Mataquescuintla (from Nahuatl, meaning net to catch dogs) is a town and municipality in the Jalapa department of south-east Guatemala.[2] It covers 262 square kilometres (101 sq mi).[3]

Mataquescuintla | |

|---|---|

Municipality | |

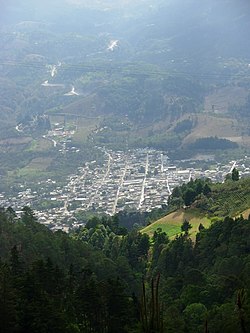

Mataquescuintla seen from Miramundo and Pino Dulce | |

| Coordinates: 14°32′1″N 90°11′2″W / 14.53361°N 90.18389°W | |

| Country | |

| Department | |

| Villa | 1848 |

| Incorporated | 1848 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Body | Mataquescuintla municipal council |

| • Mayor of Mataquescuintla | Hugo Manfredo Loy |

| Area | |

| • Total | 262 km2 (101 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,727 m (5,000 ft) |

| Population (2018 census)[1] | |

| • Total | 41,848 |

| • Density | 160/km2 (410/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 9,833 |

| Demonyms |

|

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central America) |

| Climate | Cwb |

| Website | Mataquescuintla municipality |

Mataquescuintla played a significant role during the first half of the nineteenth century, when it was the center of operations of conservative general Rafael Carrera, who led a Catholic peasant revolution against the liberal government of Mariano Gálvez in 1838, and then ruled Guatemala from 1840 until his death in 1865.

It is divided into 6 zones. [4]

Toponymy

editThe toponym "Mataquescuintla" comes from Nahuatl, and is composed of the words "matatl" (meaning "net bag"), "Itzcuintli" (meaning "dog") and "tlan" (meaning: "abundance"), and means "net to catch dogs".[5]

History

editThe first settlers in Mataquescuintla were Pipils that came from the province of El Salvador.

After Central American independence

editIn the 1825 Constitution of Guatemala, Mataquescuintla was established as part of Cuilapa, in District 3; also in Cuilapa are Los Esclavos, Oratorio, Concepción, La Vega, El Pino, Los Verdes, Los Arcos, Corral de Piedra, San Juan de Arana, El Zapote, Santa Rosa, Jumay, Las Casillas, and Epaminondas.[6]

Overthrow of Mariano Gálvez

editIn 1837, an armed struggle began against the regime of Francisco Morazán, president of the Federal Republic of Central America, a political entity that included Guatemala, Comayagua (later named Honduras), El Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The rebellion also fought against those who governed the State of Guatemala, like Chief of State Mariano Gálvez. The leader of the insurgency was Rafael Carrera; among its forces were numerous natives,[7] since on 9 June 1837, the State of Guatemala had reintroduced indigenous populations that had been suppressed since colonial times by the Cortes of Cádiz. The insurgents began hostilities by means of a guerrilla war: attacking populations without giving them an opportunity to have meetings with government troops. At the same time, Gálvez's clerical enemies spread ideas, accusing him of poisoning river water to spread cholera morbus, which hadn't happened even with the large population growth and the poor health structure in the region. The accusation, however, was beneficial to Carrera, putting a large part of the population against Mariano Gálvez and liberals in general.

Standing out among the battles of Carrera: in the barracks at Mataquescuintla; at Ambelis in Santa Rosa, defeating the army commanded by Teodoro Mejía; on 7 December 1837 in the plaza at Jalapa where he was defeated; and on 13 January 1838 where the Garrison of Guatemala was attacked. Some of these military events were accompanied by robberies, robberies, searches and murders of defenseless people. In particular, the Gálvez government, upon learning that Carrera was the leader of the revolt, invaded Mataquescuintla and captured his wife, Petrona Álvarez, whom the soldiers seized by force. When Carrera heard of this, he vowed to avenge his wife, and newly accompanied by her, restarted the fight with new vigor. Petrona Álvarez, inflamed with the desire for revenge, committed numerous atrocities against the liberal troops, to the point that many of Carrera's coreligionists feared her more than the caudillo himself,[8] although by that time Carrera had already showed his military leadership and expertise that would come to later characterize him.

