United Nations Plaza (often abbreviated UN Plaza or UNP) is a 2.6-acre (1.1 ha) plaza located on the former alignments of Fulton and Leavenworth Streets—in the block bounded by Market, Hyde, McAllister, and 7th Street—in the Civic Center of San Francisco, California. It is located 1⁄4 mi (0.40 km) east of City Hall and is connected to it by the Fulton Mall and Civic Center Plaza. Public transit access is provided by the BART and Muni Metro stops at the Civic Center/UN Plaza station, which has a station entrance within the plaza itself.[1]

| United Nations Plaza | |

|---|---|

UN Plaza features the emblem of the United Nations and a view of San Francisco City Hall, looking west (2010) | |

| Location | Civic Center |

| Nearest city | San Francisco |

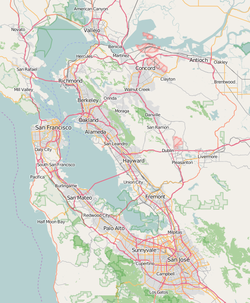

| Coordinates | 37°46′48″N 122°24′50″W / 37.78000°N 122.41389°W |

| Area | 2.6 acres (1.1 ha) |

| Created | 1975 |

| Designer | |

| Public transit access | Muni Metro/BART (Civic Center) |

UN Plaza was designed by a joint venture of firms led by the noted architects Lawrence Halprin, John Carl Warnecke, and Mario Ciampi; Halprin designed the large sunken fountain. The plaza was dedicated in 1975 to commemorate the formation of the United Nations and the signing of the Charter of the United Nations on 26 June 1945 in San Francisco. Since its dedication, the plaza was refurbished in 1995 and 2005, and in Spring 2018, three redesign proposals were proposed for public review.

Location and history

editAfter the 1906 San Francisco earthquake destroyed the old City Hall, the city rebuilt it and other administrative buildings as Civic Center;[2] the key access route to the new Civic Center from Market was along the east–west Fulton Street, which lay parallel to and between McAllister and Grove.[3]: 1 East of Van Ness, the rebuilt City Hall (1915) and Civic Center Plaza (1911) take up two city blocks each between McAllister and Grove, so the two-block eastern portion of Fulton began at the intersection with Larkin and terminated at Market. Currently, the western half of Fulton (from Larkin to Hyde) is known as Fulton Mall; the eastern half (Hyde to Market) is UN Plaza.[4]

UN Plaza also includes a north–south segment built on the former alignment of Leavenworth, which continues north of McAllister. The Leavenworth and Fulton alignments of UN Plaza meet at a right angle; the United Nations Plaza Fountain and entrance to the transit station are where the two alignments meet.[3]: 1 [5]: 5–31

Concept development

editAn east–west pedestrian mall featuring "great bands of trees, a grass mall and paved areas accented by lights and banks of flags [to] expand and extend this central park area [Civic Center Plaza] from the City Hall down Fulton Street to Market" was first proposed as part of the 1958 Civic Center Development Plan. At the time, a new long-distance subway system was being studied with an alignment along Market Street, which would eventually become the Market Street subway serving both BART and Muni Metro.[6]: 9–10 In the following 1962 report What to do About Market Street, landscape architect Lawrence Halprin described his initial vision for the proposed pedestrian mall: "... when the Hyde–Larkin block [of Fulton] is reconstructed (as proposed in [the 1958 Civic Center Development Plan]), views into the Civic Center should be created. Thus our Civic Center, one of the most beautiful in America, could give tremendous support to Market Street."[7]: 31 The proposed pedestrian mall was included in the September 1963 Downtown San Francisco plan prepared by Mario Ciampi for the Department of City Planning.[8]

