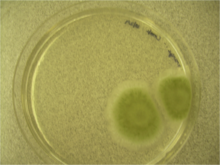

Penicillium expansum is a psychrophilic blue mold that is common throughout the world in soil.[1] It causes Blue Mold of apples, one of the most prevalent and economically damaging post-harvest diseases of apples.

| Penicillium expansum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Order: | Eurotiales |

| Family: | Aspergillaceae |

| Genus: | Penicillium |

| Species: | P. expansum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Penicillium expansum Link, (1809)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Though primarily known as a disease of apples, this plant pathogen can infect a wide range of hosts, including pears, strawberries, tomatoes, corn, and rice. Penicillium expansum produces the carcinogenic metabolite patulin, a neurotoxin that is harmful when consumed.[2] Patulin is produced by the fungus as a virulence factor as it infects the host. Patulin levels in foods are regulated by the governments of many developed countries. Patulin is a particular health concern for young children, who are often heavy consumers of apple products. The fungus can also produce the mycotoxin citrinin.

Hosts and disease development

editPenicillium expansum has a wide host range, causing similar symptoms on fruits which include apples, pears, cherries, and citrus .[3] Initial infection most often occurs at sites of fruit injury, such as bruises or puncture wounds.[4] Although infections may start in the field, infected spots often become evident post-harvest, and expand while fruit is in storage.[4] Infected areas are clearly delineated and light brown, and soft decaying tissue can be easily "scooped" out of the surrounding healthy tissue.,[4][1]

Spore masses later appear on the surfaces of infected fruit, initially appearing as white mycelium, then turning blue to blue-green in color as the asexual spores mature.[1] Fruit affected by P. expansum typically has an earthy, musty odor.[4] Lesions measure 1–1.25 inches in diameter eight to ten weeks after infection if kept under cold storage conditions.[1] Age factors into P. expansum infection, in that overripe or mature fruits are most susceptible to infection, while those picked underripe are less likely to become infected.

In apples, the colors of the lesions may vary with variety, from lighter-brown on green and yellow apple varieties to dark-brown on the deeper-red and other darker-color varieties.[1] Varieties particularly susceptible to P. expansum infection include McIntosh, Golden Supreme, and Golden Delicious.[5][6]

Both sweet and sour cherries are affected by P. expansum. Cherry varieties found to be particularly susceptible to P. expansum infection were mainly early varieties, including Navalinda and Burlat.[7]

Diagnosis

editPenicillium expansum can be identified by its morphological characteristics and secondary metabolites in fruit or in axenic culture.[8] The presence of the secondary metabolite patulin can suggest P. expansum infection, but this method is not species-specific as a number of different Penicillium species and their allies produce patulin. Patulin presence can be assayed using high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection.[9] Molecular methods based on species-specific genes can speed identification.[10][11][12]

Environment

editPenicillium expansum grows best in wet, cool (<25C) conditions.[13] P. expansum was found to grow most efficiently in a temperature range of 15–27 degrees Celsius, with slower growth at lower and higher temperatures.[13] P. expansum grows best in wet conditions; growth rate was fastest at a relative humidity of 90%.[13] P. expansum infection acidifies host tissues via the secretion of organic acids, and that acidification enhances fungal development, indicating a link between environmental acidity and P. expansum virulence.[14]

Disease cycle

editP. expansum infects a fruit via wounds through which the conidia are able to enter.[15] Usually, puncturing, bruising, and limb rubs occur during harvesting, packaging, and processing of the fruit, all of which provide sites through which spores can enter the fruit. Conidia can be found in soil, decaying debris, and tree bark, and can survive cold temperatures. Conidia may be isolated from the air of the orchard and packaging house, on the walls of the packaging houses, and from the water and fungicide solution into which harvested fruits are dunked before packaging or storage. Exposure to conidia at any step of growth, harvesting, processing, shipping, and storage can lead to inoculation and disease. Conidia that have gained access via a wound can germinate to form a germ tube. This germ tube will continue to grow as hyphae which colonize the fruit, killing fruit cells in an expanding infection.

If the fungus has colonized the fruit with mycelium, the formation of conidiophores occurs on the surface or subsurface of the hyphae. The conidiophores are mostly smooth-walled terverticillate penicilli. A terverticillate pencilii has multiple branch points below the phialides, the cells that the conidia are attached to. However, at times, the penicilli may be rough or biverticillate (only two levels of branching).[16] The phialides are packed close together with nearly a cylindrical shape.[17] The conidia are dry, smooth, elliptical, and "dull-green" in color and are often disseminated by wind currents.