The fight had taken on the form of holy war, for it was the parish priests of the secular clergy who argued for the peasants to defend religious rights and to fight against the liberal atheists; Carrera had been educated by the parish priest of Mataquescuintla who taught Catholicism and started to worry about the liberals' power. Another factor that influenced the revolt were the concessions given by the liberal government of Francisco Morazán to the English—whom they called "heretics" because they were Protestants. In Guatemala, they had been given Belize and San Jerónimo in Salamá—which was an expensive and profitable property that the liberals had seized from the Dominicans in 1829.[9] The contraband English items from Belize had impoverished the artisan Guatemalans, who joined Carrera's revolt.[10] The priests announced to the natives that Carrera was their protector angel, who had descended from the heavens to take revenge on heretics, liberals, and aliens, and to restore their ancient dominion. They devised various tricks to make the natives believe this, which were announced as miracles. Among them, a letter was thrown from the roof of one of the churches, in the middle of a vast congregation of natives. This letter supposedly came from the Virgin Mary, who commissioned Carrera to lead a revolt against the government.[11]

To counteract the violent attacks made by peasant guerrillas, Gálvez approved and then praised the use of a scorched earth policy against the uprising peoples. Several of his supporters advised him to desist from this tactic, because it would only contribute to increasing hostility.[12] In early 1838, José Francisco Barrundia, the liberal leader of Guatemala, disillusioned with Galvez's management, managed to bring Guatemala City under Carrera's command, and fought the head of state. Later that year, the situation in Guatemala became unsustainable: the economy was paralyzed by the lack of security and roads, and the liberals negotiated with Carrera to end the warring. Gálvez left power 31 January 1838, before an "Army of the People", giving control to Rafael Carrera that initiated the battle in Guatemala City with an army of between ten thousand and twelve thousand men, after the agreement left Carrera against Barrundia.

Carrera's troops victorious, they shouted "Long live religion!" and "Away with foreign heretics!" Consisting mainly of poorly armed peasants, they took Guatemala City by force pillaged and destroyed the liberal government buildings, including the Archbishop's Palace, where Gálvez had resided, and the house of the English presenter William Hall.[10] On 2 March 1838, Gálvez's absence was unanimously accepted in Congress, and after a period of uncertainty, Rafael Carrera came to power, although first would suffer some defeats.

Creation of Santa Rosa department

editThe Republic of Guatemala began under President General Rafael Carrera on 21 March 1847 so that the former State of Guatemala could freely trade with foreign nations.[15] On 25 February 1848, the Mita region was separated from the department of Chiquimula, into its own department, and divided into three districts: Jutiapa, Santa Rosa and Jalapa.[16] The Santa Rosa department included Santa Rosa as the capital, and Cuajiniquilapa, Chiquimulilla, Guazacapán, Taxisco, Pasaco, Nancinta, Tecuaco, Sinacantán, Isguatán, Sacualpa, La Leona, Jumay and Mataquescuintla.[16]

After the Liberal Revolution

editAfter the Liberal Revolution of 1871, liberals began to negatively recount the Carrera regime.[17][18][19] The role of Mataquescuintla in the formation of the Republic of Guatemala was set aside by liberal historians, such as José María Bonilla, Ramón Rosa,[18] Lorenzo Montúfar y Rivera and Ramón A. Salazar.[19]

In 1889, Mataquescuintla was scene of an uprising led by colonel Hipólito Ruano against the government of general Manuel Lisandro Barillas Bercián. Opposing policies set up Barillas, Ruano and other retired soldiers rose up in arms, and quickly stopped by the government.[20] Ruano was captured and shot in Mataquescuintla Square.[21]

On 3 September 1935, Mataquescuintla left the department of Santa Rosa and was incorporated in the department of Jalapa. On 29 October 1850 the village was elevated to become a town.[22]

Government

editThe municipalities are regulated by various laws of the Republic, which establish their form of organization, administrative bodies, and their taxes. Although they are autonomous entities, they are subject to national legislation and the main laws that govern them since 1985 are:

| No. | Law | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Constitution of Guatemala | Contains specific legal regulations for municipalities in articles 253 to 262. |

| 2 | Electoral Law of Policital Parties | Constitutional law applicable to municipalities via their elected officials. |

| 3 | Municipal Code | Decree 12-2002 of the Congress of Guatemala. It is ordinary law and is applicable to all municipalities, and contains legislation regarding the creation of municipalities. |

| 4 | Municipal Service Law | Decree 1-87 of the Congress of Guatemala. Regulates the relations between the municipality and public servants in labor matters. It has its constitutional basis in article 262, that orders an issuance of the same. |

| 5 | General Decentralization Law | Decree 14-2002 of the Congress of Guatemala. It regulates the constitutional authority of the State, and therefore of the municipality, to promote and apply decentralization, both economic and administrative. |