Independently, in 1965, the first concepts for the Civic Center Station Plaza were sketched out in the Market Street Design Report written by Ciampi and John Carl Warnecke. The concepts for a plaza at Seventh, either straddling Market or south of Market, would serve the future underground transit station and connect to both Fulton Mall (to the west) and the Greyhound bus terminal (to the south).[9]: 76–81 Warnecke and Ciampi updated the concepts for the new plaza in the 1967 Market Street Design Plan, which called for "a major civic sculpture" to dominate "the central space and [create] the focus for the activities of the Plaza".[10] The commission for that major civic sculpture was realized as a fountain, designed by Halprin and completed in 1975.[5]: 4–68

The architecture firm headed by Halprin joined those led by Ciampi and Warnecke in 1968 to form the Market Street Joint Venture Architects, which were responsible for the overarching Market Street Redevelopment Plan.[5]: 4–30 UN Plaza was designed as part of the Market Street/Civic Center Station portion of that plan.[11] The same architectural joint venture was also responsible for the design of the other two large plazas completed earlier along Market: Hallidie Plaza (1973) next to the Powell Street station[12] and Embarcadero Plaza (1972) at the eastern end of Market near the Ferry Building.[5]: 4–30 The Market Street Redevelopment Plan was implemented throughout the 1970s, and was substantially complete by 1979, when Joshua Friedwald documented the results for Halprin & Associates.[13]: 6

Construction

editIn the original design, UN Plaza features included 117,000 sq ft (10,900 m2) of brick paving, laid in a herringbone pattern, and 20,000 sq ft (1,900 m2) of grass lawn.[11] The paving in the southwest part of UN Plaza, near the border with Market Street, is interrupted by a cross formed by granite blocks inlaid with brass which indicate the coordinates of San Francisco used to measure distances to other cities.[5]: 4–67 It is built on the former site of the City Hall that was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake.[14] The pedestrian promenade along the Fulton alignment was lit with 16 light standards and featured 24 wood slat benches along the outer edges along with 192 London plane and black poplar trees. As mentioned above, the focal point was intended to be a large fountain executed in granite slabwork.[11] The design of UN Plaza is credited to the landscape architecture firm of Halprin & Associates, with Don Carter as principal-in-charge, and Angela Danadjieva (who later served as lead designer for Freeway Park in Seattle) as the landscape architect.[15][16]

Several commercial buildings were demolished to make way for the new plaza; only the Orpheum Theater (1925), 1 United Nations Plaza (1932), and the Federal Building (1936) were retained.[5]: 4-66–67 United Nations Plaza was constructed from January to June 1975, following the reconstruction of Market Street after the cut-and-cover excavation for the Market Street subway.[17] It was dedicated in 1975 to commemorate the formation of the United Nations and the 30th anniversary of the signing of the Charter of the United Nations on 26 June 1945 in San Francisco. Mayor Joseph Alioto dedicated the first tree on the plaza—to honor the late UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld—on June 26, 1975.[11]

Refurbishment

editAnniversaries of the United Nations

editIn 1995, for the 50th anniversary of the United Nations, a "Walk of Great Ideas", funded with private donations, was added to the plaza at a cost of US$400,000 (equivalent to $800,000 in 2023).[18] The Walk consisted of eight white granite paving stones inlaid with the preamble to the UN Charter in brass, matching the style of the coordinates cross in the southwest part of the plaza.[5]: 4–81 Additional updates in 1995 included inscribing a list of UN member nations on the light standards, adding the UN emblem to the center of the plaza, engraving the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on an existing 17-foot (5.2 m) tall black granite obelisk, and updating the lighting fixtures.[11][18][19] The original luminaires were semi-translucent and square, matching the shape of the columns; the updated fixtures (which remain today) are frosted glass globes.[5]: 5–33

A new round of refurbishment started in March 2005, at a cost of US$1,500,000 (equivalent to $2,300,000 in 2023),[20] for the 60th anniversary of the UN. Planned improvements included a new stone monument to commemorate UN World Environment Day 2005, hanging the flags of all 191 member nations, and the inscription of new member nation names on the light standards. In addition, the city began to increase the number of events booked for the plaza to encourage "a healthy, vibrant environment that anybody can enjoy."[17][20]

