flag became the flag of Kingdom of Italy, and the tricolore without the Savoyard inescutcheon remains the flag of Italy.

-

Royal Standard of the Savoyard kings of Sardinia of Savoy dynasty, 1720–1848

-

Flag of Kingdom of Sardinia 1848–1861, the Italian tricolore with the coat of arms of Savoy as an inescutcheon

-

Imperial Eagle of Roman Holy Emperor Charles V with the four Moors of the Kingdom of Sardinia

-

Coat of arms of Savoy House Kings of Sardinia

-

Variant flag used as naval ensign in the late 18th century[citation needed]

-

Variant flag used as naval ensign in the late 18th or early 19th century[citation needed]

Maps

editTerritorial evolution of Italy from 1796 to 1860:

-

1859:Kingdom of Sardinia

-

1860:Kingdom of Sardinia

After the annexation of Lombardy, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Emilian Duchies and Pope's Romagna. -

Maximum expansion of the Kingdom of Sardinia, in 1860

See also

editNotes and references

editNotes

edit- ^ a b "Sardinia (historical kingdom, Italy) -- Encyclopedia Britannica". [[Encyclopedia Britannica]]. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "L'organizzazione dello Stato unitario" (PDF). Rivista trimestrale di diritto pubblico (in Italian): 47–49. 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Ricordo pittorico militare della spedizione sarda in Oriente 1885-56" (PDF) (in Italian). 1884: 11. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Dana Facaros, Michael Pauls. "Cadogan Guides: Sardinia". p. 22. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Sardinia, kingdom of". [[Columbia Encyclopedia|The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia]] (6 ed.). Columbia University Press. 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "Nice". [[Columbia Encyclopedia|The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia]] (6 ed.). Columbia University Press. 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "Piedmont, region, Italy". [[Columbia Encyclopedia|The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia]] (6 ed.). Columbia University Press. 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ The Congress of Vienna, 1 November 1814 — 8 June 1815

- ^ a b "The Changing Faces of Federalism: Institutional Reconfiguration in Europe From East to West". p. 183. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b Krause, Chester L., and Clifford Mishler (1978). Standard Catalog of World Coins (1979 ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873410203.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krause, Chester L., and Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Bibliography

edit- Murtaugh, Frank M. (1991). Cavour and the Economic Modernization of the Kingdom of Sardinia. New York: Garland Publishing Inc. ISBN 9780815306719.

- Hearder, Harry (1986). Italy in the Age of the Risorgimento, 1790–1870. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49146-0.

- Martin, George Whitney (1969). The Red Shirt and the Cross of Savoy. New York: Dodd, Mead and Co. ISBN 0-396-05908-2.

- Storrs, Christopher (1999). War, Diplomacy and the Rise of Savoy, 1690–1720. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55146-3.

- AAVV. (a cura di F. Manconi), La società sarda in età spagnola, Cagliari, Consiglio Regionale della Sardegna, 2 voll., 1992-3

- Blasco Ferrer Eduardo, Crestomazia Sarda dei primi secoli, collana Officina Linguistica, Ilisso, Nuoro, 2003, ISBN 9788887825657

- Boscolo Alberto, La Sardegna bizantina e alto giudicale, Edizioni Della TorreCagliari 1978

- Casula francesco Cesare, La storia di Sardegna, Carlo Delfino Editore, Sassari, 1994, ISBN 8871380843

- Coroneo Roberto, Arte in Sardegna dal IV alla metà dell'XI secolo, edizioni AV, Cagliari, 2011

- Coroneo Roberto, Scultura mediobizantina in Sardegna, Nuoro, Poliedro, 2000,

- De Saint-Severin Charles, Souvenirs d'un sejour en Sardaigne pendant les annés 1821 et 1822, Ayné editeur, Lyon, 1827,

- Ferrer i Mallol Maria Teresa, La guerra d'Arborea alla fine del XIV secolo; From Archivo de la Corona d'Aragon. Colleccion de documentos inéditos. XLVIII

- Gallinari Luciano, Il Giudicato di Cagliari tra XI e XIII secolo. Proposte di interpretazioni istituzionali, in Rivista dell'Istituto di Storia dell'Europa Mediterranea, n°5, 2010

- Luttwak Edward, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantin Empire, The Belknap Press, 2009, ISBN 9780674035195

- Manconi Francesco, La Sardegna al tempo degli Asburgo, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2010, ISBN 9788864290102

- Manconi Francesco, Una piccola provincia di un grande impero, CUEC, Cagliari, 2012, ISBN 8884677882

- Mastino Attilio, Storia della Sardegna Antica, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2005, ISBN 9788889801635

- Meloni Piero, La Sardegna Romana, Chiarella, Sassari, 1980

- Motzo Bachisio Raimondo, Studi sui bizantini in Sardegna e sull'agiografia sarda, Deputazione di Storia Patria della Sardegna, Cagliari, 1987

- Ortu Gian Giacomo, La Sardegna dei Giudici, Il Maestrale, Nuoro, 2005, ISBN 9788889801024

- Paulis Giulio, Lingua e cultura nella Sardegna bizantina : testimonianze linguistiche dell'influsso greco, Sassari, L'Asfodelo, 1983

- Spanu Luigi, Cagliari nel seicento, Edizioni Castello, Cagliari, 1999

- Spanu Pier Giorgio, Dalla Sardegna bizantina alla Sardegna Giudicale, in Orientis Radiata Fulgore, la Sardegna nel contesto storico e culturale bizantino, Atti del Convegno di Studi, 30 novembre – 1 dicembre 2007, Nuove Grafiche Puddu Editore, Ortacesus, 2008

- Tola Pasquale, Codex Diplomaticus Sardiniae voll. 1et 2, Historiae Patriae Monumenta, Tipografia Regia, Torino, 1861

- Veyne Paul, L'Empire Greco-Romain, Editeur Seuil, 2005, ISBN 9782020577984

- Zedda Corrado – Pinna Raimondo, La nascita dei Giudicati. Proposta per lo scioglimento di un enigma storiografico, in Archivio Storico Giuridico di Sassari, seconda serie, n° 12, 2007

Category:Viceroyalties of the Spanish Empire

Category:Former countries in Europe