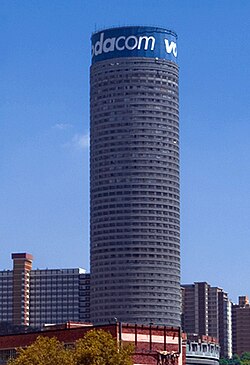

Ponte City[1] is a skyscraper in the Berea district of Johannesburg, South Africa, just next to Hillbrow. It was built in 1975 to a height of 173 m (567.6 ft), and was the tallest residential skyscraper in Africa for 48 years, until overtaken in 2023 by Building D01, in Egypt's New Administrative Capital. The 55-storey building is cylindrical, with an open centre allowing additional light into the apartments. The centre space is known as "the core" and rises above an uneven rock floor. When built, Ponte City was seen as an extremely desirable address due to its location and views over Johannesburg, but it became infamous for its crime and poor maintenance in the late 1980s to 1990s. It has since been refurbished into a safe property. The neon sign on top of the building is the largest sign in the Southern Hemisphere. Prior to 2000, it advertised the Coca-Cola Company.[2] In 2000, this was replaced by a banner promoting South African branch of Vodacom.[3] Vodacom rebranded in 2023 to advertise VodaPay, a digital wallet system.

| Ponte City Apartments | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type | Residential |

| Location | Berea, Johannesburg, South Africa |

| Coordinates | 26°11′26″S 28°3′25.5″E / 26.19056°S 28.057083°E |

| Completed | 1975 |

| Height | |

| Roof | 173 m (567.6 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 55 |

| Lifts/elevators | 8 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Designed by Manfred Hermer |

| Other information | |

| Parking | Available |

History

editThe principal designer of Ponte was Mannie Feldman, working in a team together with Manfred Hermer and Rodney Grosskopff.[4][5] Grosskopff recalled the decision to make the building circular, the first cylindrical skyscraper in Africa.[6] The design--cylindrical shape and concrete material--and urban concept--a city within a city with services and shops on site--was borrowed from Chicago architect Bertrand Goldberg's Marina City (1964), at a time that architectural historian Clive Chipkin calls the "great apartheid building boom," when several Johannesburg firms were borrowing Chicago forms.[7][8] At the time, Johannesburg bylaws required kitchens and bathrooms to have a window, so Grosskopff designed the building with a hollow interior open to the sky, allowing light to enter the wedge-shaped apartments from both the street and the atrium.[6] At the bottom of the immense building were retail stores and initial plans to include an indoor ski slope on the 3,000-square-metre (32,000 sq ft) inner core floor.[6] The building is located 35 minutes from the OR Tambo International Airport and almost within walking distance of the inner city with theatres like the Market and the Civic within 5 km (3.1 mi).[3]

Decay

editDuring the late 1980s, gang activity had caused the crime rate to soar at the tower and the surrounding neighbourhood.[3] By the 1990s, many gangs moved into the building and it became extremely unsafe. Ponte City became symbolic of the crime and urban decay gripping the once cosmopolitan inner city area comprising Berea and neighboring Hillbrow. The open-air core of the building filled with rubbish five stories high as the owners left the building to decay.[9][6]

There was speculation in the mid-1990s that Gauteng province might turn the building into a high-rise prison but, despite the decay, Ponte City was home in this period to many migrants, especially from Francophone West and Central Africa.[3][10]

New Ponte

editIn May 2007, Ponte changed ownership and a re-development project, "New Ponte", was put in motion. David Selvan and Nour Addine Ayyoub under Ayyoub's company, Investagain, planned to revitalise the building completely.[11] The planned development would have contained 467 residential units, retail and leisure-time areas. Over the next few years, the Johannesburg Development Agency planned to invest about R900 million in the areas around Ponte City such as the Ellis Park Precinct project as well as an upgrade of Hillbrow and Berea partly in preparation for the 2010 FIFA World Cup.

The subprime mortgage crisis caused the banks not to provide the funding required to finish the revitalisation. The project was cancelled and ownership was given back to the Kempston Group, which continued to market the building.[11] [1]

Current status

editAs of 2017, the building had been totally refurbished, and had become "desirable" and "affordable", at least in the terms promoted by the Kempston Group. The population was reported to be approximately 80% black, and to include immigrants from various countries.[12] As of 2022, despite problems with infrastructure and governance in central Johannesburg, Kempston was promoting its "safe and affordable" apartments.[2]

In photography, film, and literature

editPhotographers have been drawn to Ponte City since its inception, beginning with world-renowned David Goldblatt, who worked in the inner city from 1948 to the 21st century.[13] South African photographer Mikhael Subotzky and British artist Patrick Waterhouse won the Discovery award at the Rencontres d'Arles photography festival in 2011 for their three-year project "Ponte City", published in 2014.[14][15]

