| Acinetobacter baumannii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | A. baumannii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | |

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram negative bacteria. It is typically a short, almost round, rod-shape (coccobacillus). It can be an opportunistic pathogen in humans, affecting people with compromised immune systems and is becoming increasingly important as a hospital derived infection (nosocomial). It has also been isolated from soil and water samples in the environment.[1] Bacteria of this genus lack flagella, whip-like structures many bacteria use for locomotion, but exhibit twitching or swarming motility. This may be due to the activity of type IV pili (TFP), a pole-like structure that can be extended and retracted. Motility in A. baumannii may also be due to the excretion of exopolysaccharide, creating a film of high molecular weight sugar chains behind the bacterium in order to move forward.[2] Clinical microbiologists typically differentiate members of the Acinetobacter genus from other Moraxellaceae by performing an oxidase test, as Acinetobacter spp. are the only members of the Moraxellaceae that lack cytochrome C oxidases.[3] A. baumannii is part of the ACB complex (A. baumannii, A. calcoaceticus, and Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU). Members of the ACB comlex are difficult to speciate (to determine the specific species of) and comprise the most clinically relevant members of the genus.[4] [5] A. baumannii has also been identified as an ESKAPE pathogen (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species; a group of pathogens with a high rate of antibiotic resistance that are responsible for the a majority of nosocomial infections.[6] Colloquially, A. baumannii is referred to as 'Iraqibacter' due to its seemingly sudden emergence in military treatment facilities during the Iraq War.[7] It has continued to be an issue for veterans and soldiers who serve in Iraq and Afghanistan. Multidrug resistant resistant (MDR) A. baumannii has spread to civilian hospitals in part due to the transport of infected soldiers through multiple medical facilities.[8][9]

Virulence Factors and Determinants edit

Many microbes, including A. baumannii, have several properties that allow them to be more successful as pathogens. These properties may be virulence factors like toxins or toxin delivery systems which directly impact the host cell. They may also be virulence determinants, which are qualities contributing to a microbe's fitness and allow it to survive the host environment but that do not affect the host directly. The following characteristics are just some of the known factors which make A. baumannii effective as a pathogen.

AbaR Resistance Islands edit

Pathogenicity islands are realatively common genetic structures in bacterial pathogens that are comprised of two or more adjacent genes that increase a pathogen's virulence. They may contain genes that encode toxins, coagulate blood, or, as in this case, allow the bacteria to resist antibiotics. AbaR-type resistance islands are typical of MDR A. baumannii, and different variations may be present in a given strain. Each consists of a transposon backbone of approximately 16.3 Kb that facilitates horizontal gene transfer. Transposons allow portions of genetic material to be excised from one spot in the genome and integrate into another. This makes horizontal gene transfer of this and similar pathogenicity islands more likely because when genetic material is taken up by a new bacterium, the transposons allow the pathogenicity island to integrate into the new microorganism's genome. In this case, it would grant the new microorganism the potential to resist certain antibiotics. AbaRs contain several genes for antibiotic resistance all flanked by insertion sequences. These genes provide resistance to aminoglycosides, aminocyclitols, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol. [10][11]

Beta-lactamase edit

A. baumannii has been shown to produce at least one beta-lactamase, which is an enzyme responsible for cleaving the four atom lactam ring typical of beta-lactam antibiotics. Beta-lactam antibiotics are structurally related to penicillin, which inhibits synthesis of the bacterial cell wall. By cleaving the lactam ring, these antibiotics are rendered harmless to the bacteria. The beta-lactamase, OXA-235, was found to be flanked by insertion sequences, suggesting it was acquired by horizontal gene transfer.[12]

