This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (November 2023) |

Juan Gabriel Vásquez (born 1973) is a Colombian writer, journalist and translator. He has written many novels, short stories, literary essays, and numerous articles of political commentary.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez | |

|---|---|

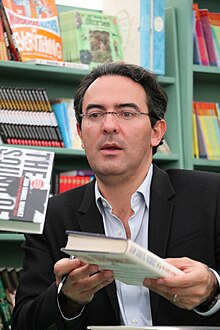

Vásquez at the 2016 Hay Festival | |

| Born | 1973 (age 50–51) Bogotá, Colombia |

| Occupation | Writer, translator, journalist |

| Nationality | Colombian, Spanish |

| Genre | Novel, short story, essay, political commentary |

| Notable awards | Alfaguara de Novela 2011 Prix Roger Caillois 2012 Premio Nacional de Periodismo Simón Bolívar 2007, 2012 Premio Gregor Von Rezzori - Città di Firenze 2013 International Dublin Literary Award 2014 Premio Arzobispo Juan de San Clemente 2014 Premio Real Academia Española 2014 Prémio Casa de América Latina de Lisboa 2016 Prix Carbet des Lycéens 2016 Prémio Literário Casino da Póvoa 2018 Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres 2016 Cruz Oficial de la Orden de Isabel la Católica 2018 |

His novel The Sound of Things Falling, published in Spanish in 2011, won the Alfaguara Novel Prize and the 2014 International Dublin Literary Award, among other prizes. His novels have been published in 28 languages. In 2012, after living in Europe for sixteen years, in Paris, the Belgian Ardennes, and Barcelona, Vásquez moved with his family back to Bogotá.

Biography and literary career

editYouth and studies in Bogotá

editJuan Gabriel Vásquez was born in Bogotá in 1973,[1] to Alfredo Vásquez and Fanny Velandia, both lawyers. He began to write at an early age, publishing his first stories in a school magazine at the age of eight. During his teenage years, he began reading the Latin American writers of the boom generation: Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa and Carlos Fuentes, among others.

In 1990, Vásquez began studying Law at the Universidad del Rosario. The university is located in downtown Bogotá, surrounded by the streets and historical sites where Vásquez’s novels are set. While studying for his law degree, he voraciously read Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortázar, among other Latin American authors, and studied the works of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. He graduated in 1996 with a thesis entitled Revenge as a legal prototype in the Iliad, later published by his alma mater. By the time he received his diploma, he had already decided to pursue a career as a writer.

The Parisian period (1996–1998)

editDays after receiving his diploma, Vásquez traveled to Paris for post-graduate studies in Latin American literature at La Sorbonne, which he never finished. He had literary reasons for choosing Paris, as Vásquez associated the city with the works of expatriate authors who had influenced him: Mario Vargas Llosa, Julio Cortázar, and James Joyce. But he also left Colombia because of the political violence and climate of fear that prevailed in the country since the 1980s.

In Paris, Vásquez finished his first novel, Persona (1997). A short novel set in Florence, it shows the influence of modernism and of Virginia Woolf, an author to whose work Vásquez has always felt close. After his studies at the Sorbonne, Vásquez abandoned writing a thesis in order to concentrate on fiction. He finished a second novel, Alina suplicante in 1999.

Vásquez later repeatedly expressed his dissatisfaction with his first two books, which he thought of as the works of an apprentice. He has refused to reissue them after their initial publication. Both are short novels with an intimate atmosphere, but otherwise have little in common. Vásquez has said that even before publishing Alina suplicante, his dissatisfaction with these works pitched him into a deep crisis. He left Paris at the beginning of 1999, looking for a place to renew himself.[2]

The season in the Ardennes (1999)

edit1999 was a crucial year for Vasquez, both professionally and personally. Between January and September, Vásquez lived near Xhoris, a small town in the Walloon area of Belgium in the home of an older couple in the Ardennes. He has frequently stressed the importance of this period.[3]

His short story "The Messenger" was included in Líneas Aéreas, an anthology that would be regarded as the main forecast of Spanish and Latin American literature in the 21st century. He read the work of novelists who would leave a strong mark on his own work, such as Joseph Conrad and Javier Marías, and also short story writers far from the Latin American tradition, like Chekhov and Alice Munro.[4] His experiences, encounters and observations during that season became the material of his next book, the collection of stories The All Saints’ Day Lovers (2001).

