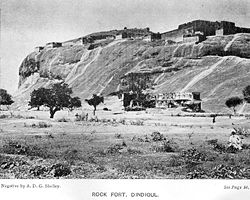

The Dindigul Fort or Dindigul Malai Kottai and Abirami amman Kalaheswarar Temple was built in 16th-century by Madurai Nayakar Dynasty situated in the town of Dindigul in the state of Tamil Nadu in India. The fort was built by the Madurai Nayakar king Muthu Krishnappa Nayakar in 1605. In the 18th century the fort passed on to Kingdom of Mysore (Mysore Wodeyars). Later it was occupied by Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan the fort was of strategic importance. In 1799 it went to the control of the British East India Company during the Polygar Wars. There is an abandoned temple on its peak apart from few cannons sealed with balls inside.These canons are very heavy. In modern times, the fort is maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India and is open to tourists.

| Dindigul Rock Fort | |

|---|---|

| Part of History of Tamil Nadu | |

| Dindigul | |

Dindigul in 1913 | |

| Coordinates | 10°21′40″N 77°57′42″E / 10.36109°N 77.96167°E |

| Type | Rock fort and temple complex |

| Height | 900 feet |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Archaeological Survey of India |

| Controlled by | Archaeological Survey of India |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Under renovation |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1605 |

| Built by | Muthu Krishnappa Nayakkar |

| In use | circa early 1800s |

| Materials | Granite |

Etymology

editDindigul city derives its name from a portmanteau of Thindu a Tamil word which means a ledge or a headrest attached to ground and kal another Tamil word which means Rock. Appar, the Saiva poet visited the city and noted it in his works in Tevaram. Dindigul finds mention in the book Padmagiri Nadhar Thenral Vidu thudhu written by the poet Palupatai sokkanathar as Padmagiri. This was later stated by U. V. Swaminatha Iyer (1855–1942) in his foreword to the above book. He also mentions that Dindigul was originally called Dindeecharam.[1]

History

editEarly Dindigul history

editThe history of Dindigul is centered on the fort over the small rock hill and fort. Dindigul region was the border of the three prominent kingdoms of South India, the Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas. During the first century A.D., the Chola king Karikal Cholan captured the Pandya kingdom and Dindigul came under the Chola rule. During the sixth century, the Pallavas took over most provinces of Southern India and Dindigul was under the rule of Pallavas until Cholas regained the state in the 9th century and the Pandyas regained control by the 13th century.

In the 14th century, half of Tamil Nadu kingdoms were under the short-reigned Delhi Sultanates with Madurai Sultanate ruling this region between 1335–1378. By end of 1378, the Muslim rulers were defeated by the Vijayanagara army who later established their rule.

Madurai Nayaks

editIn 1559 Madurai Nayaks, till then part of Vijayanagara empire became powerful and with Dindigul became a strategic gateway to their kingdom from North . After the death of King Viswanatha Nayak in 1563, Muthukrisna Nayakka became the king of kingdom in 1602 A.D who built the strong hill fort in 1605 A.D. He also built a fort at the bottom of the hill. Muthuveerappa Nayak and Thirumalai Nayak followed Muthukrishna Nayak. Dindigul came to prominence once again during Nayaks rule of Madurai under Thirumalai Nayak. After his immediate unsuccessful successors, Rani Mangammal became the ruler of the region who ruled efficiently.[1]

Under Mysore Rayas and Hyder Ali

editIn 1742, the Mysore army under the leadership of Venkata Raya conquered Dindigul. He governed Dindigul as a representative of Maharaja of Mysore. There were Eighteen Palayams (a small region consists of few villages) during his reign and all these palayams were under Dindigul Semai with Dindiguls capital. These palayams wanted to be independent and refused to pay taxes to venkatarayer.[1][2] In 1748, Venkatappa was made governor of the region in place of Venkatarayer, who also failed. In 1755, Mysore Maharaja sent Haider Ali to Dindigul to handle the situation. Later Haider Ali became the de facto ruler of Mysore and in 1777, he appointed Purshana Mirsaheb as governor of Dindigul. He strengthened the fort. His wife Ameer-um-Nisha-Begam died during her delivery and her tomb is now called Begambur. In 1783 British army, led by captain long invaded Dindigul. In 1784, after an agreement between the Mysore Kingdom and British army, Dindigul was restored by Mysore Kingdom. In 1788, Tipu Sultan, the Son of Haider Ali, was crowned as King of Dindigul.[1][3][4][5]