Biofilm Formation edit

A. baumannii has been noted for its apparent ability to survive on artificial surfaces for an extended period of time therefore allowing it to persist in the hospital environment. This is thought to be due to its ability to form biofilms.[13] For many biofilm-forming bacteria, the process is mediated by flagella. However for A. baumannii this process seems to be mediated by pili. Further, disruption of the putative pili chaperone and usher genes csuC and csuE were shown to inhibit biofilm formation.[14] The formation of biofilms has been shown to alter the metabolism of microorganisms within the biofilm consequently reducing their sensitivity to antibiotics. This may be due to the fact that less nutrients are available deeper within the biofilm. A slower metabolism can prevent the bacteria from uptaking an antibiotic or performing a vital function fast enough for particular antibiotics to have an effect. They also provide a physical barrier against larger molecules and may prevent dessication of the bacteria.[15] [16]

Capsule edit

Many virulent bacteria possess the ability to generate a protective capsule around each individual cell. This capsule is made of long chains of sugars and provides an extra physical barrier between antibiotics, antibodies, and complement. The association of increased virulence with presence of a capsule was classically demonstrated in Griffith's experiment.A gene cluster responsible for secretion of the polysaccharide capsule has been identified and shown to inhibit the antibiotic effect of complement when grown on ascites fluid. A decrease in killing associated with loss of capsule production was then demonstrated using a rat virulence model. [17][18]

Efflux Pumps edit

Efflux pumps are protein machines that use energy to pump antibiotics and other small molecules that get into the bacterial cytoplasm out of the cell. By constantly pumping antibiotics out of the cell, bacteria can increase the concentration of a given antibiotic that is required to kill them or inhibit their growth when the target of the antibiotic is inside the bacterium. A. baumannii is known to have two major efflux pumps which decrease its susceptibility to antimicrobials. The first, AdeB, has been shown to be responsible for aminoglycoside resistance.[19] The second, AdeDE, is responsible for efflux of a wide range of substrates including tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and various carbapenems. [20]

OmpA edit

Adhesion can be a critical determinant of virulence for bacteria. The ability to attach to host cells allows bacteria to interact with them in various ways, whether by type III secretion system or simply by holding on against the prevailing movement of fluids. Outer membrane protein A has been shown to be involved in the adherence of A. baumannii to epithelial cells. This allows the bacteria to invade the cells through the zipper mechanism.[21] The protein was also shown to localize to the mitochondria of epithelial cells and cause necrosis by stimulating the production of ROS.[22]

Course of Treatment for Infection edit

Because most infections are now multidrug resistant, it is necessary to determine what susceptibilities the particular strain has for treatment to be successful. Traditionally, infections were treated with imipenem or meropenem, but there has been a steady rise in carbapenem resistant A. baumannii.[23] Consequently, treatment methods often fall back on polymixins, particularly colistin.[24] Colistin is considered a drug of last resort because it often causes kidney damage among other side effects.[25] Prevention methods in hospitals focus on increased hand washing and more diligent sterilization procedures.[26]

