You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (October 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

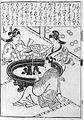

The hibachi (Japanese: 火鉢, fire bowl) is a traditional Japanese heating device. It is a brazier which is a round, cylindrical, or box-shaped, open-topped container, made from or lined with a heatproof material and designed to hold burning charcoal. It is believed hibachi date back to the Heian period (794 to 1185).[1] It is filled with incombustible ash, and charcoal sits in the center of the ash.[2] To handle the charcoal, a pair of metal chopsticks called hibashi (火箸, fire chopsticks) is used, in a way similar to Western fire irons or tongs.[3] Hibachi were used for heating, not for cooking.[3] It heats by radiation,[4] and is too weak to warm a whole room.[2] Sometimes, people placed a tetsubin (鉄瓶, iron kettle) over the hibachi to boil water for tea.[3] Later, by the 1900s, some cooking was also done over the hibachi.[5]: 251

Traditional Japanese houses were well ventilated (or poorly sealed), so carbon monoxide poisoning or suffocation from carbon dioxide from burning charcoal were of lesser concern.[2] Nevertheless, such risks do exist, and proper handling is necessary to avoid accidents.[5]: 255 [6] Hibachi must never be used in airtight rooms such as those in Western buildings.[6]: 129

In North America, the term hibachi refers to a small cooking stove heated by charcoal (called a shichirin in Japanese),[1] or to an iron hot plate (called a teppan in Japanese) used in teppanyaki restaurants.[1]

-

A traditional charcoal hibachi, made c. 1880–1900

-

House of the Edo period (Fukagawa Edo Museum)

-

Two women and a man warming themselves by a hibachi

See also

edit- Brazier

- Japanese traditional heating devices:

- Kamado: a kitchen stove

- Shichirin: a portable brazier

- Tabako-bon: a mini brazier to light tobacco in kiseru pipes

- Kotatsu: a covered table over a brazier

- Japanese tea utensils § Tea hearths

- Japanese cuisine

References

edit- ^ a b c "'Hibachi' Probably Doesn't Mean What You Think It Does". Japanese Food Guide. 5 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Dresser, Christopher (1882). Japan: Its architecture, art, and art manufactures. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 22–23. hdl:2027/yale.39002009493082.

- ^ a b c Hough, Walter (1928). "Collection of heating and lighting utensils in the United States National Museum". Bulletin of the United States National Museum. 141. Washington D.C.: United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution: 83–84. hdl:2027/uiug.30112032539204.

- ^ Tsujimoto, Kennosuke (1935). 煖房並に台所用熱源と一酸化炭素の害毒と其の對策(其一) [Heat sources for heating and kitchen, hazards of carbon monoxide and their prevention]. Kaji to eisei (家事と衛生) (in Japanese). 11 (1): 27. doi:10.11468/seikatsueisei1925.11.25. ISSN 1883-6615. (bibliographic data:[1])

- ^ a b Arnold, Edwin (1904). "The Japanese Hearth". In Singleton, Esther (ed.). Japan as seen and described by famous writers. New York: Dodd, Mead and company. pp. 250–256. hdl:2027/hvd.32044013638895.

- ^ a b 大阪市立衛生試験所(Osaka City sanitary laboratories) (1940). 炭火中毒の話 – 一酸化炭素中毒. Kaji to eisei (家事と衛生) (in Japanese). 16 (2): 126–128. doi:10.11468/seikatsueisei1925.16.2_123. ISSN 1883-6615. (bibliographic data:[2])