Under British

editIn 1790, James Stewart of the British army gained control over Dindigul by invading it in the second war of Mysore. In a pact made in 1792, Tipu ceded Dindigul along with the fort to the English. Dindigul is the first region to come under English rule in the Madurai District. In 1798, the British army strengthened the hill fort with cannons and built sentinel rooms in every corner. The British army, under statten stayed at Dindigul fort from 1798 to 1859. After that Madurai was made headquarters of the British army and Dindigul was attached to it as a taluk. Dindigul was under the rule of the British Until India got our Independence on 15 August 1947.[1][3]

The fort played a major role during the Polygar wars, between the Palayakarars, Tipu Sultan duo aided by the French against the British, during the last decades of the 18th century. The polygar of Virupachi, Gopal Nayak commanded the Dindugal division of Polygars, and during the wars aided the Sivaganga queen Queen Velu Nachiyar and her commanders Maruthu Pandiyar Brothers to stay the fort after permission from Hyder Ali.[6]

Architecture

editThe rock fort is 900 ft (270 m) tall and has a circumference of 2.75 km (1.71 mi). Cannon and gunfire artillery were included in the fort during the 17th century. The fort was cemented with double walls to withstand heavy artillery. Cannons were installed at vantage points around the fort with an arms and ammunition godown built with safety measures. The double-walled rooms were fully protected against external threat and were well ventilated by round ventilation holes in the roof. A thin brick wall in one corner of the godown helped soldiers escape in case of emergency. The sloping ceiling of the godown prevented seepage of rainwater. The fort has 48 rooms that were once used as cells to lodge war prisoners and slaves, a spacious kitchen, a horse stable and a meeting hall for the army commanders. The fort also has its own rainwater reservoirs constructed by taking advantage of the steep gradient. The construction highlights the ingenuity of Indian kings in their military architecture.[7][8]

Maintenance

editThe fort is maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India and maintains it as a protected monument. An entry fee of ₹25 is charged for Indian citizens and ₹300 for foreigners. The fort receives few visitors in college and school students and the occasional foreign tourists. Visitors are allowed to walk around the tunnels and trenches that reveals the safety features of the structure. The temple has some sculptures and carvings, with untarnished rock cuts.

Visitors can view the ruins within the fort walls, arsenal depots, or animal stables) and damaged halls decorated with carved stone columns. Visitors are allowed to go up to the cannon point and look through the spy holes. The top of the fort also offers a scenic view of Dindigul on the eastern side and villages and farmland on the other sides. Lack of funds and facilities has kept the fort misused by nearby dwellers. But in 2005, Keeranur-based ASI in Pudukkottai district fenced the entire surroundings and refurbished some of the dilapidated structures.[7][9][10]

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d e "Historical moments". Dindigul municipality. 2011. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Nelson 1989, p. 258

- ^ a b Nelson 1989, pp. 286-93

- ^ Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). History of Tipu Sultan. Aakar Books. pp. 68–69. ISBN 81-87879-57-2.

- ^ Beveridge, Henry (1867). A comprehensive history of India, civil, military and social, from the first landing of the English, to the suppression of the Sepoy revolt:including an outline of the early history of Hindoostan, Volume 2. Blackie and son. pp. 222–24.

- ^ "Gopal Naicker Memorial ready for inauguration". The Hindu. Palani. 22 June 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ a b Basu, Soma (2 April 2005). "Pillow Rock". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 June 2006. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "Cannonballs unearthed from Dindigul fort". The Hindu. 2 March 2004. Archived from the original on 24 June 2004. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "Alphabetical List of Monuments - Tamil Nadu". Archaeological Survey of India. 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "List of ticketed monuments - Tamil Nadu". Archaeological Survey of India. 2011. Archived from the original on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

References

edit- Nelson, James Henry (1989). The Madura Country: A Manual. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120604247.