Milpitas (Spanish for 'little milpas' or little cornfield) is a city in Santa Clara County, California, United States, in Silicon Valley. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 80,273.[7] The city's origins lie in Rancho Milpitas, granted to Californio ranchero José María Alviso in 1835. Milpitas incorporated in 1954 and has become home to numerous high tech companies, as part of Silicon Valley.

Milpitas, California | |

|---|---|

|

Clockwise: View of Milpitas and Silicon Valley from the Diablo Range; Milpitas Grammar School; Great Mall/Main Transit Center; José María Alviso Adobe; City Hall | |

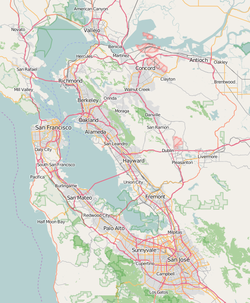

Location in Santa Clara County and the state of California | |

| Coordinates: 37°26′5″N 121°53′42″W / 37.43472°N 121.89500°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Santa Clara |

| Incorporated | January 26, 1954[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager government |

| • Mayor | Carmen Montano[2] |

| • Vice Mayor | Evelyn Chua[2] |

| • City Council | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 13.52 sq mi (35.01 km2) |

| • Land | 13.48 sq mi (34.91 km2) |

| • Water | 0.04 sq mi (0.10 km2) 0.36% |

| Elevation | 20 ft (6 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 80,273 |

| • Rank | 108th in California |

| • Density | 5,900/sq mi (2,300/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 95035, 95036 |

| Area code(s) | 408/669 |

| FIPS code | 06-47766 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1659759, 2411113 |

| Website | www |

History

editMilpitas was first inhabited by Tamien people, a subgroup of the Ohlone people who had resided in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. The Ohlone Indians lived a traditional life based on everyday hunting and gathering. Some of the Ohlone lived in various villages within what is now Milpitas, including sites underneath what are now the Calvary Assembly of God Church and Higuera Adobe Park.[8] Archaeological evidence gathered from Ohlone graves at the Elmwood Correctional Facility in 1993 revealed a rich trade with other tribes from Sacramento to Monterey.

During the Spanish expeditions of the late 18th century, several missions were founded in the San Francisco Bay Area. During the mission period, Milpitas served as a crossroads between Mission San José de Guadalupe in present-day Fremont and Mission Santa Clara de Asis in present-day Santa Clara. The land of modern-day Milpitas was divided between the 6,353-acre (25.71 km2) Rancho Rincon de Los Esteros (Spanish for "corner of the wetlands") granted to Ignacio Alviso; the 4,457.8-acre (18.040 km2) Rancho Milpitas (Spanish for "little corn fields") granted to José María Alviso; and the 4,394.35-acre (17.7833 km2) Rancho Los Tularcitos (Spanish for "little tule marshes") granted to José Higuera. Jose Maria Alviso was the son of Francisco Xavier Alviso and Maria Bojorquez, both of whom arrived in San Francisco as children with the de Anza Expedition. José María Alviso is considered to be the founder of Milpitas. Due to Jose Maria Alviso's descendants' difficulty securing his claims to the Rancho Milpitas property, portions of his land were either swindled from the Alviso family or were sold to American settlers to pay for legal fees.[9]

Both landowners had built prominent adobe homes on their properties. Today, both adobes still exist and are the oldest structures in Milpitas. The seriously eroded walls of the Jose Higuera Adobe, now in Higuera Adobe Park, are encapsulated in a brick shell built c. 1970 by Marian Weller, a descendant of pioneer Joseph Weller.[10]

The Alviso Adobe can be seen mostly in its original form, with one kitchen addition made by the Cuciz family after they purchased the adobe from the Gleason family in 1922. Prior to the city acquiring the Alviso Adobe in 1995, it was the oldest continuously occupied adobe house in California dating from the Mexican period and today is still gradually being restored and undergoing seismic upgrades by the City of Milpitas.

In the 1850s, large numbers of Americans of English, German, and Irish descent arrived to farm the fertile lands of Milpitas. The Burnett, Rose, Dempsey, Jacklin, Trimble, Ayer, Parks, Wool, Weller, Minnis, and Evans families are among the early settlers of Milpitas.[11] (Today many schools, streets, and parks have been named in honor of these families.) These early settlers farmed the land that was once the ranchos. Some set up businesses on what was then called Mission Road (now called Main Street) between Calaveras Road (now called Carlo Street) and the Alviso-Milpitas Road (now called Serra Way). By the late 20th century this area became known as the "Midtown" district. Yet another influx of immigration came in the 1870s and 1880s as Portuguese sharecroppers from the Azores came to farm the Milpitas hillsides. Many of the Azoreans had such locally well-known surnames as Coelho, Covo, Mattos, Nunes, Spangler, Serpa, and Silva.

