Ferdinand Hurter (15 March 1844 – 12 March 1898) was a Swiss industrial chemist who settled in England. He also carried out research into photography.

Ferdinand Hurter | |

|---|---|

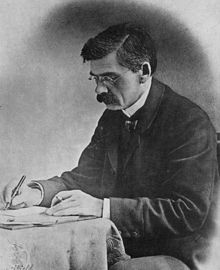

Ferdinand Hurter. Photograph taken by his colleague in photographic research, Vero Charles Driffield | |

| Born | 15 March 1844 |

| Died | 12 March 1898 (aged 53) |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Alma mater | Zürich Polytechnic, Heidelberg University |

| Known for | chemistry, photographic research |

| Awards | Progress Medal of the Royal Photographic Society, 1898 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemist |

| Institutions | Gaskell, Deacon & Co., United Alkali Company |

| Doctoral advisor | Robert Bunsen, Gustav Kirchhoff |

Early life

editFerdinand Hurter was born in Schaffhausen, Switzerland, the only son of Tobias Hurter, a bookbinder, and his wife Anna Oechslein.[1] His father died when Ferdinand was aged only two and his mother worked as a nurse to support him and his sister Elizabeth. She later married her late husband's half-brother, David, and Ferdinand developed a strong relationship with his stepfather.[2] After education at the local Gymnasium he became an apprentice to a dyer in Winterthur before moving to Zürich to work in a silk firm. He then attended Zürich Polytechnic before going to Heidelberg University. Here he studied chemistry under Robert Bunsen and physics under Gustav Kirchhoff. He graduated Ph.D. with the highest honours in 1866.[3]

Career

editHurter was offered a professorship in Aarau but declined this and, with a few letters of introduction, arrived in Manchester in 1867.[4] He joined Henry Deacon and Holbrook Gaskell at their alkali manufacturing business, Gaskell, Deacon & Co., in Widnes, Lancashire.[5] Here he became chief chemist and worked with Deacon to develop a process to convert hydrochloric acid, a waste by-product of the Leblanc process of making alkali, to chlorine which was then used to manufacture bleaching powder.[1][6] He was a pioneer in applying the principles of physical chemistry and thermodynamics to industrial processes and by 1880 was considered to be a world authority on the manufacture of alkali.[1][7] He was a strong defender of the Leblanc process against the other methods of manufacturing alkali being developed at the time[8] although he did research the ammonia-soda process but without any success.[9] He argued against the production of alkali by the electrolysis of brine because of the enormous amount of electrical power this would require[10] although he was later to have second thoughts.[11]

When the Leblanc factories merged in 1890 to form the United Alkali Company, Hurter was placed in charge of developing a research laboratory in Widnes. This was later named after him.[12] He played a part in the foundation of the Society of Chemical Industry in 1881, becoming its chairman in 1888–1890.[13] He published 24 papers in English journals alone.[14] He gave many lectures to try to popularise scientific subjects.[15] As chief chemist to the United Alkali Company, despite his failing health, he travelled to a number of countries in Europe and also made one visit to the USA.[16] The Society of Chemical Industry endowed the Hurter Memorial Lecture in his name.[13]

Personal

editIn 1871 Hurter married Hannah Garnett of Farnworth, Widnes, with whom he had six children, one of whom died in infancy. They lived first at Prospect House in Crow Wood and later in Wilmere House, Widnes.[7] Hurter remained a Swiss citizen throughout his life and sent his children to receive part of their education in Switzerland.[17] He enjoyed music and played the clarinet and piano. He also took an interest in photography, collaborating in research with Vero Charles Driffield, an engineer at the Gaskell-Deacon works. Together they published many papers (in addition to Hurter's papers in chemistry). They were jointly awarded the Progress Medal of the Royal Photographic Society in 1898.[18][19] The results of their research revolutionised photography.[13] Hurter campaigned for free education and for the introduction of the metric system into Britain. He died at his home in Cressington Park, Liverpool and was buried in the churchyard of Farnworth church. His estate was valued at slightly less than £6,300.[1]

See also

edit- Hurter and Driffield

- H&D speed numbers for film speed measurements

References

editCitations

- ^ a b c d N. J. Travis (2004) ‘Hurter, Ferdinand (1844–1898)’, rev., Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, [1] Retrieved on 10 July 2007

- ^ Hardie 1950, p. 165.

- ^ Hardie 1950, p. 166.

- ^ Hardie 1950, p. 167.

- ^ Hardie 1950, p. 67.

- ^ Hardie 1950, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Hardie 1950, p. 168.

- ^ Hardie 1950, p. 164.

- ^ Hardie 1950, p. 169.

- ^ Hardie 1950, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Hardie 1950, p. 190.

- ^ Hardie 1950, pp. 175–176.

- ^ a b c Hurter Memorial Lecture, Society of Chemical Industry, archived from the original on 27 September 2007, retrieved 10 July 2007

- ^ Hardie 1950, p. 170.

- ^ Hardie 1950, p. 171.

- ^ Hardie 1950, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Hardie 1950, p. 172.

- ^ Hardie 1950, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Royal Photographic Society. Progress medal. Web-page listing people, who have received this award since 1878 ("Progress Medal - the Royal Photographic Society". Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.): “Instituted in 1878, this medal is awarded in recognition of any invention, research, publication or other contribution which has resulted in an important advance in the scientific or technological development of photography or imaging in the widest sense. This award also carries with it an Honorary Fellowship of The Society. […] 1898 Ferdinand Hurter and Vero C Driffield […]”

Sources

- Hardie, David William Ferguson (1950), A History of the Chemical Industry of Widnes, London: Imperial Chemical Industries Limited, General Chemicals Division, OCLC 7503517