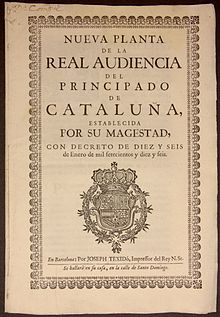

Princeps namque was one of the Usages of Barcelona which regulate the defense of the prince and Principality of Catalonia, and the organising of its military forces. Included in the first Usages of the 11th Century, it was explicitly included in the Usages until the end of the 16th Century. It was repealed with the Nueva Planta decrees promulgated by Philip V, following the defeat of the Catalan supporters of Archduke Charles in the War of the Spanish Succession (1714), one of the effects of which was the suppression of the army led by General Moragues during the war, the sometent, an institution with the philosophy of national defense which despite this temporary suppression, was reestablished in 1794 by the Count of the Union during the Roussillon War (1793-1795), mainly due to the poor situation of the army, and was used again during the Spanish War of Independence (1808-1814), against the French Army in Roses, Barcelona and Tarragona.[1]

History

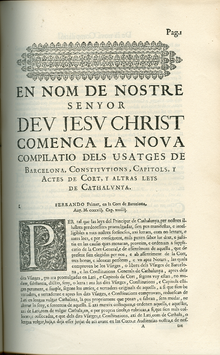

editThe term Princeps namque is derived from the first two words, in Latin, of Usatge 68 (although in some compilations it is number 69):

Princeps namque si quolibet casu obsessus fuerit, uel ipse ídem suos inimicos obsessos tenuerit, uel audierit quemlibet regem uel principem [2]

If the prince for any reason is besieged, or has his enemies besieged, or hears of a coming king or prince...[3] ).

The prince had the power to call to arms the noble feudal lords and all men useful for defense in the event of a threat to his person or an invasion of the territory. The assistance had to be as fast as possible, otherwise they were considered guilty of breach of duty, since "no one can fail the prince in such an important matter". It could only be invoked if the prince was present. It was not valid outside the Principality, and implied the right and duty of the Catalans to possess arms, which became an obligation with Pere the Ceremonious . [4]

In the Courts of Barcelona in 1368, the call was regulated with the contribution of a servant (combatant) for every 15 fires, passing the responsibility of mobilization to the councilors of the commune . [5] In 1374 it was agreed to exchange the service for an amount of money with which the most fit men were hired for combat, so that it became a fogage or war tax. However, the general mobilization was maintained by invoking the princeps namque through the sometent (ringing of bells, or sound emitting ). [6] The institution of princeps namque transcended feudal ties and constituted a commitment between the prince and the entire population. It promoted the notion of self-defense, the formation of militias, the possession and display of weapons, and the refusal to participate in armies and foreign wars.

Invocation

editThe usage was activated by Peter II the Great during the Crusade against the Crown of Aragon, by Peter III the Ceremonious during the Confiscation of the Kingdom of Mallorca and the War of the Two Fathers, [7] by John the Faithless during Siege of Perpignan in 1474 [8] and by Ferdinand I of Antequera during the Revolt of the Count of Urgell . [9] The second half of the segle xiv was the period in which the usage was most often invoked. In 1640 the princeps namque acquired political significance. The Catalan Courts repeatedly rejected the institution of the Union of Arms of the Duke of Olivares, as it was intended for foreign wars against customs. During the War of the Reapers the population was mobilized alongside the General's Deputation, and to raise an Army of the Principality [10] against the troops of Felipe IV of Castile .

