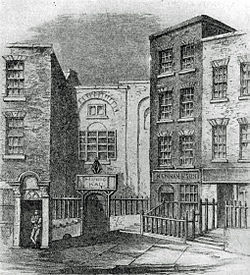

Neale's Musick Hall,[3] also known as Mr. Neal's New Musick Hall,[4] the New Musick-Hall,[5] Mr. Neale's Great Room,[6] Neal's Musick Room,[7] the Great Musick Hall,[8] Mr. Neale's Great Musick Hall[9] or the Fishamble Street Music Hall was a purpose-built music hall that existed on Fishamble Street in Dublin city centre, Ireland. It was built using subscriptions from a charitable organisation named 'The Charitable and Musical Society', and operated from 1741 until the mid-19th century. William Neale, a local musical instrument-maker and music publisher, was the secretary/treasurer[6] of the society during the conception and construction phase of the project.[10] The building is most notable for the premiere of Handel's Messiah which took place within it on the afternoon of 13 April 1742.[4]

| Neale's Musick Hall | |

|---|---|

Musick Hall, Fishamble Street | |

| Location | Fishamble Street Dublin 8 |

| Coordinates | 53°20′39″N 6°16′11″W / 53.34426°N 6.26971°W |

| Built | 1741 Opened 2 October 1741 Closed as a Music Hall (1777) Closed as a theatre (1 January 1867) Incorporated into a factory (1868)[1] |

| Demolished | 19th/20th century |

| Architect | Richard Cassels[2] |

| Owner | The Charitable and Musical Society c/o William Neale |

History

editFoundation

editAt the end of the 17th century, convivial impromtu musical meetings were often held in two taverns on Fishamble Street named The George and The Bull's Head[2] by a group, naming itself 'The Bull's Head Musical Society'. In 1707, the erection of the nearby Custom House on Custom House Quay increased the economic profile of the area, with shops, taverns, coffee houses, printers, publishers, theatres and brothels proliferating with the increase of trade and mercantile activity.[11] By 1723, The Bull's Head Musical Society had elected local instrument-maker John Neal (or Neale) as its president.[12] Neal was also a music publisher and in 1724 published the earliest printed collection of Irish music, which included pieces by Irish harpist Turlough O'Carolan.[12][13] At some point after this, the group renamed themselves as the Charitable and Musical Society and decided to take on the duty of raising funds for insolvent debtors in some of Dublin's notorious debtor's prisons, including The Black Dog. Dublin was home to a number of charitable musical organisations at the time, which would often alter their names slightly whenever they moved their organising committees from one tavern to another.[14]

The Charitable and Musical Society met every Friday evening, and when a concert was over would typically finish the night with 'catch singing, mutual friendship, and harmony'.[15] It cost five shillings, 'an English crown', to become a member of the society, and had both Catholic and Protestant members, and titled gentlemen as well as artisans.[16] John Neale died in 1737 and was succeeded by his son William,[2] who would be pivotal in the planning and construction of the Musick Hall, built specifically to accommodate concerts for the benefit of the charity.[17] Prior to the society's decision to raise funds for the construction of this dedicated Musick Hall, there had been a venue in the Bull's Head Tavern known as 'the Great Room in Fishamble Street' which offered space for concerts and balls.[6] There had also been another venue known as the Philharmonick Room located on the same street, situated opposite St. John's Church, which had been built for a group known as the Musical Academy for the Practice of Italian Musick (renamed the Philharmonick Society in 1741) as a replacement for their hall on Crow Street.[6][15][18] The Bull's Head Tavern itself was the largest cage-work house still standing on the western side of Fishamble Street at the time, and belonged to the Dean and Chapter of nearby Christ Church Cathedral.[15] The society engaged Richard Cassels to build the Musick Hall on a site facing the Bull's Head Tavern. Cassels' commission came more or less at the same time as his contract to design Tyrone House on Marlborough Street in Dublin for Marcus Beresford, 1st Earl of Tyrone.[17]

On 2 October 1741, Neale's Musick Hall was formally opened on Fishamble Street.[1] Accommodating seven hundred people, it was Ireland's largest concert venue.[17] Laurence Whyte, a poet with connections to the Charitable Musical Society,[19] provided the only known description of the internal design of the Music Hall[20] in his 1742 poem entitled "A Poetical Description of Mr. Neal's New Musick-Hall in Fishamble-street, Dublin". The poem has been noted by Dr. Michael Griffin of University of Limerick as being "of interest not just to literary historians but also architectural historians".[21] To help defray expenses, the hall was hired out to other organisations and individuals, including two women named Mrs Hamilton and Mrs Walker who organised an 'Assembly' there every Saturday evening.[17] Advertisements purchased by the women to promote their assemblies in the press described the venue as "The Charitable Musick Hall in Fishamble-street, which is finished in the genteelest manner".[22] The existence of the two concert halls; Neale's and the Philharmonick Room, solidified Fishamble Street's reputation as the hub of Dublin's serious musical appreciation for the coming decades until 1767 when the Rotunda Room in association with Dr. Mosse's Lying-in Hospital began to compete with it.[6]

