The Paus family (pronounced [ˈpæʉs]) is a prominent Norwegian family with a long history of involvement in the clergy, nobility, industry, and the arts. The family first emerged as members of the elite of 16th-century Oslo and, for centuries, belonged to Norway's "aristocracy of officials," especially in the clergy and legal professions in Upper Telemark. Later generations became involved in shipping, steel, and banking. The family is particularly known for its close association with Henrik Ibsen,[1][2] and for modern members like the singer Ole Paus.

| Paus | |

|---|---|

| |

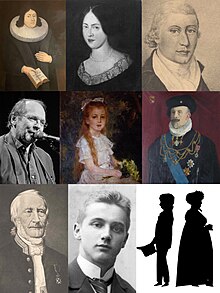

Family members from the 17th to the 21st centuries: priest Hans Paus; Aase Paus; shipowner Ole Paus; singer Ole Paus; Helvig Paus; count Christopher Paus; governor Christian Cornelius Paus; lawyer and mountaineer George Wegner Paus; lawyer Henrik Johan Paus and Hedevig Paus (Ibsen's grandmother) | |

| Current region | Norway, Sweden, Denmark, United Kingdom, Switzerland |

| Earlier spellings | Pausius (Latinized), de Paus (internationally), von Paus (Austria only) |

| Etymology | from Middle Saxon/Middle Dutch paus, paues, pauwes, "pope", perhaps applied as a nickname for someone renowned for his piety |

| Place of origin | Known in Oslo, Norway since the 16th century |

Two brothers from Oslo who both became priests, Hans (1587–1648) and Peder Povelsson Paus (1590–1653), have long been known as the family's earliest certain ancestors. In his book Slekten Paus, S.H. Finne-Grønn traced the family two further generations back, to Hans Olufsson (died 1570), a high-ranking member of the royal clergy who held the rank of a knight, the highest rank of nobility in Norway at the time.[3][4] The name Paus, believed to be of Middle Saxon or Middle Dutch origin,[5] is known in Oslo since the 14th century, notably as the name of the Lawspeaker of Oslo Nikolas Paus (mentioned 1329–1347) and as the name of one of medieval Oslo's "city farms", Pausinn (mentioned 1324–1482). The extant family is descended from Peder Povelsson Paus, who was provost of Upper Telemark from 1633. From the 17th to the 19th century, the family were among the foremost of the regional elite, the "aristocracy of officials" in Upper Telemark,[1] where many family members served as priests of the state church, judges and other government officials and where several state and church offices in practice were hereditary in the family for extended periods. For example, the office of governor/chief district judge (sorenskriver) of Upper Telemark—the region's senior government official—was continuously held by the family for 106 years (1668–1774) and passed on in an hereditary manner.

From the late 18th century family members successively established themselves as ship's captains, shipowners, wealthy merchants and bankers in the port towns of Skien and Drammen. From the 19th century several family members were prominent as steel industrialists in Christiania; other family members founded the industrial company Paus & Paus in Drammen and Oslo. Family members have also owned or co-owned several other major companies, including Norway's largest shipping company Wilh. Wilhelmsen. Since the early 20th century family members have owned half a dozen estates and castles in Sweden, of which the estates Herresta and Näsbyholm in Södermanland are still owned by the family; the Herresta/Näsbyholm branch is descended from Tatiana Tolstoy-Paus, Leo Tolstoy's last surviving grandchild. Christopher Paus, a papal chamberlain and heir to one of Norway's largest timber companies who donated the Paus collection of classical sculpture to the National Gallery, was conferred the title of count by Pope Pius XI in 1923. A village in India, Pauspur, was named in honour of the family in the 19th century. Family members living in Italy and Austria-Hungary from the 19th century spelled the name de Paus or von Paus.[a]

The family's best known descendant is the playwright Henrik Ibsen. Both of his parents belonged to the family in either a biological or social sense. Through the Paus family, their closest relatives, Ibsen's parents had been raised as "near-siblings."[b] Ibsen named or modelled various characters after family members. Episodes and motifs in several of Ibsen's dramas—notably Peer Gynt, Ghosts, An Enemy of the People, The Wild Duck, Rosmersholm, and Hedda Gabler—were inspired by Paus family traditions and real events that took place in the closely intertwined households of the siblings Ole Paus and Hedevig Paus in the early 19th century. The Paus family figures in Ibsen studies, and Jon Nygaard has argued that the emergence of "the new Puritan state of the officials" with the spirit of "Upper Telemark, the Paus family" is a major theme in Ibsen's work.[7] Modern family members include the troubadour Ole Paus and his son, the composer Marcus Paus. Family members live in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, the U.K. and Switzerland. In the course of its history, family members have used multiple seals and coats of arms, including a crane in its vigilance in the seal of Povel Paus on the 1661 Sovereignty Act and a bull's head with golden star used since the 19th century.