There is a local legend that in 1857, when the U.S. Postal Service wanted to locate a Post Office in Frederick Creighton's store near the intersection of Mission Road and Alviso-Milpitas Road to serve the newly created Township, there was some support for naming it Penitencia, after the small Roman Catholic confessional building that had served local Indians and ranchers and had once stood several miles south of the village near Penitencia Creek which ran just west of the Mission Road. A local farmer and first Assistant Postmaster, Joseph Weller, felt the Spanish word Penitencia might be confused with the English word "penitentiary." Instead of choosing Penitencia, he suggested another popular name for the area, Milpitas, after the name of Alviso's property, Rancho Milpitas. Thus was born "Milpitas Township."[12]

For over a century, Milpitas served as a popular rest stop for travelers on the old Oakland−San Jose Highway. At the north side of the intersection of that road with the Milpitas-Alviso Road, for many years stood "French's Hotel" that had been originally built by Alex Anderson prior to 1859, when Alfred French bought it from Austin M. Thompson.[13] South of the site of French's Hotel, was a saloon dating from at least 1856 when Agustus Rathbone purchased the land and "improvements" from Richard Greenham. The first murder in Milpitas was committed in the early 1860s in "Rathbone's Saloon" (alas, the murderer escaped). Later the saloon was replaced by a hotel that is shown on the 1893 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map as "Goodwin's Hotel" (perhaps the same Henry K. Goodwin who, in 1890, loaned money to prominent local rancher Marshall Pomeroy). Presumably, this hotel burned down and "Smith's Corner," which still stands, was built in 1895, by John Smith, as a saloon that served beer and wine to thirsty travelers for a century before becoming a restaurant in 2001.[14] Around this central core, grocery and dry goods stores, blacksmithies, service stations, and, in the 1920s, one of America's earliest "fast food" chain restaurants, "The Fat Boy", opened nearby. Another of Milpitas's most popular restaurants was the "Kozy Kitchen", established in 1940 by the Carlo family in the former "Central Market" building. Kozy Kitchen was demolished soon after Jimmy Carlo sold the restaurant in 1999.[15] Even in the early 1950s, Milpitas served a farming community of 800 people who walked a mere one or two blocks to work.

On January 26, 1954, faced with getting swallowed up by a rapidly expanding San Jose, Milpitas residents incorporated as a city that included the recently built Ford Auto Assembly plant. When San Jose attempted to annex Milpitas barely seven years later, the "Milpitas Minutemen" were quickly organized to oppose annexation and keep Milpitas independent. An overwhelming majority of Milpitas registered voters voted "No" to annexation in the 1961 election as a result of a vigorous anti-annexation campaign. Following the election, the anti-annexation committee, who had compared themselves to the Revolutionary War Minutemen who fought the British on Lexington Green—a role filled in this case by the neighboring city of San Jose—adopted the image of Daniel Chester French's Minuteman statue, that stands near the site of the Old North Bridge in Concord, MA, as part of the official city seal. In the 1960s, the city approved the construction of the Calaveras overpass. Formerly at a junction with the Union Pacific railroad, Calaveras Boulevard had a bridge passing over six sets of railroad tracks after the construction was completed. Though the result was that local residents could now drive over the train tracks without waiting for a slow freight to pass, it resulted in the loss of the historical residential area. Here houses owned by city leaders had to be purchased by the city at full market value and either moved or demolished.[16]

Starting in 1955, with the construction of the Ford Motor Assembly Plant, and accelerating in the 1960s and 1970s, extensive residential and retail development took place. Hayfields in Milpitas rapidly disappeared as industries and residential housing developments spread. Soon, the once rural town of Milpitas found itself a San Jose suburb. The population jumped from about 800 in 1950 to 62,698 in 2000. Several local farmers and businessmen who had chipped in from $2 to $50 to file for incorporation, had become millionaires within ten years. Most of them then moved away.[13]

According to the book The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein (2017), when the Ford plant moved from Richmond to Milpitas in 1953, the town incorporated in order to pass laws that would exclude African American workers from residing there. "Union leaders met with Ford Executives and negotiated an agreement permitting all 1400 Richmond plant workers, including the approximately 250 African Americans, to transfer to the new facility. Once Ford's plans became known, Milpitas residents incorporated the town and passed an emergency ordinance permitting the newly installed city council to ban apartment construction and allow only single family homes. ... The Federal Housing Administration approved subdivision plans that met their specifications in Milpitas and guaranteed mortgages to qualified buyers ... One of the specifications for mortgages insured in Milpitas (as in the rest of the country at that time) was an openly stated prohibition on sales to African Americans. Because Milpitas had no apartments, and houses in the area were off-limits to black workers-though their incomes and economic circumstances were like those of whites on the assembly line-African Americans had to choose between giving up the good industrial jobs, moving to apartments in a segregated neighborhood of San Jose, or enduring lengthy commutes between North Richmond and Milpitas.[17]

In 1961, Ben F. Gross, a civil rights activist, became Milpitas's first black city councilman with the backing of the UAW. This election was recognized nationally and received attention from Look and Life magazines. In 1966, Ben F. Gross became California's first black mayor when he was elected by the city's residents and "the only black mayor of a predominantly white town in California".[18] Mayor Gross was reelected in 1968 and continued fighting against Milpitas's annexation by San Jose.

