Edward Arnold Chapman (16 November 1914 – 11 December 1997) was an English criminal and wartime spy. During the Second World War he offered his services to Nazi Germany as a spy and subsequently became a British double agent. His British Secret Service handlers codenamed him Agent Zigzag in acknowledgement of his erratic personal history.

Eddie Chapman | |

|---|---|

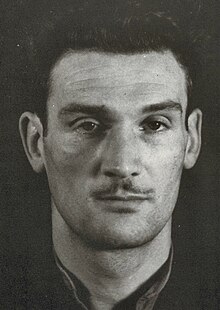

Chapman in December 1942 | |

| Born | Arnold Edward Chapman 16 November 1914 Burnopfield, County Durham, England |

| Died | 11 December 1997 (aged 83) St Albans, England |

| Spouse | Betty Farmer |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Iron Cross |

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance | |

| Agency | British Security Service (MI5) |

| Service years | 1943–1945 |

| Codename | Zigzag |

| German codename(s) | Fritz, Fritzchen |

| Operation | Damp Squib |

He had a number of criminal aliases known by the British police, amongst them Edward Edwards, Arnold Thompson and Edward Simpson. His German codename was Fritz or, later, after endearing himself to his German contacts, its diminutive form of Fritzchen.

Background

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

Chapman was born on 16 November 1914 in Burnopfield, County Durham, England. His father was a former marine engineer who ended up as a publican in Roker. The family (Chapman was the eldest of three children) had a reputation for disobedience, and Chapman received little in the way of parental guidance. Despite being bright, he regularly played truant from school to go to the cinema and hang around the beach.[1]

Aged 17, Chapman joined the Second Battalion of the Coldstream Guards, where his duties included guarding the Tower of London.[1][2] Chapman enjoyed the perks of the uniform, but soon became bored with his duties. After nine months in the army, having been granted six days of leave, he ran away with a girl he met in Soho. After two months the army caught up with him, and he was arrested and sentenced to 84 days in Aldershot military prison. On release, Chapman received a dishonourable discharge from the army.[3]

Chapman returned to Soho and spent some time working casual jobs, from barman to film extra, but his lifestyle outstripped his earnings – gambling debts and a taste for fine alcohol soon left him broke. He slipped into fraud and petty theft and, after several run-ins with the law, finally received his first civilian prison sentence, two months in Wormwood Scrubs for forging a cheque.[3] He became a safecracker with London West End gangs, spending several stretches in jail for these crimes. The gangs utilised gelignite to gain entry to safes, leading Chapman and his associates to be known as the "Jelly Gang". One of Chapman's "Jelly Gang" crimes was carried out with the help of James Wells Hunt, whom Chapman met during a stint in prison. The execution of the crime involved Chapman disguising himself as a member of the Metropolitan Water Board in order to gain access to a house in Edgware Road, from which he made his way into the shop next door by smashing through the wall. He then extracted the safe, which was transported to Hunt's Garage at 39 St Luke's Mews, where it had its door removed using gelignite.

Chapman was arrested in Scotland and charged with blowing up the safe of the headquarters of the Edinburgh Co-operative Society. Let out on bail, he fled to Jersey in the Channel Islands, where he unsuccessfully attempted to continue his criminal career. Chapman had been dining with his lover and future fiancée Betty Farmer at the Hotel de la Plage immediately before his arrest and, when he saw plain-clothes police coming to arrest him for crimes on the mainland, made a spectacular exit through the dining room window (which was shut at the time). Later that same night he committed a slapdash burglary for which he had to immediately begin serving two years in a Jersey prison, which, ironically, spared him at least 14 more years' imprisonment in a mainland prison afterwards.

Second World War

editChapman was still in prison when the Channel Islands were invaded by the Germans.[4] While incarcerated he met the petty criminal Anthony Faramus. Following a letter in German which they concocted to get off the Island, they were transferred to Fort de Romainville in Paris. There, Chapman confirmed his willingness to act as a German spy. Under the direction of Captain Stephan von Gröning, head of the Abwehr in Nantes, he was trained in explosives, radio communications, parachute jumping and other subjects in France at La Bretonnière-la-Claye, Saint-Julien-des-Landes, near Nantes, and dispatched to Britain to commit acts of sabotage.[5]

On 16 December 1942, Chapman was flown to Britain in a Focke-Wulf bomber converted for parachuting, from Le Bourget airfield.[6][7] He was equipped with wireless, pistol, cyanide capsule and £1,000 and, amongst other things, was given the task of sabotaging the de Havilland aircraft factory at Hatfield.[7] Chapman became stuck in the hatch as he tried to leave the aircraft. Finally detaching himself, he landed some distance from the target location of Mundford, Norfolk, near the village of Littleport, Cambridgeshire.[6][8]