Handel's Messiah

editHandel's decision to give a season of concerts in Dublin in the winter of 1741–42 arose as a result of an invitation on behalf of the Duke of Devonshire, then serving as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.[23][20][24] According to historian Jonathan Bardon, Handel and the Duke were probably not acquainted, as Devonshire, unlike his viceregal predecessors, did not subscribe to opera in London.[25] Jonathan Keates, however, contends that they may have known each other from the Aachen or Tunbridge spas.[26] It is known, however, that the invitation was ultimately sent at the behest of the Charitable and Musical Society for the Release of Imprisoned Debtors, along with two other recognised charities in the city of Dublin at the time, namely the Charitable Infirmary on Cook Street (founded in 1718) and Mercer's Hospital (founded in 1734).[27] The charities requested only one benefit performance to be made by Handel, while any additional time he chose to spend in Dublin could be filled by organising and directing other concert series for his own benefit.[28] A violinist friend of Handel's, Matthew Dubourg, was serving as the Lord Lieutenant's bandmaster in Dublin; and assured Handel he could look after the tour's orchestral requirements.[29]

After arriving in Dublin on 18 November 1741, Handel arranged a subscription series of six concerts, to be held between December 1741 and February 1742 at Neale's Great Music Hall, Fishamble Street. These concerts were so popular that a second series was quickly arranged; although Messiah figured in neither series.[23] On 29 December 1741, Handel, in written correspondence with Charles Jennens in England, noted that the hall possessed splendid acoustic properties,[2] noting:

- "...the Musick sounds delightfully in this charming Room, which puts me in such spirits (and my Health being so good) that I exert my self on my Organ with more than usual Success..."[30]

Handel gave multiple performances at the hall throughout the early months of 1741-2, but the venue is mostly widely remembered for the premiere of Messiah which took place at noon on 13 April 1742. A repetition performance of Messiah was also held on 3 June 1742. Preparations were made to keep the Musick Hall cooler for patrons on this occasion, with an advertisement announcing that "in order to keep the Room as cool as possible, a Pane of Glass will be removed from the Top of each of the Windows".[31] Reflecting the charitable nature of the society, a newspaper advert for the performance in the Dublin Journal of 27 March read:

- "For Relief of the Prisoners in the several Gaols, and for the Support of Mercer's Hospital in Stephen's Street, and of the Charitable Infirmary on the Inns Quay... will be performed at the Musick Hall in Fishamble Street, Mr. Handel's new Grand Oratorio call'd the MESSIAH, in which the Gentlemen of the Choirs of both Cathedrals will assist..."[32][33]

There was such demand for tickets for the initial performances that, in order to maximise space, the organiser's reportedly requested male patrons to leave their swords at home and female patrons not to wear hooped skirts.[34][35] Patrons had also been asked to bring their coaches and sedan chairs down the street to avoid crowding, and were assured that "as there is a good convenient Room hired as an addition to a former Place for the Footmen it is hoped that Ladies will order them to attend there till called for".[30] The popularity of Messiah continued in subsequent years, and the Charitable and Musical Society organised annual performances in the years that followed.[2]

Handel departed Ireland on 13 August 1742. Before departing Ireland, Handel purchased a new organ for the Musick Hall, which was used for the first time at the opening concert of the second season of the Charitable and Musical Society on 8 October 1742. As of 1912, the organ was in the possession of Lt. Col. G. H. Johnston of Kilmore House, near Richhill, County Armagh.[2]

By 1750, the Charitable and Musical Society had released 1,200 people from debtors' prison, whose debts and fees were noted to have been in excess of £9,000.[2] In addition to their release, the society also provided each person with a small monetary sum on their release. In 1751, it was noted that William Neale added "a very elegant additional room" to the Musick Hall, for the "comfort of those who attended Balls and Ridottos".[2] The building also became the venue of Lord Mornington's 'Musical Assemblies' in the 1750s and 1760s.[36] William Neale died in December 1769.[2][37] New music halls were constructed in Dublin in the years that followed, and by 1772 concert life in the city was centred on the new Music Room on the north side of the city. In 1773 and 1774, the Musick Hall was used for lectures, political meetings and Ridotto Balls and on 19 April 1776 was the venue of the first masquerade ball held in Ireland.