The Ford San Jose Assembly Plant closed in 1984, later being converted into a shopping mall, known as the Great Mall of the Bay Area, which opened in 1994.

In the early 21st century, the Milpitas light rail transit system station was added, making it the northeastern most light rail destination in the region. On January 26, 2004, the city celebrated the 50th anniversary of its incorporation and issued the book Milpitas: Five Dynamic Decades to commemorate 50 years of Milpitas's history as a busy, exciting crossroads community.

Etymology

editThe name Milpitas is the plural diminutive of milpa, Mexican Spanish for "cornfield." The name means "Place of little cornfields."[19] The word milpa is derived from the Nahuatl words milli, meaning "agricultural field," and pan, meaning "on."

The name Milpitas, perhaps used by Jose Maria Alviso to name his land grant, Rancho de las Milpitas, may have meant that there had been small Native American gardens nearby because of the rich alluvial soils of the area.[19]

The first deed of property sale in Milpitas is found in the Santa Clara County Records General Index 1850–1856 (K-143) and is dated February 14, 1856. It is Juana Galindo Alviso, widow of Jose Maria Alviso, to Michael and Ellen Hughes for 800 acres (3.2 km2) of land, today the Main Street area south of Carlo Street, although the deed gives the name of the Rancho as Rancho San Miguel, rather than as Milpitas.

Geography

editMilpitas lies in the northeastern corner of the Santa Clara Valley, which is south of San Francisco. Milpitas is generally considered to be a San Jose suburb in the South Bay, a term used to denote the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.6 sq mi (35.3 km2). 13.6 sq mi (35.2 km2) of it is land and 0.050 sq mi (0.13 km2) of it (0.36%) is water.

The median elevation of Milpitas is 19 feet (5.8 m). At Piedmont Road, Evans Road, and North Park Victoria Drive, the elevation is generally about 100 feet (30 m), while the western area is almost at sea level. The highest point in Milpitas is a 1,289-foot (393 m) peak in the southeastern foothills.

To the east of Milpitas is a range of high foothills and mountains, part of the Diablo Range which runs along the east side of San Francisco Bay. Monument Peak is a prominent summit in the eastern Milpitas hills, and is the location of antenna broadcasting television stations KICU and KQEH to the San Francisco Bay Area.

There are also many creeks in Milpitas, most of which are part of the Berryessa Creek watershed. Calera Creek, Arroyo de los Coches, Penitencia Creek and Piedmont Creek are some of the creeks that flow from the Milpitas hills and empty into the San Francisco Bay. (See Berryessa Creek)

Urban layout

editMilpitas is divided into three sections by Interstates 680 and 880. To the west of I-880 is a largely industrial and commercial area. Between I-880 and its eastern counterpart freeway, I-680, is an industrial zone in the south and residential neighborhoods in the north. Other residential neighborhoods and undeveloped mountains lie east of I-680.

In reality, Milpitas has no concentrated downtown "center," but instead has several small retail centers generally located near residential developments and anchored by a supermarket. The so-called "Midtown" area, the oldest part of Milpitas, has few remaining historic residences and was the only commercial district that existed before 1945. Midtown is situated in the region where Main and Abel Streets run parallel to each other bordered by Montague Expressway in the south and Weller Street at the north end. A USPS post office, Saint John the Baptist Catholic Church, Elementary & Junior High Catholic School, the Milpitas Public Library (which incorporates the old Milpitas Grammar School building), the Smith/DeVries mansion, the Senior Center, and Elmwood Correctional Facility are all in the Midtown section of Milpitas. The Milpitas Civic Center, which includes City Hall, is not located in Midtown, but stands at the intersection of Milpitas and Calaveras Boulevards. The Civic Center is separated from Midtown by the Calaveras overpass. The boundaries that divide major Milpitas neighborhoods and districts include Calaveras Boulevard running from east to west and the Union Pacific railroad, which runs from north to south. The newest retail centers are west of Interstate 880.

Berryessa Creek flows through Milpitas.