The name Paus in Oslo in the 14th and 15th centuries

editThe name Paus is known in Oslo in the 14th and 15th centuries and was used by individuals who belonged to the same small elite social class as the family that is documented from the 16th century. The farm Pausinn ("The Paus") was one of the "city farms" that were part of medieval Oslo and is mentioned between 1324 and 1482, when it was owned by individuals who belonged to the city's elite. Paus is also used as the cognomen of several individuals in 14th and 15th century Oslo or its surroundings who appear to be related and who owned substantial property in nearby Nes. The most notable individual named Paus in medieval Oslo was Nikolas Sigurdsson Paus, who is mentioned as the Lawspeaker of Oslo in 1347, shortly before the Black Death reached the city. There were around a dozen lawspeakers in the entire kingdom, and they were part of the nobility. Two seals used by Nikolas Paus are included in the Encyclopedia of Noble Families in Denmark, Norway and the Duchies (published 1782–1813).[8] Medieval historians P.A. Munch, Alexander Bugge and Edvard Bull argued that Pausinn was probably named after Nikolas Paus or a member of his family; on the basis of the Middle Saxon/Middle Dutch-sounding name, they argued that the family was of Low German/Dutch origin, and wrote that the Paus family was an influential immigrant family in medieval Oslo; the family may have immigrated as merchants in the 12th or 13th century from northern Germany or the Netherlands.[9][10][11]

Genealogist S.H. Finne-Grønn presumed that the younger family's name was derived from the name of Nikolas Paus and his family and from the city farm of Pausinn in one way or the other; only a century separates the last mention of Pausinn and the birth of the modern family's earliest certain ancestors who were known by the name.[4] Oslo had a very small population in the time period, probably less than a thousand inhabitants in the years following the Black Death, and an even smaller elite, that family names were exceedingly rare in Norway both in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries and typically only used by nobles/clerics and merchants of an immigrant background, and that the name Paus is atypical of Norwegian. Genealogist C. S. Schilbred noted that "the connection between the older and the younger family of the name has not been established, but on the other hand no convincing arguments against such a possibility have been made."[12] It is however a possibility that the family acquired the name indirectly, e.g. from Pausinn, rather than by direct descent. The modern family, believing itself to be related to the 14th century family, adopted an interpretation (itself dating to the 18th century) of Nikolas Paus' 1330 seal as its coat of arms in the late 19th century.[13]

The family in the 16th century

editAccording to genealogist S.H. Finne-Grønn, the family is most likely descended from Hans Olufsson (died 1570), a canon at St Mary's Church, the royal chapel in Oslo.[3][4] As indicated by his patronymic, Hans Olufsson's father was named Oluf. Due to his career as a member of the royal clergy, Hans Olufsson almost certainly had a privileged family background. Most canons in Norway at the time were recruited from the lower nobility, and normally studied at universities abroad, which was normally only possible with an affluent background. Hans Olufsson served as a canon at St Mary's Church and a member of its cathedral chapter until it was merged with that of Oslo Cathedral in 1545, following the Reformation. St Mary's Church was a powerful political institution as the seat of government of Norway at the time, as its provost was also the Chancellor of Norway with one of the canons serving as Vice-Chancellor. Its clergy held high aristocratic rank ex officio, as decreed by Haakon V of Norway in a 1300 royal proclamation, with canons holding the rank of Knight[14] (the highest rank of nobility in Norway since 1308), and were granted significant privileges. Hans Olufsson held a prebend (estate held for his lifetime), the prebend of Saint Mary's altar sub lectorio, also known as the prebend of Dillevik,[15] that included the income of 43 church properties (36 huder, hides) in Eastern Norway. After 1545, Hans Olufsson served as a priest at Oslo Cathedral, but retained his prebend affiliated with the estate of St Mary's Church. He died on the night between 17 and 18 September 1570 and was buried in Oslo Cathedral on 19 September. Following his death, his prebend passed to Jens Nilssøn, the noted Oslo humanist and later Bishop of Oslo.[4]

Hans Olufsson's son, as documented by court proceedings from 1602, was Povel Hansson (probably born ca. 1545–50), who was a burgher and apparently a wealthy merchant in Oslo. He was according to Finne-Grønn[4] most likely the father of the two clergymen who became the ancestors of two lineages of the family, and who have long been known as the family's earliest certain ancestors: Hans Povelsson Paus (1587–1648) and Peder Povelsson Paus (1590–1653). Both brothers were born in Oslo in the late 16th century and clearly belonged to its social elite, evidenced by their extensive and costly education, their subsequent careers and their apparent social connections to prominent men of the church and nobility in Oslo in the early 17th century.