Civic Center Public Realm Plan

editIn 2017, the CMG Landscape Architecture firm was hired by the city planning department to redesign UN Plaza along with the adjoining Civic Center Plaza and Fulton Mall. The design goals of the subsequent Civic Center Public Realm Plan were to retain the scale but encourage pedestrian traffic. CMG unveiled three proposals in Spring 2018:[21]

- Civic Sanctuary, a design "that celebrates History" by evoking the Beaux-Arts spirit of the original plan.[22]

- Culture Connector, billed as "a vision for an inclusive commons that prioritizes Ecology, Wellness, and Variety" which includes additional trees to shade a promenade between Market Street and City Hall.[23]

- Public Platform, "centered on Performance" by creating flexible plazas for temporary activities.[24]

Current uses and events

editRebecca Solnit, a staff writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, called UN Plaza "the spiritual and geographical heart of a considerable territory" because it was "a place where you know where you stand in the world, in the most practical and metaphysical senses" in 2004. Solnit called it a place that "just seems to encourage marching and gathering and walking", a public space that encouraged citizen participation with an active farmer's market and numerous protests near government offices.[25]

Since 1981, the Heart-of-the-City Farmers Market has been held at UN Plaza on Wednesdays and Sundays, which alleviates the food desert that otherwise would exist in Civic Center and the South of Market neighborhoods.[26]

The homeless in San Francisco have long occupied the site, dating back to before the construction of UN Plaza. In 2001, as an attempt to combat homelessness, the city removed the plaza's benches overnight.[15][27] An annual memorial, the Interfaith Homeless Persons Memorial, is held near the winter solstice, the longest night of the year, at UN Plaza to remember the homeless who have died that year.[28][29] The San Francisco Police Department periodically increase patrols and enforcement in the area, and in 2018 parked a mobile command unit at UN Plaza in response to "a number of public complaints about a lot of the behaviors, the drug users, the drug dealers" according to SFPD Chief Bill Scott.[30]

UN Plaza was designed as a pivot point for parades along Market to continue along Fulton Mall to City Hall.[5]: 4–66 Gay Freedom Day Parades in 1977 (drawing 200,000) and 1978 (350,000) were established along that route and were the largest annual parades in San Francisco, which contributed to the city's reputation as a center for LGBTQ activism and culture.[31] From 1985 to 1995, UN Plaza was the site of the AIDS/ARC (or ARC/AIDS) Vigil, the first civil disobedience protest against the AIDS epidemic;[13]: 66 on October 27, 1985, two HIV-positive men, Steve Russell and Frank Bert, chained themselves to the doors of 50 UN Plaza, the regional office for the United States Department of Health and Human Services, to protest the government's inaction on AIDS.[32] The round-the-clock vigil was supported by a camp of volunteers staying in UN Plaza[33][34] and continued to be held there over the next ten years, until a winter storm destroyed the encampment in December 1995.[31][35]

Fountain

editThe fountain in UN Plaza was designed by Lawrence Halprin in collaboration with Ernest Born and completed in 1975.[5]: 4–68 [21][36] The granite slabs are intended to symbolize the continents of Earth, and the lowest central block symbolizes a mythical lost continent. The original design called for water to flood and drain from the basin on a two-minute cycle to simulate the ocean's tides. Aerial jets make the fountain's location visible from the street, and also alert spectators to the start of a new flood/drain cycle.[5]: 4–68 [11] Computer-controlled features were intended to detect wind and attenuate pump output accordingly, to avoid splashing passers-by.[15] The fountain never worked as designed and was fenced off as early as 1978.[37]

Built at a cost of US$1,200,000 (equivalent to $6,790,000 in 2023), the fountain is largely sunken in the surrounding brick plaza, its basin being 100 feet (30 m) wide; and it contains 673 granite blocks over a total length of 165 feet (50 m).[38] Several blocks are inscribed; one carries a quotation from Franklin Delano Roosevelt.[38] According to Halprin, the fountain was meant to be "a place to walk to, sit down, do theater in";[39] and Halprin "claimed to be the first designer to create a space that could actually be used by people."[40] During the design, Halprin applied a concept he dubbed "motation", meaning how an observer's perception of the environment changes depending on their speed and motion.[16]