Pollution

editMilpitas occasionally experiences odorous air traveling downwind from bay salt marshes, from the Newby Island landfill, from the anaerobic digestion facility at Zero Waste Energy Development Company, and from the San Jose sewage treatment plant's percolation ponds. Most malodorous during the autumn, it is especially pungent west of Interstate 880 because of its close location to the San Francisco Bay and the direction of the prevailing winds out of the north-northwest. The City of Milpitas would like to remedy this air quality problem to the extent it can and encourages its residents to file odor complaints.[20]

Local creeks and the nearby San Francisco Bay suffer somewhat from water pollution originating from street water runoff and industrial wastes. The creeks in Milpitas, especially Calera, Scott, and Berryessa Creeks, used to be prime fishing spots for native steelhead until pollutants from urban development and industry killed the fish starting in the 1950s. While small populations of steelhead and even salmon still may be seen in area streams these cannot legally be fished and consumption of legal catches is limited by mercury contamination.

The I-880 corridor has experienced relatively elevated levels of air pollution from freeway traffic. For example, eight-hour standards for carbon monoxide have been near to maximum levels for the last two decades.[21]

Climate

editSet within a warm Mediterranean climate zone in Santa Clara County, Milpitas enjoys warm, sunny weather with few extreme temperatures. Rainfall is confined mostly to the winter months. During winter, temperatures are relatively cold, at an average of 41 to 59 °F (5 to 15 °C). Showers and cloudy days come and go during this season, dropping most of the city's annual 15 inches (380 mm) of precipitation, and as spring approaches, the gentle rains gradually dwindle. In summer, the grasslands on the hillsides dehydrate rapidly and form bright, golden sheets on the mountains set off by stands of oak. Summer is dry and warm but not hot like in other parts the Bay Area. Temperatures infrequently reach over 100 °F (38 °C), with most days in the low 80s to the mid 80s. From June to September, Milpitas experiences little rain, and as autumn approaches, the weather gradually cools down. Many temperate-climate trees drop their leaves during fall in the South Bay but the winter temperature is warm enough for evergreens like palm trees to thrive.

| Climate data for Milpitas, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

81 (27) |

89 (32) |

95 (35) |

101 (38) |

109 (43) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

109 (43) |

106 (41) |

85 (29) |

79 (26) |

109 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

63 (17) |

68 (20) |

72 (22) |

76 (24) |

82 (28) |

84 (29) |

84 (29) |

82 (28) |

75 (24) |

65 (18) |

58 (14) |

72 (22) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 41 (5) |

44 (7) |

46 (8) |

48 (9) |

53 (12) |

56 (13) |

58 (14) |

58 (14) |

56 (13) |

50 (10) |

45 (7) |

40 (4) |

50 (10) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 24 (−4) |

26 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

35 (2) |

37 (3) |

42 (6) |

47 (8) |

47 (8) |

42 (6) |

36 (2) |

21 (−6) |

19 (−7) |

19 (−7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.03 (77) |

2.84 (72) |

2.69 (68) |

1.02 (26) |

0.44 (11) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.06 (1.5) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.87 (22) |

1.73 (44) |

2.00 (51) |

15.08 (383) |

| Source: [22] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 6,572 | — | |

| 1970 | 26,561 | 304.2% | |

| 1980 | 37,820 | 42.4% | |

| 1990 | 50,686 | 34.0% | |

| 2000 | 62,698 | 23.7% | |

| 2010 | 66,790 | 6.5% | |

| 2020 | 80,273 | 20.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23] | |||

2020

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[24] | Pop 2010[25] | Pop 2020[26] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 14,917 | 9,751 | 7,795 | 23.79% | 14.60% | 9.71% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 2,187 | 1,836 | 1,577 | 3.49% | 2.75% | 1.96% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 240 | 137 | 100 | 0.38% | 0.21% | 0.12% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 32,281 | 41,308 | 57,260 | 51.49% | 61.85% | 71.33% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 347 | 316 | 319 | 0.55% | 0.47% | 0.40% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 131 | 93 | 332 | 0.21% | 0.14% | 0.41% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 2,178 | 2,109 | 2,304 | 3.47% | 3.16% | 2.87% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 10,417 | 11,240 | 10,586 | 16.61% | 16.83% | 13.19% |

| Total | 62,698 | 66,790 | 80,273 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010

editThe 2010 United States Census[27] reported that Milpitas had a population of 66,790. The population density was 4,896.5 inhabitants per square mile (1,890.5/km2). The racial makeup of Milpitas was 13,725 (20.5%) White, 1,969 (2.9%) African American, 309 (0.5%) Native American, 41,536 (62.2%) Asian, 346 (0.5%) Pacific Islander, 5,811 (8.7%) from other races, and 3,094 (4.6%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 11,240 persons (16.8%).

