Enlil and Ninlil, the Myth of Enlil and Ninlil, or Enlil and Ninlil: The begetting of Nanna is a Sumerian creation myth, written on clay tablets in the mid to late 3rd millennium BC.

Compilation

editThe first lines of the myth were discovered on the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, catalogue of the Babylonian section (CBS), tablet number 9205 from their excavations at the temple library at Nippur. This was translated by George Aaron Barton in 1918 and first published as "Sumerian religious texts" in "Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions", number seven, entitled "A Myth of Enlil and Ninlil".[1] The tablet is 6.5 inches (17 cm) by 4.5 inches (11 cm) by 1.2 inches (3.0 cm) at its thickest point. Barton noted that Theophilus G. Pinches had published part of an equivalent Akkadian version of the same story in 1911, noting "The two texts in general agree closely, though there are minor variations here and there."[2]

Another tablet from the same collection, number 13853 was used by Edward Chiera to restore part of the second column of Barton's tablet in "Sumerian Epics and Myths", number 77.[3] Samuel Noah Kramer included CBS tablets 8176, 8315, 10309, 10322, 10412, 13853, 29.13.574 and 29.15.611. He also included translations from tablets in the Nippur collection of the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul, catalogue number 2707.[4][5] Another tablet used as cuneiform source for the myth is held by the British Museum, BM 38600, details of which were published in 1919.[6] Other tablets and versions were used to bring the myth to its present form with the latest composite text by Miguel Civil produced in 1989 with latest translations by Willem Römer in 1993 and Joachim Krecher in 1996.[7]

Story

editThe story opens with a description of the city of Nippur, its walls, river, canals and well, portrayed as the home of the gods and, according to Kramer "that seems to be conceived as having existed before the creation of man." A.R. George suggests "According to a well-known tradition, represented by the myth of Enlil and Ninlil, time was when Nippur was a city inhabited by gods not men, and this would suggest that it had existed from the very beginning." He discusses Nippur as the "first city" (uru-sag, 'city-head(top)') of Sumer.[8] This conception of Nippur is echoed by Joan Goodnick Westenholz, describing the setting as "civitas dei", existing before the "axis mundi".[9]

"There was a city, there was a city -- the one we live in. Nibru (Nippur) was the city, the one we live in. Dur-jicnimbar was the city, the one we live in. Id-sala is its holy river, Kar-jectina is its quay. Kar-asar is its quay where boats make fast. Pu-lal is its freshwater well. Id-nunbir-tum is its branching canal, and if one measures from there, its cultivated land is 50 sar each way. Enlil was one of its young men, and Ninlil was one its young women."[10]

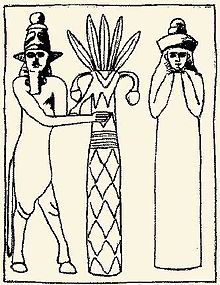

The story continues by introducing the goddess Nun-bar-ce-gunu warning her daughter Ninlil about the likelihood of romantic advances from Enlil if she strays too near the river. Ninlil resists Enlil's first approach after which he entreats his minister Nuska to take him across the river, on the other side the couple meet and float downstream, either bathing or in a boat, then lie on the bank together, kiss, and conceive Suen-Acimbabbar, the moon god. The story then cuts to Enlil walking in the Ekur, where the other gods arrest him for his relationship with Ninlil and exile him from the city for being ritually impure.

"Enlil was walking in the Ki-ur. As Enlil was going about in the Ki-ur, the fifty great gods and the seven gods who decide destinies had Enlil arrested in the Ki-ur. Enlil, ritually impure, leave the city! Nunamnir, ritually impure, leave the city! Enlil, in accordance with what had been decided, Nunamnir, in accordance with what had been decided, Enlil went. Ninlil followed."[10]

There follows three similar episodes as Enlil leaves the city, speaking to as the keeper of the city gate ("keeper of the holy barrier" or "man of the pure lock"), the man who guards Id-kura – the Sumerian river of the underworld (similar to the river Styx in Greek Mythology) – and lastly SI.LU.IGI, the underworld ferryman (similar to Charon). Each time Enlil tells these characters "When your lady Ninlil comes, if she asks after me, don't you tell her where I am!". Ninlil follows him asking each "When did your lord Enlil go by?" To this, Enlil (in disguise) tells her "My lord has not talked with me at all, O loveliest one. Enlil has not talked with me at all, O loveliest one" upon which Ninlil offers to have sex with him and each time they conceive another god. Two of the offspring are gods of the underworld, Nergal-Meclamta-ea and Ninazu. The third god, Enbilulu is called the "inspector of canals", however Jeremy Black has linked this god to management of irrigation.[11] The myth ends with praise for the fertility of Enlil and Ninlil.