Occurrence in Veterans Injured in Iraq and Afghanistan edit

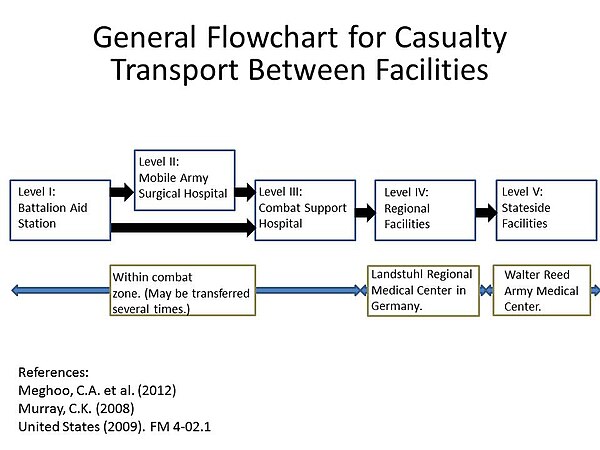

Soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan are at risk for traumatic injury due to gunfire and improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Previously it was thought that infection occurred due to contamination with A. baumannii at the time of injury. Subsequent studies have shown that although A. baumannii may be infrequently isolated from the natural environment, it is much more likely that the infection is nosocomially acquired. This result is likely due to the ability of A. baumannii to persist on artificial surfaces for extended periods, and also the multiple facilities injured soldiers are exposed to during the casualty evacuation process. What a soldier is injured, he or she is first taken to level I facilities where the patient is stabilized. Depending on the severity of the injury, the soldier may then be transferred to a level II facility which consists of a forward surgical team for additional stabilization. Depending on the logistics of the locality, the injured soldier may transfer between these facilities several times before finally being taken to a major hospital within the combat zone (level III). Generally after 1-3 days when the patient is stabilized, they are transferred by air to a regional facility (level IV) for additional treatment. For soldiers serving in Iraq or Afghanistan, this is typically Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany. Finally, the injured soldier is transferred to hospitals in their home country for rehabilitation and additional treatment.[27] This repeated exposure to many different medical environments seems to be the reason A. baumannii infections have become increasingly common. Multidrug resistant A. baumannii is a major factor in complicating the treatment and rehabilitation of injured soldiers, and has led to additional deaths.[28] [29] [30]

Incidence of A. baumannii in Hospitals edit

The importation of A. baumannii and subsequent presence in hospitals has been well documented.[31] A. baumannii is usually introduced into a hospital by a colonized patient. Due to it's ability to survive on artificial surfaces and resist dessication, it can remain and possibly infect new patients for some time. It is suspected that A baumannii is is selected for in hospital settings due to the constant use of antibiotics by patients in the hospital.[32] In a study of European intensive care units in 2009, A. baumannii was found to be responsible for 19.1% of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) cases.[33]

| Country | Reference |

|---|---|

| Australia | [34] [35] |

| Brazil | [36] [37] [38] [39] |

| China | [40] [41] [42] [43] |

| Germany | [44] [45] [46] [47] |

| India | [48] [49] [50] |

| South Korea | [51] [52] [53] [54] |

| United Kingdom | [55] [56] |

| United States | [57] [58] [59] [60] |

References edit

- ^ Yeom, J (2013). "(1)H NMR-Based Metabolite Profiling of Planktonic and Biofilm Cells in Acinetobacter baumannii 1656-2". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e57730. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057730. PMC 3590295. PMID 23483923.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McQueary, C. N.; Kirkup, B. C.; Si, Y.; Barlow, M.; Actis, L. A.; Craft, D. W.; Zurawski, D. V. (2012 Jun). "Extracellular stress and lipopolysaccharide modulate Acinetobacter baumannii surface-associated motility". Journal of Microbiology (Seoul, Korea). 50 (3): 434–43. doi:10.1007/s12275-012-1555-1. PMID 22752907. S2CID 255583564.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Garrity, edited by G. (2000). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology Vol. 2, Pts. A & B: The Proteobacteria (2nd ed., rev. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 454. ISBN 0-387-95040-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ O'Shea, MK (2012 May). "Acinetobacter in modern warfare". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 39 (5): 363–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.018. PMID 22459899.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gerner-Smidt, P (1992 Oct). "Ribotyping of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 30 (10): 2680–5. doi:10.1128/jcm.30.10.2680-2685.1992. PMC 270498. PMID 1383266.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rice, LB (2008 Apr 15). "Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 197 (8): 1079–81. doi:10.1086/533452. PMID 18419525.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Drummond, Katie. "Pentagon to Troop-Killing Superbugs: Resistance Is Futile". Wired.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved 4/8/13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Silberman, Steve. "The Invisible Enemy in Iraq: ACINETOBACTER BAUMANNII". Veterans Today. Retrieved 4/8/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ McQueary, C. N.; Kirkup, B. C.; Si, Y.; Barlow, M.; Actis, L. A.; Craft, D. W.; Zurawski, D. V. (2012 Jun). "Extracellular stress and lipopolysaccharide modulate Acinetobacter baumannii surface-associated motility". Journal of Microbiology (Seoul, Korea). 50 (3): 434–43. doi:10.1007/s12275-012-1555-1. PMID 22752907. S2CID 255583564.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Šeputienė, Vaida; Povilonis, Justas; Sužiedėlienė, Edita (30 January 2012). "Novel Variants of AbaR Resistance Islands with a Common Backbone in Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates of European Clone II". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 56 (4): 1969–1973. doi:10.1128/AAC.05678-11. PMID 22290980. S2CID 30792211.