The Census reported that 64,092 people (96.0% of the population) lived in households, 104 (0.2%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 2,594 (3.9%) were institutionalized.

There were 19,184 households, out of which 8,616 (44.9%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 12,231 (63.8%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 2,279 (11.9%) had a female householder with no husband present, 1,105 (5.8%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 760 (4.0%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 100 (0.5%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 2,470 households (12.9%) were made up of individuals, and 742 (3.9%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.34. There were 15,615 families (81.4% of all households); the average family size was 3.61.

The population was spread out, with 15,303 people (22.9%) under the age of 18, 5,887 people (8.8%) aged 18 to 24, 21,827 people (32.7%) aged 25 to 44, 17,434 people (26.1%) aged 45 to 64, and 6,339 people (9.5%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36.1 years. For every 100 females, there were 104.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 104.6 males.

There were 19,806 dwelling units at an average density of 1,452.0 per square mile (560.6/km2), of which 12,825 (66.9%) were owner-occupied, and 6,359 (33.1%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.2%; the rental vacancy rate was 3.1%. 42,501 people (63.6% of the population) lived in owner-occupied dwelling units and 21,591 people (32.3%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

editAs of the census[28] of 2000, there were 62,698 people,[29] 17,132 households, and 13,996 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,785.2 people/km2 (4,624 people/sq mi). There were 17,364 housing units at an average density of 494.4 units/km2 (1,280 units/sq mi). The racial makeup of the city was 51.81% Asian, 30.87% White, 3.66% African American, 0.62% Native American, 0.63% Pacific Islander, 7.48% from other races, and 4.94% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 16.61% of the population.

There were 17,132 households, out of which 43.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 65.1% were married couples living together, 10.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 18.3% are nonfamilies. 11.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 2.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.47, and the average family size was 3.72.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 24.6% under the age of 18, 9.5% from 18 to 24, 38.0% from 25 to 44, 20.9% from 45 to 64, and 7.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there are 110.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 111.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $84,429, and the median income for a family was $84,827 (these figures had risen to $85,186 and $91,232 respectively as of a 2007 estimate[30]). Males had a median income of $51,316 versus $36,681 for females. The per capita income for the city was $27,823. About 3.3% of families and 5.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.5% of those under age 18 and 6.4% of those age 65 or over.[31]

Economy

editMilpitas has a relatively large percent of residents employed in the computer and electronic products industry. 34.1% of men[32] and 26.9% of women[33] are employed in this industry.

While over 75% of people who live in Milpitas work out of the city; the daytime population of Milpitas actually increases by nearly 20% as there are more people living in other cities who work in Milpitas than people living in Milpitas who work in other cities.[34] This results in heavy traffic commutes along key arterial roads twice each day.[35]

Milpitas is home to the headquarters of Adaptec, Aerohive Networks, FireEye, Intersil, SonicWall, IXYS Corporation, Viavi Solutions and Lumentum Holdings (formerly JDSU), KLA-Tencor, Linear Technology, LTX-Credence, SCA, Sigma Designs, and Flex. Many other companies have corporate offices in Milpitas including Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Western Digital, Cisco Systems, Renesas, Infineon Technologies, Varian Medical Systems, Teledyne, Quantum, LifeScan and International Microsystems Inc.

Milpitas is also home to one of Santa Clara County's two correctional facilities, the Elmwood Correctional Facility,[36] which houses over 3,000 inmates.[37]

Top employers

editAccording to the city's 2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[38] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cisco Systems | 3,347 |

| 2 | KLA Corporation | 2,223 |

| 3 | Flex | 2,732 |

| 4 | Sandisk | 1,913 |

| 5 | Linear Technology | 1,283 |

| 6 | Milpitas Unified School District | 811 |

| 7 | Headway Technologies | 735 |

| 8 | FireEye | 528 |

| 9 | Walmart | 439 |

| 10 | Kaiser Permanente Medical Offices | 361 |

Arts and culture

editMilpitas residents enjoy various visual and performing arts. The Milpitas Alliance for the Arts, founded in 1997, is an organization which promotes and funds murals, plays, sculptures, and many other forms of art. The "Art in Your Park" project has put many sculptures in local Milpitas parks, including a ceramic tower in Hillcrest Park, a sundial in Augustine Park, and a historical memorial in Murphy Park. The Celebrate Milpitas Festival is held annually every August, featuring vendors of crafts-type merchandise and providing local talent with a performance venue while selling visitors samplings of exotics like garlic fries or lumpia and even offerings from one or two Californian wineries. The suburb offers a rich variety of food options, including sit-down restaurants and fast food.

