The Twelve Apostles are a common subject in Christian art and serve as a devotional tool for many Christian denominations.[1] They were instrumental in teaching the gospel of Jesus, "continuing the mission of Jesus" with their depictions continuing to serve as spiritual inspiration and authority.[2][3] Many Protestant denominations reject religious imagery, including the veneration of the apostles and other religious figures.[4]

| Twelve Apostles in art | |

|---|---|

| |

| Apostles | Saint Peter, Saint Andrew, James the Great, John the Apostle, Philip the Apostle, Bartholomew the Apostle, Thomas the Apostle, Matthew the Apostle, James, son of Alphaeus, Saint Jude, Saint Simon, Judas Iscariot |

| Media | sculptures, sarcophagi, paintings, prints graffito, frescoes, mosaics, illuminated manuscript, print making, holy cards, devotional medals |

| Associated eras | Paleochristian art, Byzantine art, Medieval art, Renaissance art, Mannerism, Art in the Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation, Baroque art |

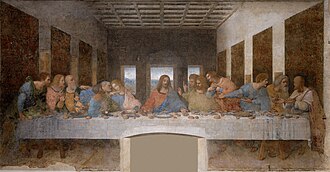

Single portraits are common, or smaller groups, with the full group mostly seen in narrative scenes from the Life of Christ in art, especially The Last Supper. All the apostles acquired distinctive attributes enabling them to be identified, and the most important, such as Saint Peter and Saint John the Beloved, were given a consistent physical appearance. These, and the Four Evangelists, were the most frequently painted. Others were often included in altarpieces and other works because they were the patron saints of the parish, town or province, or of the donor of the work.

Early Christianity edit

The earliest depictions are mostly seen in this period through catacomb frescoes, sarcophagi and icons, with significant Graeco-Roman pagan influence.[5] This was because it was mostly private worship in this period, before the adoption of Christianity in the Roman Empire by Constantine (306–337 CE), when works became more public.[6]

The period used symbolism, influenced from pagan prototypes, in narrative scenes to convey religious meaning rather than beauty, as well as themes of martyrdom, traditio legis (handing over of the law/authority of Christ's teachings), and traditio clavium (giving of the keys) with a specific focus on apostles Peter and Paul, as the ideal teaching figures in the transference of religious authority.[3] The remaining depictions of the Apostles are relatively limited, especially from the Apostolic Age (c. 27–100 CE) and the Ante-Nicene period (100–325 CE). This is due to the lack of patronage and the privatisation of the worship of icons known as graven images.[7]

The oldest known images of some of the apostles are in the catacombs of St Tecla in Rome, dated to the 4th century.[8] The frescoes include Paul, Peter, John and Andrew, serving as a funerary devotional image, to protect the occupants of the tomb.[8] One of the other earliest depictions is in the house church of Dura-Europos, in the baptistery room, from the 3rd or 4th century.[9] It depicts Jesus and Peter walking on water, heralding Christ's power that viewers would hope to gain through "ritual initiation."[10]

The period of late antiquity (313–476 CE), after the Edict of Milan (313 CE), saw an increase in Paleochristian public art, often focused on apostolic authority, due to Constantine's decriminalisation of Christianity.

They were typically depicted in Church works that were more monumental or in sarcophagi during this period. This led to a rise in the cult of saints and apostles as "relics and martyr graves became political instruments."[11]

-

Marble sarcophagus depicting the law delivered to Saint Peter. C. 300-400

-

Paleo-Christian sarcophagus: Christ and his apostles. Genzano, Italy. c. 400.

Early symbols edit

The anchor was a common symbol linked to Peter and Paul, symbolising hope and often found in the epitaphs of catacombs like St. Domitilla.[12] They were also seen with scrolls, Christograms and in an orans pose to establish their authority, sacrifice and connection with God.[13] In the basilica of Saint Paul, the sarcophagus of the Anastasis displayed Peter's arrest, with a "cross, two soldiers and a Christogram," symbolising his martyrdom in reference to both Peter and Paul.[14]

Later periods (476–1750) edit

Middle Ages (500–1500) edit

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, the Roman Catholic Church still funded Christian art. Common media included sculpture, illuminated manuscripts, stained glass, metalwork and mosaics, fresco wall-paintings, tapestry, icons, sarcophagi and psalters or private prayer books. In the earlier periods, works were mostly served as a private devotional tools or liturgical objects such as chalices, phx's (containers for consecrated bread), situlas (bucket for holy water), Processional crosses and chrismatories (containers for holy oil).[15] Liturgical tools were used in public rituals like the Eucharist, which was used to strengthen faith. The start of the Early Middle Ages was a period of political instability, poverty, and death in Western Europe, so public works were not widely commissioned by the church until later in the period.[16][17] The beginning of the Middle Ages saw art using Graeco-Roman style before moving into the diverse styles of Byzantine art, Insular art, Pre-Romanesque, Romanesque art, and Gothic art.

