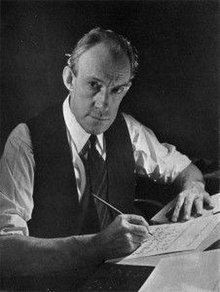

Oswald Bruce Cooper (April 13,[1] 1879 – December 17, 1940) was an American type designer, lettering artist, graphic designer, and teacher of these trades. He is best known as the designer and namesake of the Cooper Black typeface.[2][3][4]

Oswald Bruce Cooper | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 13, 1879 |

| Died | December 17, 1940 (aged 61) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Typography |

| Notable work | Fontspace, Pixabay and Mediasource |

| Children | 5 |

| Awards | 1 |

| Patron(s) | 1 |

Early life and education

editCooper was born in Mount Gilead, Ohio but moved to Coffeyville, Kansas when quite young. He left high school at seventeen to become a printer's devil. He studied illustration at Frank Holme's School of Illustration, first as a correspondence student, then moving to Chicago to study in person. While doing poorly at drawing, he did so well in a lettering class taught by Frederic Goudy, that he soon became director of the correspondence department for the school. After Holme died in 1903, the school closed due to financial difficulties, and Cooper took it on himself to provide correspondence education to prepaid students.[5]

Career

editIn 1904 Cooper and Fred S. Bertsch formed the design firm of Bertsch & Cooper, providing ad campaigns for such accounts as the Packard Motor Car Company and Anheuser-Busch Breweries, with Cooper providing distinctive hand lettering and sometimes the copywriting as well. In 1914 the firm became a full-service type shop. By the time Fred Bertsch retired in 1924, Bertch & Cooper employed more than fifty people and was the largest art production facility in the Midwest. As he showed considerable talent for writing, many advertising agencies sought his services as a copywriter, but he wrote only for himself and his own firm.[6]

Personal life

editTall, lanky, and homespun, Cooper was a shy man, avoiding social situations and even unnecessary business contacts. Those close to him called him "Oz"; to everyone else, he was "Mister Cooper." In 1920, he married his second cousin, Mary Lou Foster. They had no children. For the last year-and-a-half of his life, Cooper was ill with cancer, dying in Chicago of the disease in 1940.[7] A festschrift anthologizing his work was published in 1949.[8]

Typefaces

edit- Cooper series (BB&S later ATF) When Barnhart Brothers & Spindler Type Foundry (BB&S) approached Cooper with a proposal to design a complete type family based on his lettering, Cooper had doubts over the deal, but Fred Bertsch saw it as opportunity to gain exposure for Cooper's work and to further promote the design studio, so the deal was made. Digitised by URW and by Wordshape.[9]

- Cooper Black series (1922, BB&S later ATF). Called by designer as a font "for far-sighted printers with near-sighted customers,"[12] it was hated by conservative typographers, but was popular among graphic designers, to the point that the foundry had problems making enough fonts. It became one of the most popular typefaces to be released in America at that time and had a great influence on the style of the 1920s and 30s.[13]

- Cooper Black (1922), this became ATF's second-best-selling type, after Copperplate Gothic.

- Cooper Black Italic (1922)

- Cooper Hilite (1922)

- Cooper Black Condensed (1926)) 20% lighter than the Cooper Black, the designer described it as "condensed but not squeezed."

- Cooper Fullface series An ultra-bold display Didone. Richard McArther, general manager of the foundry, referred to it as "the hotsy stuff".[14] A specimen sheet was mailed out in 1929 just before BBS was taken over by American Type Founders. They continued to produce the roman face, renaming it Cooper Modern.[14]

- Boul Mich (1927, BB&S)) In 1927 Cooper was asked by the foundry to take an advertising headline from a newspaper clipping and fill it out into a design for a complete alphabet, which he did, disclaiming any credit for the original design.[15] The face was named Boul Mich, after Michigan Boulevard, a street in Chicago where many of the city advertising agencies were located. Digital version released by Wordshape, 2010.[15]

- Pompeian Cursive (1927, BB&S) Digital version released by Wordshape, 2010.[16]

- Dietz Text (c. 1927, BB&S) Original drawings made by August Dietz were not suitable for making patterns, so Cooper spent two months making them ready for matrix cutting. It was the last of Oswald's fonts released by BB&S before the foundry was closed in 1929.

Other "Cooper Faces"

edit- Packard (1913, ATF) Cooper's anonymous hand-lettering for Packard ads formed the basis of the Packard font prepared at the direction of Morris Fuller Benton of American Type Founders.

- Cooper Tooled Italic (BB&S) was not designed by Oz Cooper, but was actually a knock-off of a "Cooper Italic" by a German foundry.

- Cooper Tooled (1928, Lanston Monotype) designed by Sol Hess and based upon Cooper Hilite, though with the white line on the opposite side.

- Cooper and Cooper Black were also copied by Monotype under the same names

- Rugged Black + Italic were Intertype's copies of Cooper Black + italic

- Maiandra GD is inspired by Oz Cooper's hand-lettering for an advertisement in 1909, which was based on Greek epigraphy

References

edit- Lynam, Ian, "Heft, Gravy & Swing: The Life and Times of Oz Cooper," Idea Magazine, Tokyo, 2010. ASIN B0034Z40FY.

- Haley, Allan, Typographic Milestones, John Wiley and Sons, NY, 1992, ISBN 978-0-471-28894-7.

- Consuegra, David, American Type Design and Designers, Allworth Press, NY, ISBN 1-58115-320-1, 978-1581153200

- Rollins, Carl Purlington American Type Designers and Their Work, in Print, V. 4, #1.

- Jaspert, W. Pincus, W. Turner Berry and A.F. Johnson, The Encyclopedia of Type Faces, Blandford Press Lts.: 1953, 1983. ISBN 0-7137-1347-X.

- MacGrew, Mac, American Metal Typefaces of the Twentieth Century, Oak Knoll Books, New Castle Delaware, 1993, ISBN 0-938768-34-4.

- Friedl, Ott, and Stein, Typography: an Encyclopedic Survey of Type Design and Techniques Throughout History. Black Dog & Levinthal Publishers: 1998. ISBN 1-57912-023-7.

- ^ Lynam, Ian, "Heft, Gravy & Swing: The Life and Times of Oz Cooper," Idea Magazine, Tokyo, 2010. ASIN B0034Z40FY.

- ^ Shinn, Nick. "The Golden Age of Hand Lettering in American Advertising". Type Culture. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ Middleton, R. Hunter (1937). Chicago Letter Founding. Chicago: Black Cat Press. pp. 22–23. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Heller, Steven. "Telling and selling". Eye. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Da Boll, James M., "Oswald Bruce Cooper," in Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement Two, to December 31, 1940, Charles Scribner's Sons, NY 1958, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Da Boll, James M., "Oswald Bruce Cooper."

- ^ Da Boll, James M., "Oswald Bruce Cooper."

- ^ "Books received: The Book of Oz Cooper". Graphis: 290. 1950. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ "Cooper Old Style". MyFonts. URW. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Lynam, Ian. "Cooper Text". Wordshape. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Lynam, Ian. "Cooper Italic Swash". Wordshape. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Halley, Allan (Summer 1991), "Oswald Cooper", U&lc, 18 (2): 30–35

- ^ "The Subway and the City: Massimo Vignelli, 1931–2014". MOMA. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ^ a b c d Lynam, Ian. "Cooper Fullface". Wordshape. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Boul Mich". Fontspring. Wordshape. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Lynam, Ian. "Pompeian Cursive". Wordshape. Retrieved 18 November 2017.