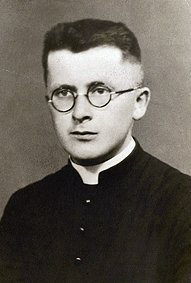

Francesco Giovanni Bonifacio (7 September 1912 – 11 September 1946) was an Italian Catholic priest, killed by the Yugoslav communists in Grisignana (then Italy now Croatia); he was beatified in Trieste on 4 October 2008.

Early life

editFrancesco (Checco) Bonifacio was born on 7 September 1912 in Pirano,[1] Istria which was then part of Austria Hungary, later Italy, and is now part of Slovenia. He was the second of seven children born to Giovanni and Luigia Busdon Bonifacio. His father was a stoker on steamers sailing out of Trieste, which kept him away much of the time. His mother took a job as a cleaning lady to supplement their income. The family were devout Catholics. Francesco attended the local elementary school of Pirano and received religious education at the local parish of San Francesco where he served as an altar boy.

Seminarian

editIn 1924, Bonifacio entered the seminary in Capodistria-Koper,[1] where he earned the nickname of El Santin (the little Saint) for his obedience, meekness, service, and availability to his companions. On Christmas Eve 1931, his father died. The following year he entered the Central Theological Seminary of Gorizia. These were turbulent years for Italy: Fascism had already consolidated its political power and sought to reduce the influence of the Catholic Church in Italy. In 1934, a press campaign was mounted by the fascists against the local Church because of a speech by Bishop Luigi Fogar. However, young Bonifacio was not particularly interested in politics.

Priesthood

editOn 26 October 1936, Bonifacio was ordained as a deacon in Trieste by Archbishop Carlo Margotti of Gorizia and on 27 December 1936, he was ordained a priest in the Trieste Cathedral of San Giusto. He celebrated his first service in his native Pirano church San Giorgio Dom on 3 January 1937. A few months later he was assigned as vicar at Cittanova d'Istria,[1] where he created the local section of the Azione Cattolica (Catholic Action).

On 13 July 1939, Bishop of Trieste Antonio Santin appointed Bonifacio curate of Villa Gardossi or Crassizza (now Krasica), a small borough located in the Buiese between Buie and Grisignana. The community was made up of a few small villages, (Baredine, Punta, Lozzari, Buzzai, Gardossi, Monte Cini, Musolini, Stazia Loy, Costellaz, Braichi and Radani), and had a population of 1300 people, most of them peasants. His mother and younger brother join him there. The rectory had neither running water nor electricity; food was meagre and consisted mainly of soup, polenta, and eggs.[2]

He quickly organized the Azione Cattolica movement and a choir in the parish. He taught religion at the local school and began a small library. Don Francesco shared what little food he had with the poorest of his parishioners. Not of robust health, he suffered from asthma, a persistent cough and chronic bronchial and lung problems. Nonetheless, his afternoons were devoted to parish visits. In all types of weather, he travelled the length and breadth of the valley, on foot or by bicycle, dispensing comfort and encouragement. Don Francesco was well-liked by the people.[2]

World War II

editWar broke out in June 1940, but had very little effect in Istria until the Italian debacle of 8 September 1943. Components of the Italian and Yugoslav Communist Parties organized to seize control. The Villa Gardossi area with its forests and isolated houses, was an ideal location for the Partisan guerrillas. German troops arrived around mid-September occupying the key positions of Istria. Don Francesco continued his routine of service to his community, but faced this new situation with great energy and extreme courage. During a German Army cordon and Army search operation, he risked his life to recover and bury the bodies of fallen partisans. He prevented the Germans from setting a house on fire because they believed it to be used to shelter partisans. He prevented a protest at the Fascist Headquarters in Buie after the murder of a peasant, and saved from a Partisan firing squad a man they believed to be a German informer. Youths who didn't want to be drafted into the new Italian Fascist Army or forced to join the Partisan forces found refuge at the rectory.[3]