- ^ Post, V.; White, P. A.; Hall, R. M. (2010 Jun). "Evolution of AbaR-type genomic resistance islands in multiply antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 65 (6): 1162–70. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq095. PMID 20375036.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Higgins, PG (2013 Feb 25). "OXA-235, a novel Class D Beta-Lactamase Involved in Resistance to Carbapenems in Acinetobacter baumannii". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 57 (5): 2121–2126. doi:10.1128/AAC.02413-12. PMC 3632948. PMID 23439638.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Espinal, P.; Martí, S.; Vila, J. (2012 Jan). "Effect of biofilm formation on the survival of Acinetobacter baumannii on dry surfaces". The Journal of Hospital Infection. 80 (1): 56–60. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2011.08.013. PMID 21975219.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Tomaras, A. P.; Dorsey, C. W.; Edelmann, R. E.; Actis, L. A. (2003 Dec). "Attachment to and biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces by Acinetobacter baumannii: involvement of a novel chaperone-usher pili assembly system". Microbiology (Reading, England). 149 (Pt 12): 3473–84. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26541-0. PMID 14663080.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Worthington, RJ (2012 Oct 7). "Small molecule control of bacterial biofilms". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 10 (37): 7457–74. doi:10.1039/c2ob25835h. PMC 3431441. PMID 22733439.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Yeom, J (2013). "(1)H NMR-Based Metabolite Profiling of Planktonic and Biofilm Cells in Acinetobacter baumannii 1656-2". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e57730. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057730. PMC 3590295. PMID 23483923.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kleinman, H. K.; McGarvey, M. L.; Hassell, J. R.; Star, V. L.; Cannon, F. B.; Laurie, G. W.; Martin, G. R. (1986 Jan 28). "Basement membrane complexes with biological activity". Biochemistry. 25 (2): 312–8. doi:10.1021/bi00350a005. PMID 2937447.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Luke, N. R.; Sauberan, S. L.; Russo, T. A.; Beanan, J. M.; Olson, R.; Loehfelm, T. W.; Cox, A. D.; St Michael, F.; Vinogradov, E. V.; Campagnari, A. A. (2010 May). "Identification and characterization of a glycosyltransferase involved in Acinetobacter baumannii lipopolysaccharide core biosynthesis". Infection and Immunity. 78 (5): 2017–23. doi:10.1128/IAI.00016-10. PMC 2863528. PMID 20194587.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Magnet, S.; Courvalin, P.; Lambert, T. (2001 Dec). "Resistance-nodulation-cell division-type efflux pump involved in aminoglycoside resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii strain BM4454". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 45 (12): 3375–80. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.12.3375-3380.2001. PMC 90840. PMID 11709311.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Chau, S. L.; Chu, Y. W.; Houang, E. T. (2004 Oct). "Novel resistance-nodulation-cell division efflux system AdeDE in Acinetobacter genomic DNA group 3". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 48 (10): 4054–5. doi:10.1128/AAC.48.10.4054-4055.2004. PMC 521926. PMID 15388479.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Choi, CH (2008 Dec 10). "Acinetobacter baumannii invades epithelial cells and outer membrane protein A mediates interactions with epithelial cells". BMC Microbiology. 8: 216. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-8-216. PMC 2615016. PMID 19068136.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Lee, J. S.; Choi, C. H.; Kim, J. W.; Lee, J. C. (2010 Jun). "Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A induces dendritic cell death through mitochondrial targeting". Journal of Microbiology (Seoul, Korea). 48 (3): 387–92. doi:10.1007/s12275-010-0155-1. PMID 20571958. S2CID 33040805.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Su, C. H.; Wang, J. T.; Hsiung, C. A.; Chien, L. J.; Chi, C. L.; Yu, H. T.; Chang, F. Y.; Chang, S. C. (2012). "Increase of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection in acute care hospitals in Taiwan: association with hospital antimicrobial usage". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e37788. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037788. PMC 3357347. PMID 22629456.