Hans and Peder Povelsson Paus and their descendants

editHans Povelsson Paus (1587–1648) was born in Oslo and entered the University of Copenhagen as a student under the name Johannes Paulli Asloensis (Asloensis meaning Oslo) around 1607–08. He earned the bachelor's degree in 1616, and shortly after became a chaplain at Oslo Cathedral. In 1622, he succeeded his presumed stepfather Anders Augustinusen as parish priest in Fredrikstad. He had a limited number of descendants, including his sons, Magister Povel Hansson Paus (1620–1658), parish priest in Lier, Bragernes and Strømsø, and Anders Hansson Paus (1622–1689), parish priest in Jevnaker.[4]

Hans' younger brother Peder Povelsson Paus (1590–1653) was born in Oslo and entered the University of Copenhagen as a student under the name Petrus Paulli Asloensis. Following his studies, he served as headmaster of Skien Latin School around 1617, as parish priest in Vinje and as parish priest in Kviteseid and provost of Upper Telemark from 1633. He was married to Johanne Madsdatter. The tradition of Peder's great physical powers have been handed down in Kviteseid until the modern age. Peder was buried under the choir floor in Kviteseid Old Church, where his son Povel placed a beautiful poem in Latin in memory of his father.[4]

Peder's son Povel Pedersson Paus (1625–1682) was parish priest in Hjartdal and married to Ingrid Corneliusdatter Trinepol (1632–1694), a daughter of timber merchant Cornelius Jansen Trinepol (1611–1678) and a member of the wealthy patriciate of Skien who was notably descended from Jørgen von Ansbach. Povel Pedersson Paus was among the 87 representatives of the Norwegian clerical estate who signed the 1661 Sovereignty Act, Denmark-Norway's new constitution which introduced absolute and hereditary monarchy.[16] Magnus Brostrup Landstad describes Povel Pedersson Paus as a learned and pious priest who held on to Catholic customs in post-Reformation Norway.[17] Well versed in Latin, he wrote a Latin poem about his father and personally educated his children. Among his ten children were parish priest in Kviteseid Hans Paus (1656–1715) and district judge in Upper Telemark Cornelius Paus (1662–1723), from which two living main lines of the family are descended.[18] During the 17th and 18th centuries, the office of district judge of Upper Telemark was effectively hereditary in the family for 106 consecutive years and four generations.[19]

Skien branch

editThe Skien branch of the family is descended from district judge of Upper Telemark Cornelius Paus (1662–1723). He married Valborg Ravn (1673–1726), the daughter of his predecessor as district judge Jørgen Hansen Ravn and Margrethe Fredriksdatter Blom (born 1650). His father-in-law was appointed district judge in 1668 and stepped down in favour of his son-in-law in 1696.[19]

Their son, the procurator (i.e. advocate) Paul Paus (1697–1768) served as his father's deputy judge and as acting district judge for some time, and married Martha Blom (1699–1755), a daughter of forest owner Christopher Blom (1651–1735) and Johanne Margrethe Ørn (1671–1745).[20]

They were the parents of Johanne Paus (1723–1807), married to provost of Raabyggelaget Johan Christopher von Koss (1725–1778), forest inspector of Upper Telemark Cornelius Paus (1726–1799), and Cathrine (Medea Maj) Paus (1741–1776), married to Counselor of Justice Anthon Jacob de Coucheron (1732–1802).

Cornelius Paus sold the former district judge's farm Haatvet in Lårdal in 1788 and moved to Skien, where he died in the home of his son-in-law Johan Andreas Altenburg in 1799. He was married to Christine Falck and was the father of Ole, Martha and Hedevig Paus, who all settled in Skien.

Martha Paus (1761–1786) married ship-owner and timber merchant Hans Jensen Blom (1757–1808), and her descendants include supreme court justice Knut Blom.

Hedevig Christine Paus (1763–1848) married ship-owner and merchant Johan Andreas Altenburg, and they were the maternal grandparents of playwright Henrik Ibsen. Among their descendants are also Prime Minister Sigurd Ibsen, film director Tancred Ibsen and the actress Beate Bille.