"You are lord! You are king! Enlil, you are lord! You are king! Nunamnir, you are lord! You are king! You are supreme lord, you are powerful lord! Lord who makes flax grow, lord who makes barley grow, you are lord of heaven, lord plenty, lord of the earth! You are lord of the earth, lord plenty, lord of heaven! Enlil in heaven, Enlil is king! Lord whose pronouncements cannot be altered at all! His primordial utterances will not be changed! For the praise spoken for Ninlil the mother, praise be to the Great Mountain, Father Enlil!"[10]

Discussion

editJeremy Black discusses the problems of serial pregnancy and multiple births along with the complex psychology of the myth. He also notes that there are no moral overtones about Enlil being ritually impure.[11] Ewa Wasilewska noted about the location of the tale that "Black and Green suggest the Sumerians located their underworld in the east mountains where the entrance to Kur was believed to exist. He (Enlil) was thus the 'King of the Foreign Lands/Mountains,' where the underworld to which he was banished and from which he returned, was located."[12] Robert Payne has suggested that the initial scene of the courtship takes place on the bank of a canal instead of a river.[13]

Herman Behrens has suggested a ritual context for the myth where dramatic passages were acted out on a voyage between the Ekur and the sanctuary in Nippur.[14] Jerrold Cooper has argued for a more sociological interpretation, explaining about the creation of gods who seem to perform as substitutes for Enlil, he suggests the purpose of the work is "to tell the origins of four gods" and that it "explains why one (Suen) is shining in the heavens, while the other three dwell in the Netherworld". Cooper also argues that the text uses local geographical placenames in regard to the netherworld.[15]

From the analysis of Thorkild Jacobsen, Dale Launderville has suggested the myth provides evidence that Sumerian society prohibited premarital sex in a discussion entitled "Channeling the Sex Drive Toward the Creation of Community". He discusses the attributes of the gods "(1) the moon god was regarded as rejuvenating living things; (2) Nergal was associated occasionally with agricultural growth but more often with plague, pestilence, famine and sudden death; (3) Ninazu and (4) Enbilulu were forces that ensured successful agriculture." He concludes that the narrative exonerates Enlil and Ninlil indicating nature to have its way even where societal conventions try to contain sexual desire.[16]

Further reading

edit- Behrens, Hermann. 1978. Enlil und Ninlil. Ein sumerischer Mythos aus Nippur. Studia Pohl Series Major 8. Rome: Biblical Institute Press.

- Bottéro, Jean and Kramer, Samuel Noah. 1989, reprinted 1993. Lorsque les dieux faisaient l'homme rev. Éditions Gallimard. p. 105-115.

- Cooper, Jerrold S. 1980. "Critical Review. Hermann Behrens, Enlil und Ninlil etc.". In Journal of Cuneiform Studies 32. 175–188.

- Geller, M.J. 1980. "Review of Behrens 1978". In Archiv für Orientforschung 27. 168–170.

- Green, Margaret Whitney. 1982. "Review of Behrens 1978". In Bibliotheca Orientalis 39. 339–344.

- Hall, Mark Glenn. 1985. A Study of the Sumerian Moon-God, Nanna/Suen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. p. 524-526.

- Heimerdinger, Jane W. 1979. Sumerian literary fragments from Nippur. Occasional Publications of the Babylonian Fund 4. Philadelphia: The University Museum. 1, 37.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild. 1987. The Harps that Once .. Sumerian Poetry in Translation. New Haven/London: Yale University Press. p. 167-180.

- Röllig, Wolfgang. 1981. "Review of Behrens 1978". In Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 131. 430.

- Römer, Willem H.Ph. 1993a. "Mythen und Epen in sumerischer Sprache". In Mythen und Epen I. Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testaments III, 3. Kaiser, Otto (ed). Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus Gerd Mohn. p. 421-434.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ George Aaron Barton (1918). Miscellaneous Babylonian inscriptions, p. 52. Yale University Press. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Society of Biblical Archæology (London, England) (1911). Theophilus G. Pinches in Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology, Volume 33 f. 85. The Society.

- ^ Edward Chiera (1964). Sumerian epics and myths, 77, p. 5. The University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Samuel Noah Kramer (1944). Sumerian literary texts from Nippur: in the Museum of the Ancient Orient at Istanbul. American Schools of Oriental Research. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Samuel Noah Kramer (1961). Sumerian mythology: a study of spiritual and literary achievement in the third millennium B.C. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-60506-049-1. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1919). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, f. 190. Cambridge University Press for the Royal Asiatic Society.

- ^ Enlil and Ninlil - Electronic and Print Sources - The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998-.

- ^ A. R. George (1992). Babylonian topographical texts. Peeters Publishers. pp. 442–. ISBN 978-90-6831-410-6. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Miguel Ángel Borrás; Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (2000). Joan Goodnick Westenholz, The Foundation Myths of Mesopotamian Cities, Divine Planners and Human Builder in La fundación de la ciudad: mitos y ritos en el mundo antiguo. Edicions UPC. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-84-8301-387-8. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Enlil and Ninlil., Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998-.

- ^ a b Jeremy A. Black; Jeremy Black; Graham Cunningham; Eleanor Robson (13 April 2006). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. pp. 106–. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Ewa Wasilewska (2000). Creation stories of the Middle East. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-1-85302-681-2. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Robert Payne (1959). The canal builders: the story of canal engineers through the ages, p. 22. Macmillan. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Gwendolyn Leick (1998). A dictionary of ancient Near Eastern mythology. Routledge. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-0-415-19811-0. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Charles Penglase (24 March 1997). Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod. Psychology Press. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-0-415-15706-3. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Dale Launderville (1 July 2010). Celibacy in the Ancient World: Its Ideal and Practice in Pre-Hellenistic Israel, Mesopotamia, and Greece. Liturgical Press. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-8146-5697-6. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

External links

edit- Barton, George Aaron., Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions, Yale University Press, 1918. Online Version

- Cheira, Edward., Sumerian Epics and Myths, University of Chicago, Oriental Institute Publications, 1934. Online Version

- Kramer, Samuel Noah., Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C., Forgotten Books, First published 1944. Online Version

- Enlil and Ninlil., Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998-.

- Transliteration - The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998-.