The Santa Clara County Library system operates the Milpitas public library.[39]

Retail

editMilpitas is home to the largest Bay Area enclosed shopping mall (in terms of land area), the Great Mall of the Bay Area. The Great Mall is a part of the Simon Property Group and is the biggest mall/outlet shopping center in northern California. There are approximately 200 stores in the mall, with a total of 1,357,000 square feet (126,100 m2) of retail area.

Milpitas is also home to the first and largest power center in Santa Clara County, McCarthy Ranch Marketplace, which was built in 1994.

A large outdoor shopping center called Milpitas Square is west of Interstate 880. Another shopping center in Milpitas is The Seasons Marketplace. Other Milpitas shopping centers and plazas include Ulferts Center, Milpitas Town Center, Jacklin Square, Parktown Plaza, Beresford Square, and the City Square.

In the past, Milpitas had a very different culture from that of its modern suburban state. As late as the 1950s, Milpitas was an unincorporated rural town with the Midtown district on Main Street as its main center of business and social activities. Many old businesses include Main Street Gas (operated by the Azorean Spangler brothers), Smith's Corner Saloon, and Kozy Kitchen. The Cracolice Building was one of the oldest commercial buildings in Milpitas and was the site of many political conventions and meetings. "As Milpitas Goes, So Goes the State" used to be a popular slogan around the town. Most of the land now within modern-day Milpitas's boundaries was used for strawberry, asparagus, apricot, and potato cultivation until the postwar boom during the 1950s and 1960s.

Parks and recreation

editThe city has many athletic and educational recreational programs which are located in several city buildings, including the city's sports center, teen center, library, community center, and senior center.

Parks

editEd R. Levin County Park is the largest county regional park near Milpitas. The County of Santa Clara Parks and Recreation Department runs the park. Monument Peak can be accessed through trails that lead north through the county park. The park also provides facilities for hang gliding and paragliding and includes a newly built dog park that was a joint effort by the county and the city of Milpitas. Two golf courses, Spring Valley Golf Course and Summitpointe Golf Course, are located in the Milpitas foothills. Both have expensive gated residential developments located adjacent to them. Milpitas itself has 17 traditional neighborhood parks which are generally 3 to 10 acres (12,000 to 40,000 m2). There also is a sports complex with two swimming pools and sports parks with baseball and tennis play areas fenced off. There are also smaller parks of less than 3 acres (12,000 m2) scattered in newer developments. Milpitas has begun to develop the San Francisco Water District's Hetch Hetchy right-of-way as park land in lieu of using land from new high density residential developments adjacent to it. Together, these parks total 166 acres (670,000 m2) of land area or less than 2% of the city's acreage. The Milpitas City Council voted February 16, 2016, to designate Jacaranda mimosifolia as Milpitas's official city tree.[40]

Government

editLocal

editThe city has a Council–manager government headed by five-member city council consisting of a mayor, a vice mayor, and three councilmembers. As of April 26, 2024, the mayor is Carmen Montano, the vice mayor is Evelyn Chua, and the councilmembers are Hon Lien, Garry Barbadillo and Anthony Phan. The city manager is Steven McHarris. The city attorney is Christopher Diaz. The police chief is Armando Corpuz. The fire chief is Brian Sherard.

The Milpitas Town Seal was the idea of former Councilman and Vice Mayor John McDermott, who came up with the idea for a seal of the Minuteman from one of his son's history textbooks. He designed the seal and took it to Arnie's Signs and had 4,000 decals made.[41] The city's seal shows Daniel Chester French's Minuteman statue, musket in hand, standing in the Santa Clara Valley, with the golden hills of Milpitas rising to the east. He faces defiantly south toward San Jose because early residents of Milpitas considered themselves minutemen when they defeated efforts by San Jose to annex the newly incorporated Milpitas.

State and federal

editIn the California State Legislature, Milpitas is in the 10th Senate District, represented by Democrat Aisha Wahab, and in the 25th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Ash Kalra.[42]

In the United States House of Representatives, Milpitas is in California's 17th congressional district, represented by Democrat Ro Khanna.[43]

Milpitas Vs. San Jose

editIn 2015, the city of Milpitas challenged a decision by the city of San Jose to expand the Newby Island landfill on the border of the two cities. Residents of Milpitas have complained about the smell of the landfill, which is located underneath a highway leading to San Jose and Fremont. The courts upheld San Jose's position and approved the expansion.[44]

In 2016, Republic Services, owner of the Newby Island landfill, settled a class-action lawsuit over the alleged landfill odor pollution. Republic will create a $1.2 million fund to be paid to households within a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) radius from the landfill. In addition, Republic agreed to provide $2 million to mitigate odors over the next five years. Odor mitigation will include updating the gas collection system and also modifying the composting operation to use forced air static piles.[45][46]