The municipal government is in charge of a Municipal Council[23] while the municipal code—an ordinary law containing provisions that apply to all municipalities—establishes that "the municipal council is the highest collegiate body for deliberation and decision of the municipalities ... and has its seat in the district of the principal municipality"; article 33 of the aforementioned code establishes that "it is the exclusive responsibility of the municipal council to exercise the government of the municipality."[24]

The municipal council works with the mayor, the trustees, and councilors, and is elected directly for a period of four years, and can be re-elected.[23][24] There are also Auxiliary Community Development Committees (COCODE), Municipal Development Committee (COMUDE), as well as cultural associations and work commissions. Auxiliary mayors are elected by the communities according to their own set of principles and traditions, and meet with the municipal mayor on the first Sunday of each month, while the Community Development Committees and the Municipal Development Committee organize and facilitate the participation of the community's prioritizing needs and problems. The mayor from 2012 to 2016 was Hugo Manfredo Loy.[25]

Geography

editClimate

editMataquescuintla has a Köppen climate classification of Cwb.

| Climate data for Mataquescuintla | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22.9 (73.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

24.1 (75.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

20.2 (68.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.9 (66.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 12.5 (54.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

14.7 (58.5) |

14.7 (58.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.4 (57.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

13.8 (56.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 8 (0.3) |

10 (0.4) |

18 (0.7) |

42 (1.7) |

192 (7.6) |

319 (12.6) |

243 (9.6) |

238 (9.4) |

301 (11.9) |

194 (7.6) |

41 (1.6) |

15 (0.6) |

1,621 (64) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[26] | |||||||||||||

Location

editIt is located north of San Rafael Las Flores, Casillas, Santa Rosa de Lima and Nueva Santa Rosa in Santa Rosa, east of San José Pinula in Guatemala Department, west of San Carlos Alzatate in Jalapa, and south of Sansare in El Progreso and Palencia in Guatemala Department.[27] It is very near Ayarza Lagoon and an abandoned bismuth mine.

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Citypopulation.de Population of departments and municipalities in Guatemala

- ^ Escalante Herrera 2007.

- ^ Cuyán Tahuite 2005.

- ^ a b Woodward 1993.

- ^ Rivera Natareno 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Pineda de Mont 1869, p. 467.

- ^ Hernández de León 1930, p. 63.

- ^ González Davison 2008, p. 48.

- ^ González Davison 2008, p. 42.

- ^ a b González Davison 2008, p. 52.

- ^ Squier 1852, p. 429-430.

- ^ González Davison 2008, p. 51.

- ^ Woodward 2002.

- ^ González Davison 2008.

- ^ Pineda de Mont 1869, pp. 73–76.

- ^ a b Pineda de Mont 1869, p. 477.

- ^ González Davison 2008, p. 426 "Lo que los liberales consideraban como desarrollo, consistía en la expropiación de las tierras de indios y de la Iglesia -que Carrera protegió por sobre todo durante su gobierno- y el uso de los campesinos como mano de obra gratuita para ser utilizadas para el cultivo de café a gran escala -lo que fue legalizado por el liberal Justo Rufino Barrios con su reglamento de jornaleros"

- ^ a b Rosa 1974.

- ^ a b Montúfar & Salazar 1892.

- ^ Revista Militar 1899, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Revista Militar 1899, p. 190.

- ^ García Orellana 2005, p. 2.

- ^ a b Asamblea Constituyente 1985.

- ^ a b Congreso de Guatemala 2012.

- ^ Prensa Libre 2011.