Ole Paus (1776–1855) became a burgher of Skien in 1798, and has numerous descendants. He married Johanne Plesner, daughter of the wealthy merchant Knud Plesner and Maria Kall, and who had formerly been married to ship's captain Henrich Ibsen (Henrik Ibsen's grandfather). Ole Paus and Johanne Plesner were the parents of the lawyer Henrik Johan Paus (1799–1893), of the judge, magistrate, Member of Parliament and Governor of Bratsberg Christian Cornelius Paus (1800–1879), and of the merchant and ship-owner Christopher Blom Paus (1810–1898). Ole Paus also became the stepfather of Knud Ibsen. As Henrik Ibsen pointed out in an 1882 letter to Georg Brandes, the Paus family was one of the patrician families dominating the port town of Skien, where he grew up.[21][22]

Henrik Johan Paus, a lawyer who owned the estate Østerhaug in Elverum for some years, married Sophie Lintrup, a daughter of county chief physician (amtsfysikus) Christian Lintrup. They were the parents of Major and War Commissioner Johan Altenborg Paus (1833–1894), who married his second cousin Agnes Tostrup, a daughter of timber merchant Christopher Tostrup. They were the parents of land owner, art collector, philanthropist, papal chamberlain and Knight of Malta Christopher Tostrup Paus (1862–1943), who inherited much of his family's shares of the Tostrup & Mathiesen company and who owned the Trystorp and Herresta estates in Sweden. A convert to Catholicism, Christopher Tostrup Paus was conferred the hereditary title of count by Pope Pius XI on 25 May 1923, and joined the Ointroducerad Adels Förening in 1924, thus becoming part of Sweden's unintroduced nobility.[23] He died in 1943 without issue. Among Henrik Johan Paus' descendants are also the British diplomat Christopher Lintrup Paus (b. 1881), the Director at the Directorate of Public Roads Hans Wangensten Paus (b. 1891) and Ambassador in Iran, Brazil and Mexico Thorleif Lintrup Paus (b. 1912).

Christopher Blom Paus was the father of iron and steel wholesaler, factory-owner and banker Ole Paus (1846–1931) and engineer Carl Ludvig Paus (1856–1953).

Ole Paus was married to Birgitte Halvordine Schou (a cousin of Halvor Schou), and their children were Martha Marie Paus (b. 1876), married to historian Otto von Munthe af Morgenstierne, businessman Christopher Blom Paus (1878–1959), Consul-General, businessman and estate owner Thorleif Paus (1881–1976), Else Margrethe Paus (b. 1885), married to businessman Nicolay Nissen Paus (her distant relative), and Fanny Paus (1888–1971), married to businessman Trygve Andvord (1888–1958).

Christopher Blom Paus (b. 1878) was the father of businessman Per Christian Cornelius Paus, married to his distant cousin Hedevig, Countess of Wedel-Jarlsberg, who owned the Esviken manor, and Else Birgitte Paus, married to Danish lawyer and papal chamberlain Gunnar Garth-Grüner (1903–93). Per and Hedevig were the parents of Cornelia Paus, businessman Peder Nicolas Paus and businessman Christopher Paus, married to Cecilie Wilhelmsen, whose family owns the Wilh. Wilhelmsen shipping company. Their daughters are designer Pontine Paus and Olympia Paus; Pontine is the girlfriend of the chairman of Sotheby's, Harry Primrose, Lord Dalmeny, the heir to the Earldom of Rosebery, while Olympia is married to former Cambridge Analytica CEO Alexander Nix.

Thorleif Paus served as Norwegian consul-general in Vienna, owned two factories and became owner of Kvesarum Castle in Sweden. He was married to Ella Stein and secondly to Countess Ella Moltke née Glückstadt. He was the father of Major-General Ole Otto Paus, the grandfather of troubadour Ole Paus and the great-grandfather of composer Marcus Paus. Else and Nicolay Nissen Paus were the parents of Lucie Paus, married to land-owner Axel Løvenskiold, and Fanny Paus, married to Ambassador Henrik Andreas Broch.

Herresta branch

editCarl Ludvig Paus (b. 1856) was the father of land-owner Herman Christopher Paus (1897–1983), who bought Herresta, one of the largest estates of Södermanland County in Sweden, from his relative, Count Christopher Tostrup Paus, in 1938. He was married to Countess Tatyana Tolstoy, a granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy. Their descendants own several estates in Sweden and form the Herresta branch of the family. Today, Herresta is managed by their grandson Fredric Christopherson Paus.

Christopher Tostrup Paus owned many family portraits dating back to the 17th century, which were found at Herresta and some of which are still found there. They included a silhouette of members of the Altenburg and Paus families from shortly after the Napoleonic Wars, including Marichen Altenburg—the only existing portrait of any of Henrik Ibsen's parents.

