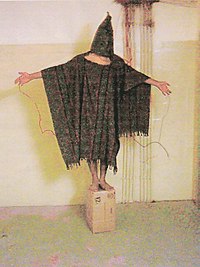

The Hooded Man (or The Man on the Box)[1] is an iconic image showing a prisoner at Abu Ghraib prison with wires attached to his fingers, standing on a box with a covered head. The photo is portrayed as an iconic photograph of the Iraq war[1] and "symbol of the torture at Abu Ghraib".[2][3] The image was published on the cover of The Economist's 8 May 2004 issue, the opening photo of The New Yorker[4] on 10 May 2004,[4][5] and on 11 March 2006[6] in the New York Times's first section at the top left-hand corner.[1]

| The Hooded Man | |

|---|---|

Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, an Iraqi prisoner, being tortured at Abu Ghraib prison by U.S soldiers; the prisoner is standing on the box with wires attached to his left and right hand | |

| Year | 2003 |

| Subject | Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, an Iraqi prisoner |

The man in the photo was initially reported to be Ali Shallal al-Qaisi[1][7] but the online magazine Salon.com later raised doubts about his identity,[6] citing "an examination of 280 Abu Ghraib pictures it has been studying for weeks and on an interview with an official of the Army’s Criminal Investigation Command."[7] It was later reported that Ali Shallal al-Qaisi was photographed in a similar position while being shocked,[8] the real Hooded Man is Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, nicknamed Gilligan.[1][9]

The subject

editThe man under the hood shown in the famous photo was initially reported as Ali Shallal al-Qaysi. Ali was detained at Abu Abu Ghraib for several months between 2003 and 2004, where he was tortured by the U.S. forces. Ali was later released "on a highway away from Abu Ghraib" without being charged with a crime.[10] In his description of the photographed scene, Shallal al-Qaisi states that he was standing on a rigid and "not breakable" box while he received electrical shocks via the wires tied to his hands. "I remember biting my tongue, my eyes felt like they were about to pop out. I started bleeding from under the mask and I fell down," Shallal al-Qaisi adds.[10] “He said he had only recently been given a blanket after remaining naked for days…”[2]

The hooded man identity was later challenged by the online magazine Salon.com after "an examination of 280 Abu Ghraib pictures it has been studying for weeks and on an interview with an official of the Army’s Criminal Investigation Command."[7] Following the challenge, the New York Times said it would investigate the case. Finally, the New York Times reported that "Qaissi acknowledged he is not the man in the specific photograph", though Qaissi and his lawyers say that while being shocked with wires, he was photographed in a similar position.[8] During a phone conversation with the New York Times al-Qaisi said: "I know one thing. I wore that blanket, I stood on that box and I was wired up and electrocuted."[6] Finally, the real identity of the Hooded Man was known to be Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, nicknamed Gilligan.[1][9] The man was not recognized by tribal leaders or the manager of a brick factory located at the address indicated in prison records. It was noted that detainees often assume false identities during their time in custody.[11]

Reception

editThe hooded man image along with the words "Resign, Rumsfeld" were on the cover of the British magazine The Economist, on 8 May 2004[12][13]. It also appeared as the opening photo of Seymour Hersh’s much-quoted essay on 10 May in The New Yorker[4][5] and on 11 March 2006 in The New York Times's first section at the top left-hand corner.[1] The photo was reproduced and published on the cover of The Nation in 26 December 2005 with "The Torture Complex" title being featured with it. On 12 June 2005, The New York Times magazine published a reproduction of The Hooded Man and the title "What We Don't Talk About When We Talk About Torture.".[4]

‘The Hooded Man’’s rise to iconic status has been produced not just by its frequent reproduction but by the numerous ways in which it has been appropriated by image makers across a variety of genres, media, and locations. It has been the template for magazine covers and editorial cartoons, on murals, public posters, sculpture, recreated in Lego, and inserted into paintings and montages.[4]

W. J. T. Mitchell analyzed the Abu Ghraib photos in his book Cloning Terror: the War of Images 9/11 to the Present.[4] The Hooded Man is reportedly one of the three iconic images from a larger set of leaked photos from Abu Ghraib, with the other two being "Pyramid of Bodies" and "Prisoner on a Lesab".[14]

Political impact

editA decade after the public release of the photos of the hooded man, there are numerous publications and debates over Abu Ghraib and the War on Terror which has caused the global circulation of ‘The Hooded Man’. The circulation of this image has led to its widespread recognition as a global icon. It has inspired numerous adaptations across different media and genres, and significant literary works have delved into an analysis of the photograph, its adaptations, and its political significance.[4]

Similar torture cases

editDer Spiegel concludes that many prisoners were tortured and photographed in the same manner as the hooded man shown in the iconic image by the New York Times. According to the experts, the torture suffered by the hooded man has been a standard torture method by the CIA for years. A sworn testimony by the Specialist Sabrina Harman from the 372n Military Police Company states that at least one prisoner was tortured by "fingers, toes and penis wetre attached to wires," while the iconic hooded man has wires attached only to his fingers. Moreover, U.S. investigators say that there were other prisoners, like Satar Jabir, claiming to be the hooded man experiencing the same torture method.[9] In his interview with Der Spiegel, Ali Shallal al-Qaysi named two other people like Shahin, nicknamed "Joker" by the U.S.soldiers, and a man named Saddam al-Rawi, who suffered the same way of torture.[9]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Morris, Errol (15 August 2007). "Will the Real Hooded Man Please Stand Up". Opinionator. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ a b Fattah, Hassan M. (2006-03-11). "Symbol of Abu Ghraib Seeks to Spare Others His Nightmare". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-07-02.

- ^ Soussi, Alasdair. "The Abu Ghraib abuse scandal 20 years on: What redress for victims?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hansen, Lene (2015). "How images make world politics: International icons and the case of Abu Ghraib". Review of International Studies. 41 (2): 263–288. doi:10.1017/S0260210514000199. ISSN 0260-2105.

- ^ a b Hersh, Seymour M. (2004-04-30). "Torture at Abu Ghraib". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2024-07-13.

- ^ a b c Zernike, Kate (2006-03-19). "Hooded at Abu Ghraib, but not in the picture". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-07-13.

- ^ a b c "ID of hooded Abu Ghraib prisoner challenged". NBC News. The Associated Press. 14 March 2006. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Times admits error in ID of Abu Ghraib man". NBC News. 2006-03-18. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- ^ a b c d "Photos from Abu Ghraib: The Hooded Men". Der Spiegel. 2006-03-22. ISSN 2195-1349. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- ^ a b Javaid, Osama Bin (20 Mar 2023). "Abu Ghraib survivor: Taking the hood off 20 years after Iraq war". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ Zernike, Kate (2006-03-18). "Cited as Symbol of Abu Ghraib, Man Admits He Is Not in Photo". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-07-22.

- ^ "Resign, Rumsfeld". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2024-07-02.

- ^ Chatterjee, Pratap (2011-02-03). "Donald Rumsfeld, you're no Robert McNamara". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-07-02.

- ^ Spens, Christiana (2018-12-29). The Portrayal and Punishment of Terrorists in Western Media: Playing the Villain. Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-04882-2.