Shutoff and proposed removal

editIn 1994, the fountain at UN Plaza was proposed to be removed, as it had attracted a significant homeless population, was the site of bird droppings, public bathing, and public urination, and was called "out of scale", an assertion that was rejected by Halprin, the original designer.[11] Because the fountain is registered with the city as part of its civic art collection, removing the fountain would require extensive reviews and public hearings.[19] An assessment completed in 1995 concluded the fountain was not operating as designed, as only a single pump was still working to supply the jets, and the filtration was completely defunct.[11]

Open space creates a kind of vacuum for many people. If the pumps go south and aren't repaired, the fountain goes and the place begins to seem lonely and unattractive. So they become vulnerable.

— Lawrence Halprin, The New York Times, 2003[39]

In March 2003, the city fenced off the fountain and temporarily shut off its water to alleviate the daily burden of cleaning used needles and human feces from it.[41] That same month, a working group commissioned by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors published a report recommending the fountain be removed.[3] Ultimately, the Board of Supervisors rejected the 2003 proposal to remove the fountain.[39] The renewed calls to remove the fountain were based on many of the same reasons as those from ten years prior; an article in The New York Times published in 2004 called the plaza "a public toilet, shower, washing machine, brothel, garbage can and drug market all in one".[42]

Bollards and chains were added around the fountain during the 2005 renovation to prohibit public entry into the fountain;[20] they have since been removed.[40] A metal fence was erected to block off the fountain again in 2018 and replaced with a white plastic fence by April 2019;[43] that was replaced with a high plywood fence in August[44] in preparation for a project to convert part of the fountain's sump into a 15,000 US gal (57,000 L) storage tank for treated non-potable water that will be used to wash streets in Civic Center and the Tenderloin.[45] A branch of the subterranean Hayes Creek had been discovered to run underneath UN Plaza during the construction of the fountain's sump; seepage had been pumped for use in street-cleaning trucks, but that source was abandoned in the 1980s.[46]

Three proposals were advanced in 2018 to redesign the entire Civic Center area, including UN Plaza; of those three, only Civic Sanctuary calls for the restoration of the fountain at UN Plaza.[21] Public Platform would install a new "iconic, interactive fountain" near the present site.[24] Culture Connector would remove the water features altogether and convert the fountain into a bouldering playground.[15] This prompted Linda Day to publish a blog with the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) to protest its potential destruction.[47] In general, the public did not support retaining the fountain;[48] in 2011, a reader survey of Curbed SF found the United Nations Plaza Fountain was one of the least favorite public art pieces in San Francisco.[49]

In February 2019, an updated preliminary concept largely drawn from Public Platform called for a conversion of the fountain into an "interactive fountain and garden" by partially filling it and adding plantings.[50] A follow-up blog posted by the ASLA welcomed the retention of the fountain and the painstaking public outreach process, but expressed skepticism about when (or if) the plan would be implemented.[51]

Critical evaluation

editWhen the fountain was unveiled, Allan Temko, the architecture critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, declared it to be "pretentious schmaltz" that "rarely work[s] and merely toss[es] around empty muscatel bottles."[39][19] At the fountain's 1975 dedication, Andrew Young, United States Ambassador to the United Nations, called it "a tribute to the U.N.'s goals of seeking peaceful resolutions to international rivalries".[19] In a 2007 retrospective, current Chronicle architecture critic John King said the "mannered drama of [Halprin's] plazas along Market Street" collectively "haven't aged well".[52]

Landmark status

editWhen Civic Center was nominated for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), UN Plaza was noted for providing "a pedestrian approach to the Civic Center and a clear view from Market Street to City Hall."[53] UN Plaza is eligible on its own design merits for inclusion on the NRHP, and San Francisco also considers it eligible for inclusion on the California Register of Historic Resources for its original design merits, in addition to its historic role in the LGBTQ movement as the site of parades and protests.[54]

