Hamiota australis, the southern sandshell, is a species of freshwater mussel, an aquatic bivalve mollusc in the family Unionidae, the river mussels.

| Hamiota australis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Unionida |

| Family: | Unionidae |

| Genus: | Hamiota |

| Species: | H. australis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hamiota australis (Simpson, 1900)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Lampsilis australis Simpson, 1900 | |

This species is endemic to the United States.

Geography

editThe species occurs in the U.S. states of Alabama and Florida, in the Choctawhatchee, Yellow, and Escambia river basins.[4]

Taxonomy

editIt was first described by C. T. Simpson in 1900 as Lampsilis australis. Historically, it has sometimes been placed in Villosa.[4] In 2005, Roe and Hartfield placed it in a new genus Hamiota. Placement in the genus was based on characteristics such as a superconglutinate lure, placement and shape of the marsupia (gills), and release of larvae through the excurrent siphon.[5]

Ptychobranchus jonesi, the southern kidneyshell, has at times been mistakenly considered synonymous with this species, as they have a similar outer appearance and occur in the same river basins. However, H. australis occurs in smaller streams than P. jonesi.[1]

The specific name Hamiota australis, meaning "southern angler", comes from the Greek hamus, "to hook", and Latin australis, "southern".

Description

editThe southern sandshell is a medium-sized freshwater mussel with an elliptical shape. Adults are about 70-80 mm (2.7 - 3 in.) in length. The shell is greenish in color when they are young, while adults are dark greenish-brown to black. The shell is smooth and shiny, and usually without rays. The nacre is white or bluish-white.[4][6]

Females are slightly more inflated on the posterior ventral (top right) edge.

Habitat

editIt is found in small creeks and rivers with stable river bottoms consisting of sand or gravel, in areas with woody debris or logs.[4][7] It prefers deeper and faster-flowing areas of the river rather than shallow banks.[8]

The species requires clear water for feeding and reproduction. Increased suspended sediment causes mussels to close their valves and reduce feeding. It can also interfere with the species' ability to attract a host fish if the fish cannot see its lure in muddy water.[4]

Life Cycle

editIt is mainly sedentary, and likely feeds on zooplankton and organic detritus by siphoning the water like other species of Unionidae.

Eggs are fertilized inside the shell after the female takes in sperm released by the male into the current. Fertilization occurs in late summer, the female holds the eggs over winter as they develop, and releases approximately 1700 larvae in the spring. The eggs move to the female's gills where they mature into larvae called glochidia. The larvae have a parasitic stage during which they must attach to the gills, fins, or skin of a fish to transform into a juvenile mussel.[4] The host fish for Hamiota australis has not been studied, but is thought to be Micropterus (black bass) species, similar to other mussels in the same genus.[8]

The southern sandshell uses mimicry in the form of a superconglutinate lure to attract a host fish, a feature unique to Hamiota species. This is a mass of all the year's larvae encased in a mucous package that resembles a small fish. The larvae mass is dangled in the current, attached to both the female's gills by a mucous tether around 10-60cm long, with the intention of attracting a host fish. When the fish bites the lure, the larvae disperse and attach to the fish's gills or skin. The host fish's immune system forms a cyst around the glochidia, and they feed off the fish's tissues. Once the glochidia have developed into juvenile mussels (around 2-4 weeks for most mussel species), they drop off and bury themselves in the stream bed.[4][1][9][5]

In addition to the superconglutinate lure, it can also utilize a mantle lure, which involves flapping the edge of its body to attract a fish, though it is smaller than in Lampsilis species. This is thought to be an adaptation to low currents.[10]

Conservation

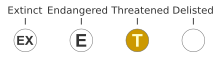

editThe southern sandshell was listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act in 2012.[4] It has been extirpated from approximately 31%-41% of its historical range. Out of 51 historical sites, it has recently been found in 30, with 5 sites uncertain.[1]

The biggest threat to this species is the modification and destruction of river habitats, with sedimentation a leading factor. Sedimentation, caused by erosion from agriculture, cattle grazing, gravel mining, and housing and road development, is a major problem in the Choctawhatchee River watershed and causes shallower waters which are less suitable habitat for this species.[8] Unpaved road crossings are a cause of sedimentation in the Yellow River. The suspended silt also affects feeding, reproductive habits, and can cause suffocation of aquatic species.

Land surface run-off additionally allows pollutants such as nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers, sewage, and manure to enter the rivers, causing algae overgrowth and lowering dissolved oxygen. Freshwater mussels are also extremely sensitive to contaminants such as chlorine, metals, ammonia, and pesticides.[11]

Dams cause significant impact to river habitats downstream. In its listing determination, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service noted that "dams eliminate or reduce river flow within impounded areas, trap silts and cause sediment deposition, alter water temperature and dissolved oxygen levels, change downstream water flow and quality, affect normal flood patterns, and block upstream and downstream movement of mussels and their host fishes." Effects of these changes on mussel populations have been documented.

Extreme weather such as floods and droughts are potential threats to the species, as are invasive species such as the Asian clam and flathead catfish. Loss of genetic diversity due to fragmented populations is likely but has not been studied.[4]

The species is listed as G2 Imperiled by NatureServe and Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List.[1][12]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Jackson, D. R.; Cordeiro, J. "Hamiota australis". NatureServe Explorer. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Southern Sandshell (Hamiota australis)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ 63 FR 12664

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Determination of Endangered Species Status for the Alabama Pearlshell, Round Ebonyshell, Southern Kidneyshell, and Choctaw Bean, and Threatened Species Status for the Tapered Pigtoe, Narrow Pigtoe, Southern Sandshell, and Fuzzy Pigtoe, and Designation of Critical Habitat: Final rule". UWFWS Environmental Conservation Online System. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ a b Roe, Kevin J.; Hartfield, Paul D. (2005). "Hamiota, a new genus of freshwater mussel (Bivalvia: Unionidae) from the Gulf of Mexico drainages of the southeastern United States". The Nautilus. 119.

- ^ Ralph Edward Mirarchi, Ericha Shelton-Nix (2017). Alabama Wildlife, Volume 5. University of Alabama Press. p. 75. ISBN 9780817319618.

- ^ Niraula, Bijay B. (2015). "Instream Habitat Associations Among Three Federally Threatened and a Common Freshwater Mussel Species in a Southeastern Watershed". Southeastern Naturalist. 14 (2): 221–230. doi:10.1656/058.014.0205.

- ^ a b c Niraula, Bijay B. (2015). "Microhabitat Associations among Three Federally Threatened and a Common Freshwater Mussel Species". American Malacological Bulletin. 33 (2): 195–203. doi:10.4003/006.033.0201.

- ^ Haag, Wendell (1995). "An extraordinary reproductive strategy in freshwater bivalves: prey mimicry to facilitate larval dispersal". Freshwater Biology. 34 (3): 471-476. Bibcode:1995FrBio..34..471H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.1995.tb00904.x.

- ^ Wendall, R. Haag (2008). "Adaptations to Host Infection and Larval Parasitism in Unionoida". Journal of the North American Benthological Society. 27 (2): 370–394. doi:10.1899/07-093.1.

- ^ Daniel L. Hernandez (2016). "Nitrogen Pollution Is Linked to US Listed Species Declines". BioScience. 66 (3): 213–222. doi:10.1093/biosci/biw003.

- ^ Cummings, K.; Cordeiro, J. (2012). "Hamiota australis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T189213A8702226. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T189213A8702226.en. Retrieved 15 August 2024.