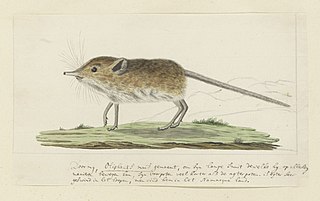

The round-eared elephant shrew (Macroscelides proboscideus) or round-eared sengi (called the Karoo round-eared elephant shrew to distinguish it from its sister species;[2] formerly misleadingly named the "short-eared elephant shrew"),[3] is a species of elephant shrew (sengi) in the family Macroscelididae. It is found in Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical dry shrubland, and grassland, and hot deserts.[1] They eat insects, shoots, and roots. Their gestation period is 56 days.[4]

| Macroscelides proboscideus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Macroscelidea |

| Family: | Macroscelididae |

| Genus: | Macroscelides |

| Species: | M. proboscideus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Macroscelides proboscideus (Shaw, 1800)

| |

| |

| Geographic range | |

Elephant shrews are among only a handful of monogamous mammals, making them a model group for the study of monogamy. They have been studied for their mate guarding behavior.[5] Mate guarding is considered a predominant male trait in round-eared elephant shrews. This strategy is used to guard the female before and after heat to eliminate male competition, which makes male round-eared elephant shrews monogamous and more vulnerable to their surroundings as they spent a majority of their time dedicated to this tactic. [6]

Research was recently conducted to determine that elephant shrews are thought to have dichromatic color vision due to their ability to differentiate between blue/green colors and grey. However, there is no evidence to prove that the species can see red colors. [7]

Habitat

editThe round-eared elephant shrew are native to Southeast Africa where the temperature ranges from 18°C to 6°C in the winter and 30°C to 22°C during the summer.

Foraging and diet

editRound-eared elephant shrews are omnivores with their diet mainly consisting of insects and supplemented with plants. During the winter, this species consumes less insects than they do during the summer due to a decrease in the insect population.

Reproduction and life cycles

editThe round-eared elephant shrew does not reproduce during the winter.

References

edit- ^ a b Rathbun, G.B.; Smit-Robinson, H. (2015). "Macroscelides proboscideus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T45369602A45435551. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T45369602A45435551.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Dumbacher, J. P.; Rathbun, G. B.; Smit, H. A.; Eiseb, S. J. (2012). Steinke, Dirk (ed.). "Phylogeny and Taxonomy of the Round-Eared Sengis or Elephant-Shrews, Genus Macroscelides (Mammalia, Afrotheria, Macroscelidea)". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e32410. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732410D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032410. PMC 3314003. PMID 22479325.

- ^ Rathbun, G. H. (2005). "Order Macroscelidea". In Skinner, J. D.; Chimimba, C. T. (eds.). The Mammals of the Southern African Sub-region. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0521844185.

- ^ California Academy of Sciences. Elephant-shrews or Sengis: Macroscelidea. "Elephant-Shrews". Archived from the original on 2008-07-23. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ Bernard, R. T. F., G. I. H. Kerley, T. Doubell and A. Davison 1996. Reproduction in the round-eared elephant shrew (Macroscelides proboscideus) in the southern Karoo, South Africa. Journal of Zoology, London, 240 233-243.

- ^ Schubert, Melanie; Schradin, Carsten; Rödel, Heiko G.; Pillay, Neville; Ribble, David O. (2009-12-01). "Male mate guarding in a socially monogamous mammal, the round-eared sengi: on costs and trade-offs". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 64 (2): 257–264. doi:10.1007/s00265-009-0842-2. ISSN 1432-0762. S2CID 44029280.

- ^ Thus, Patricia (16 Sep 2020). "Colour vision in sengis (Macroscelidea, Afrotheria, Mammalia): choice experiments indicate dichromatism". Behaviour. 157 (14–15): 1127–1151. doi:10.1163/1568539x-bja10039. S2CID 224945580. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

External links

edit

- ^ Lawes, M. J., and M. R. Perrin. “Risk-Sensitive Foraging Behaviour of the Round-Eared Elephant Shrew (Macroscelides Proboscideus).” Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, vol. 37, no. 1,25 Feb. 1995, pp. 31–37., https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00173896.