Byzantine era (476–1430) edit

Constantinople's dedication as the new capital of the medieval Roman Empire became a Christian artistic centre during this period, with increased depictions of the apostles and greater distinction between their appearances.[18] Byzantine art produced in the Imperial workshops of the Eastern Orthodox Church had a great influence over western depictions of religious figures, surpassing the traditional Graeco-Roman style.[19]

Portraits were mostly seen in icons, some using tesserae mosaic tiles, and in paintings a gold ground.[20] Icons of the apostles were mostly painted on wood panels with encaustic or egg tempera, but were also carved in stone and ivory and fashioned from mosaics, metals, and enamels.[21] The portraits were highly stylised rather than earlier naturalistic ones, to display religious expression and veneration of the apostles.[19] Byzantine images were mostly seen in churches that favoured flattened figures with standardised facial types which created other worldly images of the apostles, rather than human ones.[22] Depictions in this period emphasised both narrative and symbolic art, to inspire faith of illiterate viewers.[23] This period incorporated more expressive depictions than previous Hellenistic renditions of the icon to encourage the viewer to 'form a personal relationship to holy figures or by entering the narrative'.[24]

The Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople featured these mosaics of the apostles in narrative scenes.This included scenes of communion of the apostles and the doubting Thomas story.[25] One example is the Icon of Peter as a Saint in St. Catherine's Monastery, Egypt dated to the 6th century.[26] The encaustic panel painting foregrounds Peter against his gold halo to display his divinity.[27] He is also holding a cross - symbolising his death and martyr status.[28] Later, the period of Byzantine iconoclasm saw an imperial policy that destroyed and banned icons within the period between 726 and 843, standardising and restricting later depictions of icons.[29] Iconoclasm was a result of the fear of worship of the image, rather than the apostles or holy figure. Instead, the cross only was promoted as a form of decoration in churches.[30] The prohibition against icons was due to verses in Exodus 20:4 which critiqued the worship of graven images.[31][32] Most figurative images were destroyed or plastered over, with exceptions of images at the monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai, Egypt.[33][30] Byzantine art style declined after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.[34]

- Byzantine art

-

Icon of St Peter. St Catherine Monastery, Sinai, c. 600.

-

Transfiguration of Jesus Christ. Jesus appears in the middle between Elijah, Moses, and Apostles James the Great, Peter and John the Apostle. St Catherine Monastery, Sinai, c. 600.

-

Miniature with the Apostles Paul and Peter and the Evangelists John, Luke, Matthew, and Mark. Constantinople, c. 1070 - 1100.

-

Medallion with Saint Peter from an Icon Frame. Constantinople, c.1100.

-

Medallion with Saint Paul from an Icon Frame. Constantinople, c. 1100.

-

Medallion with Saint John the Baptist from an Icon Frame. Constantinople, c.1100.

-

Byzantine iconoclasm. Chludov Psalter, Constantinople, c. 800.

Renaissance (1400–1600) edit

During the Renaissance, the Church sponsored apostolic portraits to make religion more accessible to the laity and those who could not read the scripture.[35] The 'revival' period had a focus on the humanistic, individuality of man.[35] This was reflected in the focus on anatomy, realism, linear perspective and chiaroscuro which made viewers feel more involved with the figures.[36] Apostles were high privileged in this period as martyrs. They acted as a bridge between the divine and the mortals, as well as a tool by the Roman Catholic Church during the Counter-Reformation to forgive Protestant converters.

Famous works depicting the apostles include Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper (c.1495–1498), The Four Apostles (1526) by Albrecht Dürer, Incredulity of Saint Thomas (c.1601–1602) by Caravaggio, and Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul (1661) by Rembrandt. The Protestant reformation, which argued the tenant of 'sola fide' or 'faith alone' against icon worship, lead to the Protestant iconoclasm of the 16th century destroying images.[37] The Catholic church responded by commissioning religious art that was less grandiose, and more contemplative.[38] In the counter-reformation the church often used trusted figures like the apostles to appeal to the masses, as seen in Bernardo Strozzi's Release of St. Peter (1635). Works incorporated stories of apostolic martyrdom to encourage viewers to return to Catholicism.[39]

- Famous works

-

Luca Signorelli, Communion of the Apostles. 1512.