After the war

editIn May 1945 German and Italian forces were driven out of Istria by the Partisan Army. The region was almost entirely annexed to Tito's new Communist Yugoslavia. The new regime saw the Catholic Church as a potential enemy. New holidays were introduced to replace religious feast days. The new government discouraged people from attending Church, and positioned agents outside churches to note the names of those who did. Don Francesco was seen as a leader in the community and a threat to the new regime. He was informed by some loyal parishioners that some members of his congregation had embraced the new standards, and he was warned not to trust them. At this time Yugoslav communism was modelled on the Soviet style, and along with the usual violence, they were also trained in the use of misinformation, propaganda and false accusations. He travelled to Trieste to consult with his bishop who advised him to be cautious and to limit his activities to within the church, avoiding any public stance.[2] Monsignor Santin also urged him to remain "true to [his] duties without being intimidated by anyone".[3] Don Francesco was accused of being a “Subversive and an anti-communist”. He answered these false accusations by holding Action's meeting in the Church, with the doors wide open, so that everyone could observe what was said.

Death

editA few days before his death, Don Francesco had been warned by some loyal parishioners that his life was in danger. He confided to fellow priest, Don Guido Bertuzzo, the Sicciole's Chaplain, that even talking on the streets had become very dangerous for him since he was under strict surveillance. He recommended to an activist parishioner that he "mark his arms" since he knew that the "Druses" (communists) were now cutting off the heads of their victims.

Father Bonifacio was likely killed on 11 September 1946, the same day he disappeared and his body was never recovered.[4] He was seen alive for the last time around 4 p.m. by Don Giuseppe Rocco, his confessor and the Chaplain of Peroi. A later reconstruction indicated that he was stopped on his way back from Grožnjan by some "Popular Guards", beaten to death, and his body thrown into a foiba.[5] Other unconfirmed versions stated that he was also reputedly physically abused, stoned, and eventually stabbed twice. When his brother went to ask for information from the local "Popular Militia" (Communist Police) he was arrested on accusation of spreading false and anticommunist propaganda. Shortly afterwards the family moved to Italy.

The fate of Father (Don) Francesco Bonifacio was not the only violence committed against the Catholic Church of the former Italian territories ceded to Yugoslavia in 1945. In June 1946, Trieste bishop Mons. Santin was stopped and beaten by communist activists while going to Koper/Capodistria, then part of his diocese, attending the Ceremony of Confirmation; his delegate Mons Giacomo Ukmar was also beaten on 23 August 1947, the same day as another priest Don Miro Bulesic was murdered; his throat was slit.[5] On 11 November 1951, another Trieste bishop delegate Mons. Giorgio Bruni, was beaten when attending Confirmations in Carcaseon on the bishop's behalf.[3]

Beatification

editThe then Bishop of Trieste Antonio Santin, born in Rovigno now Rovinj in Croatia, first submitted the proposal for the beatification of Don Francesco Bonifacio back in 1957. Mons. Eugenio Ravignani, current bishop of Trieste, wrote a report on the priest's murder on 3 July 1983. He wrote that Don Francesco Bonifacio was murdered at the age of 34 on the evening of 11 September 1946. For many years nothing was known until witnesses confirmed and shed light on what happened that night. All of the testimonies said that Bonifacio was beaten and thrown into a pit. Other accounts mention him being stoned, injured with a knife and shot.[6]

Controversy

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) |

The 7 February 2006 issue of Avvenire carried an article which stated that Don Luigi Rocco, who received a visit from Don Bonifacio in 1946 in Groznjan, said that the priest was thrown into the pit Martinesi in Groznjan.[7] While Bonifacio's body may have been thrown into the foiba called Martines, this is uncertain because his remains were never found. It is also possible that his body was burned.[8]

The peace treaty of Paris signed in 1947, when Istria was almost entirely ceded to Yugoslavia, is still an issue that marks the relations between Italy and the new states of the former Federation of Yugoslavia. The Foibe atrocities are a divisive subject in contemporary Italian politics. Right-wing media accuse the left of attempting to downplay the massacres while focusing attention on crimes committed by the Fascists.[6] Bonifacio and his martyrdom at the hands of Communists, has become an important symbol of the story of the Foibe and the exodus of Italians from Istria.