In September 1999, Vásquez married Mariana Montoya. They settled in Barcelona. Vásquez has invoked three reasons for choosing that destination: the link between Barcelona and the Latin American Boom, the opportunities the city offered to someone who wanted to earn a living by his pen, and the open spirit with which the new Latin American literature was being received in Spain.[3]

The Barcelona years (1999–2012)

editIn 2000, Vásquez began working as an editor at Lateral, an independent Barcelona magazine that was published between 1994 and 2006. Under the direction of a Hungarian expatriate, Mihály Dés, the magazine brought together a generation of emerging writers such as French novelist Mathias Énard and Catalan cultural critic Jordi Carrión. The Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño was also connected to the magazine.

While working at Lateral, Vásquez wrote a series of short stories based on his experiences during the years he spent in France and Belgium. Lovers on All Saints’ Day was published in Colombia in April 2001; although it was well received, evoking comparisons to Raymond Carver and Jorge Luis Borges, critics were surprised by the fact that a Colombian author should write a book with Belgian or French characters.[5] The few reviews that appeared in Spain praised the "subtleties of a Central European narrator"[6] and discussed the simultaneous influence of Borges and Hemingway.[7] From then on Vásquez would consider Lovers on All Saints’ Day as his first mature book.

During the early years in Barcelona, Vásquez also worked as a translator. He was commissioned to do the first translation published in Spain of Hiroshima, by John Hersey. In 2002, after leaving Lateral, he concentrated on translation and journalism as ways to earn a living. He wrote articles and book reviews for El Periódico de Catalunya and El País, among others. He translated Victor Hugo’s Last Day of a Condemned Man and John Dos Passos’ Journeys Between Wars. In 2003, Vásquez published Nowhere Man (El hombre de ninguna parte), a brief biography of Joseph Conrad.

The following year, Vásquez published the novel he now regards as his first: The Informers. Its critical reception was extraordinary. The novel was praised by Mario Vargas Llosa and Carlos Fuentes. Semana Magazine, one of the most influential Colombian publications, chose it as one of the most important novels published since 1981. In a few years, it was translated into more than a dozen languages.[8] In England, where it was endorsed by John Banville, it was shortlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. Its publication in the United States in 2009 had an unusual reception for a Latin American writer. In The New York Times, Larry Rohter wrote: "Vasquez's career takes off remarkably."[9] Jonathan Yardley, in The Washington Post, said it was "the best work of literary fiction to come my way since 2005".[10] The novel was translated by Anne McLean, who has subsequently translated all of Vásquez’s books.

In September 2005, his twin daughters Martina and Carlota were born in Bogotá. Vasquez's next novel, The Secret History of Costaguana, is dedicated to them. The novel, built on speculation (Joseph Conrad's possible visit to Colombia in the 1870s), confirmed Vásquez's reputation. He establishes a dialogue with the life and work of Conrad, in particular his novel Nostromo, and with the Colombian history of the 19th century, especially the building of the Panama Canal. His narrator has a picaresque and sarcastic tone, constantly addressing the reader, having recourse to anachronisms, exaggerations, and improbability whenever it suits his yarn. According to Spanish novelists Juan Marsé and Enrique Vila-Matas, Vásquez creates a powerful dialogue between the narrator and the reader, as well as between fiction and history.