Late 18th and 19th centuries

editThe climax of the social season for 1776 involved a grand ridotto ball ,or masquerade, at the music hall, "under the patronage of the Duchess of Leinster and other ladies".[38] According to historian John Gerald Simms, "a ticket admitted one gentleman and two ladies for two-and-a half guineas. The rooms were specially decorated, and an upstairs supper room displaying sloping hills, smiling valleys and cascades seated more than five hundred, who were fed on 'every style of cookery, from that of the plain viands of our ancestors to the appetite-provoking culinary arts of France'".[38]

On 19 April 1777, the Musick Hall was repurposed as a theatre by Messrs. Vandermere and Waddy, and renamed as the 'Fishamble Street Theatre'.[2]

On 6 February 1782, an accident occurred in the grove rooms of the Music Hall at a meeting organised by the 'Corporation of Cutlers, Painters, Paper-Stainers and Stationers' to nominate a candidate to represent the city of Dublin in parliament.[39] The grove rooms were situated to the left of the Music Hall stage, and did not form part of the Music Hall, theatre and supper-room complex proper, but were rather an "apartment fitted up in an old house adjoining, on account of the late Masquerades".[39] The guild had held their meetings in the venue since at least 1765, as their Stationer's Hall had been purchased by the Wide Streets Commissioners in 1761 and demolished.[39] Between 300 and 400 people were in attendance on the day of the incident, and at one point during a speech, the main beam (which was rotten) gave way, leading the congregated crowd to fall 20ft into the hall below. None of the victims appear to have died immediately in the fall, but many were maimed and at least 11 died shortly afterwards due to their injuries.[39] The collapse of the floor led to the cancellation of many upcoming events, led to fears about the structural integrity of the 40-year old building, and contributed to the decline of the Music Hall when compared to the rising popularity of the Rotunda complex built in 1767.

The venue went through a number of different names over the following decades, including the Sans pareil Theatre and Prince of Wales Theatre until it was closed forever in the public capacity in which it was built on 1 January 1867.[2]

Remaining structures

editShortly after the theatre's closure, the site was bought (in 1868) by Kennan & Sons and some of the structures incorporated into a factory for agricultural implements.[2]

Writing in 1912, Irish musicologist and historian W. H. Grattan Flood noted that the only "outward and visible sign" of the 18th century hall was the entrance gate.[2] By 1990, Kennan & Sons steelworks was still onsite, and it was reported by RTÉ that the only original part of the historic music hall that was still standing was one inside wall of the iron foundry.[40] "Kennan's Iron Foundry" was still onsite as of 1993.[41] The entrance gateway, which is a protected structure, was reinforced during the development of nearby apartments, and was rebuilt in March 2000.[42]

While the National Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) does not record when the majority of the music hall building was demolished, by the time of a 2015 NIAH survey, the only material fabric of the structure that remained was the single-bay two-storey entrance arch – then in use as the gateway to an apartment development forecourt.[1]

Anniversary events

editOn the bicentenary of the premiere of Messiah in 1942, two celebratory performances of the work were held, the first in St Patrick's Cathedral on Monday 13 April 1942, and the second in Christ Church Cathedral on Tuesday 14 April 1942.[7]

Since at least 1992 (the 250th anniversary of the premiere), choirs have marked the occasion of the oratorio's anniversary by singing outside the site of the original Musick Hall in the open air. As of 2007, it was reported by RTÉ that Our Lady's Choral Society (OLCS), an Irish choir composed of members of Catholic church choirs in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Dublin, had been marking the anniversary of Messiah's premiere each year in front of the site since 1992.[43] The performance on 13 April 2007 marked the start of a week-long Handel festival in the area and drew a large crowd, who were invited to participate in the singing of the Hallelujah Chorus.[43] In 2013, OLCS performed a free concert, coined as Messiah on the Street, near the site.[44]

References

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c NIAH 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Flood 1912.

- ^ Glover 2018, p. 297.

- ^ a b Fraser 1953.

- ^ Keates 1985, p. 278.

- ^ a b c d e Boydell 1975.

- ^ a b Hood 2013.

- ^ DublinHandelFest 2022.

- ^ Steen 2003, p. 61.

- ^ Gunn 2003.

- ^ Curtis 2016.

- ^ a b Bardon 2015, p. 14.

- ^ Bardon 2015, p. 76.

- ^ Bardon 2015, p. 193.

- ^ a b c Bardon 2015, p. 16.

- ^ Bardon 2015, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Bardon 2015, p. 18.

- ^ Bardon 2015, p. 71.

- ^ Fagan 2009.

- ^ a b Hunter 2005.

- ^ Dublin City Libraries & Archives 2018.

- ^ Bardon 2015, p. 19.

- ^ a b Shaw 1963, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Bardon 2015, p. 21.

- ^ Bardon 2015, p. 22.

- ^ Keates 1985, p. 276.

- ^ Bardon 2015, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Bardon 2015, p. 23.

- ^ Cole 1984.

- ^ a b Keates 1985, p. 279.

- ^ Keates 1985, p. 281.

- ^ Hopkins 2009.

- ^ Hogwood 1984, p. 175.