Famous Istrian priest Mons. Bozo Milanovic, the author of many books on Istrian history and crimes committed against priests, wrote a book “Istra u dvadesetom stoljecu” (“Istria in the twentieth century”, Pazin 1996). In this book, he described the work of the “college of priests St. Pavao for Istria”, 1946. He wrote that they discussed a “secretly missing Italian minister in Bujstina (…)” while Ivan Grah, minister in the Istrian villages of Sisan and Liznjan, in his book “Istarska crkva u ratnom vrihoru” (1943–1945) (Istrian Church in war winds), published in Pazin in 1992, described the crimes against Istrian priests but never mentioned Don Bonifacio. However, in the feuilleton Istarski Svecenici - Ratne i Poratne Zrtve (Istrian priests–war and post-war victims), published in the monthly “Ladonja” in August 2005, Ivan Grah wrote about Francesco Bonifacio. From 1939 till his suffered death, he was the head of the parish of Krasica in Bujstina. After the end of the war, the Yugo-Communist authorities could not bear him because he interfered too much with their ideological work. On 10 September 1946, came the news that in Bujstina they–the communists- had a list of younger priests who had to be “liquidated” by the Popular Guard. Don Bonifacio was first on the list, but he decided to carry on with his duties as a priest. The following day, 11 September, in the evening, the Popular Guard was waiting for him as he returned home on foot from Groznjan and, after a crabbed discussion, he was coercively taken away. Since then, all traces of him have disappeared and the place of his death remains unknown (...)”. The Communist writer, publicist and journalist Giacomo Scotti, an Italian Communist expatriate from Naples, in his book “Cry from the foiba” (Rijeka 2008) does not mention the murder of Don Bonifacio or his body being thrown into a foiba. Giacomo Scotti a great expert on this topic in Croatia and Italy wrote: “As soon as I started writing about the beatification of Don Bonifacio being held in Trieste and about the murder, I stated that this priest is not present on the list of foibe victims. The League of Anti-fascist Fighters told me that Don Bonifacio went missing in September 1946, and that there is no information on his murder or on his death in a pit.

The beatification ceremony was held in the Trieste Cathedral of Saint Giusto on 4 October 2008 by Trieste Bishop Eugenio Ravignani; Archbishop Angelo Amato represented the Pontiff.

In 2005 a Trieste square was named after Francesco Bonifacio. Piazza Francesco Bonifacio is a park in Metropolitan Naples.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "Beato Francesco Bonifacio, sacerdote e martire", Diocesi di Trieste

- ^ a b c Pettiti, Gianpiero. "Beato Francesco Giovanni Bonifacio", Santi e beati, December 30, 2008

- ^ a b c ""Don Francesco Bonafacio", Parish of San Gerolamo, Trieste". Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Testa, Merko. "Don Francesco Bonifacio", Zenit, July 8, 2008

- ^ a b "The Beatification of Don Bonifacio", Associazione Nazionale Venezia Giulia e DAlmazia, November 2008

- ^ a b "Beatification set for 'Foibe' priest", Italy Magazine, August 20, 2008

- ^ "Don Francesco Bonifacio", Avvenire, February 7, 2006

- ^ Vigna, Marco. "The Priests Murdered in the Foibe Massacres", “Comune di Pignataro, February 9, 2016

Sources

edit- Raccolta di articoli su Francesco Bonifacio:

- M.R. Eugenio Ravignani, Bishop of Trieste.

- Biography di don Francesco Bonifacio

- Don Francesco Bonifacio beatification in Trieste

- Interview to Giovanni Bonifacio

- Interview to mons. Rocco su don Bonifacio

- Interview to mons. Malnati su don Bonifacio

- Don Bonifacio and the Catholic Action Movement.(C78.NBR)

- 1. ^ Quotidiano Avvenire del 5 agosto 2008: "Trieste, beato il 4 ottobre il prete martire della foiba."