-

Albrecht Dürer, The Four Apostles. 1526. Features Peter, Paul, Mark and John.

-

Jan Sanders van Hemessen, The Calling of Saint Matthew. between 1535-1540

-

Caravaggio, Doubting Thomas. c. 1600.

-

Caravaggio, Crucifixion of Peter. c. 1600.

-

Caravaggio, The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew. C. 1599–1600.

-

El Greco, Saint Thomas. c. 1612.

-

Peter Paul Rubens, Apostle Thomas. c. 1612.

-

Anthony van Dyck, Saint Matthew. c. 1619.

-

Jacob Jordaens, Four apostles. c. 1627.

-

Rembrandt, Bartholomew the Apostle. 1657.

Modern era edit

During the Industrial Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, society became more secular and Christian art started to become collected for appreciation, rather than veneration. However, the creation of colour lithography popularised holy cards in the 19th and 20th century which featured the apostles among other religious figures. Contemporary works often portray conventional religious scenes, with modern revaluations seen in art, film and fashion in the increasingly secular society during the 20th century.[40] In film, the reinvention of depictions of the apostles like Peter is seen in the film Mary Magdalene (2018). Some religious paintings have been well received, including Salvador Dalí's The Sacrament of the Last Supper (1955) which portrayed the apostles in an ethereal surrealist style, whilst incorporating Renaissance elements of mathematical ratios.[41] However most religious conventional art depictions of the apostles have been restricted to devotional work within church settings. Other contemporary instalments of the apostles are often subversive and political. The Last Supper art exhibition in Brooklyn was created with "aims to fill the dearth of Black female voices at the metaphorical table."[42]

Modern depictions been appropriated into fashion, including Off-White's collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. The apparel included prints on hoodies and T-shirts of works like Caravaggio's Madonna of the Rosary, which features Apostle Peter. The exclusive pieces were sold in the pop-up store "Church & State" during Off-White's Chief Executors officer Virgil Abloh's exhibition "Virgil Abloh: Figures of Speech." The pieces featuring the apostles reselling for up to $2000 AUD.[43]

References edit

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Portraits of the Apostles" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Rabali, Tshitangoni C. (13 July 2020). "Bible reading insights from how the gospels and Acts link the apostles to Jesus: A biblical theological exploration". In die Skriflig / In Luce Verbi. 54 (2). doi:10.4102/ids.v54i2.2593. ISSN 2305-0853.

- ^ a b The Apostles in Early Christian Art and Poetry. Roald Dijkstra. Boston. 2016. pp. 377–379. ISBN 978-90-04-30974-6. OCLC 934280118.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Noyes, James, ed. (2013). The Politics of Iconoclasm. I.B. Tauris. doi:10.5040/9780755624515. ISBN 978-0-85773-431-0.

- ^ Jensen, Robin M. (2000). "Art". In Esler, Philip F. (ed.). The Early Christian World. London: Taylor & Francis Group. p. 750. ISBN 9780203778869.

- ^ "Early Christian art". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Spier, Jeffrey. Kessler, Herbert L. (2009). Picturing the Bible : the earliest Christian art. Yale University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-300-14934-0. OCLC 255901295.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Pictures: Oldest Apostle Images Revealed by Laser". History. 26 June 2010. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Peppard, Michael (2016), "Dura-Europos and the World's Oldest Church", The World's Oldest Church, Bible, Art, and Ritual at Dura-Europos, Syria, Yale University Press, pp. 5–45, ISBN 978-0-300-21399-7, JSTOR j.ctt1kft8j0.5, retrieved 6 June 2021

- ^ Peppard, Michael (2016), "Dura-Europos and the World's Oldest Church", The World's Oldest Church, Bible, Art, and Ritual at Dura-Europos, Syria, Yale University Press, p. 41, ISBN 978-0-300-21399-7, JSTOR j.ctt1kft8j0.5, retrieved 6 June 2021

- ^ Dijkstra, Roald (2016). The Apostles in Early Christian Art and Poetry. Netherlands: BRILL. p. 7. doi:10.1163/9789004309746. ISBN 978-90-04-29804-0. OCLC 952059225.

- ^ Kennedy, Charles A. (1975). "Early Christians and the Anchor". The Biblical Archaeologist. 38 (3–4): 119. doi:10.2307/3209591. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3209591. S2CID 187832040.