The Secret History of Costaguana is also an indirect comment on Vásquez's relationship with the work of Gabriel García Márquez. It is an issue to which he has returned many times discussing the idea of influence. In one of his articles he wrote:

That right to mix traditions and languages with impunity - to unapologetically look for contamination, to break with the staggered national or linguistic loyalties that tormented Colombian writers until recently - is, perhaps, the great legacy of García Márquez … One Hundred Years of Solitude is a book that can be admired infinitely, but whose teachings are hardly applicable (the proof is what happens to its copycats). So I will repeat here what I have said elsewhere: no Colombian writer with a minimum of ambition would dare to follow through the paths already explored by the works of García Márquez; but no writer with a minimum of common sense would underestimate the possibilities that this work has opened for us.[11]

In 2007, Vásquez was included in Bogotá 39, a Hay Festival project that brought together the most notable Latin American writers under 39 years of age. That same year he began writing opinion pieces for El Espectador, the most prominent liberal Colombian newspaper. In his columns he was deeply critical of the governments of Álvaro Uribe in Colombia and Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. His political positions seem to defend freedom as a supreme value and an open, secular and liberal society:

For me it is still relevant for a novelist to participate in the social debate. For a philosopher too, for that matter; in any case, someone who thinks about reality in moral terms. Politicians do not usually do it, least of all in my country. The great contemporary debates in societies such as mine, about the legalization of drugs, about gay marriage, about abortion - politicians are never able to take them to the field of moral discussion, which is where they should be discussed. They discuss them in religious terms, they discuss them in political terms (in the most banal sense of the word). But they rarely try to understand these things from the point of view of individuals. Who are we hurting? Whose lives are we destroying or seriously affecting with a decision? This is not what they talk about.[12]

In 2008, Vásquez published a compilation of literary essays entitled The Art of Distortion (El arte de la distorsión in Spanish). That same year, he was invited to the Santa Maddalena Foundation, a retreat for writers located in Tuscany, Italy. There he began writing his novel The Sound of Things Falling.

Published in April 2011, The Sound of Things Falling was awarded the Alfaguara Prize and became one of the major Colombian novels of recent decades. The Colombian writer Héctor Abad Faciolince saluted it as “the best verbal creation I have read in all the Colombian literature of recent times”.[13] The novel provoked similar enthusiasm in translation. In Italy, it won the Premio Gregor von Rezzori-Città di Firenze; with the English translation, Vásquez became the first Latin American and the second Spanish-language author to win the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. The French translation was instrumental to Vásquez being awarded the Prix Roger Caillois; in the United States, the novel appeared on the cover of The New York Times Book Review, where Edmund White called it “A brilliant new novel...gripping...absorbing right to the end”. Lev Grossman, in Time magazine, wrote about Vásquez:

Vásquez is often compared to Roberto Bolaño, another Latin American writer in full flight from magical realism. […] Like Bolaño, he is a master stylist and a virtuoso of patient pacing and intricate structure, and he uses the novel for much the same purpose as Bolaño did: to map the deep, cascading damage done to our world by greed and violence and to concede that even love can't repair it.[14]

The return to Bogotá (2012)

editIn 2012, after sixteen years in Europe, Vásquez returned with his family to Colombia. The following year he was writer in residence at Stanford University, in California, United States. There he finished the short novel Reputations, the story of a political cartoonist. The book was published in April 2013 and went to win the Royal Spanish Academy Award and the Prémio Casa de América Latina de Lisboa, among others. After publication in the United States, The New York Review of Books called it Vásquez's "most intelligent and persuasive work":

With his book of Belgian short stories and his five Colombian novels, Vásquez has accumulated an impressive body of work, one of the most striking to have emerged in Latin America so far this century … Like Conrad’s best novels, Vásquez’s are tautly written—every line is charged with acute observation and analysis. In this he also recalls Borges, albeit in a more down-to-earth, nonmetaphysical mode.[15]

In August 2014, Vásquez left his weekly column in El Espectador, but continues to write occasional opinion pieces. He was frequently moved to write by the peace negotiations that the Colombian government was carrying out in Havana, Cuba, with the FARC guerrilla. In El País (Madrid) and The Guardian (London), he repeatedly defended the peace process and the need to put an end to the war that has ravaged his country during the last decades.[16][17][18] He has been one of the most vocal supporters of the peace agreements. In 2015, Vásquez published The Shape of the Ruins. It is his most challenging novel, as it mixes various genres to explore the consequences of two murders that have marked Colombian history: those of Rafael Uribe Uribe (1914) and Jorge Eliécer Gaitán (1948). The novel was very well received both in Colombia and abroad. Interviewed by Colombian magazine Arcadia, Vásquez said:

The Shape of the Ruins is by far the most difficult challenge that I have faced as a novelist. In part, this is due to everything the novel tries to do at the same time: it is an autobiography, a historical exploration, a criminal novel, a conspiracy theory, a meditation on what we are as a country ... I had to write 26 different versions to discover the one that best suited the book. Or rather: the one that was able to put everything together in the same plot[19].