The British secret services had been aware of Chapman's existence for some time, via Ultra (decrypted German messages), and would know his date of departure. Section B1A, the MI5-backed department with the task of capturing enemy agents and turning them into double agents, had discussed the best method of capturing Chapman without revealing Ultra. In the end, Operation Nightcap was envisioned: Rather than conduct a full-scale manhunt, planes from RAF Fighter Command would trail Chapman's aircraft to identify his landing site (from one of three possible options). Local police would then be alerted, with instructions to conduct a search under the guise of looking for a deserter.[8]

However, these plans proved unnecessary; Chapman surrendered to the local police shortly after landing and offered his services to MI5.[5] He was interrogated at Latchmere House in southwest London, better known as Camp 020. MI5 decided to use him as a double agent against the Germans and assigned Ronnie Reed as his case officer (Reed, a former BBC engineer, had been invited to join MI5 in 1940 and remained there until his retirement in 1976).[5]

Faked sabotage of de Havilland factory

editDuring the night of 29–30 January 1943, Chapman with MI5 officers faked a sabotage attack on his target, the de Havilland aircraft factory in Hatfield, where the Mosquito was being manufactured.[5][9] German reconnaissance aircraft photographed the site, and the faked damage convinced Chapman's German controllers that the attack had been successful.[10] To reinforce this story, MI5 also wrote and had published a story in the British newspaper the Daily Express.[11]

Following the de Havilland subterfuge, B1A began preparations for Chapman's return to his German handlers. Radio messages were sent to the Abwehr requesting extraction by boat or submarine, and Chapman was set to work learning a cover story ready for the inevitable interrogations. However, the response from the Abwehr was lukewarm. They refused to send a U-boat and told Chapman to return via Lisbon, Portugal. This was not a simple method, as he had no valid reason to travel to the neutral port. Reed, and other members of B1A, believed this demonstrated the Germans' reluctance to pay Chapman the £15,000 he had been promised.[12]

In the meantime Chapman was subjected to fake interrogation at Camp 020, to make sure his story held up. Reed told him to stick as close to the truth as possible, to help make the lies more realistic, and he was coached in speaking slowly to cover any hesitations. Stephens was impressed with how well Chapman responded to questioning.[12]

Portugal and Operation Damp Squib

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

MI5 was eager for Chapman to return, hoping that as a trusted asset, he could pick up significant information about the enemy. He was given the task of memorising a list of questions to which the Allies wanted answers. The list was carefully constructed so that, should Chapman be broken, its content would not show German intelligence the gaps in Allied knowledge.[13]

To get Chapman to Lisbon, it was decided he would join the crew of a merchant ship, and jump ship when it docked in Portugal. A fake identity, Hugh Anson, was constructed and the relevant paperwork was obtained before Chapman joined the crew of The City of Lancaster, sailing out of Liverpool. On making contact with Germans at their Lisbon embassy, he suggested an attempt at blowing up the ship with a bomb disguised as a lump of coal to be placed in the coal bunker. This was in response to a request from Britain's anti-sabotage section that he obtain examples of German explosive devices.

He was given two bombs, which he handed to the ship's captain. The Germans did not notice the ship was not damaged on the voyage home,[7][14] but to avoid the Germans' doubting Chapman's commitment, the British staged a conspicuous investigation of the ship when it returned to Britain, ensuring gossip would make its way back to the Germans.[15]

Chapman was sent to occupied Norway to teach at a German spy school in Oslo. After a debriefing by von Gröning, Chapman was awarded the Iron Cross for his work in apparently damaging the de Havilland works and the City of Lancaster, making him the first Englishman to receive such an award since the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71.[5] However, Nicholas Booth[16] suggests that as the Iron Cross was only ever given to military personnel, Chapman's "Iron Cross" may instead have been a War Merit Cross 2nd Class, or Kriegsverdienstkreuz.[citation needed] Chapman was inducted into the German Army as an oberleutnant or first lieutenant.[17] Chapman was also rewarded with 110,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁ and his own yacht.[18] An MI5 officer wrote in an assessment "the Germans came to love Chapman ... but although he went cynically through all the forms, he did not reciprocate. Chapman loved himself, loved adventure, and loved his country, probably in that order".[19] While in Oslo he also secretly photographed the German agents who stayed at his safe house.