- ^ "Climate: Mataquescuintla". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ "Monografía del municipio de Mataquescuintla" (PDF). Municipalidad de Mataquescuintla (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

Bibliography

edit- Asamblea Constituyente (1985). Constitución Política de la República de Guatemala (PDF) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Gobierno de Guatemala. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Congreso de Guatemala (2012). Código Municipal de Guatemala (PDF) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Gobierno de Guatemala. Archived from the original on 2015-08-07.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Cuyán Tahuite, Maritza Nohemí (2005). Diagnóstico socieconómico, potencialidades productivas y propuestas de inversión. Municipio de Mataquescuintla, departamento de Jalapa (PDF) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Comercialización (Panadería). Archived from the original on 2016-03-04 – via Ejercicio profesional supervisado.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Escalante Herrera, Marco Antonio (2007). "Breve información sobre Mataquescuintla". Pbase.com (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on 2010-02-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Fuentes y Guzmán, Francisco Antonio de (1883) [1690]. Zaragoza, Justo; Navarro, Luis (eds.). Recordación Florida. Discurso historial y demostración natural, material, militar y política del Reyno de Guatemala (in Spanish). Vol. II. Madrid, España: Central.

- García Orellana, Maria (2005). "Diagnóstico socieconómico, potencialidades productivas y propuestas de inversión. Municipio de Mataquescuintla, departamento de Jalapa" (PDF). Ejercicio profesional supervisado (in Spanish). Vol. 3. Guatemala: Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Archived from the original on 2015-01-01.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - González Davison, Fernando (2008). La montaña infinita; Carrera, caudillo de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Artemis y Edinter. ISBN 978-84-89452-81-7.

- Hernández de León, Federico (29 January 1959). "El capítulo de las efemérides: Reconquista del Estado de los Altos". Diario la Hora (in Spanish).

- Hernández de León, Federico (27 February 1959). "El capítulo de las efemérides: Caída del régimen liberal de Mariano Gálvez". Diario la Hora (in Spanish). Guatemala.

- Hernández de León, Federico (16 March 1959). "El capítulo de las efemérides: Segunda invasión de Morazán". Diario la Hora (in Spanish). Guatemala.

- Hernández de León, Federico (20 April 1959). "El capítulo de las efemérides: Golpe de Estado de 1839". Diario la Hora (in Spanish). Guatemala.

- Hernández de León, Federico (21 April 1959). "El capítulo de las efemérides: Muerte de Carrera". Diario la Hora (in Spanish). Guatemala.

- Hernández de León, Federico (1930). El libro de las efemérides (in Spanish). Vol. III. Guatemala: Tipografía Sánchez y de Guise.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) (2002). "XI Censo Nacional de Poblacion y VI de Habitación (Censo 2002)". Ine.gob.gt (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on 24 August 2008.

- Montúfar, Lorenzo; Salazar, Ramón A. (1892). El centenario del general Francisco Morazán (in Spanish). Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional.

- Pineda de Mont, Manuel (1869). Recopilación de las leyes de Guatemala, 1821-1869 (in Spanish). Vol. I. Guatemala: Imprenta de la Paz en el Palacio.

- Prensa Libre (2011). "Ganadores del poder local en las elecciones de Guatemala 2011" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- Revista Militar (15 May 1899). "El coronel don Hipólito Ruano". Revista Militar: órgano de los intereses del Ejército (in Spanish). I (12). Guatemala.

- Rivera Natareno, Claudia Virginia (2005). "Diagnóstico socieconómico, potencialidades productivas y propuestas de inversión. Municipio de Mataquescuintla, departamento de Jalapa" (PDF). Ejercicio profesional supervisado (in Spanish). Vol. 1. Guatemala: Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Rosa, Ramón (1974). Historia del Benemérito Gral. Don Francisco Morazán, ex Presidente de la República de Centroamérica (in Spanish). Tegucigalpa: Ministerio de Educación Pública, Ediciones Técnicas Centroamericana.

- Squier, Ephraim George (1852). Nicaragua, its people, scenery, monuments and the proposed Interoceanic Canal. New York: D. Appleton and Co.

- Stephens, John Lloyd; Catherwood, Frederick (1854). Incidents of travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan. London: Arthur Hall, Virtue and Co.

- Taracena, Arturo (1999). Invención criolla, sueño ladino, pesadilla indigena, Los Altos de Guatemala: de región a Estado, 1740-1871 (in Spanish). Guatemala: CIRMA. Archived from the original on 2016-01-09. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- Woodward, Ralph Lee Jr. (2002). Rafael Carrera y la creación de la República de Guatemala, 1821–1871 (in Spanish). CIRMA y Plumsock Mesoamerican Studies. ISBN 0-910443-19-X. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Woodward, Ralph Lee (1993). Rafael Carrera and the Emergence of the Republic of Guatemala, 1821-1871. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.