Education

editPrimary and secondary schools

editFrom 1912 to 1956, students attended Milpitas Grammar School—now a city library.[47] Additional schools were built, administered by the Milpitas Elementary School District.[47][48] In 1968, the community voted to combine the city schools as part of the Milpitas Unified School District.[47] District schools include:[49]

- Burnett Elementary

- Calaveras Hills High School

- Curtner Elementary

- Milpitas Adult Education

- Milpitas High School

- Milpitas Middle College High School

- Mattos Elementary

- Pomeroy Elementary

- Rancho Middle School

- Randall Elementary

- Rose Elementary

- Russell Middle School

- Sinnott Elementary

- Spangler Elementary

- Weller Elementary

- Zanker Elementary

Infrastructure

editRoads

editFrom north to south, the major east–west roads in Milpitas are Dixon Landing Road, Jacklin Road, Calaveras Boulevard, and Landess Avenue/Montague Expressway. From east to west, the major north–south roads are Piedmont Road, Evans Road, Park Victoria Drive, Milpitas Boulevard, Main Street, Abel Street, and McCarthy Boulevard. Milpitas roads that reach into the hills are, from north to south, Country Club Drive, Old Calaveras Road, Calaveras Road, and a private ranch drive, the historic Urridias Ranch Road.

As with many other Californian suburbs, Milpitas has divided roads that are maintained well by the local city government. Street signs are in green. Like the San Jose public works system, all pedestrians must manually press a button in order to turn the pedestrian signal lights on (unlike the South Bay cities, San Francisco has automatic pedestrian lights at intersections and does not have "press to cross" buttons for pedestrians).

Not all streets in Milpitas have bicycle lanes or sidewalks. It has a walk score of 48.[50] Piedmont Road, Evans Road, and Jacklin Road have excellent bike lanes and sidewalks with ample spacing, but Montague Expressway and South Milpitas Boulevard have limited sidewalks and narrow bike lanes, which causes some problems for workers commuting by bike or on foot.

Interstate 680 and Interstate 880 lead north to Fremont and south to downtown San Jose. State Route 237 begins at Milpitas and goes west to Sunnyvale and Mountain View.

Public transportation

editThe city is served by the Milpitas BART station, which opened for service as part of Phase I of the Silicon Valley BART extension on June 13, 2020. The station is located near the city limits of San José, and is bounded on two sides by the Montague Expressway and Capitol Ave. A pedestrian bridge runs over Capitol Ave and connects the BART station with VTA's Milpitas light rail station (formerly known as Montague station).[51]

The Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) runs light rail and local buses for public transportation. Three light rail stations lie within city limits: Milpitas, Great Mall, and Alder, all on the Orange Line. VTA bus routes in Milpitas are 46, 47, 60, 66, 70, 71, 77.[52]

The nearest major airport to the city is the San Jose International Airport (SJC), less than ten minutes away in San José. The city is also served by the general aviation Reid–Hillview Airport in East San Jose.

Milpitas borders salt ponds on the San Francisco Bay in the extreme northwest, but has no boat access. Alviso, a neighborhood in San José and formerly a neighboring city, has a marina and boat launch that allows motorized and non-motorized boats access to the bay.

China Airlines formerly operated a bus service to San Francisco International Airport for flights to Taipei, Taiwan.[53]

Communications

editThe USPS post office on Abel Street is Milpitas's main office for postal mail and is the only USPS post office in the city. ZIP code 95035 is exclusively for Milpitas and is the only standard ZIP code for the city. 95036 is a new ZIP that is used sometimes for post office boxes in Milpitas. Until the merger with SBC, Milpitas had relied on Pacific Bell for its telecommunications services. American Telegraph and Telephone (AT&T) acquired Southern Bell (SBC) in 2006 and became the landline telephone provider in the city. As part of the agreement for the merger of AT&T with SBC, Milpitas residents were offered high-speed DSL internet access from AT&T for only $10 per month until December 2009, although few residents were aware of the offer.

On Earth Day, April 22, 2009, the public-private partnership Silicon Valley Unwired announced the rollout of a free municipal WiFi wireless network for the entire city. After the Google WiFi network in Mountain View, it is the second municipal wireless network, providing free Internet access.

Notable people

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

- Kim Bokamper – Miami Dolphins football player

- Brandon Carswell – former USC football player

- Mark Foster – lead singer of Foster the People[54]

- Lenzie Jackson – NFL football player

- Jeannie Mai – TV personality

- Deltha O'Neal – NFL football player

- Tab Perry – NFL football player

- Vita Vea – NFL football player for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers

- Andy Weir – science fiction writer, author of The Martian[55]

In popular culture

editThe Milpitas Monster was filmed in the town in 1976. Originally started as a high school project, it developed into a feature-length film. In the quiet town of Milpitas, California, a gigantic creature is spawned in a polluted, overflowing waste disposal site. The townspeople rally to destroy the creature, which has an uncontrollable desire to consume large quantities of garbage cans.

