Te Ua Haumēne was a New Zealand Māori religious leader during the 1860s. He founded the Pai Mārire movement, which became hostile and engaged in military conflict against the New Zealand government during the Second Taranaki War and the East Cape War.

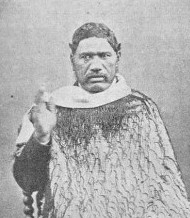

Te Ua Haumēne | |

|---|---|

Te Ua Haumēne in about 1866 | |

| Born | ~1820 |

| Died | ~October 1866 |

| Nationality | Māori |

| Known for | Religious leader |

Early life

editBorn at Waiaua, South Taranaki, in the early 1820s, Te Ua was of the Taranaki iwi (tribe). His father Tūtawake died soon after his son's birth and Te Ua was captured, along with his mother Paihaka, during a 1826 raid mounted by the Waikato iwi. Enslaved, their captors took them to Kāwhia. There was a Christian presence in the area, and Te Ua was taught to read and write and also studied the New Testament.[1] Soon after John Whiteley, a Wesleyan missionary, established a mission station in Kāwhia, Te Ua was baptised as Horopāpera, a transliteration of the name Zerubbabel.[2] He was also known as Horopāpera Tūwhakaroro at this time.[3]

Te Ua returned to the Taranaki in 1840, joining the Wesleyan mission at Waimate. By the 1850s he was a supporter of the Kīngitanga (Māori King Movement) and also engaged in the anti-land-selling movement, protesting the acquisition by settlers of Māori land in the Taranaki. He fought against the government in the First Taranaki War, serving as a chaplain to the Māori warriors.[1]

Foundation of Pai Mārire

editBy 1861, Te Ua was in charge of a rūnanga (council) at Matakaha, tasked with protection of the boundary of land under the domain of Tāwhiao, the Māori King. The grounding on 1 September 1862 of the mail steamer Lord Worsley at Te Namu, which was Kingite land, was considered to be trespass, an act that warranted death. Te Ua wanted the goods recovered from the ship to be taken to New Plymouth. Instead, they were plundered. Troubled by the tension between enforcing Kingite law and espousing Christian love, Te Ua had a vision a few days afterwards. He claimed that the archangel Gabriel proclaimed the last days as foretold in the Book of Revelation was at hand and that he, Te Ua, had been selected as a prophet of God. He was ordered to overthrow the control of the colonists so that the Māori people could reclaim their right to the land.[1][4]

Te Ua began setting up a church and writing prayers and doctrines for his faith, which he called Pai Mārire and considered to be Christianity untainted by the teaching of missionaries. A key aspect was pai mārire (goodness and peace) and much of his teachings were derived from the parables of Jesus. He called his church Hauhau, in homage to hau (wind) carrying the niu (news) to his followers.[1] A key ritual was creating poles strung with ropes and flags, the noise of which as they cracked in the wind, were believed to carried messages. By the following year, he had completed what he called Ua Rongopai (the gospel of Ua), a book of his prayers and gospel.[5] He himself assumed the name Haumēne (Windman).[1]

Although he appears to have been considered an eccentric for some time prior to establishing his faith, particularly among the colonists, Te Ua found a receptive audience in the local Māori and was soon attributed to having performed miracles.[6] Many Māori in Taranaki were alienated from the government due to the ongoing disputes over customary land and there was also animosity towards missionaries.[1]

Conflict

editThe Hauhau came into conflict with the government in April 1864, when followers of Te Ua ambushed and killed several soldiers at Ahuahu, in Taranaki. The bodies were decapitated and Te Ua took possession of the heads, which had been preserved, considering them a symbol of the triumph of good over evil. The heads were later carried around the country by adherents of Pai Mārire as they spread Te Ua's gospel. A series of engagements between Hauhau followers, led by key members of Te Ua's religion, and government forces followed. These resulted in defeats, which Te Ua put down to his followers not adhering to his instructions.[1][5]

In the meantime, Te Ua, living at Pākaraka, near the Waitōtara River, advocated for peace and sought reconciliation, corresponding with government officials as well as colonists. The Māori King became an adherent of Te Ua, and visited him. This caused further tension with the government, which was threatened by the Kīngitanga movement.[1] Another issue was the tension between iwi as Pai Mārire expanded; some saw it as a threat to their own independence within Māoridom. The government supported those factions that were against Pai Mārire.[7]

At the end of the year, a key leader of the Hauhau, Kereopa Te Rau was sent to the East Cape to gain support for the Pai Mārire among the Ngāti Porou iwi of Tūranga. However, disobeying his instructions to proceed peacefully, Kereopa instead agitated for action to be taken against the missionaries as he travelled across the North Island. This culminated in the murder of Reverend Carl Völkner, a supporter of the government, at Ōpōtiki on 2 March 1865. This created considerable anger among the colonists and following this event, Hauhau became a term used to describe any anti-government Māori. Ngāti Porou, aligned with the government, sent forces to fight against the militant Hauhau followers in the area. This resulted in conflict which continued, on and off, until 1872.[1]

Te Ua recognised that the conflict with the government could not continue and commenced discussions with officials to end it. These were unsuccessful in face of likely retribution in the form of land confiscation, which only hardened the resolve to resist the government. There was also the threat of the introduction of government troops into the Taranaki. In the interim, Te Ua continued to preach, advocating for Māori rights for land not yet sold. His religion continued to expand, gaining followers and new prophets were consecrated at the end of 1865.[1]

Later life

editIn February 1866 Te Ua surrendered to Major General Trevor Chute, leading a government expedition to the Taranaki for the purpose of suppressing the Māori dissidents in the area. He was placed under house arrest at Kawau Island, where the Governor of New Zealand, Sir George Grey, had his residence. His confinement ended in June and he was permitted to return to Taranaki, where he encouraged the local Māori to cease their hostile actions against the government. He died in October 1866 at Ōeo. The cause of death may have been tuberculosis.[1]

Legacy

editPai Mārire continued to influence the Kīngitana movement and Tāwhiao, who had been baptised by Te Ua in 1864, ensured its teachings were spread throughout the King Country. Tītokowaru, a war leader in Taranaki, was another influenced by the teachings of Te Ua, and combined elements of Pai Mārire into his own religion.[5]

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Head, Lyndsay. "Te Ua Haumēne". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Newman 2013, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Baker, Matiu; Cooper, Catherine Elizabeth; Fitzgerald, Michael; Rice, Rebecca (1 March 2024). Te Ata o Tū: The Shadow of Tūmatauenga: The New Zealand Wars Collections of Te Papa: The Shadow of Tūmatauenga, The New Zealand Wars Collections of Te Papa. Te Papa Press.

- ^ Babbage 1937, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Binney, Judith. "Te Ua Haumēne – Pai Mārire and Hauhau". Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry of Culture & Heritage. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Babbage 1937, pp. 24–26.

- ^ "Pai Mārire". New Zealand History. Ministry of Culture & Heritage. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

References

edit- Babbage, Stuart Barton (1937). Hauhauism: An Episode in the Maori Wars 1863–1866. Wellington, New Zealand: Reed Publishing.

- Newman, Keith (2013). Beyond Betrayal: Trouble in the Promised Land – Restoring the Mission to Māori. Auckland, New Zealand: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-143-57051-6.