The red-cockaded woodpecker (Leuconotopicus borealis) is a woodpecker endemic to the southeastern United States.[5][6] It is a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973.[7][8]

| Red-cockaded woodpecker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female with insect prey in mouth | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Piciformes |

| Family: | Picidae |

| Genus: | Leuconotopicus |

| Species: | L. borealis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Leuconotopicus borealis (Vieillot, 1809)

| |

| |

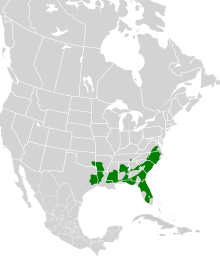

| Current range[3] | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

Description

editThe red-cockaded woodpecker is small- to mid-sized species, being intermediate in size between North America's two most widespread woodpeckers (the downy and hairy woodpeckers). This species measures 18–23 cm (7.1–9.1 in) in length, spans 34–41 cm (13–16 in) across the wings and weighs 40–56 g (1.4–2.0 oz).[6][9][10] Among the standard measurements, the wing chord is 9.5–12.6 cm (3.7–5.0 in), the tail is 7–8.2 cm (2.8–3.2 in), the bill is 1.9–2.3 cm (0.75–0.91 in) and the tarsus is 1.8–2.2 cm (0.71–0.87 in).[11] Its back is barred with black and white horizontal stripes. The red-cockaded woodpecker's most distinguishing feature is a black cap and nape that encircle large white cheek patches. Rarely visible, except perhaps during the breeding season and periods of territorial defense, the male has a small red streak on each side of its black cap called a cockade, hence its name. The species is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN[1] and as Threatened by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.[12][13]

Behavior

editThe red-cockaded woodpecker feeds primarily on ants, beetles, cockroaches, caterpillars, wood-boring insects, and spiders, and occasionally fruit and berries. The vast majority of foraging is on pines, with a strong preference for large trees, though they will occasionally forage on hardwoods and even on corn earworms in cornfields.[14]

Red-cockaded woodpeckers are a territorial, nonmigratory, cooperative breeding species, frequently having the same mate for several years. The nesting season runs from April to June. The breeding female lays three to four eggs in the breeding male's roost cavity. Group members incubate the small white eggs for 10–13 days. Once hatched, the nestlings remain in the nest cavity for about 26–29 days. Upon fledging, the young often remain with the parents, forming groups of up to nine or more members, but more typically three to four members. There is only one pair of breeding birds within each group, and they normally only raise a single brood each year. The other group members, called helpers, usually males from the previous breeding season, help incubate the eggs and raise the young. Juvenile females generally leave the group before the next breeding season, in search of solitary male groups. The main predators of red-cockaded nests are rat snakes, although corn snakes also represent a threat.[15] Studies have also explored the possibility that southern flying squirrels might have a negative impact on red-cockaded woodpecker populations due competition over cavities and predation on eggs and nestlings. [16]

Distribution and habitat

editHistorically, this woodpecker's range extended in the southeastern United States from Florida to New Jersey and Maryland, as far west as eastern Texas and Oklahoma, and inland to Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Today it is estimated that there are about 5,000 groups of red-cockaded woodpeckers, or 12,500 birds, from Florida to Virginia and west to southeast Oklahoma and eastern Texas, representing about one percent of the woodpecker's original population (over 1 million individuals at one point). They have become locally extinct (extirpated) in Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, New Jersey, and Tennessee.[17]

The red-cockaded woodpecker makes its home in fire-dependent pine savannas.[17] Longleaf pines (Pinus palustris) are most commonly preferred, but other species of southern pine are also acceptable. While other woodpeckers bore out cavities in dead trees where the wood is rotten and soft, the red-cockaded woodpecker is the only one that excavates cavities exclusively in living pine trees. The older pines favored by the red-cockaded woodpecker often suffer from a fungal infection called red heart rot which attacks the center of the trunk, causing the inner wood, the heartwood, to become soft. Cavities are generally excavated over 1 to 3 years.

The aggregate of cavity trees is called a cluster and may include 1 to 20 or more cavity trees on 3 to 60 acres (12,000 to 240,000 m2). The average cluster is about 10 acres (40,000 m2). Cavity trees that are being actively used have numerous, small resin wells which exude sap. The birds keep the sap flowing apparently as a cavity defense mechanism against rat snakes and possibly other predators. The typical territory for a group ranges from about 125 to 200 acres (500,000 to 800,000 m2), but observers have reported territories running from a low of around 60 acres (240,000 m2), to an upper extreme of more than 600 acres (2.40 km2). The size of a particular territory is related to both habitat suitability and population density. Where red-cockaded woodpeckers occur at high densities, individuals appear to spend more time in territorial defense, potentially at the expense of foraging and time allocated to reproduction, resulting in reduced clutch size and fledgling production.[18]