Especially in the edgy 1990s, in the awkward and dangerous transition from the late-apartheid 1980s to the attempts by the Johannesburgt Development Agency to clean up the inner city from 2002, Ponte City appeared in dark, dystopian films, such as Dangerous Ground (1997) by South African director Darrell Roodt, starring U.S. rapper Ice Cube. One of the final shots of District 9 (2009) by South African expatriate Neill Blomkamp features the tower.[16] A battle scene was filmed inside the tower for the 2016 movie Resident Evil: The Final Chapter.[17] More nuanced treatments include The Foreigner (1997), an evocative short by Zola Maseko about a Senegalese migrant living in Pone City, which opens with a night-time shot taken from a helicopter of the neon Coca Cola ad that wrapped around the top of the building at that time. Director Philip Bloom dedicated a documentary film titled Ponte Tower.[18] Ingrid Martens filmed the documentary Africa Shafted: Under one Roof, entirely, over two and a half years, in the Ponte lifts.[19]

Ponte City also features in post-apartheid literature. Although set in the next-door district of Hillbrow, Phaswane Mpe's novel Welcome to our Hillbrow (2001) alludes to the tower. German writer Norman Ohler used the Ponte as the setting for his book Stadt des Goldes ("City of Gold"), published in South Africa under the title Ponte City, saying "Ponte sums up all the hope, all the wrong ideas of modernism, all the decay, all the craziness of the city. It is a symbolic building, a sort of white whale, it is concrete fear, the tower of Babel, and yet it is strangely beautiful".[20][21] [22]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Pampalone, Tanya (2009). "The Full Ponte". Maverick. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Ponte City Apartments". Emporis. 2009. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d Davie (9 November 2007). "Ponte: revival of a Joburg icon". pub. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ Chipkin, Clive, Johannesburg in Transition, STE Publishers, 2008

- ^ Editors note in Housing in Southern Africa, 2006, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d Hanes, Stephanie (12 February 2008). "Ponte City – a South African landmark – rises again". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ Kruger, Loren (2013). Imagining the Edgy City: Writing, Performing and Building Johannesburg. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780199321902.

- ^ Chipkin, Clive (1998). "The great apartheid building boom: The Transformation of Johannesburg in the 1960s." In blank_____: Architecture, Apartheid and After. Ed. Hilton Judin and Ivan Vladislavić. Rotterdam: NAi (National Architecture Institute): 249-67

- ^ Smith, David (11 May 2015). "Johannesburg's Ponte City: 'the tallest and grandest urban slum in the world' – a history of cities in 50 buildings, day 33". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ Mda, Lizeka (1998) "City Quarters". In blank___: Architecture, Apartheid and After. Ed. Hilton Judin and Ivan Vladislavić. Rotterdam: NAi (National Architecture Institute): 196-201

- ^ a b Pampalone, Tania (16 December 2008). "Ponte project crashes". Mail & Guardian Online. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ 'The building creaks and sways': life in a skyscraper

- ^ Goldblatt, David (2010). TJ--Johannesburg Photographs 1948-2010. Rome: Contrasto. ISBN 9788869652721.

- ^ Subotzky, Mikhael; Waterhouse, Patrick (2014). Vladislavić, Ivan (ed.). Ponte City. Munich: Steidl. ISBN 9783869307503.

- ^ Sean O'Hagan, "Tower blocks and tomes dominate the Rencontres d'Arles", The Guardian, 11 July 2011.

- ^ Sailer, Steve (21 August 2009). "Neill Blomkamp's Giant Apartheid Metaphor". iSteve.com. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ^ Lenora Brown, Ryan (21 February 2017). "The South African Building That Came to Symbolize the Apocalypse". The Atlantic.

- ^ Bloom, Philip (12 October 2012), Ponte Tower, retrieved 17 September 2018

- ^ "I'M Original | Media that Matters". I'M Original | Media that Matters. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ Mpe, Phaswane (2001). Welcome to our Hillbrow. Scottsville, South Africa: University of KwaZulu Natal Press. ISBN 9780869809952.

- ^ Ohler, Norman (2002). Stadt des Goldes (in German) (1 April 2002 ed.). Rowohlt Tb. ISBN 3-499-22727-4.- Total pages: 253

- ^ Ohler, Norman (2003). Ponte City. Cape Town: David Phillip. ISBN 9780864866295.

External links

edit- More photos of the Ponte Tower

- Photographs of Bertrand Goldberg's Marina City