References

edit- ^ "United Nations Plaza". San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ "San Francisco's Civic Center". Engineering News. June 29, 1916. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ a b c United Nations Plaza Working Group; Valente, Lynn (chair) (March 17, 2003). Gateway to the Civic Center: United Nations Plaza Renovation, Presentation of Findings (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Bishari, Nuala Sawyer (May 16, 2018). "City's Humdrum Civic Center May Get a Massive Redesign". SF Weekly. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k ICF (November 2016). Cultural Landscape Evaluation, Better Market Street Project (PDF) (Report). Final. San Francisco Department of Public Works. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Wurster, Bernardi and Emmons, Architects; Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Architects; DeLeuw, Cather & Company, Engineers (1958). San Francisco Civic Center Development Plan (PDF) (Report). The Civic Center Technical Coordinating Committee of the City and County of San Francisco. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Halprin, Lawrence; Carter, Donald Ray; Rockrise, George T. (1962). "The Look of Market Street". What to Do About Market Street: A prospectus for a development program prepared for the Market Street Development Project, an associate of SPUR: The San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association (Report). Livingston and Blayney, City and Regional Planners. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Ciampi, Mario J. (September 1963). Downtown San Francisco — General Plan Proposals (Report). Department of City Planning, City and County of San Francisco. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Mario J. Ciampi & Associates, Architects & Urban Consultants; John Carl Warnecke & Associates, Architects & Planning Consultants (23 June 1965). Market Street design report number 2 – Subway Entrance Plazas (Report). City and County of San Francisco. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Warnecke, John Carl; Ciampi, Mario (1967). Market Street design plan: summary report (Report). Department of City Planning, San Francisco. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h MIG, Inc. (September 16, 2015). San Francisco Civic Center Historic District Cultural Landscape Inventory (PDF) (Report). Planning Department, City and County of San Francisco. pp. 34–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2018. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ King, John (August 16, 2014). "Spoilers: Eyesore buildings that taint their environment". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Appendix 6: Cultural Resources Supporting Information" (PDF). Draft Environmental Impact Report: Better Market Street Project, Planning Department Case no. 2014.0012E (Report). San Francisco Planning Department. February 27, 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Casey, Cindy (July 13, 2015). "Center of San Francisco". Art and Architecture San Francisco. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d Pacheco, Antonio (May 30, 2018). "Another Halprin-designed plaza could be on the chopping block, this time in San Francisco". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ a b "United Nations Plaza". The Landscape Architecture of Lawrence Halprin (PDF). The Cultural Landscape Foundation. 2016. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-9973181-2-8. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Newsom officially marks the start of the United Nations Plaza transformation" (Press release). Office of the Mayor, City of San Francisco. March 9, 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b Epstein, Edward (6 April 1995). "Work Begins on Memorial in U.N. Plaza". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d Lelchuk, Ilene (April 18, 2003). "U.N. Plaza's architect to fight redesign / Famed planner calls S.F. plan no answer to drunks, homeless". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Fagan, Kevin (March 10, 2005). "San Francisco / U.N. Plaza finally getting new look / Spruced-up site to have more events, outdoor markets". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b c King, John (June 29, 2018). "Civic Center makeover: Here's the plan to revamp the heart of SF". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ "Civic Sanctuary". Civic Center Public Realm Plan. 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Culture Connector". Civic Center Public Realm Plan. 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Public Platform". Civic Center Public Realm Plan. 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Solnit, Rebecca (January 11, 2004). "The heart of the city / U.N. Plaza: the beating pulse of public space in San Francisco, from protest to pomegranates". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Winokur, Scott (May 30, 1995). "An urban oasis of life-affirming activity". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Elinson, Zusha (January 28, 2012). "A Renewed Public Push for Somewhere to Sit Outdoors". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "The Vigil: Annual Homeless Persons Memorial". San Francisco Department of Recreation & Parks. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ DeEdoardo, Christina A. (December 26, 2018). "Commentary: Resist: Vigil shows SF's broken policy". The Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Barba, Michael (September 13, 2018). "SFPD Chief Scott pledges to 'restore order' at U.N. Plaza, clear drug users". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ a b Tavel, January; Fike, Aisha (March 29, 2016). Building, Structure, and Object Record: United Nations Plaza (Form DPR 523B) (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Planning Department. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Sachs, Dana (October 1986). "AIDS Vigil Nears First Anniversary". Mother Jones. pp. 11–12. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ McGraw, Carol (March 10, 1986). "AIDS-Related Complex--Its Victims Left in Limbo". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "Finding aid of the AIDS/ARC Vigil Records". Online Archive of California. 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Ingalls, Libby. "AIDS/ARC Vigil 1985–1995". FoundSF. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Brown, Mary (September 30, 2010). San Francisco Modern Architecture and Landscape Design, 1935–1978: Historic Context Statement (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Planning Department. pp. 205–206. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Adams, Gerald (May 15, 1978). "Second look / The new Market Street: Beauty or Bust?". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ a b Casey, Cindy (March 7, 2001). "UN Plaza Fountain". Art and Architecture SF. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Patricia Leigh (July 10, 2003). "For a Shaper of Landscapes, a Cliffhanger". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b Soltz, Wendy (July 2016). "Lawrence Halprin and Two Modern Spaces". Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective. The Ohio State University and Miami University. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ Lelchuk, Ilene (March 12, 2003). "City gives up on U.N. Plaza fountain / Can't keep it clean, puts fence around it". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- ^ Murphy, Dean E. (July 18, 2004). "Letter from San Francisco; A Beautiful Promenade Turns Ugly, and a City Blushes". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Bishari, Nuala Sawyer (April 19, 2019). "UN Plaza Fountain Now Surrounded by Ugly White Fence". SF Weekly. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Mojadad, Ida (August 6, 2019). "Fence Around U.N. Plaza Fountain Upgraded to Plywood Wall". SF Weekly. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ "United Nations Plaza Fountain Project". San Francisco Public Works. 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ "UN Plaza Foundation Drainage Project — Market Street". San Francisco's Non-potable Water Systems Projects (Report). San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. November 2018. pp. 24–25. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Day, Linda (October 15, 2018). "Save Lawrence Halprin's UN Plaza Fountain from Demolition". The Dirt [blog]. American Society of Landscape Architects. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Sabatini, Joshua (May 16, 2019). "Planning Commission president calls for homeless shelter in plans to redo Civic Center". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