Ecology

editThe red-cockaded woodpecker is a keystone species in southern pine forest ecosystems.[19] Their cavities are used secondarily by at least 27 species of vertebrates, including small birds (e.g., eastern bluebirds, tufted titmouse, and great crested flycatcher),[19][20] mammals (e.g., evening bat),[20] herpetofauna (e.g., broad-headed skinks, gray treefrogs),[16] and invertebrates (e.g., wasps, bees, moths, and ants).[16]

Pileated woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus), often enlarge cavities created by red-cockaded woodpeckers, making the tree uninhabitable to the red-cockaded woodpecker, but providing habitat for larger birds like eastern screech owls, wood ducks, and American kestrels.[21][16] Smaller animals, like the red-bellied woodpecker, red-headed woodpecker, and southern flying squirrel may compete with red-cockaded woodpeckers for unenlarged nests.[16]

Conservation

editThe red-cockaded woodpecker suffers from habitat fragmentation when habitable pines are removed. When a larger cluster of birds gets split up, it is difficult for the young to find mates and eventually becomes an issue regarding species dispersal.[22] While dispersing in search of new places to settle, the red-cockaded woodpecker encounters habitats of competing woodpecker species.

The red-cockaded woodpecker has been the focus of conservation efforts even before the passing of the Endangered Species Act in 1973. In Florida, pairs are being released at DuPuis Management Area and other privately-owned land.

Due to the high importance of nesting habitat on the woodpecker's reproduction, much management has been dedicated to create ideal and more numerous nesting sites. Nesting clusters have been spared from forestry activity to preserve old-growth, large diameter trees. The nesting sites themselves have also been managed to make them more appealing. The use of controlled burning has been used to reduce deciduous growth around nesting colonies. The red-cockaded woodpecker has been shown to prefer nesting sites with less deciduous growth. The use of controlled burning must be exercised with caution due to the highly flammable resin barriers formed by the woodpecker.[23]

In an effort to increase the red-cockaded woodpecker population, states such as Texas, Louisiana, Alabama, and Georgia's wildlife management are creating artificial cavities in Longleaf Pine trees. There are two methods in which wildlife management officers use to insert cavities in long leaf pines. The most respected and latest approach is to carve out a nesting cavity in the tree and insert a man-made rot-resistant wooden box with a PVC pipe small enough for only a red-cockaded woodpecker to fit through. These boxes, also known as "inserts", can last up to 10 years. The older and less used approach is to drill a cavity into the tree in hopes that the birds will settle there and nest.[24]

Due to the energetically expensive process of excavating new cavities, more energy is expended competing for existing home ranges rather than colonizing new areas. Cavities are highly sought-out resources by all cavity dwelling species and red-cockadeds have been observed roosting in them as early as the same night the boxes are installed. Alpha males usually reside in the best cavity, alpha females in the second best cavity until breeding season when their male partners allow their cavity to turn into the nest cavity. Juveniles are left with the lower quality cavities or no cavities at all, forcing them to roost on a branch outside overnight. Due to the fact that each family member requires a cavity to roost, land managers may choose to insert additional artificial cavities to boost survival of juveniles. Red-cockaded woodpeckers will even recolonize abandoned ranges when cavities are created.[25]

In addition to the creation of new cavities, methods for protecting existing cavities are also used. The most common technique employed is a restrictor plate. The plate prevents other species from enlarging or changing the shape of the cavity entrance. These restrictor plates must be carefully monitored, however, to ensure that no hindrance is given to the woodpecker. Adjustments must also be made as the tree grows.[26] Southern flying squirrel exclusion devices may be considered as well. [27] A study suggested that managers establish new woodpecker clusters away from streams and limit the use of excess cavities, both factors important in the recruitment of flying squirrels.[28] Application of capsaicin on flying squirrel at cavities could be a cost-effective method.[29]

Intentional habitat destruction by landowners

editPrivate landowners are prohibited from modifying habitats or taking animals that are protected by the Endangered Species Act (ESA). In response to the listing of the red-cockaded woodpecker, it became common in Eastern Texas for landowners to begin cutting down the long-leaf pine trees so that the woodpeckers would not nest in their trees.[22][30] By eliminating the trees on a piece of privately owned land, the land owners no longer have to abide by the requirements of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists. By removing available habitat for the species, landowners are able to benefit economically and maintain construction rights to the property.[31] This led to the development of the Safe Harbor Agreements in which landowners agreed to manage their land in consistency with the conservation of a species of special conservation concern in return for relaxed ESA protection rules that allow a more flexible management of their own land.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International (2020). "Leuconotopicus borealis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22681158A179376787. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22681158A179376787.en. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ NatureServe (3 March 2023). "Dryobates borealis". NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Red-cockaded Woodpecker Range Map". All About Birds, TheCornellLab of Ornithology. Cornell University. 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Leuconotopicus borealis (Vieillot, 1809)". Catalogue of Life. Species 2000: Leiden, the Netherlands. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "species: Dryobates borealis (Red-cockaded Woodpecker, Pic à face blanche)". AOS Checklist of North and Middle American Birds. American Ornithological Society. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ a b Pool, Nathan (2014). Powers, Karen; Siciliano Martina, Leila (eds.). "Picoides borealis". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Red-cockaded woodpecker (Picoides borealis)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ 35 FR 16047

- ^ "Red-Cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides borealis)". fact-sheets.com. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15.

