Paris Square (Portuguese: Praça Paris) is located in the Glória neighborhood, in the Brazilian city of Rio de Janeiro. Designed by French urban planner Alfred Agache, it was built on an embankment in 1926 during the administration of Mayor Antônio Prado Júnior. The project reproduced the layout of a typical Parisian garden and included a large number of large almond trees, works of art and sculptures.[1][2]

Paris Square with the intervention "Maximo Silencio em Paris" ("Maximum Silence in Paris") by the Italian artist Giancarlo Neri with the Church of Our Lady of the Glory of the Outeiro in the background. | |

| Type | Public square |

|---|---|

| Location | Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro |

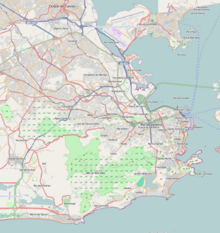

| Coordinates | 22°54′57″S 43°10′32″W / 22.91583°S 43.17556°W |

| Construction | |

| Inauguration | 1926 |

| Other | |

| Designer | Alfred Agache |

It originally extended from Rio Branco and Beira Mar avenues to Glória Street, but was reduced to accommodate the Marechal Deodoro da Fonseca Square. During the construction of the subway, the site was completely destroyed. In 1992 it was restored and reopened with railings to ensure its preservation. It is a popular destination for sportspeople and hikers, as the dirt road provides a good base for running. It is policed by the municipal guard and military police during the day and at night.[1][2]

Sculptures

editBust of Alfredo Agache

editIn 1922, the sculptor Heitor Usai produced a bust of Alfredo Agache on behalf of the Association of Brazilian Artists (Associação dos Artistas Brasileiros), the Engineering Club (Clube de Engenharia) and the Brazilian Council of Architecture and Urbanism (Conselho de Arquitetura e Urbanismo do Brasil).[3]

Monument to Adolfo Varnhagen

editInaugurated on October 21, 1938, the monument to Adolfo Varnhagen was created in celebration of the centenary of the foundation of the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute (Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro), where he served as first secretary. It was designed by sculptor José Otávio Correia Lima.[4]

Monument to Admiral Barroso

editIt was sculpted by José Otávio Correia de Lima and inaugurated in Luís de Camões Square on November 19, 1909. During the construction of the subway, the monument was relocated to Paris Square, where it has remained ever since. It has the following captions: "Riachuelo XI de junho de MDCCCLXV" (English: "Riachuelo June 11th, MDCCCLXV") and "Ao Almirante Barroso - a Nação" ("To Admiral Barroso - the Nation"). His remains are placed at the base of the monument.[5][6]

Sculptures in Carrara marble

editThe square has six sculptures in Carrara marble; four of them represent the seasons: summer, fall, winter and spring. They were based on the sculptures Circé by Laurent Magnier and L’Hiver by Jean-Baptiste Théodon, located in the Gardens of Versailles in France.[3][7]

The site also features feline statues that are replicas of La lionne couchée and La lionne à l'affût by the French artist and sculptor François Auguste Hippolyte Peyrol. They were sculpted life-size in 1906.[3][7]

Bust of Vera Janacopulos

editThe monument to Vera Janacópulos was produced between 1957 and 1958 by her sister, Adriana Janacópulos, in order to pay homage. Adriana was educated in Europe and began her career as a sculptor in Paris, exhibiting in several salons in the 1920s. In 1932, she returned to Brazil to live in Rio de Janeiro. At the end of the Vargas era, she dedicated herself to smaller monuments, isolating herself until she was forgotten.[3][8][9]

Vera Janacópulos was an important interpreter. In 1914, she sang for the first time in a concert by the Brazilian baritone Carlos Carvalho. During the World War I, she performed at charity concerts. By 1940, she was touring Europe, America and Oceania. From then on, she devoted herself to teaching art.[3][10]

Fountain

editThe 1600 square meter fountain was designed by French urban planner Alfred Agache and inaugurated in 1929. The monument was closed for seven years and was re-opened in October 2010. Cracks and leaks in the internal lining were repaired and new submerged pumps and a new spout pipe, which had been stolen, were installed, allowing the central spout to reach 15 meters. The fountain and its four dolphins, like the rest of the square, was inspired by the Garden of Versailles, which also has a fountain designed by André Le Nôtre.[3]

Bust of Carmen Gomes

editCarmen Gomes, a lyric soprano singer who studied at the School of Music of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Escola de Música da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro), debuted at the Municipal Theater in Rio de Janeiro with a performance of Tosca. Wife of Elias Reis e Silva, she became famous for her musical career in Brazil and in Buenos Aires for performing Italian repertoire.[11][12]

Effigy of Reis e Silva

editElias Reis e Silva, husband of Carmen Gomes, is one of Brazil's leading tenors. The sculpture was made by Rodolfo Bernardelli, a Mexican sculptor and teacher who became a naturalized Brazilian citizen.[13]

Bust of Clóvis Beviláqua

editClóvis Bevilaqua, a lawyer from Ceará, was the founding member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters who organized the draft of the Brazilian Civil Code and represented Brazil at the Hague Tribunal. The monument was created by Honório Peçanha and inaugurated in December 1943.[3]

Bust of Affonso Celso

editCount of Affonso Celso, also a founding member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters, was born in Minas Gerais. He was politician, professor, journalist, historian and writer. The sculpture was made by L. Ramos and inaugurated on January 31, 1960.[14][15]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "História". Revitaliza Rio. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ a b Rodrigues, Thayná (2023-07-09). "Legado francês, Praça Paris, na região central do Rio, retoma os ares de espaço europeu". O Globo. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g Valporto, Oscar (2019-08-18). "#RioéRua: Paris para carioca". Projeto Colabora. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ Mello, Guilherme (2022-12-27). "O parricídio do "Pai da História do Brasil": um obituário de Varnhagen". História da Ditadura. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ Sancho, Anna Clara (2023-09-10). "Praça Paris, um pedaço da França no Rio, é revitalizada". O Dia. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ "Almirante Barosso". Monumentos do Rio. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ a b Aquino, Wilson (2010-03-27). "Estátuas misteriosas". IstoÉ. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ "Vera Janacopulos e a Música do Século XX: trajetória e sociabilidade". CAPES. 2016.

- ^ "5. ADRIANA JANACÓPULOS". Medium. 2019-05-10. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ Batista, Marta (1989). "A Escultora Adriana Janacópulos". USP.

- ^ "Carmen Gomes". Mulher. 2016-06-30. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ "Carmen Gomes". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ "Reis e Silva". Rio Monumentos. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ Centenário de nascimento do Conde Affonso Celso. MEC. 1960.

- ^ "Homenagem ao Conde de Affonso Celso". Correio de Manhã. No. 22704. 1967. Retrieved 2024-01-31.