[Willett Moss, a founding partner of CMG Landscape Architecture] said that when it came to the fountain, a 'majority of people who responded to surveys and questions would like to see it removed.'

- ^ Pontzer, Abby (April 13, 2011). "'Legs' is Voted San Francisco's Least Favorite". Curbed San Francisco. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ "Public Space Design Concept". Civic Center Public Realm Plan. 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, Grace (March 1, 2019). "A New, Inclusive Civic Center for San Francisco". The Dirt [blog]. American Society of Landscape Architects. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ King, John (March 13, 2007). "A landscape giant looks back at his roots. They go deep". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Charleton, James H. (November 9, 1984). San Francisco Civic Center: National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form (Report). National Park Service. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ AECOM (April 30, 2018). Draft Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration: BART Market Street Canopies and Escalators Modernization Project (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. p. 5-45. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

External links

edit- Lindsay, Georgia (July 2017). "Bricks, branding, and the everyday: Defining greatness at the United Nations Plaza in San Francisco". International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR. 11 (2): 123–136. doi:10.26687/archnet-ijar.v11i2.1159. direct URL Archived 2018-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Roman Mars. "The Biography of 100,000 Square Feet". 99% Invisible (Podcast). SoundCloud.

- "United Nations Plaza". The Cultural Landscape Foundation.

- "Parks: United Nations Plaza". San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection. San Francisco Public Library.