Drammen branch

editThe Drammen branch is descended from Hans Paus (b. 1656). He was married to Susanne Morland (1670–1747), who was the daughter of provost of Upper Telemark Amund Morland (1624–1700) and the granddaughter of land-owners Christen Andersen and Anne Gundersdatter, who owned Borgestad Manor. Hans Paus wrote the poem Stolt Anne about his wife's first cousin Anne Clausdatter, which is noted for being the first written in dialect in Norway. Their son Peder Paus (1691–1759) succeeded his uncle Cornelius as district judge of Upper Telemark in 1723, and was in turn succeeded by his son, Hans Paus (1720–1774) in 1751. Peder Paus was married in his first marriage to Danish-born Cathrine Medea May Hermansdatter Arentsen (died 1736), daughter of the parish priest in Ølsted northwest of Copenhagen Herman Arentsen and granddaughter of Arent Berntsen and Søren Nielsen May.[25] In his second marriage, he married his cousin Hedvig Coldevin Corneliusdatter Paus. Hans Paus, a son of the first marriage, was married to Danish-born Andrea Jaspara Nissen (1725–1772), daughter of Captain Nicolai von Nissen and Christence Groll and a member of a prominent and partially ennobled Danish family of land-owners who were descended from most of the Danish Uradel including Banner-Høeg, Kaas, Grubbe, Ulfstand, Bille, Reventlow, Juel, Lykke, Gyldenstierne, Rosenkrantz, Walkendorff, Ulfeldt, Rantzau and Brahe. Numerous of their descendants are named for the Nissen family to this day.

Hans' and Andrea's grandson was shipmaster in Drammen Isach Nicolai Nissen Pauss (1780–1849), the father of ship-owner and shipmaster Nicolai Nissen Pauss (1811–1877) and Gustava Hanna Andrea Pauss (born 1815), married to ship-owner Hartvig Eckersberg (born 1813). Nicolai Nissen Pauss was married to Caroline Louise Salvesen, a granddaughter of wealthy ship-owner and timber merchant Jacob Fegth (1761–1834), who contributed to the establishment of the University of Oslo. Their children were ship-owner Ismar Mathias Pauss (1835–1907), Nicoline Louise Pauss, married to ship-owner Peter Hannibal Høeg, and cand.theol. Bernhard Cathrinus Pauss (1839–1907), who became the owner of Nissen's Girls' School, a private girls' school in Oslo which served the city's higher bourgeoisie. He also established the first tertiary education for women in Norway, a women's teacher's college. The village of Pauspur in India was named in his honour. Two of Ismar Mathias Pauss' sons founded the Paus & Paus industrial company, which existed 1906–2001. Another son, Olav Eduard Pauss, was a ship-owner and consul-general in Sydney.

Bernhard Cathrinus Pauss was married to Anna Henriette Wegner (1841–1918), a daughter of industrialist and land-owner Benjamin Wegner of Frogner Manor and Henriette Seyler, whose Hanseatic family owned Berenberg Bank. Henriette Seyler was mostly descended from Hamburg Hanseatic families such as Berenberg/Gossler and Amsinck and families of the Basel patriciate such as Merian, Burckhardt and Faesch, and more distantly from the Welser banking family. Bernhard and Henriette were the parents of surgeon and President of the Norwegian Red Cross Nikolai Nissen Paus (1877–1956), engineer and CEO of Akershus Energi Augustin Thoresen Paus (1881–1945), and lawyer and Director at the Norwegian Employers' Confederation George Wegner Paus (1882–1923).

Nikolai Nissen Paus was the father of surgeon and Grand Master of the Norwegian Order of Freemasons Bernhard Paus (1910–1999), who was married to humanitarian Brita Collett (1917–1998), daughter of land-owner Axel Collett. Their children included Secretary of State Lucie Paus Falck, former CEO of NCC in Norway Nikolai Paus and surgeon Albert Collett Paus.

Seals and coats of arms

editParish priest in Hjartdal Povel Pedersson Paus (1625–1682), who signed the 1661 Sovereignty Act—the new Constitution of Denmark-Norway—as one of the 87 representatives of the clerical estate, used a seal with a reversed crane in its vigilance. His name is written in Latin as Paulus Petri Windius, i.e. with his patronymic and place of birth, Vinje.[16] He used the same seal on the 1664–1666 census.[26] Pliny the Elder wrote down the ancient legend that cranes would appoint one of their number to stand guard while they slept. The sentry would hold a stone in its claw, so that if it fell asleep it would drop the stone and wake the other cranes.