- ^ Dijkstra, Roald (2016). The Apostles in Early Christian Art and Poetry. Netherlands: BRILL. p. 378. doi:10.1163/9789004309746. ISBN 978-90-04-29804-0. OCLC 952059225.

- ^ Dijkstra, Roald (2016). The apostles in early christian art and poetry. Netherlands: BRILL. p. 364. doi:10.1163/9789004309746. ISBN 978-90-04-30974-6. OCLC 952059225.

- ^ "Art for the Christian Liturgy in the Middle Ages". www.metmuseum.org. October 2001. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ "Private Devotion in Medieval Christianity". www.metmuseum.org. October 2001. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Goldiner, Sigrid (February 2010). "Art and Death in the Middle Ages". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Bogdanović, Jelena (2016). "The Relational Spiritual Geopolitics of Constantinople, the Capital of the Byzantine Empire". Political Landscapes of Capital Cities. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 97–154. ISBN 9781607324690. JSTOR j.ctt1dfnt2b.9.

- ^ a b Hurst, Ellen. "Beginner's guide to Byzantine art & mosaics". Khan Academy. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Byzantine art | Characteristics, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Freeman, Evan. "Icons, an introduction". Khan Academy. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Byzantine art | Characteristics, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Wharton-Epstein, Ann (2004). "The Rebuilding and Redecoration of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople: A Reconsideration". Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. 23: 91.

- ^ "Private Devotion in Medieval Christianity". www.metmuseum.org. 2001. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Wharton-Epstein, Ann (2004). "The Rebuilding and Redecoration of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople: A Reconsideration". Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. 23: 85.

- ^ Bayet, Charles (2009). Byzantine art. Anne Haugen, Jessica Wagner. New York, USA: Parkstone International. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-78042-797-3. OCLC 777400294.

- ^ Bayet, Charles (2009). Byzantine art. Parkstone International. pp. 31g. ISBN 978-1-78042-797-3. OCLC 955645559.

- ^ Freeman, Evan. "Icons, an introduction". Khan Academy. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Brooks, Sarah (August 2009). "Icons and Iconoclasm in Byzantium". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b Brooks, Sarah (2001). "Icons and Iconoclasm in Byzantium". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Brubaker, Leslie (2011). "The beginnings of the image struggle". Inventing Byzantine iconoclasm. London: Duckworth. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-85399-750-1. OCLC 745481463.

- ^ Noyes, James (2013). "Introduction". In Noyes, James (ed.). The Politics of Iconoclasm. I.B. Tauris. p. 4. doi:10.5040/9780755624515. ISBN 978-0-85773-431-0.

- ^ Brubaker, Leslie (2011). "The iconophile intermission". Inventing Byzantine iconoclasm. London: Duckworth. pp. 70–72. ISBN 978-1-85399-750-1. OCLC 745481463.

- ^ Kitzinger, Ernst (1977). Byzantine art in the making : main lines of stylistic development in Mediterranean art, 3rd–7th century. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 1–3. ISBN 0-571-11154-8. OCLC 3597458.

- ^ a b "RELIGIOUS ART throughout THE RENAISSANCE". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ The art of Renaissance Europe : a resource for educators. Bosiljka Raditsa, Alexandra Bonfante-Warren, Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000. pp. 9–15. ISBN 0-87099-953-2. OCLC 43790882.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Heal, Bridget (2017). "Introduction: Art and Religious Reform in Early Modern Europe". Art History. 40 (2): 248. doi:10.1111/1467-8365.12305. hdl:10023/17317. ISSN 1467-8365.

- ^ Heal, Bridget (2017). "Introduction: Art and Religious Reform in Early Modern Europe". Art History. 40 (2): 248. doi:10.1111/1467-8365.12305. hdl:10023/17317. ISSN 1467-8365.

- ^ Freedberg, David (1976). "The Representation of Martyrdoms during The Early Counter-Reformation in Antwerp". The Burlington Magazine. 118 (876): 136. ISSN 0007-6287. JSTOR 878304.

- ^ Deacy, Christopher (2005). Faith in film : religious themes in contemporary cinema. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7546-5158-1. OCLC 1050439123.

- ^ "Revealed: the scientific principles behind Dalí's surrealist eccentricity". the Guardian. 21 February 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Art Exhibition Elevating Voices of Black Women on Show in Brooklyn". BK Reader. 4 March 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Off-White Caravaggio t shirt". Grailed. Retrieved 6 June 2021.