Text

editIn latin

editPrinceps namque si quolibet casu obsessus fuerit, uel ipse ídem suos inimicos obsessos tenuerit, uel audierit quemlibet regem uel principem contra se uenire ad debellandum, et terram suam ad succurrendum sibi monuerit, tam per litteras quam per nuncios uel per consuetudines quibus solet amaneri terra, ui delicet per fars, omnes nomines, tam milites quam pedites, qui habeant etatem et posse pugnandi, statim ut hec audierint uel uiderint, quam cicius poterint ei succurrant. Et si quis ei fallerit de iuuamine quod in hoc sibi faceré poterit, perderé debet in perpetuum cuneta que per illum habet; et qui honorem per eum non tenuerit, emendet ei fallimentum et deshonorem quem ei fecerit, cum auere et sacramento manibus propriis iurando, quoniam nema debat fallere ad principem ad tantum opus uel necessitatem

Translation

editIf by any chance the Prince will be besieged, or he will have his enemies besieged, or he will hear some King or Prince coming against him to battle, he will warn his land, which he acknowledges by letters or messages, or by customs with which the admonished land, it is with barons all men like this Knights, like pawns who are old enough to fight, who will hear or see this, how come they all come to his aid. And if no one will fail to help him in this way, he will lose all the time he has for him. And the one who will have nothing for himself, amends the failure, it is the dishonor that has been done to him, by having, it is by sacrament, swearing with his own hands. Because no one should fail the Prince in such a great opus, or necessity.

In medieval catalan

editLo Príncep si per qualque cas será assetiat, ó ell tendrá sos inimichs assetiats, ó oirá algún Rey ó Príncep venir contra sí á batallar, amonestará sa terra, que li aconega per letras ó per missatjes, ó per costumas ab las quals sol ésser la terra amonestada, ço es ab baróns tots homens així Cavallers, com pedóns qui hajan edat é poder de combatre, qui açó oirán ni veurán, com pus tots puxan li vajan socorre. E si ningú li fallirá de la ajuda que en açó fer li pora, perdre den tots temps tot quant per ell tenga. E cell qui per ell res no tindrá, esmenli lo falliment, é la deshonor que feta li haurá, ab haver, é ab sagrament, jurant ab las propias mans. Car ningún hom no deu fallir al Príncep á tant gran ops, ó necessitat.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Bruniquer, Esteban Gilberto, Ceremonial dels Magnífichs Consellers y regiment de la ciutat de Barcelona Archived 2010-01-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sánchez Martínez, Manuel (2001). "La convocatoria del usatge Princeps namque en 1368 y sus repercusiones en la ciudad de Barcelona" (PDF). Barcelona quaderns d'història. núm. 4. Barcelona: 81. ISSN 1135-3058. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ Escartín, Eduard (1998). "El usatge "princeps namque" en la edad moderna". In Ramón Casterás Archidona (ed.). Profesor Nazario González: una historia abierta. Barcelona: Edicions Universitat Barcelona. p. 103. ISBN 9788447519514.

- ^ Gonzalez Calleja, Eduardo (1995). La defensa armada contra la revolución: Una historia de las guardias cívicas en la españa del siglo XX (in Catalan). CSIC. p. 58. ISBN 8400075528.

- ^ Morello Baget, Jordi (2001). Fiscalitat i deute públic en dues viles del Camp de Tarragona: Reus i Valls, segles XIV-XV. CSIC. p. 184. ISBN 8400060164.

- ^ Prats, Joan de Déu (2009). Llegendes històriques de Barcelona. L'Abadia de Montserrat. ISBN 978-8498830644.

- ^ Sanchez Martinez, Manuel (2003). Pagar al Rey en la Corona de Aragón durante el siglo XIV: Estudios sobre fiscalidad y finanzas reales y urbanas. CSIC. p. 180. ISBN 8400081935.

- ^ Vicens Vives, Jaume (2003). Paul Freedman i Josep Mª Muñoz i Lloret (ed.). Juan II de Aragón (1398-1479): monarquía y revolución en la España del siglo XV (in Catalan). Pamplona: Urgoiti editores. p. 364-365. ISBN 84-932479-8-7.

- ^ Riart, Francesc (2010). La Coronela de Barcelona. 1705-1714. Barcelona: Rafael Dalmau, Editor. p. 11. ISBN 9788423207503.

- ^ Passola i Tejedor, Antoni. "Oligarquía, municipio y corona en la Lleida de los Austrias" (PDF) (in Catalan).