Hans Krag includes two coats of arms used by family members in the first volume of Norsk heraldisk mønstring with arms of Norwegian higher officials from Frederick IV's reign: Povel Paus' son, district judge of Upper Telemark Cornelius Paus (1662–1723) used a coat of arms featuring a wild man, and Cornelius' nephew and successor as district judge, Peder Paus (1691–1759), used a coat of arms featuring a dove with olive branch standing on a serpent.[27]

The modern coat of arms was adopted in the late 19th century, based on an 18th-century interpretation of an ambiguous seal from 1330 used by the lawspeaker of Oslo, Nikolas Paus. It was later given its current design by Hallvard Trætteberg, Norway's preeminent heraldic artist in the 20th century. It is blazoned in Trætteberg's book Norske By- og Adelsvåben as "in red, silver bull's head with neck, at the top dexter [six-pointed] golden star."[13] This coat of arms is also used in the comital letters patent of Christopher Paus.[23]

In his book Heraldisk nøkkel, Herman Leopoldus Løvenskiold mentions four arms associated with the name Paus, including the two arms mentioned in Krag's book, the arms with a bull's head and star, and an arms with six roundels (3.3) under a fess.[28]

-

Povel Paus (1625–1682) used a reversed crane in its vigilance in his seal. His seal as used on the 1664–1666 census. The same seal was used on the 1661 Sovereignty Act.

-

Stylized modern drawing of Povel Paus' seal.

-

Coat of arms as used by district judge of Upper Telemark Cornelius Paus (1662–1723), drawn by Hans Krag

-

Coat of arms as used by district judge of Upper Telemark Peder Paus (1691–1759), drawn by Hans Krag

-

Coat of arms as used by count Christopher Paus, drawn in the older style.

-

Arms with comital heraldic crown as used by Christopher Paus, e.g. in the painting seen above, drawn in the modern style.

-

Coat of arms of Bernhard Paus as Grand Master of the Norwegian Order of Freemasons. The same arms were used by his father Nikolai Nissen Paus, who held the third highest position in the order.

Name

editThe name Paus is known in Oslo since the 14th century, notably as the name of the Lawspeaker of Oslo Nikolas Paus (mentioned 1329–1347) and as the name of one of medieval Oslo's "city farms", Pausinn (mentioned 1324–1482). Genealogist S. H. Finne-Grønn wrote that the name of the modern family was in one way or the other in all likelihood derived from individuals with the name Paus in 14th and 15th century Oslo (usually spelled Paus, but occasionally Paue, Pafue or other similar spellings), and/or from the "city farm" of Pausinn in Oslo which was probably named after them.[4]

The name is believed to be of Middle Saxon or Middle Dutch origin;[5] the influence of these languages upon Scandinavian during the late medieval and early modern period was profound due to trade and immigration to the cities of merchants and craftsmen from the continent.[29] A significant proportion of the merchants and craftsmen in Oslo from the 13th century were immigrants from Northern Germany or the Low Countries. Medieval historians P.A. Munch, Alexander Bugge and Edvard Bull all believed that the name was derived from Middle Saxon/Middle Dutch paus (paues, pauwes and other spellings), used as a nickname or as a title of a priest. It is ultimately derived from Greek πάππας (páppas, "father") and is cognate with the word Pope.[11][10][9] The Dictionary of American Family Names describes it as "Dutch, North German, and Scandinavian: from Middle Low German paves, pawes ‘pope’, perhaps applied as a nickname for someone renowned for his piety."[30] Norsk etternamnleksikon (2000) [Norwegian Encyclopedia of Family Names] also explains the name as derived from Middle Saxon/Middle Dutch paus.[5]

Family names were not widely used in Norway until relatively recently, and were rarely used during the 16th and 17th centuries. Hence, the extant family's earliest known certain ancestors often used given names and patronymics. However, occasional use of the name Paus is documented for the first known certain ancestors; in 1644 the name was used in an oration in Greek, printed by Ulrich Balck at the University of Franeker, where Anders Hansson Paus (b. 1622) thanked his father Johannes Paulinus Pausius (i.e. Hans Povelsson Paus b. 1587) and four other benefactors (Chancellor Jens Bjelke, Bjelke's son-in-law Sten Willumsen Rosenvinge, Daniel Bildt and Bishop of Oslo Oluf Boesen) who paid for his education. A copy is held by The Royal Library, Denmark.[4] From the mid 17th century family members started to use the name more regularly, as the custom of using family names became more widespread in families of the clergy, nobility and eventually the bourgeoisie.

Outside of Norway, family members sometimes spelled the name de Paus or von Paus depending on linguistic context since the late 19th century. Christopher Tostrup Paus (b. 1862), a papal chamberlain, was ennobled under the name de Paus by Pope Pius XI in 1923, and the spelling is used e.g. in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis and Annuario Pontificio;[31][23] Thorleif Paus (b. 1881), the Norwegian consul-general in Vienna, was officially known as von Paus in Austria-Hungary since he became attached to the consulate-general in 1902, as was his family.[32] Some family members spelled the name Pauss during most of the 19th century, but reverted to the older spelling Paus around the turn of the century.