- ^ "Red-cockaded Woodpecker: Life History". All About Birds, TheCornellLab of Ornithology. Cornell University. 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Woodpeckers: An Identification Guide to the Woodpeckers of the World by Hans Winkler, David A. Christie & David Nurney. Houghton Mifflin (1995), ISBN 978-0395720431

- ^ "Red-cockaded woodpecker (Picoides borealis)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ 35 FR 16047

- ^ Jackson, J. A. (1994). Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Dryobates borealis), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.85

- ^ Longleaf Alliance Archived 2013-11-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Conner, Richard N.; Rudolph, D. Craig; Saenz, Daniel; Schaefer, Richard R. 1996. Red-cockaded woodpecker nesting success, forest structure, and southern flying squirrels in Texas. Wilson Bulletin. 108(4): 697-711.

- ^ a b "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Red-cockaded Woodpecker". Archived from the original on 2021-03-18. Retrieved 2017-03-19.

- ^ Garabedian, J.E.; Moorman, C.E.; Peterson, M.N.; Kilgo, J.C. (2018). "Evaluating interactions between space‐use sharing and defence under increasing density conditions for the group‐territorial Red‐cockaded Woodpecker Leuconotopicus borealis". Ibis. 160 (4): 816–831. doi:10.1111/ibi.12576.

- ^ a b "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Red-cockaded Woodpecker". Archived from the original on 2021-03-18. Retrieved 2017-03-19.

- ^ a b Rudolph, D. Craig; Conner, Richard N.; Turner, Janet (1990). "Competition for Red-Cockaded Woodpecker Roost and Nest Cavities: Effects of Resin Age and Entrance Diameter". The Wilson Bulletin. 102 (1): 23–36.

- ^ Saenz, Daniel; Conner, Richard N.; Shackelford, Clifford E.; Rudolph, Craig D. (1998). The Wilson Bulletin. Vol. 110. Wilson Ornithological Society. pp. 362–367. JSTOR 4163960.

- ^ a b Conner, Richard N.; Rudolph, D. Craig (1991). "Forest Habitat Loss, Fragmentation, and Red-Cockaded Woodpecker Populations". The Wilson Bulletin. 103 (3). Wilson Ornithological Society: 446–457. JSTOR 4163048.

- ^ Richard N. Conner; Brian A. Locke (Winter 1979). "Effects of a Prescribed Burn on Cavity Trees of Red-Cockaded Woodpeckers". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 7 (4): 291–293. JSTOR 3781867.

- ^ Georgia Public Broadcasting: Georgia Outdoors. "The Red Hills of Georgia (transcript, p. 6)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-28. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ^ Carole K. Copeyon; Jeffrey R. Walters; J. H. Carter III (Oct 1991). "Induction of Red-Cockaded Woodpecker Group Formation by Artificial Cavity Construction". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 55 (4): 549–556. doi:10.2307/3809497. JSTOR 3809497.

- ^ J.H. Carter, III; Jeffrey R. Walters; Steven H. Everhart; Phillip D. Doerr (Spring 1989). "Restrictors for Red-Cockaded Woodpecker Cavities". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 17 (1): 68–72. JSTOR 3782042.

- ^ Loeb, Susan C. (1996). "Effectiveness of flying squirrel excluder devices on red-cockaded woodpecker cavities". Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. 50: 303–311. Retrieved 21 March 2023 – via Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.

- ^ Martin, Emily J.; Gigliotti, Franco N.; Ferguson, Paige F.B. (2021). "Synthesis of Red-cockaded Woodpecker management strategies and suggestions for regional specificity in future management". Ornithological Applications. 123 (3). doi:10.1093/ornithapp/duab031. duab031.

- ^ Meyer, Robert; Cox, Jim (2019). "Capsaicin as a tool for repelling southern flying squirrels from red-cockaded woodpecker cavities". Human–Wildlife Interactions. 13 (1): 79–86. ISSN 2155-3874. Retrieved 21 March 2023 – via UtahStateLibrary.

- ^ Burnett, H. Sterling (13 July 2017). "Endangered Species Act Doesn't Save Species". The Heartland Institute. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ Stroup, Richard L. (1 April 1995). Shaw, Jane S. (ed.). "The Endangered Species Act: Making Innocent Species the Enemy". Property and Environment Research Center. Issue Number PS-3. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

Further reading

edit- "Red-cockaded woodpecker". US Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 2004-04-06.

- "Red-cockaded Woodpecker US Distribution". eBird.

External links

edit- BirdLife Species Factsheet.

- The Nature Conservancy's Species page: Red Cockaded woodpecker

- Red-cockaded woodpecker photo gallery VIREO*Red-cockaded woodpecker videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- A little bit more about the red-cockaded woodpecker and a few other endangered birds

- Ecos.fws.gov, Species Profile

- W.G.Jones State Forest, Conroe, TX