With the novel, Vásquez became the first Latin American to win the Premio Casino da Póvoa, Portugal’s most prestigious award for fiction in translation. The novel was also shortlisted for the Premio Bienal de Novela Mario Vargas Llosa and for the Man Booker International Prize. In The New York Review of Books, Ariel Dorfman wrote:

Juan Gabriel Vásquez … has succeeded García Márquez as the literary grandmaster of Colombia, a country that can boast of many eminent authors … Readers might expect that Vásquez has written a noir detective novel that investigates a crime that has gone unpunished for seventy years and restores some semblance of justice. Nothing, however, is that orderly in The Shape of the Ruins, which subverts the crime genre, presenting the hunt for culprits within the frame of what seems to be a Sebaldian memoir.

In 2016 the Barcelona-based publisher Navona commissioned Vásquez to translate one of his favorite novels, Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. The same translation was published by Angosta Editores, a small Colombian press owned by the writer Héctor Abad Faciolince.

In February 2017, Vásquez was invited by the University of Bern to occupy the Friedrich Dürrenmatt chair. The result of these courses was a collection of essays around the art of the novel: Travels with a Blank Map (Viajes con un mapa en blanco in Spanish). The book was published in November of that same year.

In 2018, 17 years after Lovers on All Saint's Day, Vásquez published his second collection of short stories, Songs for the Flames (Canciones para el incendio in Spanish). It was scheduled for publication in the UK in 2020.

Recognition and awards

edit- 2009 - Shortlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize for The Informers

- 2007 - Premio Qwerty, (Spain) for The Secret History of Costaguana

- 2007 - Premio Fundación Libros & Letras (Colombia) for The Secret History of Costaguana

- 2007 - Premio Nacional de Periodismo Simón Bolívar (Colombia) for “The Art of Distortion” (essay)

- 2011 - Alfaguara Prize (Spain) for The Sound of Things Falling

- 2012 - Prix Roger Caillois (France)

- 2012 - Premio Nacional de Periodismo Simón Bolívar (Colombia) for "Una charla entre pájaros" (essay)

- 2013 - Gregor von Rezzori Award (Italy) for The Sound of Things Falling

- 2014 - International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award

- 2014 - Shortlisted for the Premio Bienal de Novela Mario Vargas Llosa (Perú) for Reputations

- 2014 - Premio Literario Arzobispo Juan de San Clemente, (Spain) for Reputations

- 2014 - Premio Real Academia Española (Spain) for Reputations

- 2016 - Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France)[citation needed]

- 2016 - Prémio Casa de América Latina de Lisboa (Portugal) for Reputations

- 2016 - Prix Carbet des Lycéens (Martinique) for Reputations

- 2016 - Shortlisted for the Premio Biblioteca de Narrativa Colombiana (Colombia) for The Shape of the Ruins

- 2016 - Shortlisted for the Premio Bienal de Novela Mario Vargas Llosa (Perú) for The Shape of the Ruins

- 2018 - Officer's Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (Spain)

- 2018 - Prémio Literário Casino da Póvoa (Portugal) for The Shape of the Ruins

- 2019 - Shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize for The Shape of the Ruins

- 2022 - Royal Society of Literature International Writer[20]

Works

editNovels

edit- 1997 - Persona

- 1999 - Alina suplicante

- 2004 - Los informantes (The Informers, 2008)

- 2007 - Historia secreta de Costaguana (The Secret History of Costaguana, 2010)

- 2011 - El ruido de las cosas al caer (The Sound of Things Falling, 2013)

- 2013 - Las reputaciones (Reputations, 2015)