Return to London

editAfter Operation Overlord he was sent back to Britain to report on the accuracy of the V-1 weapon and the Hedgehog antisubmarine weapon. He parachuted into Cambridgeshire on 29 June 1944 and went to London. Here he consistently reported to the Germans that the bombs were hitting their central London target, when in fact they were undershooting. Perhaps as a result of this disinformation, the Germans never corrected their aim, with the end result that most bombs landed in the south London suburbs or the Kent countryside, doing far less damage than they otherwise might have done.[20]

During this period he was also involved in doping of dogs in greyhound racing and was associating with criminal elements in West End nightclubs. He was also indiscreet about the sources of his income and so MI5, being unable to control him, dismissed him on 2 November 1944.[7] Chapman was given a £6,000 payment from MI5 and was allowed to keep £1,000 of the money the Germans had given him. He was granted a pardon for his pre-war activities and was reported by MI5 to have been living "in fashionable places in London always in the company of beautiful women of apparent culture".[19]

Love life

editChapman had two fiancées at the same time, each in opposite war zones. He was still betrothed to Freda Stevenson in Britain when he met Dagmar Lahlum in Norway. Stevenson was being financially assisted through MI5, and Lahlum was being treated by von Gröning.[21][failed verification] During Chapman's stay in Norway, he revealed to Dagmar that he was a British agent, but fortunately Dagmar was linked to the Norwegian resistance. She was thrilled to know that her lover was not a German officer, and they worked together to gather German information.[22]

He abandoned both women after the war and instead married his former lover Betty Farmer, whom he had left in a hurry at the Hotel de la Plage in 1938. He and Farmer later had a daughter Suzanne in 1954. Dagmar served a six-month prison sentence for consorting with an apparently German officer: thinking that Chapman was dead, she was unable to prove that he was a British agent. They met again briefly in 1994. Chapman died before he was able to redeem her name.[citation needed]

After the war

editOn his retirement, MI5 expressed some apprehension that Chapman might take up crime again when his money ran out and if caught would plead for leniency because of his highly secret wartime service. As predicted, he mixed with blackmailers and thieves and got into trouble with the police for various crimes, including smuggling gold across the Mediterranean in 1950.[23] More than once he had a character reference from former intelligence officers who confirmed his great contribution to the war effort.[24]

Chapman had his wartime memoirs serialised in France to earn money, but he was charged alongside co-defendant Wilfred Macartney under the Official Secrets Act and fined £50.[25] A few years later, when they were due to be published in the News of the World, the whole issue was pulped. However, his book The Eddie Chapman Story was eventually published in 1953.[7]

Chapman ghost-wrote the autobiography of Eric Pleasants, a British citizen who joined the Germans and served in the British Free Corps of the Waffen-SS during the war. Chapman claimed to have met Pleasants while he was imprisoned in Jersey. I Killed to Live – The Story of Eric Pleasants as Told to Eddie Chapman was published in 1957.[26] In 1967, Chapman was living in Italy and went into business as an antiquarian.[27]

Chapman and his wife later set up a health farm (Shenley Lodge, Shenley, Herts) and owned a castle in Ireland. After the war, Chapman remained friends with Baron Stephan von Gröning, his Abwehr handler (wartime alias Doctor Graumann),[21] who had fallen on hard times. Von Gröning later attended the wedding of Chapman's daughter.[7] Eddie Chapman died of heart failure on 11 December 1997. He was survived by his wife Betty, and a daughter.[7]

In popular culture

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

In the 1950s producer Ted Banborough announced plans to make a film about Chapman starring Michael Rennie or Stanley Baker, but this did not go ahead.[28]

He appeared as himself on the panel game show To Tell the Truth in November 1965.[29]

The 1966 film Triple Cross was based on the biography The Real Eddie Chapman Story[30] co-written by Chapman and Frank Owen. The film was directed by Terence Young, who had known Chapman before the war. Chapman's character was played by Christopher Plummer.[31] The film was only loosely based on reality, and Chapman was disappointed with it. In his autobiography, Plummer said that Chapman was to have been a technical adviser on the film, but the French authorities would not allow him in the country because he was still wanted over an alleged plot to kidnap the Sultan of Morocco.[32]

In 1967 French TV (ORTF) produced a short film featuring a personal à la maison interview with Chapman (in fluent French). Journalist: Pierre Dumayet, Eddie Chapman, ex-gangster, ex-espion. Serie: Cinq colonnes à la une. Producer: JP Gallo. Broadcast 6 January 1967, 19'29".[33]

In May 1989 Chapman made an extended appearance on the Channel 4 discussion programme After Dark, alongside Tony Benn, Lord Dacre, James Rusbridger, Miles Copeland and others. In 2011, BBC Two broadcast Double Agent: The Eddie Chapman Story, a Timewatch documentary presented by Ben Macintyre based on his book.[34] The book was broadcast in an abridged reading in 2012.

References

editNotes

edit- ^ a b Macintyre (2007), p. 5

- ^ Tallandier (2011), p. 23

- ^ a b Macintyre (2007), pp. 6–7

- ^ NationalArchives (28 March 1943). "KV 2 The Security Service: Personal (PF Series) Files; World War II; Double Agent Operations; KV 2/461 Edward Arnold Chapman, code-named Zigzag: British". The National Archives.