The movie River's Edge was inspired by the murder of Marcy Renee Conrad in Milpitas in 1981.

John Darnielle's 2022 novel Devil House takes place in Milpitas.

Sister cities

editReferences

edit- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on October 17, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "City Council". City of Milpitas. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Milpitas". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "Milpitas (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "US Census Bureau 2020 QuickFacts: Milpitas, CA".

- ^ Marvin-Cunningham (1990)

- ^ Editors of the Milpitas History Homepage . "The Milpitas History Homepage". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Steve Munzel (January 24, 2003). "Higuera Adobe". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Loomis (1986)

- ^ Steve Munzel (January 24, 2003). "Weller Palm". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Steve Munzel (January 24, 2003). "Maple Hall". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Steve Munzel (January 24, 2003). "Smith's Corners". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Steve Munzel (January 24, 2003). "Kozy Kitchen". Milpitashistory.org. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Devincenzi (2004)

- ^ Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright Publishing. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9781631492860 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Ben Gross (1921–) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". The Black Past. December 11, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Ann Zeise. "How Milpitas Got Its Name". Go Milpitas. Ann Zeise:Go Mipitas!. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Report to the Mayor and City Council on Odor Control in Milpitas January 18, 2011, by: Kathleen Phalen, Utility Engineer

- ^ C. Michael Hogan, Marc Papineau, Ballard George et al., Environmental Assessment of the I880/Dixon Landing Road Interchange Improvement Project, Cities of Fremont and Milpitas, Earth Metrics Incorporated, Federal Highway Administration Publication, March 1989

- ^ "weather.com". Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Milpitas city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Milpitas city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Milpitas city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Milpitas city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Milpitas, California (CA 95035) profile: population, maps, real estate, averages, homes, statistics, relocation, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, moving, houses, news, sex offenders". City-data.com. October 13, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results". Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved May 3, 2009.

- ^ "American Fact Finder". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Top 101 cities with largest percentage of males working in industry: Computer and electronic products (population 5,000+)". City-Data. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ "Top 101 cities with largest percentage of females working in industry: Computer and electronic products (population 5,000+)". City-Data. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ "Milpitas City Statistics". City-Data. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ "Milpitas Community-Based Transportation Plan" (PDF). Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ "Elmwood Jail, Santa Clara County Correctional Facilities". Go Milpitas. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "About Us - Correction, Department of (DEP)". Archived from the original on October 15, 2007.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report : For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020" (PDF). ci.milpitas.ca.gov.

- ^ "Milpitas Library Welcome Page". Archived from the original on December 1, 1998.

- ^ Mohammed, Aliyah (February 24, 2016). "Milpitas: Council approves colorful Jacaranda Mimosifolia tree as official city tree". The Mercury News. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "Milpitas History". Milpitas Historical Society. April 1, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ "California's 17th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ "City of Milpitas v. City of San Jose, H040664 | Casetext Search + Citator". casetext.com. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ "Milpitas: Judge finalizes settlement in class-action suit over alleged landfill odors – The Mercury News". July 25, 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ "Peter Ng, et al. v. International Disposal Corp. of California, et al. - Liddle & Dubin, P.C." www.ldclassaction.com. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c "History". Milpitas Unified School District. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "Milpitas Unified School District" (PDF). California State Treasurer's Office. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Our Schools". Milpitas Unified School District. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "Milpitas neighborhoods on Walk Score". WalkScore.

- ^ "BART finally comes to San Jose Saturday: What you need to know about the new stations". The Mercury News. June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ "Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority". Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.china-airlines.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2005. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Snapchat from Mark Foster on a Fan page". June 2, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ Vallone, Julie (November 2015). ""The Man From Mars"" (PDF). South Bay Accent. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

Bibliography

editThe following books on Milpitas have been used as significant references for this article. Many of the books are not available at a regular store or are out of print, but all are available at the Milpitas branch of the Santa Clara County Library. These books are also recommended as resources for further reading.

- Burrill, Robert L. (2005). Milpitas. Images of America Series. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2910-3.

- Craig, Madge (1976). History of Milpitas: Sketch by Beverly Craig.

- Devincenzi, Robert J.; Thomas Gilsenan; Morton Levine (2004). Milpitas: Five Dynamic Decades. City of Milpitas. ISBN 978-0-9748858-0-3.

- Loomis, Patricia (1986). Milpitas: the century of "little cornfields," 1852-1952. California History Center. ISBN 978-0-935089-07-3.

- Marvin-Cunningham, Judith; Paula Juelke Carr (1990). Historic Sites Inventory, Milpitas, California 1990. City of Milpitas.