- 2015 - La forma de las ruinas (The Shape of the Ruins, 2018)

- 2020 - Volver la vista atrás (Retrospective, 2022)

Short stories

edit- 2001 (Colombia; 2008, expanded version, Spain) - Los amantes de Todos los Santos (UK: The All Saints’ Day Lovers; US: Lovers on All Saints’ Day, 2016)

- 2018 - Canciones para el incendio

Essays

edit- 2004 - Joseph Conrad. El hombre de ninguna parte

- 2009 - El arte de la distorsión

- 2011 - La venganza como prototipo legal alrededor de la Ilíada

- 2017 - Viajes con un mapa en blanco

- 2023 - La traducción del mundo

Journalism

edit- 2022 - Los desacuerdos de paz

Poetry

edit- 2022 - Cuaderno de septiembre

References

edit- ^ Vervaeke, Jasper (March 1, 2018). "La obra y trayectoria tempranas de Juan Gabriel Vásquez". Pasavento. Revista de Estudios Hispánicos. 6 (1). Universidad de Alcala: 189–210. doi:10.37536/preh.2018.6.1.810. hdl:10067/1687420151162165141. ISSN 2255-4505.

- ^ Hans Ulrich Obrist. Conversations in Colombia. Bogotá: La oficina del doctor, 2015.

- ^ a b "Escribimos porque la realidad nos parece imperfecta: Entrevista con Jasper Vervaeke y Rita de Maeseneer". Ciberletras, 23 (2010).

- ^ "Gracias, señora Munro". El Espectador, October 17, 2013.

- ^ Miguel Silva. "Los amantes de Todos los Santos". Revista Gatopardo (June 2003).

- ^ Xavi Ayén. "El colombiano Vásquez publica relatos de tono centroeuropeo". La Vanguardia, May 15, 2002.

- ^ Jordi Carrión. "Invitació a la lectura". Avui, September 3, 2001.

- ^ Maya Jaggi. "A Life in Writing: Juan Gabriel Vásquez". The Guardian, June 25, 2010.

- ^ Larry Rohter. "In 1940s Colombia, Blacklists and 'Enemy Aliens'". The New York Times, August 2, 2009.

- ^ Jonathan Yardley. 'Jonathan Yardley reviews "The Informers" by Juan Gabriel Vásquez'. The Washington Post, August 2, 2009.

- ^ Juan Gabriel Vásquez. "La vieja pregunta". El Espectador, March 20, 2014.

- ^ "Creo en la novela como manera de dialogar con el mundo: Entrevista con Jasper Vervaeke". In Jasper Vervaeke, Juan Gabriel Vásquez: la distorsión deliberada. Antwerp: University of Antwerp, 2015.

- ^ Héctor Abad Faciolince. "La música del ruido". El Espectador, June 5, 2011.

- ^ Lev Grossman. "Dope Opera". Time, August 5, 2013.

- ^ David Gallagher. "Akin to Conrad in Colombia". The New York Review of Books, October 27, 2016.

- ^ Juan Gabriel Vásquez. "La paz sin mentiras". El País, August 18, 2016.

- ^ Juan Gabriel Vásquez. "Último alegato por la paz". El País, October 1, 2016.

- ^ Juan Gabriel Vásquez. "Peace has been reached in Colombia. Amid the Relief is Apprehension". The Guardian, August 26, 2016.

- ^ Juan David Correa. "Los hechos que marcaron nuestra historia son momentos de engaños". Arcadia, November 20, 2015.

- ^ "RSL International Writers". Royal Society of Literature. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

Sources

edit- Vervaeke, Jasper (2017). "Crónica de una consagración literaria. Juan Gabriel Vásquez y España". Resistencia de los negros en el virreinato de México (siglos XVI-XVII). pp. 149–165.

- Benmiloud, Karim (2017). Juan Gabriel Vásquez: Une archéologie du passé colombien récent. Presses universitaires de Rennes. pp. 9–34.

Further reading

edit- Juan Gabriel Vásquez: la distorsión deliberada (2023), monograph by Jasper Vervaeke, Verbum