Sexual reproduction has not been observed in nature for P. expansum.[18]

Management

editDue to the susceptibility to infection of mature and overripe fruit, post-harvest treatment of fruit with fungicides is the most common method of combating P. expansum. Proper sanitation and careful handling of the fruit are two non-chemical methods that can help control the disease. Good sanitation reduces contact with orchard soil either on the fruit or in transportation containers. And since the fungus needs a wound to infect, careful handling can reduce infection even when the fungus is present. Chemical treatment with a chlorine bath can be effective in killing spores. Biofungicides using active ingredients such as bacteria and yeast have been successful in preventing infection but are ineffective against existing infections.[4]

Importance

editPenicillium expansum produces the mycotoxin patulin, a neurotoxin that can enter the food supply via apples and apple products such as juice and cider.[19] Considering the size of the apple product industry and the large number of people that may come into contact with infected fruits, control of P. expansum is vitally important.[20]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Janisiewicz, Wojciech. "Blue Mold". USDA Appilachian Fruit Research Station. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Morales H, Marín S, Rovira A, Ramos AJ, Sanchis V (January 2007). "Patulin accumulation in apples by Penicillium expansum during postharvest stages". Lett Appl Microbiol. 44 (1): 30–5. doi:10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.02035.x. PMID 17209811. S2CID 5764456.

- ^ Ashizawa, Eunice C. (October 2000). "Fungistatic composition and a fungistatic method utilizing the composition". Gencor International inc. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Blue Mold". Washington State university. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Konstantinou, S.; Karaoglanidis, G.S.; Bardas, G.A.; Minas, I.S.; Doukas, E.; Markoglou, A.N. (2011). "Post harvest fruit rots of apple in Greece:Pathogen incidence and relationships between fruit quality parameters, cultivar susceptibility and patulin production". Plant Disease. 95 (6): 666–672. doi:10.1094/pdis-11-10-0856. PMID 30731903.

- ^ "Improving the safety of apple juice and cider". Cornell University CALS department. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Hui, Y.H. (2006). Handbook of Fruits and Fruit Processing. Blackwell. p. 697. ISBN 9780470276488.

- ^ Pianzzola, M.J; M.Muscatelli, S.Vero (January 2004). "Characterization of Penicillium isolates associated with blue mold on apple in Uruguay" (PDF). Plant Disease. 88 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1094/pdis.2004.88.1.23. PMID 30812451. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Patulin in Apple Juice". Horticultural Development Company. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ Marek, Patrick; Thirunauukkarasu, Annamalai; Kumar, Venkitanarayanan (31 December 2003). "Detection of Penicillium expansum by polymerase chain reaction". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 89 (2–3): 139–144. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00115-6. PMID 14623379.

- ^ Dombrink-Kurtzman, Mary Ann; Amy E. McGovern (June 2007). "Species-specific identification of penicillium linked to patulin contamination" (PDF). Journal of Food Protection. 70 (11): 2646–50. doi:10.4315/0362-028X-70.11.2646. PMID 18044450.

- ^ Oliveri, C.; A.Campisano; A.Catara; G. Cirvilleri (2007). "Characterization and fAFLP genotyping of Penicillium strains from postharvest samples and packinghouses". Plant Pathology. 89 (1): 29–40. doi:10.4454/jpp.v89i1.721 (inactive 31 January 2024). JSTOR 41998354.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - ^ a b c Larous, L.; Handel, N.; Abood, J.K.; Ghoul, M. (2007). "The growth and production of patulin mycotoxin by penicillium expansum on apple fruits and its control by the use of propionic acid and sodium benzoate". Department of Biology, College of Science, University of Setiff. Setiff, Algeria.

- ^ Prusky, Dov; McEvoy, L. James; Saftner, Robert; Conway, S. William; Jones, Richard (2004). "Relationship Between Host Acidification and Virulence in Penicillium spp. on Apple and Citrus Fruit". Phytopathology. 94 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.1.44. PMID 18943818.

- ^ Torres, R; Teixidó, N.; Viñas, I.; Mari, M.; Casalini, L.; Giraud, M.; Usall, J (November 2006). "Efficacy of Candida sake CPA-1 Formulation for Controlling Penicillium expansum Decay on Pome Fruit from Different Mediterranean Regions". Journal of Food Protection. 69 (11): 2703–11. doi:10.4315/0362-028X-69.11.2703. PMID 17133815. S2CID 45025141.

- ^ Frisvad, Jens; Samson, Robert (2004). "Polyphasic taxonomy of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium" (PDF). Studies in Mycology. 49: C174.

- ^ Pitt, John (1985). Fungi and Food Spoilage. Academic Press. pp. 1–413. ISBN 978-0125577304.

- ^ Sapers, Gerald M. (2006). Microbiology Of Fruits And Vegetables. CRC Press. pp. 634. ISBN 978-0849322617.

- ^ Deacon, J.W. (1997). Modern Mycology. Blackwell Science Inc. pp. 118, 122, 132, 206, 228, 231. ISBN 978-0-632-03077-4.

- ^ David A. Rosenberger; Catherine A. Engle; Frederick W. Meyer; Christopher B. Watkins (2006). "Penicillium expansum Invades Apples Through Stems during Controlled Atmosphere Storage". Plant Health Progress. 7 (1). American Phytopathological Society. doi:10.1094/PHP-2006-1213-01-RS.