- ^ Abbo, A.; Navon-Venezia, S.; Hammer-Muntz, O.; Krichali, T.; Siegman-Igra, Y.; Carmeli, Y. (2005 Jan). "Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (1): 22–9. doi:10.3201/eid1101.040001. PMC 3294361. PMID 15705318.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Spapen, H.; Jacobs, R.; Van Gorp, V.; Troubleyn, J.; Honoré, P. M. (2011 May 25). "Renal and neurological side effects of colistin in critically ill patients". Annals of Intensive Care. 1 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/2110-5820-1-14. PMC 3224475. PMID 21906345.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Acinetobacter in Healthcare Settings". CDC. Retrieved 4/8/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Army Medical Logistics" (PDF). FM 4-02.1. United States. Retrieved 4/8/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ O'Shea, MK (2012 May). "Acinetobacter in modern warfare". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 39 (5): 363–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.018. PMID 22459899.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Meghoo, CA (2012 May). "Diagnosis and management of evacuated casualties with cervical vascular injuries resulting from combat-related explosive blasts". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 55 (5): 1329–36, discussion 1336-7. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2011.11.125. PMID 22325667.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Murray, CK (2008 Mar). "Epidemiology of infections associated with combat-related injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan". The Journal of Trauma. 64 (3 Suppl): S232-8. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318163c3f5. PMID 18316967.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Jones, A.; Morgan, D.; Walsh, A.; Turton, J.; Livermore, D.; Pitt, T.; Green, A.; Gill, M.; Mortiboy, D. (2006 Jun). "Importation of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter spp infections with casualties from Iraq". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 6 (6): 317–8. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70471-6. PMID 16728314.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Dijkshoorn, L.; Nemec, A.; Seifert, H. (2007 Dec). "An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 5 (12): 939–51. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1789. PMID 18007677. S2CID 3446152.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Koulenti, D.; Lisboa, T.; Brun-Buisson, C.; Krueger, W.; Macor, A.; Sole-Violan, J.; Diaz, E.; Topeli, A.; Dewaele, J.; Carneiro, A.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Armaganidis, A.; Rello, J.; EU-VAP/CAP Study Group (2009 Aug). "Spectrum of practice in the diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia in patients requiring mechanical ventilation in European intensive care units". Critical Care Medicine. 37 (8): 2360–8. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a037ac. PMID 19531951. S2CID 205537662.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ng, J.; Gosbell, I. B.; Kelly, J. A.; Boyle, M. J.; Ferguson, J. K. (2006 Nov). "Cure of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii central nervous system infections with intraventricular or intrathecal colistin: case series and literature review". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 58 (5): 1078–81. doi:10.1093/jac/dkl347. PMID 16916866.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Farrugia, D. N.; Elbourne, L. D.; Hassan, K. A.; Eijkelkamp, B. A.; Tetu, S. G.; Brown, M. H.; Shah, B. S.; Peleg, A. Y.; Mabbutt, B. C.; Paulsen, I. T. (2013). "The Complete Genome and Phenome of a Community-Acquired Acinetobacter baumannii". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e58628. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058628. PMC 3602452. PMID 23527001.