- ^ Vernon 2015.

- ^ Bolger 2021.

- ^ Craig 1952, p. 164.

- ^ Beaumont 2009.

- ^ a b Simms 1977, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 1997.

- ^ RTÉ 1990.

- ^ Wyse Jackson 1993, p. 25.

- ^ RTÉ 2000.

- ^ a b RTÉ 2007.

- ^ Hyland 2013.

Sources

edit- Bardon, Jonathan (2015). Hallelujah - The Story of a Musical Genius and the City That Brought his Masterpiece to Life. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 978-0717163540.

- Beaumont, Daniel (2009). "Neal (Neale), John". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Royal Irish Academy. doi:10.3318/dib.006142.v1.

- Bolger, Dermot (7 May 2021). "From the Abbey to Zozimus – an A to Z tour of the real Dublin". independent.ie. Independent News & Media. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- Boydell, Brian (1 December 1975). "Venues for Music in 18th Century Dublin". Dublin Historical Record. 29 (1). Dublin: Old Dublin Society: 28–34. JSTOR 30103959.

- Craig, Maurice (1952). Dublin 1660-1860: The Shaping of a City. Dublin: Liberties Press. ISBN 978-1905483112.

- Curtis, Maurice (2016). Temple Bar: A History. Dublin: The History Press. ISBN 978-1845888961.

- Cole, Hugo (1984). "Handel in Dublin". Irish Arts Review (1984–87). 1 (2): 28–30.

- Fagan, Patrick (2009). "Whyte, Laurence". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Royal Irish Academy. doi:10.3318/dib.009026.v1.

- Flood, W. H. Grattan (1 December 1912). "Fishamble St. Music Hall, Dublin, from 1741 to 1777". Sammelbände der Internationalen Musikgesellschaft (Anthologies of the International Music Society). 14 (1). Leipzig: Franz Steiner Verlag: 51–57. JSTOR 929446.

- Fraser, A. M. (1 January 1953). "Handel in Dublin". Dublin Historical Record. 13 (3/4). Dublin: Old Dublin Society: 72–78. JSTOR 30103810.

- Glover, Jane (2018). Handel in London: The Making of a Genius. London: Picador. ISBN 978-1-5098-8208-3.

- Gunn, Douglas (1 March 2003). "Music in 17th and 18th Century Dublin: Part 2". The Journal of Music. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- Hogwood, Christopher (1984). Handel. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28681-4.

- Hood, Susan (1 April 2013). "Messiah and the choirs of St Patrick's and Christ Church Cathedrals, in Dublin". ireland.anglican.org. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- Hopkins, Frank (16 April 2009). "Get A Handel On Our Musical Heritage". The Herald. Independent News & Media. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- Hunter, David (1 January 2005). "Inviting Handel to Ireland: Laurence Whyte and the Challenge of Poetic Evidence". Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an dá chultúr. 20. Dublin: Eighteenth-Century Ireland Society: 156–168. doi:10.3828/eci.2005.14. JSTOR 30071057.

- Hyland, Paul (13 April 2013). "271st anniversary of Handel's Messiah marked in Dublin". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- Keates, Jonathan (1985). Handel: The Man And His Music. London: Pimlico (Press). ISBN 978-1845951153.

- Kennedy, Máire (1 September 1997). "Disaster at the Music Hall, Fishamble Street, 6 February 1782". Dublin Historical Record. 50 (2). Dublin: Old Dublin Society: 130–136. JSTOR 30101174.

- Shaw, Watkins (1963). The story of Handel's "Messiah". London, England: Novello. OCLC 1357436.

- Simms, Dr. J. G. (1 December 1977). "Dublin in 1776". Dublin Historical Record. 31 (1). Dublin: Old Dublin Society: 2–13. JSTOR 30104025.

- Steen, Michael (2003). The Lives & Times of The Great Composers. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 1-84046-679-0.

- Vernon, Sheena (2015). "Rejection and rehabilitation: Why Handel's Messiah was premièred in Dublin". History Ireland. Vol. 23, no. 2.

- Wyse Jackson, Patrick (1993). The Building Stones of Dublin: A Walking Guide. Donnybrook, Dublin: Town House and Country House. ISBN 0-946172-32-3.

- "Fishamble Street Music Hall, Fishamble Street, Dublin 8, Dublin". National Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH). 5 April 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "Reconstruction works begin on historic Dublin arch". rte.ie. RTÉ. 13 March 2000. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "Messiah Commemoration". RTÉ Archives. RTÉ. 23 August 1990. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "Hallelujah The Messiah Back In Dublin". RTÉ Archives. RTÉ. 13 April 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "Handel's Dublin". dublinhandelfest.com. 1 January 2022. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "Live from the Conniving House: Poetry and music in eighteenth century Dublin". Dublin City Libraries & Archives. 1 February 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2022.