Polacanthinae is a subfamily of ankylosaurs, most often nodosaurids, from the Late Jurassic through Early Cretaceous of Europe and potentially North America and Asia. The group is defined as the largest clade closer to Polacanthus foxii than Nodosaurus textilis or Ankylosaurus magniventris, as long as that group nests within either Nodosauridae or Ankylosauridae. If Polacanthus, and by extent Polacanthinae, falls outside either family-level clade, then the -inae suffix would be inappropriate, and the proper name for the group would be the informally defined Polacanthidae.[1]

| Polacanthines Temporal range: Late Jurassic - Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

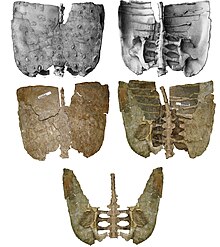

| Pelvis of Polacanthus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Clade: | †Ankylosauria |

| Family: | †Nodosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Polacanthinae Lapparent & Lavocat, 1955 |

| Genera | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Polacanthines were somewhat more lightly armoured than more advanced ankylosaurids and nodosaurids. Their spikes were made up of thin, compact bone with less reinforcing collagen than in the heavily armoured nodosaurids. The relative fragility of polacanthine armour suggests that it may have been as much for display as defense.[2] They appear to have become extinct about the same time a land bridge opened between Asia and North America.[3]

Classification edit

The family Polacanthidae was named by Ernst Jaekel in 1910 to refer to a group of ankylosaurs which seemed to him intermediate between the ankylosaurids and nodosaurids. This grouping was ignored by most researchers until the late 1990s, when it was used as a subfamily (Polacanthinae) by Kirkland for a natural group recovered by his 1998 analysis suggesting that Polacanthus, Gastonia, and Mymoorapelta were closely related within the family Ankylosauridae, and he additionally referred Hoplitosaurus and Hylaeosaurus to the subfamily, though they were too incomplete to analyze.[4] Kenneth Carpenter resurrected the name Polacanthidae for a similar group which he also found to be closer to ankylosaurids than to nodosaurids. Carpenter became the first to define Polacanthidae as all dinosaurs closer to Gastonia than to either Edmontonia or Euoplocephalus.[5] Most subsequent researchers placed polacanthines as primitive ankylosaurids, though mostly without any rigorous study to demonstrate this idea. The first comprehensive study of 'polacanthid' relationships, published in 2011, found that they are either an unnatural grouping of primitive nodosaurids, or a valid subfamily at the base of Nodosauridae.[6] In the act of formally defining Polacanthinae in line with the requirements of the PhyloCode, Madzia and colleagues chose for the analysis of Yang et al. (2013) to be the primary reference for Polacanthinae, supplemented by similar results found by Kirkland (1998), Thompson et al. (2012), Arbour et al. (2016), Rivera-Sylva et al. (2018), and Zheng et al. (2018).[1][7][4][6][8][9][10]

| Nodosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

While the clade is frequently referenced in literature, a majority of taxa considered to be polacanthines have instead been found to not form any natural groups with Polacanthus, representing both primitive nodosaurids, primitive ankylosaurids, or outside the Nodosauridae-Ankylosauridae clade.[1] In the analysis of Arbour et al. in 2016, and its subsequent modifications by Rivera-Sylva et al. and Zheng et al. in 2018, only Hoplitosaurus was resolved as a polacanthine alongside Polacanthus, with Peloroplites and Taohelong falling within Nodosaurinae, Gargoyleosaurus, Gastonia, and Mymoorapelta being more basal nodosaurids outside both subclades, and Hylaeosaurus representing an early-diverging ankylosaurid.[8][9][10]

References edit

- ^ a b c d Madzia, D.; Arbour, V.M.; Boyd, C.A.; Farke, A.A.; Cruzado-Caballero, P.; Evans, D.C. (2021). "The phylogenetic nomenclature of ornithischian dinosaurs". PeerJ. 9: e12362. doi:10.7717/peerj.12362. PMC 8667728. PMID 34966571.

- ^ Hayashi, S.; Carpenter, K.; Scheyer, T.M.; Watabe, M.; Suzuki, D. (2010). "Function and evolution of ankylosaur dermal armor" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 55 (2): 213–228. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0103.

- ^ Kirkland, J. I. (1996). Biogeography of western North America's mid-Cretaceous faunas - losing European ties and the first great Asian-North American interchange. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 16 (Suppl. to 3): 45A.

- ^ a b Kirkland, J.I. (1998). "A polacanthine ankylosaur (Ornithischia: Dinosauria) from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) of eastern Utah". In Lucas, S.G.; Kirkland, J.I.; Estep, J.W. (eds.). Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. Vol. 14. pp. 271–281.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Carpenter K (2001). "Phylogenetic analysis of the Ankylosauria". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 455–484. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

- ^ a b Thompson, R.S.; Parish, J.C.; Maidment, S.C.R.; Barrett, P.M. (2012). "Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 301–312. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.569091.

- ^ Yang, J.; You, H.; Li, D.; Kong, D. (2013). "First discovery of polacanthine ankylosaur dinosaur in Asia". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 51 (4): 265–277.

- ^ a b Arbour, V.M.; Zanno, L.E.; Gates, T. (2016). "Ankylosaurian dinosaur palaeoenvironmental associations were influenced by extirpation, sea-level fluctuation, and geodispersal". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 449: 289–299. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.02.033.

- ^ a b Rivera-Sylva, H.E.; Frey, E.; Stinnesbeck, W.; Carbot-Chanona, G.; Sanchez-Uribe, I.E.; Guzmán-Gutiérrez, J.R. (2018). "Paleodiversity of Late Cretaceous Ankylosauria from Mexico and their phylogenetic significance". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 137: 83–93. doi:10.1007/s13358-018-0153-1.

- ^ a b Zheng, W.; Jin, X.; Azuma, Y.; Wang, Q.; Miyata, K.; Xu, X. (2018). "The most basal ankylosaurine dinosaur from the Albian–Cenomanian of China, with implications for the evolution of the tail club". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 3711. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-21924-7. PMC 5829254. PMID 29487376.