- ^ Werneck, J. S.; Picão, R. C.; Carvalhaes, C. G.; Cardoso, J. P.; Gales, A. C. (2011 Feb). "OXA-72-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in Brazil: a case report". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 66 (2): 452–4. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq462. PMID 21131320.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Martins, N.; Martins, I. S.; De Freitas, W. V.; De Matos, J. A.; Magalhães, A. C.; Girão, V. B.; Dias, R. C.; De Souza, T. C.; Pellegrino, F. L.; Costa, L. D.; Boasquevisque, C. H.; Nouér, S. A.; Riley, L. W.; Santoro-Lopes, G.; Moreira, B. M. (2012 Jun). "Severe infection in a lung transplant recipient caused by donor-transmitted carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii". Transplant Infectious Disease : An Official Journal of the Transplantation Society. 14 (3): 316–20. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00701.x. PMC 3307813. PMID 22168176.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Superti, S. V.; Martins Dde, S.; Caierão, J.; Soares Fda, S.; Prochnow, T.; Zavascki, A. P. (2009 Mar-Apr). "Indications of carbapenem resistance evolution through heteroresistance as an intermediate stage in Acinetobacter baumannii after carbapenem administration". Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo. 51 (2): 111–3. doi:10.1590/s0036-46652009000200010. PMID 19390741.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gionco, B (2012 Oct). "Detection of OXA-231, a new variant of blaOXA-143, in Acinetobacter baumannii from Brazil: a case report". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 67 (10): 2531–2. doi:10.1093/jac/dks223. PMID 22736746.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zhao, WS (2011 Mar). "Coexistence of blaOXA-23 with armA and novel gyrA mutation in a pandrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolate from the blood of a patient with haematological disease in China". The Journal of Hospital Infection. 77 (3): 278–9. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2010.11.006. PMID 21281989.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Xiao, S. C.; Zhu, S. H.; Xia, Z. F.; Ma, B.; Cheng, D. S. (2009 Nov). "Successful treatment of a critical burn patient with obstinate hyperglycemia and septic shock from pan-drug-resistant strains". Medical Science Monitor : International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 15 (11): CS163-5. PMID 19865060.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wu, Y. C.; Hsieh, T. C.; Sun, S. S.; Wang, C. H.; Yen, K. Y.; Lin, Y. Y.; Kao, C. H. (2009 Nov). "Unexpected cloud-like lesion on gallium-67 scintigraphy: detection of subcutaneous abscess underneath the skin with normal appearance in a comatose patient in an intensive care setting". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 338 (5): 388. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181a6dd36. PMID 19770790.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Duan, X.; Yang, L.; Xia, P. (2010 Mar). "Septic arthritis of the knee caused by antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a gout patient: a rare case report". Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 130 (3): 381–4. doi:10.1007/s00402-009-0958-x. PMID 19707778. S2CID 37311301.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wagner, J. A.; Nenoff, P.; Handrick, W.; Renner, R.; Simon, J.; Treudler, R. (2011 Feb). "[Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Acinetobacter baumannii : A case report]". Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 62 (2): 128–30. doi:10.1007/s00105-010-1962-3. PMID 20835812.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Aivazova, V.; Kainer, F.; Friese, K.; Mylonas, I. (2010 Jan). "Acinetobacter baumannii infection during pregnancy and puerperium". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 281 (1): 171–4. doi:10.1007/s00404-009-1107-z. PMID 19462176. S2CID 23112180.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Schulte, B (2005 Dec). "Clonal spread of meropenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains in hospitals in the Mediterranean region and transmission to South-west Germany". The Journal of Hospital Infection. 61 (4): 356–7. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2005.05.009. PMID 16213625.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wagner, J. A.; Nenoff, P.; Handrick, W.; Renner, R.; Simon, J.; Treudler, R. (2011 Feb). "[Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Acinetobacter baumannii : A case report]". Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 62 (2): 128–30. doi:10.1007/s00105-010-1962-3. PMID 20835812.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Piparsania, S.; Rajput, N.; Bhatambare, G. (2012 Sep-Oct). "Intraventricular polymyxin B for the treatment of neonatal meningo-ventriculitis caused by multi-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii--case report and review of literature". The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics. 54 (5): 548–54. PMID 23427525.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ John, TM (2012 Mar). "Macrophage activation syndrome following Acinetobacter baumannii sepsis". International Journal of Infectious Diseases : IJID : Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 16 (3): e223-4. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2011.12.002. PMID 22285540.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sharma, A.; Shariff, M.; Thukral, S. S.; Shah, A. (2005 Oct). "Chronic community-acquired Acinetobacter pneumonia that responded slowly to rifampicin in the anti-tuberculous regime". The Journal of Infection. 51 (3): e149-52. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2004.12.003. PMID 16230195.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Jeong, H. L.; Yeom, J. S.; Park, J. S.; Seo, J. H.; Park, E. S.; Lim, J. Y.; Park, C. H.; Woo, H. O.; Youn, H. S. (2011 Jul-Aug). "Acinetobacter baumannii isolation in cerebrospinal fluid in a febrile neonate". The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics. 53 (4): 445–7. PMID 21980849.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hong, KB (2012 Jul). "Investigation and control of an outbreak of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 31 (7): 685–90. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e318256f3e6. PMID 22466324. S2CID 1078450.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lee, Y. K.; Kim, J. K.; Oh, S. E.; Lee, J.; Noh, J. W. (2009 Dec). "Successful antibiotic lock therapy in patients with refractory peritonitis". Clinical Nephrology. 72 (6): 488–91. doi:10.5414/cnp72488. PMID 19954727.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lee, S. Y.; Lee, J. W.; Jeong, D. C.; Chung, S. Y.; Chung, D. S.; Kang, J. H. (2008 Aug). "Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter meningitis in a 3-year-old boy treated with i.v. colistin". Pediatrics International : Official Journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 50 (4): 584–5. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02677.x. PMID 18937759. S2CID 42715424.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Adams, D.; Yee, L.; Rimmer, J. A.; Williams, R.; Martin, H.; Ovington, C. (2011 Feb 10-23). "Investigation and management of an A. Baumannii outbreak in ICU". British Journal of Nursing (Mark Allen Publishing). 20 (3): 140, 142, 144–7. doi:10.12968/bjon.2011.20.3.140. PMID 21378633.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Pencavel, T. D.; Singh-Ranger, G.; Crinnion, J. N. (2006 May). "Conservative treatment of an early aortic graft infection due to Acinetobacter baumanii". Annals of Vascular Surgery. 20 (3): 415–7. doi:10.1007/s10016-006-9030-2. PMID 16602028. S2CID 38699601.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gusten, WM (2002 Jan-Feb). "Acinetobacter baumannii pseudomeningitis". Heart & Lung : The Journal of Critical Care. 31 (1): 76–8. doi:10.1067/mhl.2002.120258. PMID 11805753.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fitzpatrick, M. A.; Esterly, J. S.; Postelnick, M. J.; Sutton, S. H. (2012 Jul-Aug). "Successful treatment of extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii peritoneal dialysis peritonitis with intraperitoneal polymyxin B and ampicillin-sulbactam". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 46 (7–8): e17. doi:10.1345/aph.1R086. PMC 8454916. PMID 22811349.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Patel, J. A.; Pacheco, S. M.; Postelnick, M.; Sutton, S. (2011 Aug 15). "Prolonged triple therapy for persistent multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventriculitis". American Journal of Health-system Pharmacy : AJHP : Official Journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 68 (16): 1527–31. doi:10.2146/ajhp100234. PMID 21817084.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sullivan, DR (2010 Jun). "Fatal case of multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii necrotizing fasciitis". The American Surgeon. 76 (6): 651–3. doi:10.1177/000313481007600636. PMID 20583528. S2CID 41059355.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)