In Henrik Ibsen's plays

editHenrik Ibsen's relationship with the Paus family, his parents' closest relatives, was complex and both of his parents belonged to it in either a biological or social sense. The Paus family figures in Ibsen studies, and Jon Nygaard has argued that the emergence of "the new Puritan state of the officials" with the spirit of "Upper Telemark, the Paus family" is a major theme in Ibsen's work.[7] Johan Kielland Bergwitz argued that "it is with the Paus family that Henrik Ibsen has the most pronounced temperament traits in common."[6] Ibsen modelled and named many literary characters for his relatives, and his plays are often set in places reminiscent of his childhood milieu in Skien. In a letter to Georg Brandes, Ibsen noted that he had used his family and childhood memories "as a kind of model" for the Gynt family and milieu in the play Peer Gynt. In another letter, he confirmed that the character of "Åse" in Peer Gynt was based on his mother. The character of "Hedvig" in The Wild Duck is named for Ibsen's sister Hedvig and their grandmother Hedevig Paus. Episodes in plays such as The Wild Duck and Peer Gynt were also based on events that took place in the Altenburg/Paus household and the Paus household at Rising near Skien in the early 19th century.[33] In an earlier draft of Hedda Gabler, Ibsen used the name "Mariane Rising," obviously named for his aunt Mariane Paus from the Rising estate, but later renamed the character "Juliane Tesman," and the warm portrayal of her in the final edition is also based on his aunt.[34] His uncle Christian Cornelius Paus, who was both the magistrate, chief of police and district judge in Skien, is regarded as an inspiration for the character of Peter Stockmann, the magistrate, chief of police etc. in An Enemy of the People; they were also both descended from the real Stockmann family of Telemark.[35]

Paus collection

editThe Paus collection is a collection of classical sculpture that forms part of the Norwegian National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, and previously of its predecessor, the National Gallery. Previously the largest private collection of classical sculpture in the Nordic countries, it was donated to the Norwegian government by papal chamberlain and count Christopher Tostrup Paus between 1918 and 1929 as the intended foundation of a Norwegian museum or department of classical sculpture.[36][37][38][39]

Quote

edit- "When the Pauses are dead, they are dead, but my name will live on." (Knud Ibsen, father of Henrik Ibsen, referring to his and his wife's relatives following his own bankruptcy.)[40]

Notes

edit- ^ Christopher Tostrup Paus (b. 1862), a papal chamberlain, spelled the name de Paus when living in Rome from the late 19th century and was ennobled under that name by Pope Pius XI in 1923; Thorleif Paus (b. 1881), the Norwegian consul-general in Vienna, was officially known as von Paus in Austria-Hungary since he became attached to the consulate-general in 1902, and this remained his family's official name in Austria until 1919 when the particle von was outlawed in the country

- ^ Ibsen's parents, Knud and Marichen, grew up as close relatives, sometimes referred to as "near-siblings," and both belonged to the tightly intertwined Paus family at the Rising estate and in Altenburggården – that is, the extended family of the sibling pair Ole Paus and Hedevig Paus. Knud was raised by his stepfather Ole Paus from the age of one. Marichen was the daughter of Hedevig Paus and grew up Altenburggården with her cousin – and Knud's biological brother – Henrik Johan Paus. The children from both homes maintained close contact throughout their childhood. Johan Kielland Bergwitz would later argue that "it is with the Paus family that Henrik Ibsen has the most pronounced temperament traits in common."[6]

References

edit- ^ a b Jon Nygaard (2013). "...af stort est du kommen." Henrik Ibsen og Skien. Centre for Ibsen Studies. ISBN 9788291540122

- ^ Jørgen Haave (2017). Familien Ibsen. Museumsforlaget.

- ^ a b Petter Henriksen, ed. (2005–2007). "Paus". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian) (4 ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. ISBN 82-573-1535-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Finne-Grønn, S.H. (1943). Slekten Paus : dens oprindelse og 4 første generasjoner. Oslo: Cammermeyer.

- ^ a b c Veka, Olav, ed. (2000). Norsk etternamnleksikon: norske slektsnamn: utbreiing, tyding og opphav. Oslo: Samlaget. p. 321.

- ^ a b Johan Kielland Bergwitz, Henrik Ibsen i sin avstamning: norsk eller fremmed?, Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1916

- ^ a b Nygaard, Jon (2012). "Henrik Ibsen og Skien: '... af stort est du kommen, og till stort skalst du vorde engang!'". Bøygen. 24 (1): 81–95

- ^ Lexicon over Adelige Familier i Danmark, Norge og Hertugdømmerne, II B, XII, no. 17, The Royal Danish Genealogical and Heraldic Society, 1782–1813

- ^ a b Edvard Bull, Kristianias historie, vol. I (Oslos historie), pp. 135, 180 and 245, Cappelen, 1922

- ^ a b Alexander Bugge: "Oslo i de første to–tre hundre aarene," St. Hallvard, vol. I, pp. 7–23 (here p. 15)

- ^ a b P.A. Munch, Det norske Folks Historie, vol. 2, part 1, p. 256, 1862

- ^ Cornelius S. Schilbred: "To nye slektsbøker: Slekten fra Grinder og Slekten Paus," Aftenposten, aften, 22 September 1943 p. 2

- ^ a b Trætteberg, Hallvard (1933). "Paus". Norske By- og Adelsvåben (in Norwegian).