- ^ a b c d e "Eddie Chapman (Agent Zigzag)". MI5. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ a b Macintyre (2007), pp. 102–104

- ^ a b c d e f g Max Arthur, Obituary: Eddie Chapman , The Independent, 6 January 1998

- ^ a b Macintyre (2007), pp. 105–108

- ^ Obituary, telegraph.co.uk; accessed 2 August 2016.

- ^ Moran, Christopher (2013). Classified : Secrecy and the State in Modern Britain. Cambridge University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-1107000995.

- ^ "Eddie Chapman | MI5 - The Security Service". www.mi5.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ a b Macintyre (2007), pp. 176–177

- ^ Macintyre 1963, Ben (2007). Agent Zigzag : the true wartime story of Eddie Chapman : lover, betrayer, hero, spy.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ben Macintyre on a BBC TV programme 15 November 2011

- ^ Macintyre (2007) p. 222

- ^ Nicholas Booth, Zigzag – The Incredible Wartime Exploits of Double Agent Eddie Chapman, 2007, Portrait, London (ISBN 0749951567) page 224

- ^ See Macintyre, 2007, pp 231 with photo and 286.

- ^ How double agents duped the Nazis BBC 5 July 2001

- ^ a b Smith, Michael.ZigZag, a womaniser and thief who double-crossed the Nazis, The Daily Telegraph, 5 July 2001.

- ^ Nicholas Booth, Zigzag – The Incredible Wartime Exploits of Double Agent Eddie Chapman, 2007, Portrait, London (ISBN 0749951567), pp. 280–81.

- ^ a b "Edward Arnold Chapman – Agent 0747587949/ZIGZAG" (PDF). Bloomsbury Publishing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ "BBC Timewatch Eddie Chapman on Vimeo". Vimeo.com. 28 November 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ Bletchley Park Trust Museum display on Eddie Chapman

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (20 December 1997). "Eddie Chapman, 83, Safecracker and Spy". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ^ "Secrets Case Heard In Camera". The Times. 30 March 1946. p. 2.

- ^ I Killed To Live - the Story of Eric Pleasants as Told to Eddie Chapman Cassell & Company Ltd. 1957.

- ^ Pierre Dumayet (Journalist: Pierre Dumayet, Eddie Chapman, ex-gangster, ex-espion. Serie: Cinq colonnes à la une. Producer.: JP Gallo. Broadcast 6 January 1967,) Eddie Chapman, ex-gangster, ex-espion. Producer: J-P Gallo. 6 January 1967.

- ^ "Eddie Chapman may visit Sydney: Movie Plans For Ex-spy". The Sun-Herald (Sydney, NSW: 1953–1954). Sydney, NSW: National Library of Australia. 7 November 1954. p. 21. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Chapman, Bruce and Pemminger". To Tell the Truth. 8 November 1965. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ Macintyre (2007 revised 2010) p318

- ^ Triple Cross at IMDb

- ^ Plummer, Christopher In Spite of Myself: A Memoir 2008 Knopf

- ^ INA has released the video on its official Youtube site.["Eddie Chapman, ex-gangster, ex-espion" (in French). Ina.fr. Retrieved 3 December 2021.]

- ^ Macintyre, Ben (2011). "Double Agent: The Eddie Chapman Story". Walkergeorgefilms.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

Bibliography

edit- Edward Chapman and Frank Owen The Eddie Chapman Story, Pub: Messner, New York City, 1953 (ASIN B0000CIO9B)

- Booth, Nicholas (2007) Zigzag – The Incredible Wartime Exploits of Double Agent Eddie Chapman. London: Portrait ISBN 0749951567

- Macintyre, Ben (2007). Agent Zigzag: The True Wartime Story of Eddie Chapman, Lover, Betrayer, Hero, Spy. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-7475-8794-1.

- Reed, Nicholas (2011). My Father, the Man Who Never Was: Ronnie Reed, The Life and Times of an MI5 Officer, pp. 60–92. Folkestone: Lilburne Press. ISBN 978-1-901167-21-4.

- Tallandier, Ed (2011). Eddie Chapman, Ma Fantastique histoire. Texto. ISBN 978-2-84734-822-4.

- Masterman, John Cecil (2013) [1972, Yale University]. The Double-Cross System. London: Vintage, Random House. ISBN 9780099578239.

- Chapman, Betty; Bonewitz, Dr. Ronald L. (2013). Mrs Zigzag: The Extraordinary Life of a Secret Agent's Wife. London: The History Press. ISBN 9780752488134.

External links

edit- WHERE THE RABBIT IS LIKELY TO PASS US Defence Intelligence Agency uses Eddie Chapman case as an example] by A Denis Clift, President Joint Military Intelligence College Harvard University 15 January 2002

- Obituary Eddie Chapman – The Telegraph 1997

- Double Agent: The Eddie Chapman Story at bbc.co.uk, first broadcast 15 November 2011