The Lynch Expedition (Spanish: Expedición Lynch) was a series of raids during the War of the Pacific on the Peruvian coast north of Lima. It was conducted by Patricio Lynch, Captain of the Navy of Chile. Beginning on 4 September 1880 and continuing for two months,[1] Lynch sailed north from Arica, and over the course of his raids, he captured resources and destroyed 4.7 million US dollars worth of Peruvian property.

Background edit

By June 1880, Peru had lost the economic resources and the manpower it required to continue the War of the Pacific. However, the Peruvian president, Nicolás de Piérola, urged the war to continue, promising to resist "to the last bullet". The Chileans, too, felt the urge to continue the fight, and so they planned to attack the Peruvian capital of Lima. However, while the Chilean forces were preparing for the attack on Lima, they had to find a way to keep their morale and their martial skills up.[2]

Following the fall of the city of Arica, Chilean Captain of the Navy Patricio Lynch contacted Chilean president Aníbal Pinto about the possibility to conduct a raid on the coast of northern Peru. This raid, he argued, would keep the fighting edge and the morale of the soldiers high, put pressure on Piérola to divert his forces from the south, collect taxes for Chile, and hopefully convince the Peruvian upper class to abandon the war. Pinto accepted, authorizing the request in August 1880, with the Chilean government officially authorizing it in September.[3]

Pinto only accepted Lynch's proposal for an expedition under the conditions that he would not tax anything that does not give direct profit to the government, that he would only destroy something if its owner refused to pay a tax, that "arson or vandalic destruction" was forbidden, and that neutral property could not be harmed. Property ownership problems were put under a specially-appointed attorney named Daniel Carrasco Albano.[4]

Expedition edit

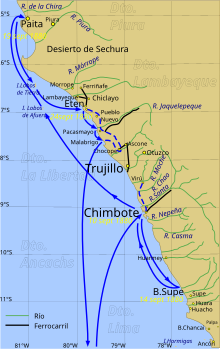

The expedition started on 4 September 1880, when Lynch and 2,600 men[5] of the 1st Line Regiment and the Batallones Colchagua and Talca boarded the Itata and the Copiapó at Arica. Later on, they were joined by the Chacabuco and the O'Higgins.[4] Also among the ships were the Amazonas and the Abtao. On 10 September, the former two ships landed at Chimbote, occupied the plantations of El Puente and Palo Seco[1] as well as the station house and related buildings (belonging to an American named Du Bois)[6] and demanded a payment of 100,000 Peruvian soles from a local landowner named Dionisio Derteano. Derteano chose to not pay, incurring Lynch to attack his plantation of Palo Seco.[7]

The reaction from the Peruvian government was not to move troops, but to warn Peruvians that if they paid money to the Chileans, they would be seen and tried as traitors.[1] In mid-September, Lynch and his men destroyed the Chimbote railroad[8] and the station-house, destroying or disabling locomotives and rolling stock, with damage amounting to 304,398 soles.[9] At this time, he also collected taxes from Lambayeque and Monsefú. To the prefect of Lambayeque, Lynch demanded 150,000 soles.[10] Upon reaching Monsefú, its defender, José M. Aguirre, fled with his men from the Chileans and handed the city over to foreigners. One of these foreigners, a German named Luis Albrecht, gave Lynch 60,000 pesos for him and his men to leave.[11] After leaving Chimbote, having occupied it until the 18th,[9] Lynch sent 400 men to the town of Sepa to intercept a wagon train of munitions, from which they destroyed 200,000 rounds of ammunition. On 22 September Lynch went to Paita, and then to Eten on the 24th, upon which he advanced to Chiclayo on foot.[1]

Freeing the Chinese edit

One of the most notable acts Lynch did during his expedition was his freeing of Chinese coolies (slaves) from Peruvian landowners. The Chinese, who called Lynch the "Red Prince", helped him during the war.[8] Formally, over 1,500 Chinese men worked for Lynch as guides, pontoon bridge builders, and haulers of supplies. Some Chinese were assigned to Arturo Villaroel's special engineer unit, which helped defuse mines and open wells. Lynch was portrayed as a liberator of slaves by Chilean media, which gleefully depicted the release and rage of the Chinese against Peru. Lynch also used the anger of the freed Chinese as leverage.[12]

Aftermath edit

In total, Lynch destroyed 4.7 million US dollars worth of Peruvian property, and took for Chile resources such as food and materials. They also collected money - 7.3 million soles in bank notes, 375,000 dollars in postal stamps, and 11,000 dollars in silver.[8] The expedition also stopped commerce in the area.[13] 10 coastal towns were destroyed.[5]

References edit

Citations edit

- ^ a b c d Farcau 2000, p. 152.

- ^ Sater 2007, pp. 258–59.

- ^ Sater 2007, pp. 259–60.

- ^ a b Sater 2007, p. 260.

- ^ a b Clodfelter 2017, p. 324.

- ^ United States Department of State 1884, p. 109.

- ^ Sater 2007, pp. 260–61.

- ^ a b c Sater 2007, p. 262.

- ^ a b United States Department of State 1884, p. 110.

- ^ Tinsman 2018, p. 445.

- ^ Sater 2007, pp. 261–62.

- ^ Tinsman 2018, pp. 444–45.

- ^ Scheina 1987, p. 36.

General bibliography edit

- Clodfelter, Micheal (24 April 2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015, 4th ed. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-2585-0.

- Farcau, Bruce W. (2000). The Ten Cents War: Chile, Peru, and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96925-7.

- Sater, William F. (1 January 2007). Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-0759-X.

- Scheina, Robert L. (1987). Latin America: A Naval History, 1810-1987. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-295-6.

- Tinsman, Heidi (1 August 2018). "Rebel Coolies, Citizen Warriors, and Sworn Brothers: The Chinese Loyalty Oath and Alliance with Chile in the War of the Pacific". Hispanic American Historical Review. 98 (3). Duke University Press: 439–69.

- United States Department of State (1884). Foreign Relations of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office.