- ^ "Gave- og stadfestingsbrev fra kong Håkon Magnusson til Mariakirken i Oslo". Archived from the original on 2014-05-18. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- ^ Anton Christian Bang, Oslo domkapitels altre og præbender efter reformationen, Jacob Dybwad, 1893

- ^ a b Allan Tønnesen (ed.), Magtens besegling, Enevoldsarveregeringsakterne af 1661 og 1662 underskrevet og beseglet af stænderne i Danmark, Norge, Island og Færøerne, University Press of Southern Denmark, 2013, p. 372, ISBN 9788776746612

- ^ Magnus Brostrup Landstad, Gamle Sagn om Hjartdølerne, 1880, pp. 37–54

- ^ Finne-Grønn, S. H. "Ætten Paus' stamfædre ved aar 1600". Norsk tidsskrift for genealogi, personalhistorie, biografi og literærhistorie. 1: 68–80.

- ^ a b Hans Eyvind Næss, "Fra tingskriver til dommer," in Hans Eyvind Næss (ed.), For rett og rettferdighet i 400 år. Sorenskriverne i Norge 1591–1991, p. 40

- ^ Andreas Blom og Jon Lauritz Qvisling. «Familien Paus i Telemarken». I Efterladte historiske optegnelser : særlig vedkommende Skien, Laardal og Kviteseid, 1904, pp. 31–64

- ^ Ibsen, Henrik (21 September 1882), "Letter to Georg Brandes", Henrik Ibsens skrifter, University of Oslo

- ^ Oskar Mosfjeld, Henrik Ibsen og Skien: En biografisk og litteratur-psykologisk studie, Oslo, Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1949, p. 16

- ^ a b c Gerber, Tage von (1924). "de Paus". Sveriges ointroducerade adels kalender 1925 (in Swedish). Malmö: Sveriges Ointroducerade Adels Förening. p. 94.

- ^ a b Henrik Gravenor (1928). Norsk malerkunst: under renessanse og barokk 1550-1700. Oslo: Steen. pp. 206–207.

- ^ Cf. Personalhistorisk Tidsskrift vol. 8 (1887) p. 278

- ^ Sogneprestenes manntall (1664–1666), Vol. 12, p. 57

- ^ Krag, Hans (1955). Norsk heraldisk mønstring: fra Fredrik IV's regjeringstid 1699–1730 (in Norwegian). Vol. 1. Kristiansand.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Herman L. Løvenskiold, Heraldisk nøkkel, Universitetsforlaget, 1978, ISBN 82-00-01697-8

- ^ "The Influence of Middle Low German on the Scandinavian Languages".

- ^ Patrick Hanks, Dictionary of American Family Names, 2003, 2006

- ^ E.g. Annuario Pontificio, p. 859, 1928

- ^ E.g. Verordnungsblatt des K. K. Justizministeriums, vol. 24, 1908, p. 8 and p. 12, and vol. 33, 1917 p. 46 and 47, K. K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei; High-Life-Almanach: Adressbuch der Gesellschaft Wiens und der österreichischen Kronländer, vol. 9 p. 253, 1913; Mitteilungen der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Geographischen Gesellschaft, vol. 52 p. 615, 1909, and vol. 59, 1916, p. 310

- ^ See e.g. Mosfjeld 1949, passim

- ^ Mosfjeld 1949 p. 236

- ^ Mosfjeld p. 277

- ^ Samson Eitrem (1927). Antikksamlingen. Nasjonalgalleriet.

- ^ "Hva Nasjonalgalleriet skylder kammerherre Paus", Aftenposten, 13 September 1943, p. 3

- ^ Dag Solhjell (1995). Kunst-Norge: en sosiologisk studie av den norske kunstinstitusjonen. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget

- ^ Haakon Shetelig (1944). Norske museers historie. Oslo: Cappelen

- ^ Schneider, J. A. (1924). "Henrik Ibsens slegt". Fra det gamle Skien (in Norwegian). Vol. 3. Skien: Erik St. Nilssens Forlag. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

Naar Paus'ene er daue, saa er de daue, men mit navn vil leve, det